This video provided by the University of Chicago features interviews about the evolution of teeth with paper lead author Yara Haridy and co-author Neil Shubin.

- Teeth evolved from sensory structures on the exoskeleton of ancient jawless fish that lived 465 million years ago.

- Similar sensory structures also evolved in ancient invertebrates that lived 485 to 540 million years ago.

- These sensory structures evolved independently in invertebrates and vertebrates to take advantage of the same environmental conditions in the water.

Teeth-like sensory structures appeared hundreds of millions of years ago

Teeth are sensitive. Biting into an ice cube can send a cold shock through your jaw. It hurts when a dentist drills into your tooth. That’s because the inner layer of a tooth, called the dentine, transmits information to nerves at the center of the tooth, called the pulp. On May 23, 2025, scientists at the University of Chicago said we can blame it on jawless fish that lived 465 million years ago. They said our teeth evolved from sensory tissue on the exoskeleton of ancient, armored fish. In addition, they found similar sensory structures on invertebrates that lived even earlier, 485 to 540 million years ago. Their study shows these sensory structures evolved independently in vertebrates and invertebrates.

When the paper’s lead author, Yara Haridy, started investigating fossils from the Cambrian Period (485 to 540 million years ago), she was looking for the earliest vertebrates in the fossil record. The Cambrian was a notable time in the history of life on Earth because it had a high diversity of animal species. Her investigation led her down a path into the evolution of teeth.

Haridy borrowed fossils from several museums and took them to the Argonne National Laboratory to obtain high resolution micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) scans. She and her colleagues then studied the CT scans of the ancient fossils and some related living animals.

The researchers published their study in the peer-reviewed journal Nature on May 21, 2025.

Sensory tissues evolved to become teeth

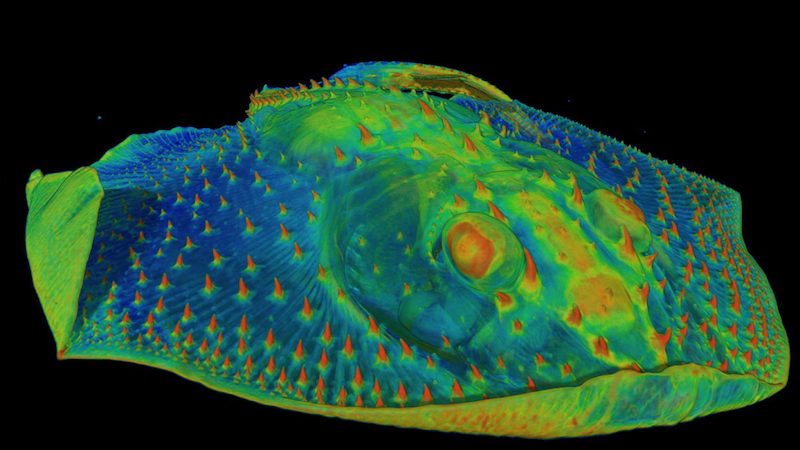

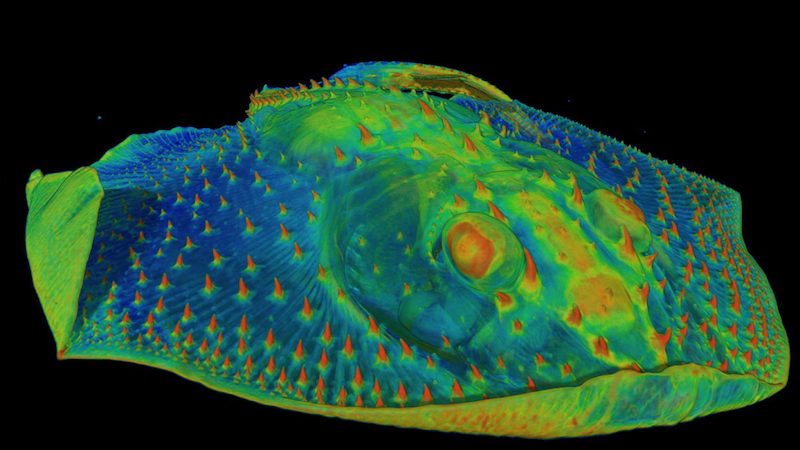

Odontodes are bumps on the exoskeleton of ancient, armored fish. Scientists have long suspected that teeth evolved from odontodes. However, they did not know the purpose of those structures. Now, detailed CT imaging shows that internal structures in an ancient fish called Eriptychius contained dentine. Therefore, these odontodes acted like a sensory organ to help the fish sense its watery environment.

