Artist’s concept of Proxima Centauri b and c – depicted here as 2 black dots, a larger one and a smaller one – orbiting their red dwarf star. Proxima Centauri c, the larger planet, might also have a ring system. Image via Michele Diodati/ Medium.

Just a few days ago, scientists announced that the closest known Earth-sized exoplanet, Proxima Centauri b, had been confirmed to orbit the nearest star to our solar system. That’s an exciting development, but now, as scientists announced on June 2, 2020, it seems that another possible planet around the same star also has been verified … Proxima Centauri c! Both planets are only 4.2 light-years away.

The peer-reviewed results were published in Research Notes of the AAS back in April. Astronomer Fritz Benedict of McDonald Observatory presented the findings at the virtual 236th meeting of the American Astronomical Society.

Evidence for Proxima Centauri c was first announced earlier this year by a research group led by Mario Damasso of Italy’s National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF). But the evidence wasn’t conclusive. This second planet for Proxima is apparently a lot larger than Earth and orbits its star every 1,907 days. It orbits at about 1.5 times the distance from its star that Earth orbits from the sun. Not an extreme difference, but Proxima Centauri is a red dwarf star, smaller and cooler than our sun, so at that distance, the planet can be expected to be significantly colder than Earth.

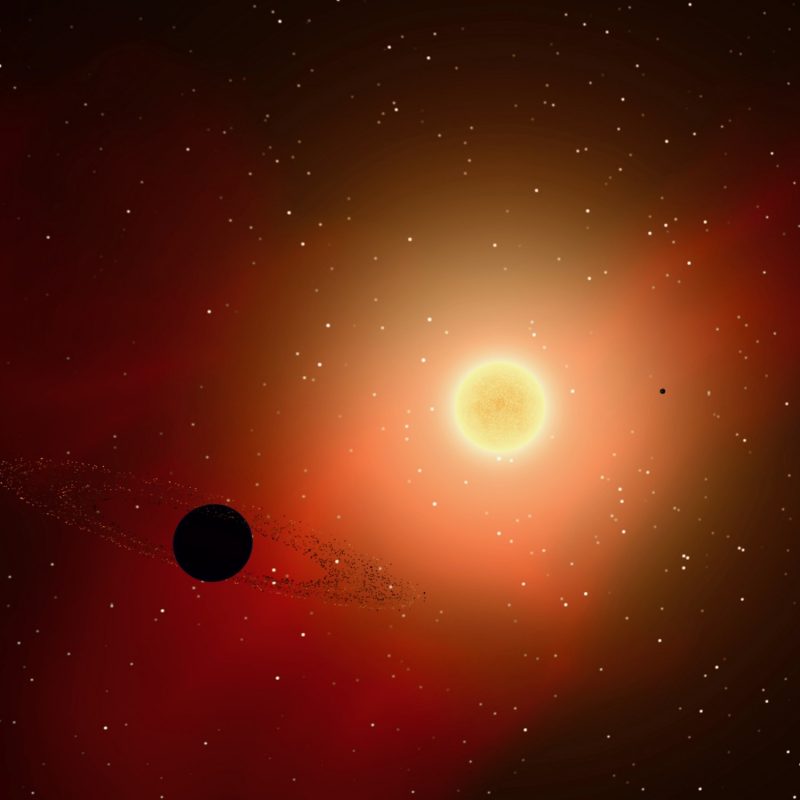

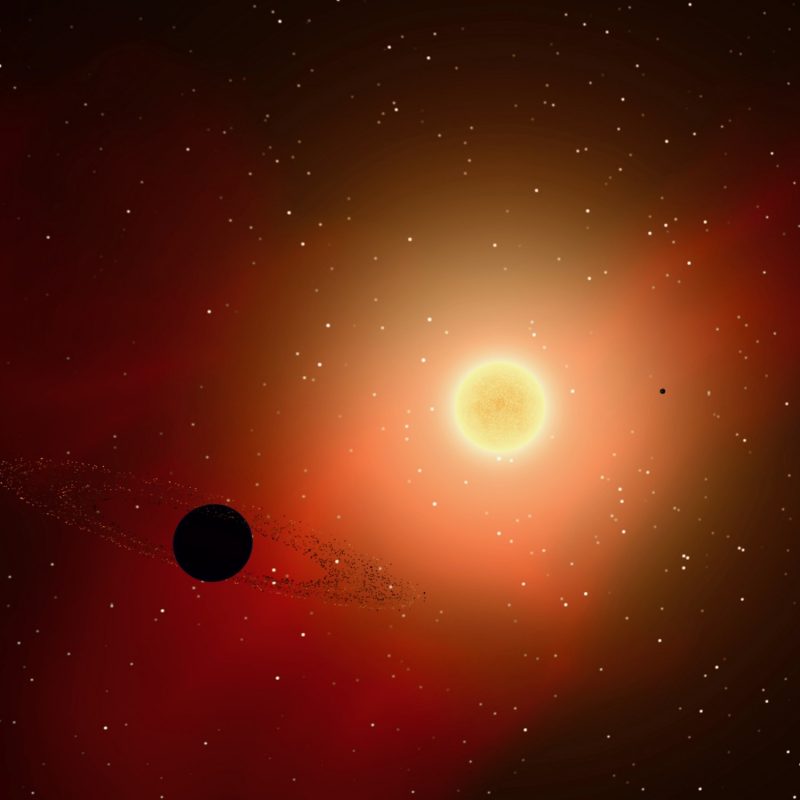

Combined images from the SPHERE instrument on the Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile, which appear to show Proxima Centauri c as a bright dot. The location is right where the planet was predicted to be in its orbit. The star is hidden behind the black circle in the center. Image via Gratton et al./ A&A/ Nature Astronomy.

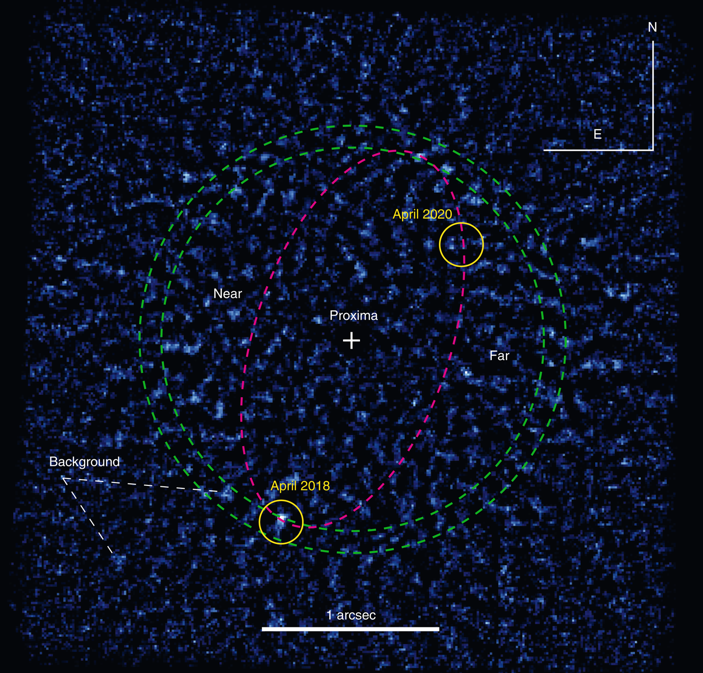

Even though Proxima Centauri is the closest star to the sun, it’s difficult to detect the planets orbiting it. Most exoplanets have been found via the transit method, and this system isn’t oriented with respect to Earth such that its planets transit in front of Proxima, from our perspective. So scientists have to use radial velocity observations, measurements of Proxima’s motion toward and away from Earth, to detect the tiny effects of the planets’ gravitational tuggings on the star.

Benedict’s idea was to look again at previous studies of the star from the 1990s from the Hubble Space Telescope (HST), which used the telescope’s Fine Guidance Sensors (FGS). The FGS can be used for astrometry, where scientists can take very accurate measurements of the positions and motions of objects in the sky. If Proxima Centauri c were really there, FGS should be able to detect it. Benedict said in a statement:

Basically, this is a story of how old data can be very useful when you get new information. It’s also a story of how hard it is to retire if you’re an astronomer, because this is fun stuff to do!

So what did Benedict and his team find?

When they looked at the old Hubble data, they found a planet with an orbital period of 1,907 days, which fit with what had been seen before, for the tentative Proxima Centauri c. The planet had been overlooked before because in the 1990s, researchers only checked the data for planets with orbital periods of less than 1,000 days.

Benedict combined the results of three studies: the Hubble/FGS astrometry, the radial velocity studies and images from the SPHERE instrument on the Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile, to better estimate the mass of Proxima Centauri c. He concluded that the planet is approximately seven times more massive than Earth.

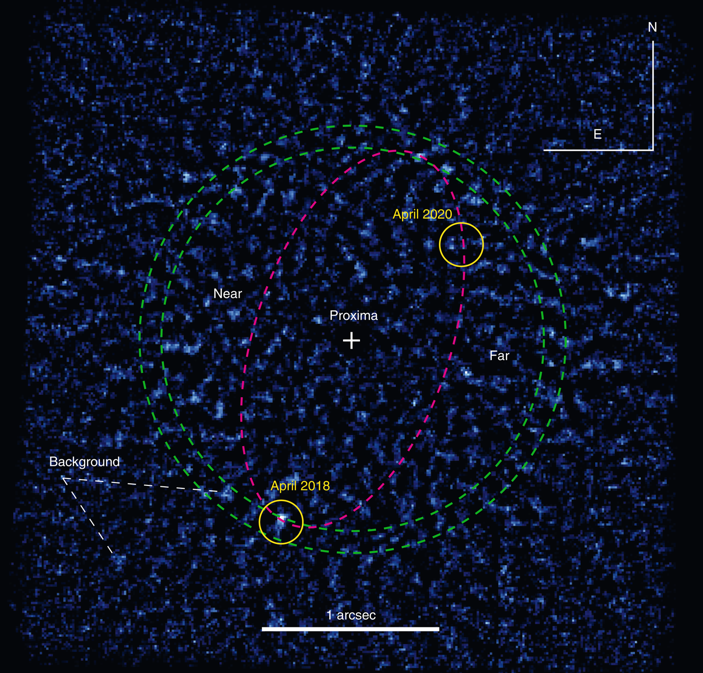

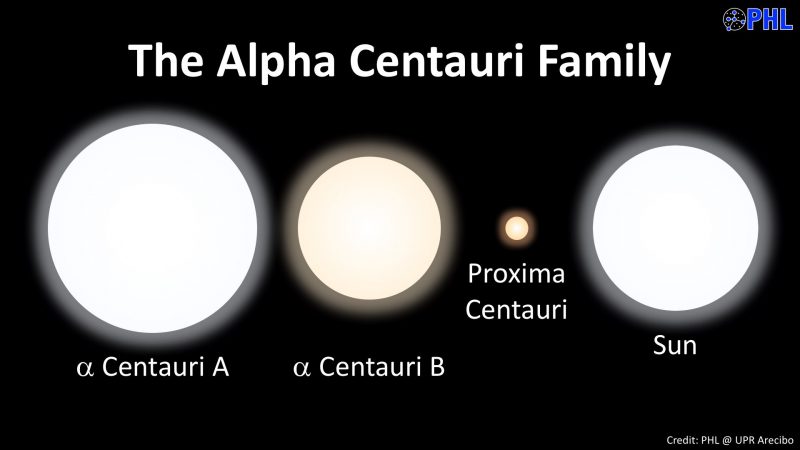

Size comparison of the three stars in the Alpha Centauri system, including Proxima Centauri, and the sun. Image via PHL @ UPR Arecibo.

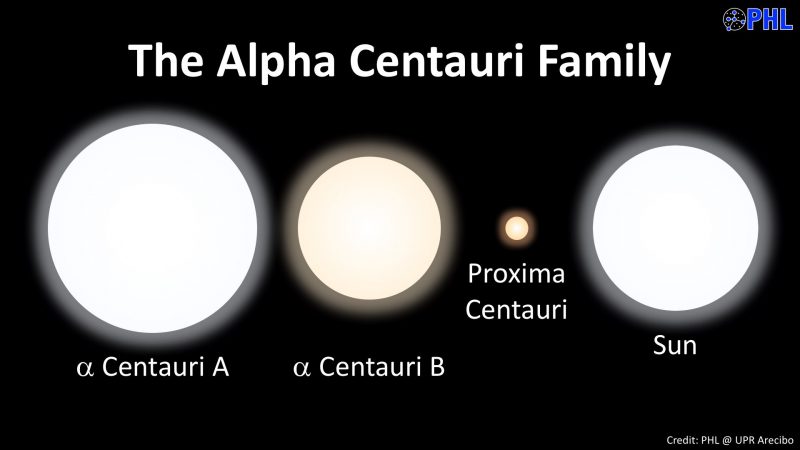

Proxima Centauri is the closest of the three stars in the Alpha Centauri system. Image via ESO/ BBC.

Earlier this year, scientists using the images from SPHERE found what appeared to be a large planet orbiting Proxima Centauri that coincided with the predicted position of Proxima Centauri c at the time.

But based on those images, it was found that Proxima Centauri c appeared to be brighter than expected. If the brightness was entirely from the light reflected off the planet itself, then the planet would be about five times larger than Jupiter. But since its estimated mass is more similar to Neptune’s, it may actually be smaller, but has dust clouds or a huge ring system around it. Determining whether it actually does or not will require more observations. It is bright enough that better images of it should be able to be taken by upcoming space telescopes. That’s not the case, unfortunately, with Proxima Centauri b, since it is smaller and much closer to the star. From another recent paper:

Proxima c could become a prime target for follow-up and characterization with next-generation direct imaging instrumentation due to the large maximum angular separation of ~1 arc second from the parent star. The candidate planet represents a challenge for the models of super-Earth formation and evolution.

As far as possible life is concerned, Proxima Centauri c may be too cold for life as we know it, but we just don’t know enough about it yet. Proxima Centauri b is a better candidate for being potentially habitable, since it is only slightly larger than Earth, orbits in the habitable zone of its star and is estimated to have similar temperatures to Earth. We don’t know enough about the actual conditions on this planet yet either, however.

Fritz Benedict at McDonald Observatory, lead author of the new study. Image via McDonald Observatory.

With at least two planets now confirmed orbiting the closest star to our solar system, combined with the over 4,000 other exoplanets discovered so far, we now know that such exoworlds are common in our galaxy. That is a big step that brings us even closer to answering the biggest question of all: are we alone?

Bottom line: Astronomers at McDonald Observatory have confirmed a second planet orbiting the closest star to our sun.

Source: A Preliminary Mass for Proxima Centauri C

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2zlUV0O

Artist’s concept of Proxima Centauri b and c – depicted here as 2 black dots, a larger one and a smaller one – orbiting their red dwarf star. Proxima Centauri c, the larger planet, might also have a ring system. Image via Michele Diodati/ Medium.

Just a few days ago, scientists announced that the closest known Earth-sized exoplanet, Proxima Centauri b, had been confirmed to orbit the nearest star to our solar system. That’s an exciting development, but now, as scientists announced on June 2, 2020, it seems that another possible planet around the same star also has been verified … Proxima Centauri c! Both planets are only 4.2 light-years away.

The peer-reviewed results were published in Research Notes of the AAS back in April. Astronomer Fritz Benedict of McDonald Observatory presented the findings at the virtual 236th meeting of the American Astronomical Society.

Evidence for Proxima Centauri c was first announced earlier this year by a research group led by Mario Damasso of Italy’s National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF). But the evidence wasn’t conclusive. This second planet for Proxima is apparently a lot larger than Earth and orbits its star every 1,907 days. It orbits at about 1.5 times the distance from its star that Earth orbits from the sun. Not an extreme difference, but Proxima Centauri is a red dwarf star, smaller and cooler than our sun, so at that distance, the planet can be expected to be significantly colder than Earth.

Combined images from the SPHERE instrument on the Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile, which appear to show Proxima Centauri c as a bright dot. The location is right where the planet was predicted to be in its orbit. The star is hidden behind the black circle in the center. Image via Gratton et al./ A&A/ Nature Astronomy.

Even though Proxima Centauri is the closest star to the sun, it’s difficult to detect the planets orbiting it. Most exoplanets have been found via the transit method, and this system isn’t oriented with respect to Earth such that its planets transit in front of Proxima, from our perspective. So scientists have to use radial velocity observations, measurements of Proxima’s motion toward and away from Earth, to detect the tiny effects of the planets’ gravitational tuggings on the star.

Benedict’s idea was to look again at previous studies of the star from the 1990s from the Hubble Space Telescope (HST), which used the telescope’s Fine Guidance Sensors (FGS). The FGS can be used for astrometry, where scientists can take very accurate measurements of the positions and motions of objects in the sky. If Proxima Centauri c were really there, FGS should be able to detect it. Benedict said in a statement:

Basically, this is a story of how old data can be very useful when you get new information. It’s also a story of how hard it is to retire if you’re an astronomer, because this is fun stuff to do!

So what did Benedict and his team find?

When they looked at the old Hubble data, they found a planet with an orbital period of 1,907 days, which fit with what had been seen before, for the tentative Proxima Centauri c. The planet had been overlooked before because in the 1990s, researchers only checked the data for planets with orbital periods of less than 1,000 days.

Benedict combined the results of three studies: the Hubble/FGS astrometry, the radial velocity studies and images from the SPHERE instrument on the Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile, to better estimate the mass of Proxima Centauri c. He concluded that the planet is approximately seven times more massive than Earth.

Size comparison of the three stars in the Alpha Centauri system, including Proxima Centauri, and the sun. Image via PHL @ UPR Arecibo.

Proxima Centauri is the closest of the three stars in the Alpha Centauri system. Image via ESO/ BBC.

Earlier this year, scientists using the images from SPHERE found what appeared to be a large planet orbiting Proxima Centauri that coincided with the predicted position of Proxima Centauri c at the time.

But based on those images, it was found that Proxima Centauri c appeared to be brighter than expected. If the brightness was entirely from the light reflected off the planet itself, then the planet would be about five times larger than Jupiter. But since its estimated mass is more similar to Neptune’s, it may actually be smaller, but has dust clouds or a huge ring system around it. Determining whether it actually does or not will require more observations. It is bright enough that better images of it should be able to be taken by upcoming space telescopes. That’s not the case, unfortunately, with Proxima Centauri b, since it is smaller and much closer to the star. From another recent paper:

Proxima c could become a prime target for follow-up and characterization with next-generation direct imaging instrumentation due to the large maximum angular separation of ~1 arc second from the parent star. The candidate planet represents a challenge for the models of super-Earth formation and evolution.

As far as possible life is concerned, Proxima Centauri c may be too cold for life as we know it, but we just don’t know enough about it yet. Proxima Centauri b is a better candidate for being potentially habitable, since it is only slightly larger than Earth, orbits in the habitable zone of its star and is estimated to have similar temperatures to Earth. We don’t know enough about the actual conditions on this planet yet either, however.

Fritz Benedict at McDonald Observatory, lead author of the new study. Image via McDonald Observatory.

With at least two planets now confirmed orbiting the closest star to our solar system, combined with the over 4,000 other exoplanets discovered so far, we now know that such exoworlds are common in our galaxy. That is a big step that brings us even closer to answering the biggest question of all: are we alone?

Bottom line: Astronomers at McDonald Observatory have confirmed a second planet orbiting the closest star to our sun.

Source: A Preliminary Mass for Proxima Centauri C

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2zlUV0O

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire