By Carol Clark

Just as the steam engine set the stage for the Industrial Revolution, and micro transistors sparked the digital age, nanoscale devices made from DNA are opening up a new era in bio-medical research and materials science.

The journal Science describes the emerging uses of DNA mechanical devices in a “Perspective” article by Khalid Salaita, a professor of chemistry at Emory University, and Aaron Blanchard, a graduate student in the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering, a joint program of Georgia Institute of Technology and Emory.

The article heralds a new field, which Blanchard dubbed “DNA mechanotechnology,” to engineer DNA machines that generate, transmit and sense mechanical forces at the nanoscale.

“For a long time,” Salaita says, “scientists have been good at making micro devices, hundreds of times smaller than the width of a human hair. It’s been more challenging to make functional nano devices, thousands of times smaller than that. But using DNA as the component parts is making it possible to build extremely elaborate nano devices because the DNA parts self-assemble.”

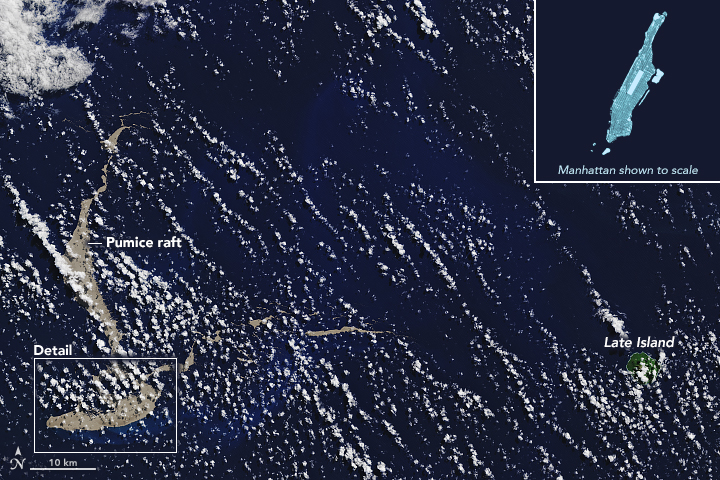

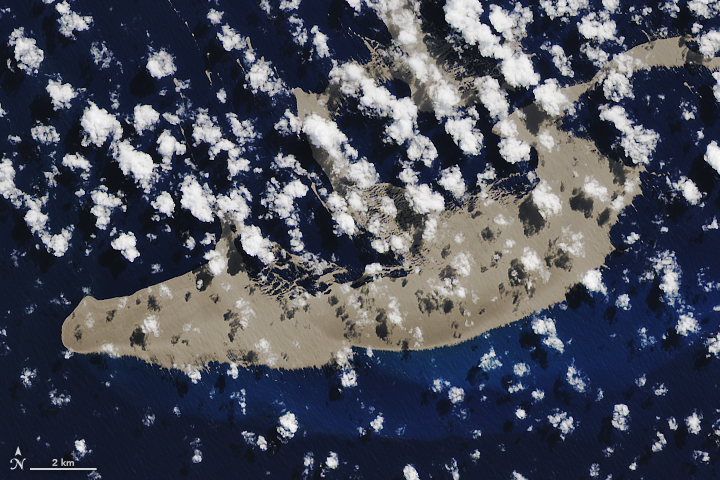

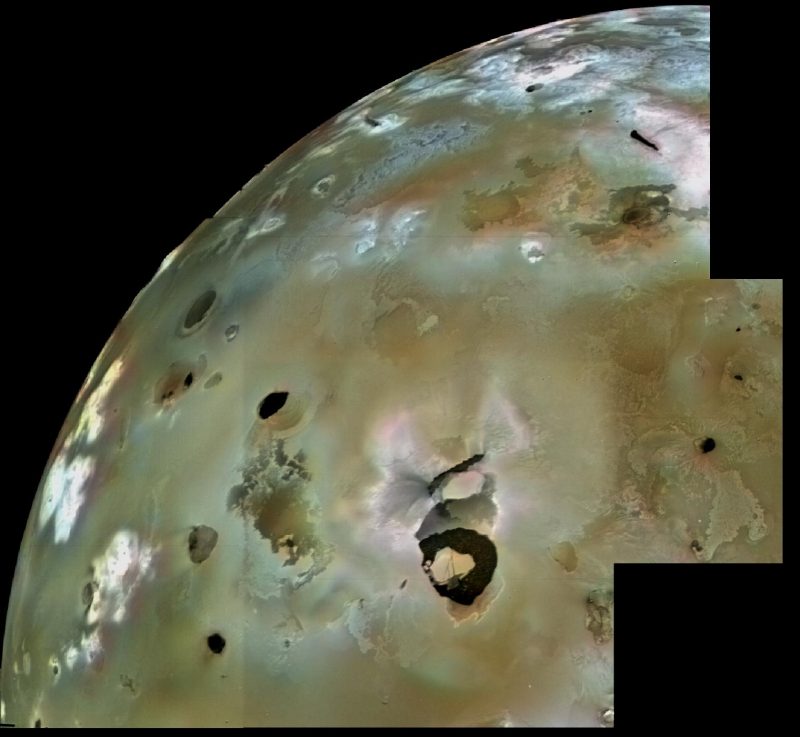

"DNA mechanotechnology expands the opportunities for research involving biomedicine and materials science," Salaita says. (Graphic by Salaita Lab)

DNA, or deoxyribonucleic acid, stores and transmits genetic information as a code made up of four chemical bases: adenine (A), guanine (G), cytosine (C) and thymine (T). The DNA bases have a natural affinity to pair up with each other — A with T and C with G. Synthetic strands of DNA can be combined with natural DNA strands from bacteriophages. By moving around the sequence of letters on the strands, researchers can get the DNA strands to bind together in ways that create different shapes. The stiffness of DNA strands can also easily be adjusted, so they remain straight as a piece of dry spaghetti or bend and coil like boiled spaghetti.

The idea of using DNA as a construction material goes back to the 1980s, when biochemist Nadrian Seeman pioneered DNA nanotechnology. This field uses strands DNA to make functional devices at the nanoscale. The ability to make these precise, three-dimensional structures began as a novelty, nicknamed DNA origami, resulting in objects such as a microscopic map of the world and, more recently, the tiniest-ever game of tic-tac-toe, played on a DNA board.

Work on novelty objects continues to provide new insights into the mechanical properties of DNA. These insights are driving the ability to make DNA machines that generate, transmit and sense mechanical forces.