Today, some fish – such as sharks, skates and catfish – have tooth-like structures called denticles, instead of scales, on their skin. In the lab, Haridy and her team studied the tissues of suckermouth catfish, sharks and skates. When she examined their skin tissues, she could see the denticles — the tooth-like structures — were connected to nerves. It was similar to the odontodes found on ancient, armored fish.

But how did structures like odontodes, those bumps on the exoskeleton, become teeth in vertebrates? One hypothesis is that the teeth-like structures appeared first and were eventually adapted to exoskeletons. But the scientists sid their analysis supports another hypothesis. These structures developed on the exoskeleton and later evolved to become sensitive teeth. As the jawless fish evolved to have a jaw, there was an advantage to having sharp implements in its mouth to grab prey. Therefore, the odontodes evolved to become teeth. And as evolution progressed, ancient fish with jaws and teeth emerged from the water to become land animals.

Searching for odontodes earlier in time

There was one fossil the scientists were particularly interested in: Anatolepis. It was a creature from the Cambrian Period that had previously been identified as a vertebrate. The detailed CT scans showed signs of pores inside the odontodes (bumps on the exoskeleton) that were filled with material that appeared to be dentine.

It was an exciting find. Haridy said:

We were high fiving each other, like ‘oh my god, we finally did it.’ That would have been the very first tooth-like structure in vertebrate tissues from the Cambrian. So, we were pretty excited when we saw the telltale signs of what looked like dentine.

But was Anatolepis really a Cambrian vertebrate? The scientists compared structures found in Anatolepis with detailed scans of other fossils and extant animals. To their surprise, the analysis revealed that Anatolepis was actually an invertebrate, not a vertebrate. Its dentine-like pores in the odontodes more closely resembled sensory organs found on the shells of invertebrates such as crabs and shrimp.

Haridy remarked:

This shows us that ‘teeth’ can also be sensory even when they’re not in the mouth. So, there’s sensitive armor in these fish. There’s sensitive armor in these arthropods [invertebrates with an exoskeleton]. This explains the confusion with these early Cambrian animals. People thought that this was the earliest vertebrate, but it actually was an arthropod.

Teeth-like sensory organs evolved separately

Some invertebrate fossils from the Cambrian Period had teeth-like structures. And these structures bore some resemblance to those in the vertebrate fossil armored fish exoskeleton. Furthermore, they also resembled sensory organs in the shells of creatures like extant crabs and shrimp. Both the similarities and differences suggest that sensory organs in the exoskeleton evolved independently in vertebrates and invertebrates. Why did this happen? It was all about the environment they were living in.

Co-author Neil Shubin of the University of Chicago explained:

When you think about an early animal like this, swimming around with armor on it, it needs to sense the world. This was a pretty intense predatory environment and being able to sense the properties of the water around them would have been very important. So, here we see that invertebrates with armor like horseshoe crabs need to sense the world too, and it just so happens they hit on the same solution.

Bottom line: Our teeth evolved from sensory tissue on the exoskeleton of an ancient, armored fish that lived 465 million years ago. Similar sensory structures also arose independently on the bodies of invertebrates that lived even earlier, 485 to 540 million years ago.

Source: The origin of vertebrate teeth and evolution of sensory exoskeletons

Read more: Ancient 4-limbed fish reveals origin of human hand

The post Our teeth have strange origins in ancient fish first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/0NERlxU

This video provided by the University of Chicago features interviews about the evolution of teeth with paper lead author Yara Haridy and co-author Neil Shubin.

- Teeth evolved from sensory structures on the exoskeleton of ancient jawless fish that lived 465 million years ago.

- Similar sensory structures also evolved in ancient invertebrates that lived 485 to 540 million years ago.

- These sensory structures evolved independently in invertebrates and vertebrates to take advantage of the same environmental conditions in the water.

Teeth-like sensory structures appeared hundreds of millions of years ago

Teeth are sensitive. Biting into an ice cube can send a cold shock through your jaw. It hurts when a dentist drills into your tooth. That’s because the inner layer of a tooth, called the dentine, transmits information to nerves at the center of the tooth, called the pulp. On May 23, 2025, scientists at the University of Chicago said we can blame it on jawless fish that lived 465 million years ago. They said our teeth evolved from sensory tissue on the exoskeleton of ancient, armored fish. In addition, they found similar sensory structures on invertebrates that lived even earlier, 485 to 540 million years ago. Their study shows these sensory structures evolved independently in vertebrates and invertebrates.

When the paper’s lead author, Yara Haridy, started investigating fossils from the Cambrian Period (485 to 540 million years ago), she was looking for the earliest vertebrates in the fossil record. The Cambrian was a notable time in the history of life on Earth because it had a high diversity of animal species. Her investigation led her down a path into the evolution of teeth.

Haridy borrowed fossils from several museums and took them to the Argonne National Laboratory to obtain high resolution micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) scans. She and her colleagues then studied the CT scans of the ancient fossils and some related living animals.

The researchers published their study in the peer-reviewed journal Nature on May 21, 2025.

Sensory tissues evolved to become teeth

Odontodes are bumps on the exoskeleton of ancient, armored fish. Scientists have long suspected that teeth evolved from odontodes. However, they did not know the purpose of those structures. Now, detailed CT imaging shows that internal structures in an ancient fish called Eriptychius contained dentine. Therefore, these odontodes acted like a sensory organ to help the fish sense its watery environment.

Today, some fish – such as sharks, skates and catfish – have tooth-like structures called denticles, instead of scales, on their skin. In the lab, Haridy and her team studied the tissues of suckermouth catfish, sharks and skates. When she examined their skin tissues, she could see the denticles — the tooth-like structures — were connected to nerves. It was similar to the odontodes found on ancient, armored fish.

But how did structures like odontodes, those bumps on the exoskeleton, become teeth in vertebrates? One hypothesis is that the teeth-like structures appeared first and were eventually adapted to exoskeletons. But the scientists sid their analysis supports another hypothesis. These structures developed on the exoskeleton and later evolved to become sensitive teeth. As the jawless fish evolved to have a jaw, there was an advantage to having sharp implements in its mouth to grab prey. Therefore, the odontodes evolved to become teeth. And as evolution progressed, ancient fish with jaws and teeth emerged from the water to become land animals.

Searching for odontodes earlier in time

There was one fossil the scientists were particularly interested in: Anatolepis. It was a creature from the Cambrian Period that had previously been identified as a vertebrate. The detailed CT scans showed signs of pores inside the odontodes (bumps on the exoskeleton) that were filled with material that appeared to be dentine.

It was an exciting find. Haridy said:

We were high fiving each other, like ‘oh my god, we finally did it.’ That would have been the very first tooth-like structure in vertebrate tissues from the Cambrian. So, we were pretty excited when we saw the telltale signs of what looked like dentine.

But was Anatolepis really a Cambrian vertebrate? The scientists compared structures found in Anatolepis with detailed scans of other fossils and extant animals. To their surprise, the analysis revealed that Anatolepis was actually an invertebrate, not a vertebrate. Its dentine-like pores in the odontodes more closely resembled sensory organs found on the shells of invertebrates such as crabs and shrimp.

Haridy remarked:

This shows us that ‘teeth’ can also be sensory even when they’re not in the mouth. So, there’s sensitive armor in these fish. There’s sensitive armor in these arthropods [invertebrates with an exoskeleton]. This explains the confusion with these early Cambrian animals. People thought that this was the earliest vertebrate, but it actually was an arthropod.

Teeth-like sensory organs evolved separately

Some invertebrate fossils from the Cambrian Period had teeth-like structures. And these structures bore some resemblance to those in the vertebrate fossil armored fish exoskeleton. Furthermore, they also resembled sensory organs in the shells of creatures like extant crabs and shrimp. Both the similarities and differences suggest that sensory organs in the exoskeleton evolved independently in vertebrates and invertebrates. Why did this happen? It was all about the environment they were living in.

Co-author Neil Shubin of the University of Chicago explained:

When you think about an early animal like this, swimming around with armor on it, it needs to sense the world. This was a pretty intense predatory environment and being able to sense the properties of the water around them would have been very important. So, here we see that invertebrates with armor like horseshoe crabs need to sense the world too, and it just so happens they hit on the same solution.

Bottom line: Our teeth evolved from sensory tissue on the exoskeleton of an ancient, armored fish that lived 465 million years ago. Similar sensory structures also arose independently on the bodies of invertebrates that lived even earlier, 485 to 540 million years ago.

Source: The origin of vertebrate teeth and evolution of sensory exoskeletons

Read more: Ancient 4-limbed fish reveals origin of human hand

The post Our teeth have strange origins in ancient fish first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/0NERlxU

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire