Tonight, assuming you’re in the Northern Hemisphere, you can easily find the legendary Big Dipper, called The Plough by our friends in the U.K. or The Wagon throughout much of Europe. This familiar star pattern is high in the north at nightfall in June. Find it, and let it be your guide to the Little Dipper, too.

You can find the Big Dipper easily because its shape really resembles a dipper. Meanwhile, the Little Dipper isn’t as easy to find. You need a dark sky to see the Little Dipper, so be sure to avoid city lights.

How do you find the Dippers? Assuming you’re in the Northern Hemisphere, simply face northward on a June evening, and watch for a large dipper-like pattern. That easy-to-see pattern will be the Big Dipper. Notice that the Big Dipper has two parts: a bowl and a handle. See the two outer stars in the bowl? They’re known as The Pointers because they point to the North Star, which is also known as Polaris.

Once you’ve found Polaris, you can find the Little Dipper. Polaris marks the end of the handle of the Little Dipper. You need a dark night to see the Little Dipper in full, because it’s so much fainter than its larger and brighter counterpart.

By the way, can you see the Big Dipper from Earth’s Southern Hemisphere? Yes, if you’re in the southern tropics. Much farther south, and it gets harder because as you go southward on Earth’s globe, the Dipper sinks closer and closer to the northern horizon.

Meanwhile, Polaris, the North Star, disappears beneath the horizon once you get south of the Earth’s equator.

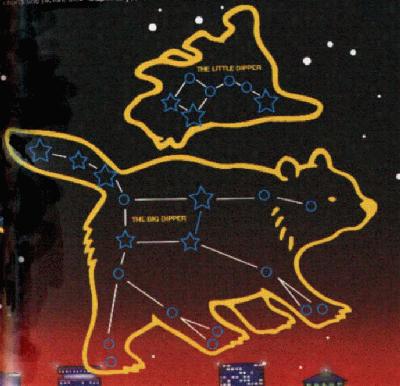

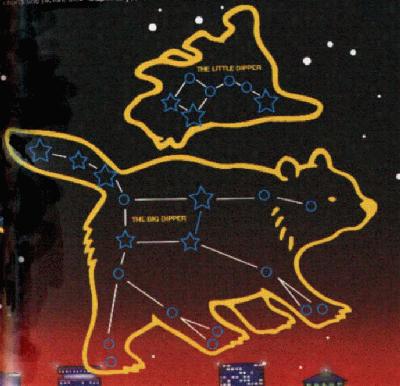

The Big and Little Dippers aren’t constellations. They’re asterisms, or noticeable star patterns. The Big Dipper is part of Ursa Major the Greater Bear. The Little Dipper belongs to Ursa Minor the Lesser Bear.

In his classic book “Star Names: Their Lore and Meaning,” Richard Hinckley Allen claims the Greek constellation Ursa Minor was never mentioned in the literary works of Homer (9th century B.C.) or Hesiod (8th century B.C.). That’s probably because this constellation hadn’t been invented yet, that long ago.

According to the Greek geographer and historian Strabo (63 B.C. to A.D. 21?), the seven stars we see today as part of Ursa Minor (the Little Dipper) didn’t carry that name until 600 B.C. or so. Before that time, people saw this group of stars outlining the wings of the constellation Draco the Dragon.

When the seafaring Phoenicians visited the Greek philosopher Thales around 600 B.C., they showed him how to navigate by the stars. Purportedly, Thales clipped the Dragon’s wings to create a new constellation, possibly because this new way of looking at the stars enabled Greek sailors to more easily locate the north celestial pole.

But it’s not just our names for things in the sky that change. The sky itself changes, too. In our day, Polaris closely marks the north celestial pole in the sky. In 600 B.C. – thanks to the motion of precession – the stars Kochab and Pherkad more closely marked the position of the north celestial pole.

Kochab and Pherkad: Guardians of the Pole

No matter what time of night it is – or what time of year it is – in other words, no matter how the Big Dipper is oriented in the sky, the 2 outer stars in its bowl always point to Polaris, the North Star. Image by EarthSky Facebook friend Abhijit Juvekar.

Bottom line: Look for the Big and Little Dippers in the north at nightfall!

Help EarthSky keep going! Please donate.

EarthSky astronomy kits are perfect for beginners. Order today from the EarthSky store

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/3dMXzeX

Tonight, assuming you’re in the Northern Hemisphere, you can easily find the legendary Big Dipper, called The Plough by our friends in the U.K. or The Wagon throughout much of Europe. This familiar star pattern is high in the north at nightfall in June. Find it, and let it be your guide to the Little Dipper, too.

You can find the Big Dipper easily because its shape really resembles a dipper. Meanwhile, the Little Dipper isn’t as easy to find. You need a dark sky to see the Little Dipper, so be sure to avoid city lights.

How do you find the Dippers? Assuming you’re in the Northern Hemisphere, simply face northward on a June evening, and watch for a large dipper-like pattern. That easy-to-see pattern will be the Big Dipper. Notice that the Big Dipper has two parts: a bowl and a handle. See the two outer stars in the bowl? They’re known as The Pointers because they point to the North Star, which is also known as Polaris.

Once you’ve found Polaris, you can find the Little Dipper. Polaris marks the end of the handle of the Little Dipper. You need a dark night to see the Little Dipper in full, because it’s so much fainter than its larger and brighter counterpart.

By the way, can you see the Big Dipper from Earth’s Southern Hemisphere? Yes, if you’re in the southern tropics. Much farther south, and it gets harder because as you go southward on Earth’s globe, the Dipper sinks closer and closer to the northern horizon.

Meanwhile, Polaris, the North Star, disappears beneath the horizon once you get south of the Earth’s equator.

The Big and Little Dippers aren’t constellations. They’re asterisms, or noticeable star patterns. The Big Dipper is part of Ursa Major the Greater Bear. The Little Dipper belongs to Ursa Minor the Lesser Bear.

In his classic book “Star Names: Their Lore and Meaning,” Richard Hinckley Allen claims the Greek constellation Ursa Minor was never mentioned in the literary works of Homer (9th century B.C.) or Hesiod (8th century B.C.). That’s probably because this constellation hadn’t been invented yet, that long ago.

According to the Greek geographer and historian Strabo (63 B.C. to A.D. 21?), the seven stars we see today as part of Ursa Minor (the Little Dipper) didn’t carry that name until 600 B.C. or so. Before that time, people saw this group of stars outlining the wings of the constellation Draco the Dragon.

When the seafaring Phoenicians visited the Greek philosopher Thales around 600 B.C., they showed him how to navigate by the stars. Purportedly, Thales clipped the Dragon’s wings to create a new constellation, possibly because this new way of looking at the stars enabled Greek sailors to more easily locate the north celestial pole.

But it’s not just our names for things in the sky that change. The sky itself changes, too. In our day, Polaris closely marks the north celestial pole in the sky. In 600 B.C. – thanks to the motion of precession – the stars Kochab and Pherkad more closely marked the position of the north celestial pole.

Kochab and Pherkad: Guardians of the Pole

No matter what time of night it is – or what time of year it is – in other words, no matter how the Big Dipper is oriented in the sky, the 2 outer stars in its bowl always point to Polaris, the North Star. Image by EarthSky Facebook friend Abhijit Juvekar.

Bottom line: Look for the Big and Little Dippers in the north at nightfall!

Help EarthSky keep going! Please donate.

EarthSky astronomy kits are perfect for beginners. Order today from the EarthSky store

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/3dMXzeX

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire