A supernova explodes

The Crab nebula is a supernova remnant. It’s what’s left of an exploded star. A vast expanding cloud of gas and dust surrounding one of the densest objects in the universe, a neutron star.

Chinese astronomers noticed the sudden appearance of a star blazing in the daytime sky on July 4, 1054 CE. It likely outshone the brightest planet, Venus, and was temporarily the 3rd-brightest object in the sky, after the sun and moon. This “guest star” – the exploding supernova – remained visible in daylight for some 23 days. At night it shone near Tianguan – a star we now call Zeta Tauri, in the constellation Taurus the Bull – for nearly two years. Then it faded from view.

The supernova erupted – and the Crab nebula formed – about 6,500 light-years away.

The Crab nebula and supernova in history

The ancestral Puebloan people in the American Southwest may have viewed the bright new star in 1054. A crescent moon was in the sky near the new star on the morning of July 5, the day following the observations by the Chinese. So the pictograph below, from Chaco Canyon in New Mexico, might depict the event. The multi-spiked star to the left represents the supernova near the crescent moon. Furthermore, the handprint above may signify the importance of the event or may be the artist’s signature.

After exploding onto the scene in 1054 and shining brightly for two years, there are no reports of anything unusual in this spot in the sky until 1731. Then in that year, English amateur astronomer John Bevis recorded an observation of a faint nebulosity. In 1758, French comet-hunter Charles Messier spotted the hazy patch. It became the first entry in his catalog of objects that were fuzzy but not comets, now known as the Messier Catalog. Thus, the Crab nebula has the name M1.

In 1844, astronomer William Parsons – the 3rd Earl of Rosse – observed M1 through his large telescope in Ireland. Because he described it as having a shape resembling a crab, that became its familiar nickname.

Yet it wasn’t until 1921 that people made the association between the Crab nebula and Chinese records of the 1054 guest star.

How to see the Crab nebula

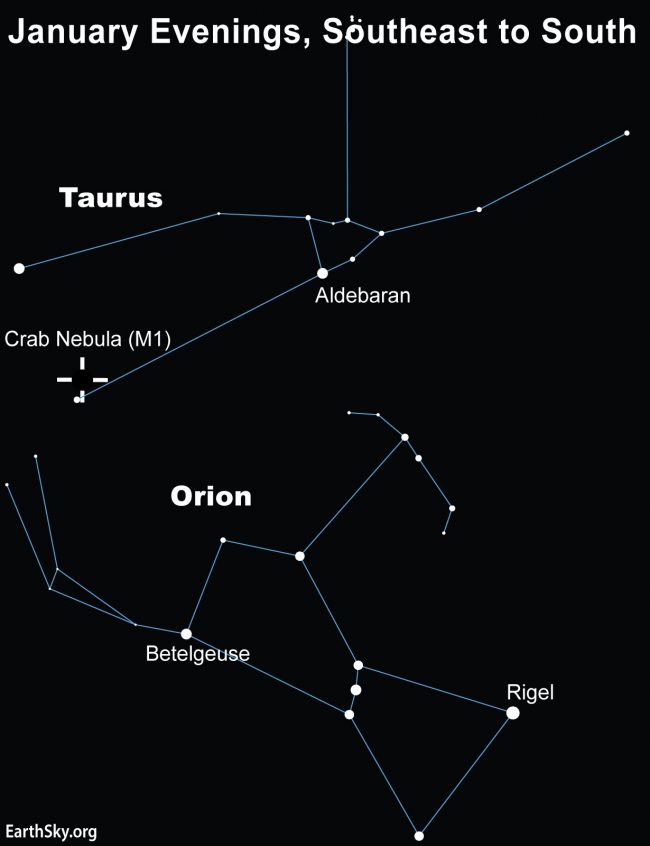

Since this beautiful nebula shines at magnitude 8.4, it requires magnification to see. Fortunately, it’s relatively easy to find with binoculars or a telescope due to its location near several bright stars. Plus, it’s near several recognizable constellations. Although you can see it at some time of night all year except – from roughly May through July when it’s too close to the sun – the best observing is late in the Northern Hemisphere fall through early spring. And from the late spring to early fall in the Southern Hemisphere. Most Southern Hemisphere viewers can see it except for the extreme southern portions of the globe.

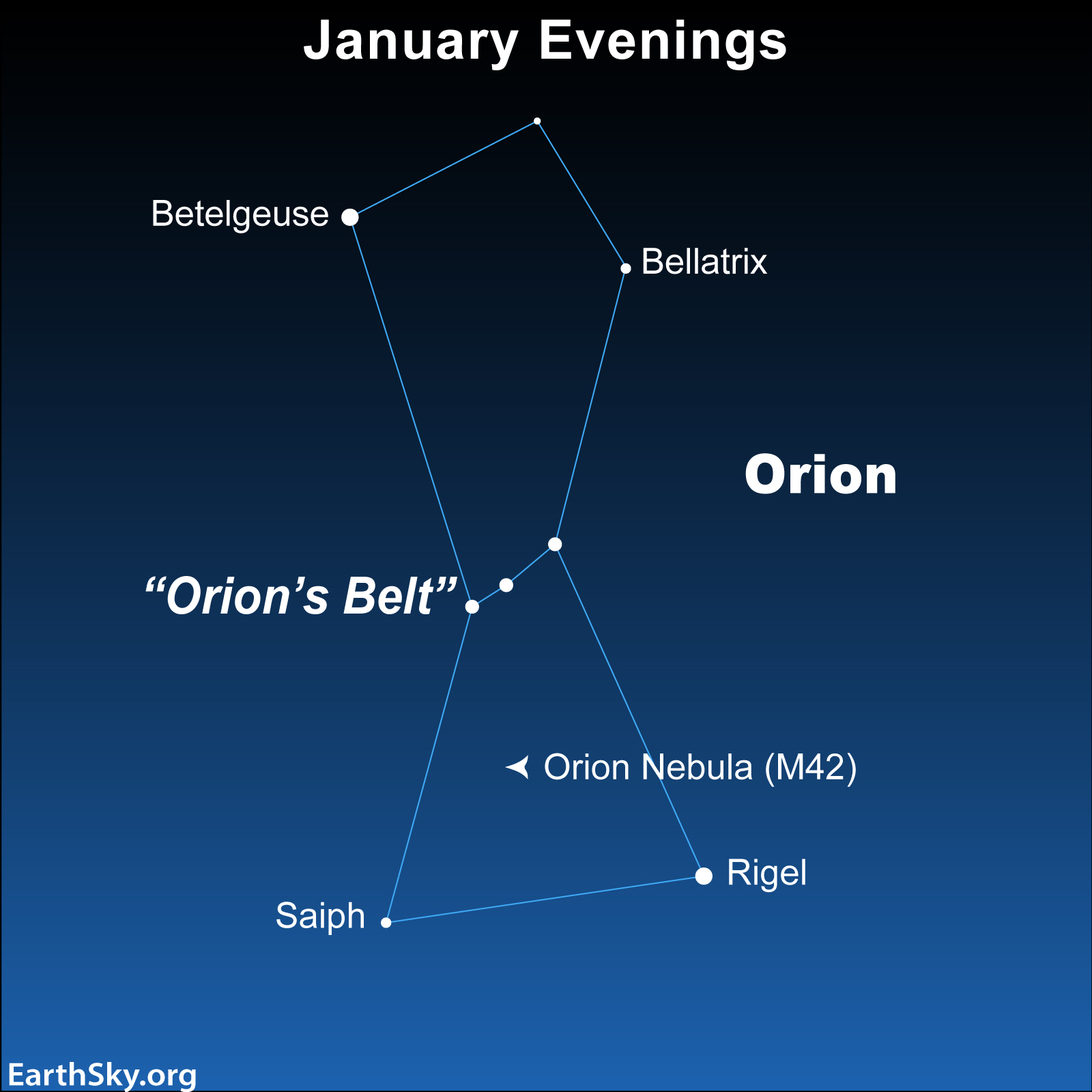

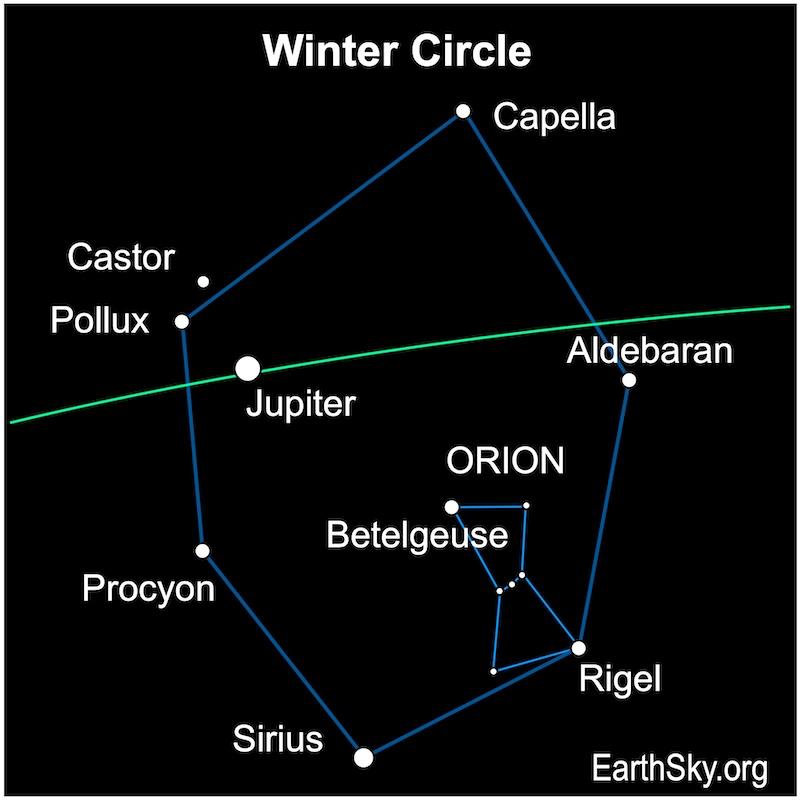

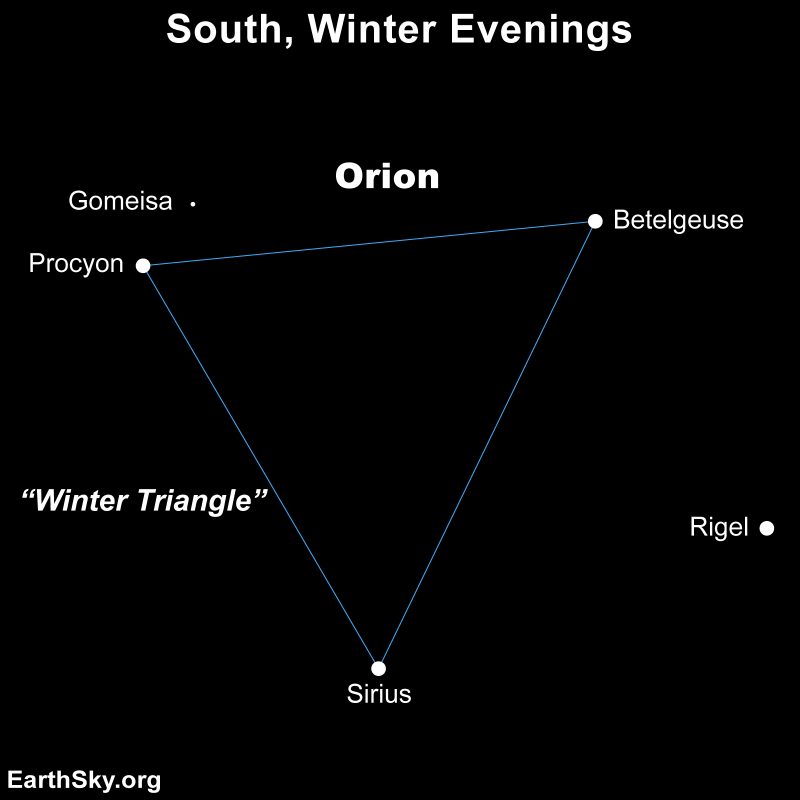

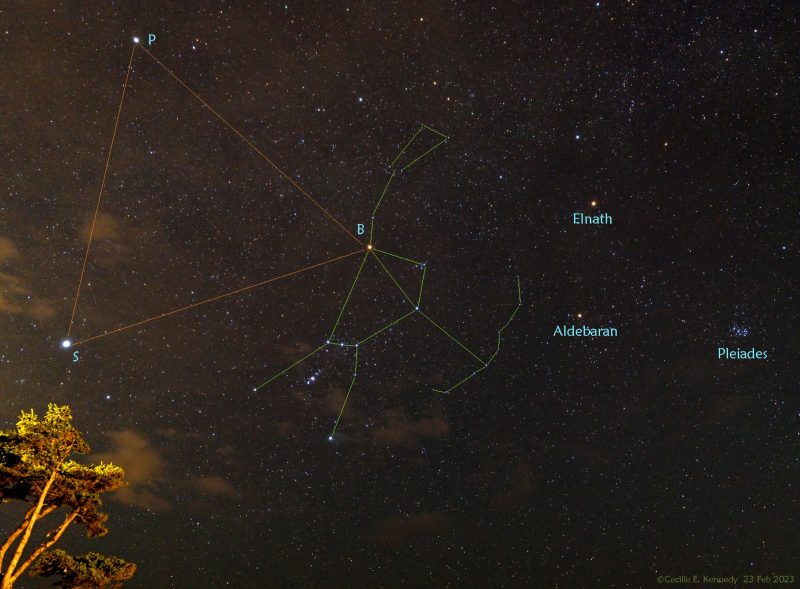

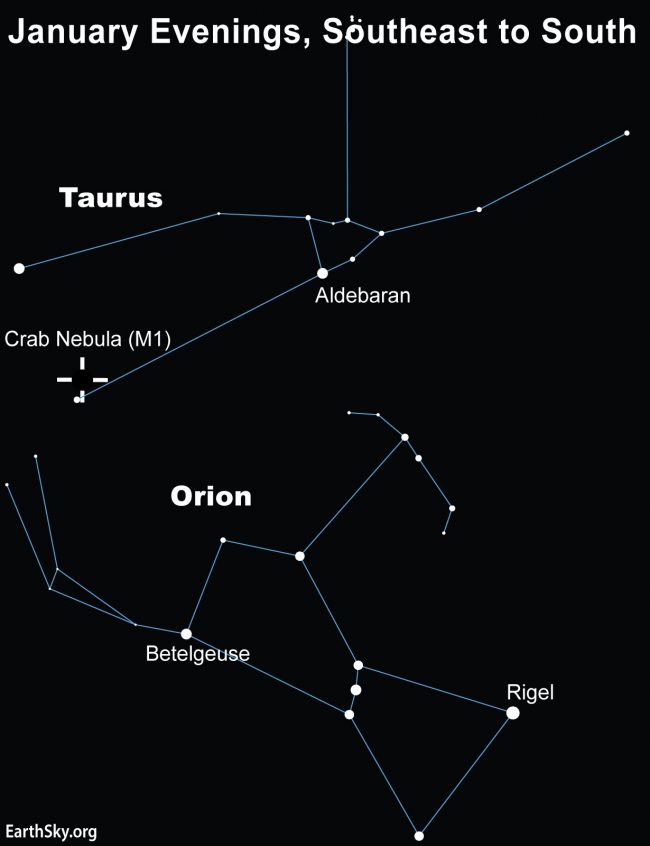

To find the Crab nebula, first draw an imaginary line from bright Betelgeuse in Orion to Capella in Auriga. About halfway along that line is the star Beta Tauri (or Elnath) on the Taurus-Auriga border.

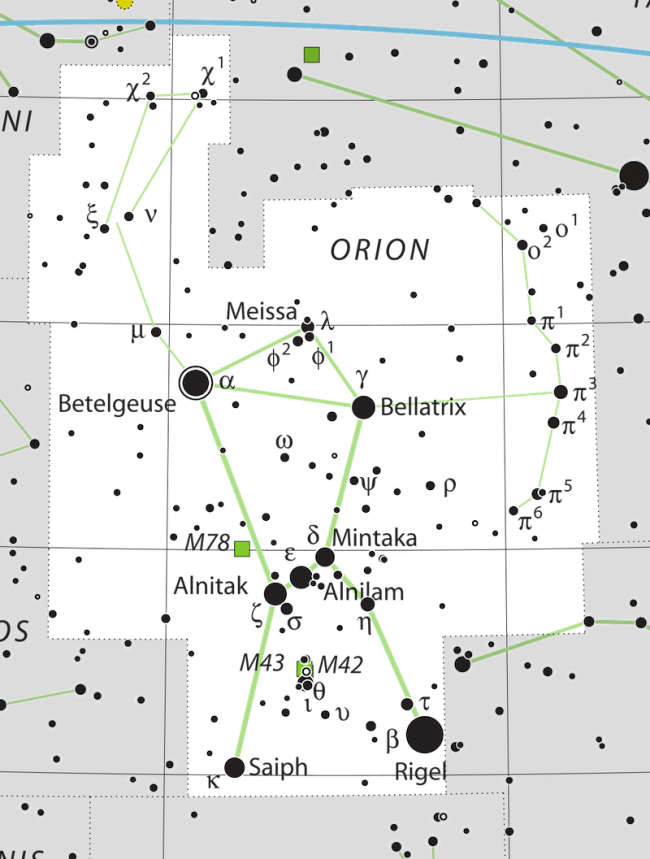

Having identified Beta Tauri, backtrack a little more than a 3rd of the way back to Betelgeuse to find the fainter star Zeta Tauri. Scanning the area around Zeta Tauri should reveal a tiny, faint smudge. It’s about a degree (twice the width of the full moon) from Zeta Tauri and more or less in the direction of Beta Tauri.

Views through binoculars or a telescope

Binoculars and small telescopes are useful for finding the object and showing its roughly oblong shape. However, they won’t show the filamentary structure or any of its internal detail. Here are two examples showing what to expect in binoculars or through a telescope.

First, the eyepiece view, above, simulates a 7-degree field of view centered around Zeta Tauri. This is what you might expect from a 7 X 50 pair of binoculars. Of course, the exact orientation and visibility will range widely depending on time of observation, sky conditions and so on. Scan around Zeta Tauri for the faint nebulosity.

Then the second image, above, simulates an approximately 3.5-degree view that you might see through a small telescope or finder scope. To give you a clear idea of scale, two full moons would fit with room to spare in the space between Zeta Tauri and the Crab nebula in this chart.

Keep in mind that exact conditions will vary.

Science of the Crab nebula

The Crab nebula is an oval gaseous nebula with fine filamentary (thread-like) structures, expanding at around 930 miles (1,500 km) per second. In its heart is a neutron star about the mass of the sun but only about 12-19 miles (20-30 km) in diameter. This neutron star is also a pulsar that spins about 30 times per second. The neutron star’s powerful magnetic field concentrates radiation emitted by the star as two beams that appear to flash periodically as the beams sweep into view. It lies about 6,500 light-years from Earth.

The Crab nebula may be from a new type of supernova

For a long time scientists thought the Crab nebula was the remnant of a type II supernova. But in June 2021, scientists announced they’d finally found evidence for a new type of supernova, an electron-capture supernova. Consequently, they now believe the Crab nebula may be this type of supernova. Read more about this exciting discovery.

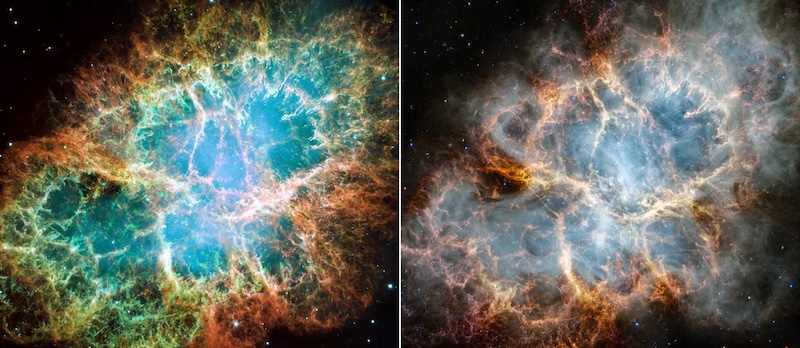

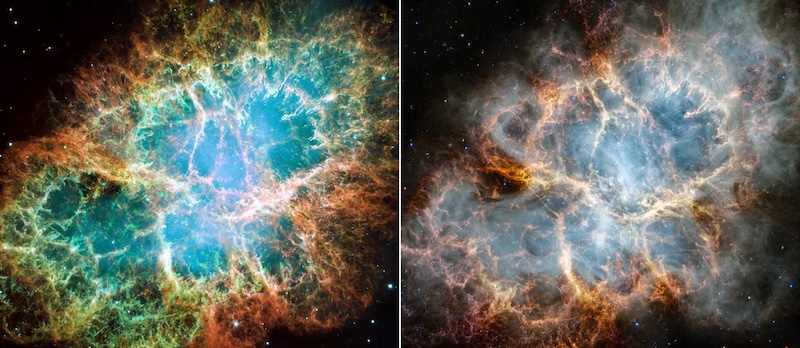

Views from the Hubble and Webb space telescopes

Views for our Community Photos

The center of the Crab nebula is approximately at RA: 5h 34m 32s; Dec: +22° 0′ 52″

Bottom line: The Crab nebula is visible with binoculars and small telescopes, and relatively easy to find since it’s near bright stars in prominent constellations. Although astronomers long thought that it was the remnant of a type II supernova, there’s increasing evidence that it may have been a new type of supernova called an electron capture supernova.

The post Meet the Crab nebula, remnant of an exploding star first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/rakH7Qs

A supernova explodes

The Crab nebula is a supernova remnant. It’s what’s left of an exploded star. A vast expanding cloud of gas and dust surrounding one of the densest objects in the universe, a neutron star.

Chinese astronomers noticed the sudden appearance of a star blazing in the daytime sky on July 4, 1054 CE. It likely outshone the brightest planet, Venus, and was temporarily the 3rd-brightest object in the sky, after the sun and moon. This “guest star” – the exploding supernova – remained visible in daylight for some 23 days. At night it shone near Tianguan – a star we now call Zeta Tauri, in the constellation Taurus the Bull – for nearly two years. Then it faded from view.

The supernova erupted – and the Crab nebula formed – about 6,500 light-years away.

The Crab nebula and supernova in history

The ancestral Puebloan people in the American Southwest may have viewed the bright new star in 1054. A crescent moon was in the sky near the new star on the morning of July 5, the day following the observations by the Chinese. So the pictograph below, from Chaco Canyon in New Mexico, might depict the event. The multi-spiked star to the left represents the supernova near the crescent moon. Furthermore, the handprint above may signify the importance of the event or may be the artist’s signature.

After exploding onto the scene in 1054 and shining brightly for two years, there are no reports of anything unusual in this spot in the sky until 1731. Then in that year, English amateur astronomer John Bevis recorded an observation of a faint nebulosity. In 1758, French comet-hunter Charles Messier spotted the hazy patch. It became the first entry in his catalog of objects that were fuzzy but not comets, now known as the Messier Catalog. Thus, the Crab nebula has the name M1.

In 1844, astronomer William Parsons – the 3rd Earl of Rosse – observed M1 through his large telescope in Ireland. Because he described it as having a shape resembling a crab, that became its familiar nickname.

Yet it wasn’t until 1921 that people made the association between the Crab nebula and Chinese records of the 1054 guest star.

How to see the Crab nebula

Since this beautiful nebula shines at magnitude 8.4, it requires magnification to see. Fortunately, it’s relatively easy to find with binoculars or a telescope due to its location near several bright stars. Plus, it’s near several recognizable constellations. Although you can see it at some time of night all year except – from roughly May through July when it’s too close to the sun – the best observing is late in the Northern Hemisphere fall through early spring. And from the late spring to early fall in the Southern Hemisphere. Most Southern Hemisphere viewers can see it except for the extreme southern portions of the globe.

To find the Crab nebula, first draw an imaginary line from bright Betelgeuse in Orion to Capella in Auriga. About halfway along that line is the star Beta Tauri (or Elnath) on the Taurus-Auriga border.

Having identified Beta Tauri, backtrack a little more than a 3rd of the way back to Betelgeuse to find the fainter star Zeta Tauri. Scanning the area around Zeta Tauri should reveal a tiny, faint smudge. It’s about a degree (twice the width of the full moon) from Zeta Tauri and more or less in the direction of Beta Tauri.

Views through binoculars or a telescope

Binoculars and small telescopes are useful for finding the object and showing its roughly oblong shape. However, they won’t show the filamentary structure or any of its internal detail. Here are two examples showing what to expect in binoculars or through a telescope.

First, the eyepiece view, above, simulates a 7-degree field of view centered around Zeta Tauri. This is what you might expect from a 7 X 50 pair of binoculars. Of course, the exact orientation and visibility will range widely depending on time of observation, sky conditions and so on. Scan around Zeta Tauri for the faint nebulosity.

Then the second image, above, simulates an approximately 3.5-degree view that you might see through a small telescope or finder scope. To give you a clear idea of scale, two full moons would fit with room to spare in the space between Zeta Tauri and the Crab nebula in this chart.

Keep in mind that exact conditions will vary.

Science of the Crab nebula

The Crab nebula is an oval gaseous nebula with fine filamentary (thread-like) structures, expanding at around 930 miles (1,500 km) per second. In its heart is a neutron star about the mass of the sun but only about 12-19 miles (20-30 km) in diameter. This neutron star is also a pulsar that spins about 30 times per second. The neutron star’s powerful magnetic field concentrates radiation emitted by the star as two beams that appear to flash periodically as the beams sweep into view. It lies about 6,500 light-years from Earth.

The Crab nebula may be from a new type of supernova

For a long time scientists thought the Crab nebula was the remnant of a type II supernova. But in June 2021, scientists announced they’d finally found evidence for a new type of supernova, an electron-capture supernova. Consequently, they now believe the Crab nebula may be this type of supernova. Read more about this exciting discovery.

Views from the Hubble and Webb space telescopes

Views for our Community Photos

The center of the Crab nebula is approximately at RA: 5h 34m 32s; Dec: +22° 0′ 52″

Bottom line: The Crab nebula is visible with binoculars and small telescopes, and relatively easy to find since it’s near bright stars in prominent constellations. Although astronomers long thought that it was the remnant of a type II supernova, there’s increasing evidence that it may have been a new type of supernova called an electron capture supernova.

The post Meet the Crab nebula, remnant of an exploding star first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/rakH7Qs

This star chart shows the location of Comet 2025 R3 (PanSTARRS) at 5:30 a.m. CDT on April 15, 2026. It will be near the variable star 75 Pegasus, within the

This star chart shows the location of Comet 2025 R3 (PanSTARRS) at 5:30 a.m. CDT on April 15, 2026. It will be near the variable star 75 Pegasus, within the