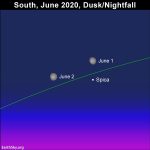

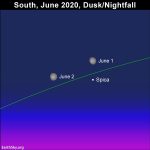

On June 1 and 2, 2020, use the waxing gibbous moon to find Spica, the brightest star in the constellation Virgo the Maiden. In fact, Spica is Virgo’s one and only 1st-magnitude star. Although the bright moon will wipe out a number of fainter stars from the canopy of night tonight, bright Spica should withstand the moonlit glare. If you have trouble seeing Spica, place your finger over the moon and look for a bright star nearby.

We in the Northern Hemisphere associate the star Spica with the spring and summer seasons. That’s because Spica first lights up the early evening sky in late March or early April, and then disappears from the evening sky around the September equinox.

The constellation Virgo stands as a memorial to that old legend of Hades, god of the underworld, who was said to have abducted Persephone, daughter of Demeter, goddess of the harvest. According to the legend, Hades took Persephone to his underground hideaway. Demeter’s grief was so great that she abandoned her role in insuring fruitfulness and fertility. In some parts of the globe, it’s said, winter cold came out of season and turned the once-verdant Earth in to a frigid wasteland. Elsewhere, summer heat was said to scorch the Earth and give rise to pestilence and disease. According to the myth, Earth would not bear fruit again until Demeter was reunited with her daughter.

Zeus, the king of the gods, intervened, insisting that Persephone be returned to her mother. However, Persephone was instructed to abstain from food until the reunion with her mother was a done deal. Alas, Hades purposely gave Persephone a pomegranate to take along, knowing she would eat a few seeds on her way home. Because of Persephone’s slip-up, Persephone has to return to the underworld for a number of months each year. When she does so, Demeter grieves, and winter reigns.

The constellation Virgo is linked to Demeter (and also Ishtar of Babylonian mythology, Isis of Egyptian mythology and Ceres of Roman mythology). Virgo is seen as a Maiden, associated with the harvest and fertility. The Latin word spicum refers to the ear of wheat Virgo holds in her left hand. The star Spica takes its name from this ear of wheat. Each evening, if you watch at the same time, you’ll see Spica slowly shift westward, toward the sunset direction. Eventually, Spica will get so close to the sunset that it’ll fade into the glare of evening twilight. Once Spica disappears from the evening sky, we at northerly latitudes must harvest our crops and put away firewood, because the cold winter season is on its way.

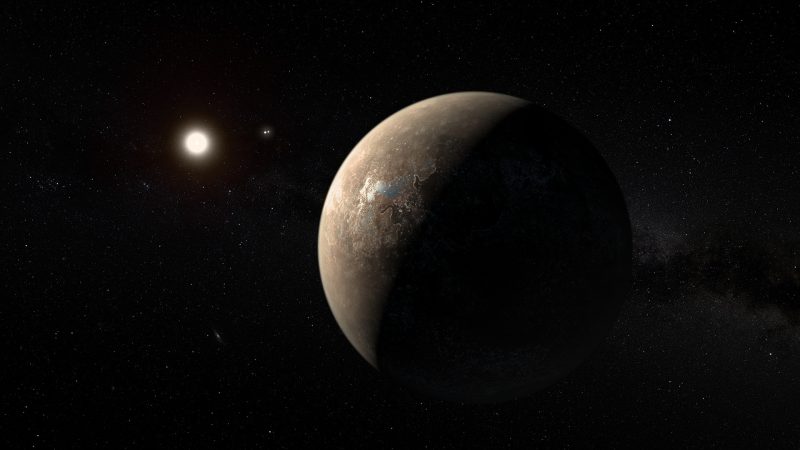

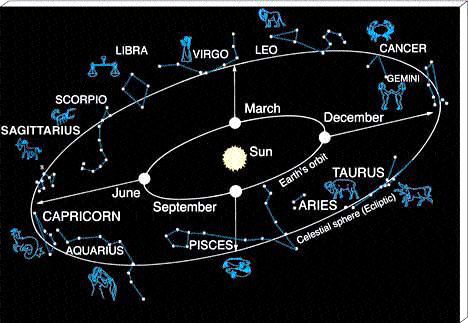

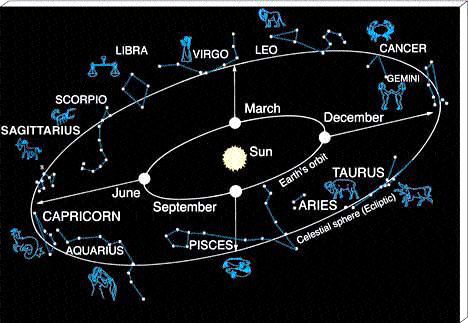

We are surrounded by stars. Because Earth orbits in a flat plane around the sun, we see the sun against the same stars again and again throughout the year. Those constellations, which have been special to people throughout the ages, are the constellations of the zodiac. Image via Professor Marcia Rieke.

The constellations of the zodiac – like Virgo – define the sun’s path across our sky. Putting it another way, each year, the sun passes in front of all the constellations of the zodiac. This year, 2020, the sun leaves the constellation Leo to enter the constellation Virgo on September 16, 2020. Then the sun leaves the constellation Virgo to enter the constellation Libra on October 30, 2020 (one day before Halloween).

Three other 1st-magnitude zodiacal stars join up with Spica to help sky gazers to envision the ecliptic – the sun’s annual path in front of the backdrop stars: Aldebaran, Regulus and Antares. Every year, the sun has its annual conjunction with Aldebaran on or near June 1, Regulus on or near August 23, Spica around mid-October, and Antares on or near December 1.

Of course, all these stars are invisible on their conjunction dates with the sun because they are totally lost in the sun’s glare at that time. However, six months before or after these stars’ conjunction dates, these stars are out all night long. Six months one way or the other of their conjunction, these stars reside opposite the sun in the sky and therefore stay out all night (Regulus around February 23, Spica around mid-April, Antares around June 1 and Aldebaran around December 1).

The ecliptic – Earth’s orbital plane projected onto the constellations of the zodiac – crosses the celestial equator (declination of O degrees) in the constellation Virgo. Because Spica resides so close to the ecliptic, it is considered a major star of the zodiac. Virgo constellation chart via the International Astronomical Union (IAU).

Bottom line: Use the moon to see the star Spica at nightfall on June 1 and 2, 2020, and celebrate this star’s presence in the evening sky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2XJrJcc

On June 1 and 2, 2020, use the waxing gibbous moon to find Spica, the brightest star in the constellation Virgo the Maiden. In fact, Spica is Virgo’s one and only 1st-magnitude star. Although the bright moon will wipe out a number of fainter stars from the canopy of night tonight, bright Spica should withstand the moonlit glare. If you have trouble seeing Spica, place your finger over the moon and look for a bright star nearby.

We in the Northern Hemisphere associate the star Spica with the spring and summer seasons. That’s because Spica first lights up the early evening sky in late March or early April, and then disappears from the evening sky around the September equinox.

The constellation Virgo stands as a memorial to that old legend of Hades, god of the underworld, who was said to have abducted Persephone, daughter of Demeter, goddess of the harvest. According to the legend, Hades took Persephone to his underground hideaway. Demeter’s grief was so great that she abandoned her role in insuring fruitfulness and fertility. In some parts of the globe, it’s said, winter cold came out of season and turned the once-verdant Earth in to a frigid wasteland. Elsewhere, summer heat was said to scorch the Earth and give rise to pestilence and disease. According to the myth, Earth would not bear fruit again until Demeter was reunited with her daughter.

Zeus, the king of the gods, intervened, insisting that Persephone be returned to her mother. However, Persephone was instructed to abstain from food until the reunion with her mother was a done deal. Alas, Hades purposely gave Persephone a pomegranate to take along, knowing she would eat a few seeds on her way home. Because of Persephone’s slip-up, Persephone has to return to the underworld for a number of months each year. When she does so, Demeter grieves, and winter reigns.

The constellation Virgo is linked to Demeter (and also Ishtar of Babylonian mythology, Isis of Egyptian mythology and Ceres of Roman mythology). Virgo is seen as a Maiden, associated with the harvest and fertility. The Latin word spicum refers to the ear of wheat Virgo holds in her left hand. The star Spica takes its name from this ear of wheat. Each evening, if you watch at the same time, you’ll see Spica slowly shift westward, toward the sunset direction. Eventually, Spica will get so close to the sunset that it’ll fade into the glare of evening twilight. Once Spica disappears from the evening sky, we at northerly latitudes must harvest our crops and put away firewood, because the cold winter season is on its way.

We are surrounded by stars. Because Earth orbits in a flat plane around the sun, we see the sun against the same stars again and again throughout the year. Those constellations, which have been special to people throughout the ages, are the constellations of the zodiac. Image via Professor Marcia Rieke.

The constellations of the zodiac – like Virgo – define the sun’s path across our sky. Putting it another way, each year, the sun passes in front of all the constellations of the zodiac. This year, 2020, the sun leaves the constellation Leo to enter the constellation Virgo on September 16, 2020. Then the sun leaves the constellation Virgo to enter the constellation Libra on October 30, 2020 (one day before Halloween).

Three other 1st-magnitude zodiacal stars join up with Spica to help sky gazers to envision the ecliptic – the sun’s annual path in front of the backdrop stars: Aldebaran, Regulus and Antares. Every year, the sun has its annual conjunction with Aldebaran on or near June 1, Regulus on or near August 23, Spica around mid-October, and Antares on or near December 1.

Of course, all these stars are invisible on their conjunction dates with the sun because they are totally lost in the sun’s glare at that time. However, six months before or after these stars’ conjunction dates, these stars are out all night long. Six months one way or the other of their conjunction, these stars reside opposite the sun in the sky and therefore stay out all night (Regulus around February 23, Spica around mid-April, Antares around June 1 and Aldebaran around December 1).

The ecliptic – Earth’s orbital plane projected onto the constellations of the zodiac – crosses the celestial equator (declination of O degrees) in the constellation Virgo. Because Spica resides so close to the ecliptic, it is considered a major star of the zodiac. Virgo constellation chart via the International Astronomical Union (IAU).

Bottom line: Use the moon to see the star Spica at nightfall on June 1 and 2, 2020, and celebrate this star’s presence in the evening sky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2XJrJcc