“If you put together these three main components of mechanical devices, you begin to get hammers and cogs and wheels and you can start building nano machines,” Salaita says. “DNA mechanotechnology expands the opportunities for research involving biomedicine and materials science. It’s like discovering a new continent and opening up fresh territory to explore.”

Watch a video about how DNA machines work

Potential uses for such devices include drug delivery devices in the form of nano capsules that open up when they reach a target site, nano computers and nano robots working on nanoscale assembly lines.

The use of DNA self-assembly by the genomics industry, for biomedical research and diagnostics, is further propelling DNA mechanotechnology, making DNA synthesis inexpensive and readily available. “Potentially anyone can dream up a nano-machine design and make it a reality,” Salaita says.

He gives the example of creating a pair of nano scissors. “You know that you need two rigid rods and that they need to be linked by a pivot mechanism,” he says. “By tinkering with some open-source software, you can create this design and then go onto a computer and place an order to custom synthesize your design. You’ll receive your order in a tube. You simply put the tube contents into a solution, let your device self-assemble, and then use a microscope to see if it works the way you thought that it would.”

The Salaita Lab is one of only about 100 around the world working at the forefront of DNA mechanotechnology. He and Blanchard developed the world’s strongest synthetic DNA-based motor, which was recently reported in Nano Letters.

A key focus of Salaita’s research is mapping and measuring how cells push and pull to learn more about the mechanical forces involved in the human immune system. Salaita developed the first DNA force gauges for cells, providing the first detailed view of the mechanical forces that one molecule applies to another molecule across the entire surface of a living cell. Mapping such forces may help to diagnose and treat diseases related to cellular mechanics. Cancer cells, for instance, move differently from normal cells, and it is unclear whether that difference is a cause or an effect of the disease.

Watch a video about the Salaita Lab's work with T cells

In 2016, Salaita used these DNA force gauges to provide the first direct evidence for the mechanical forces of T cells, the security guards of the immune system. His lab showed how T cells use a kind of mechanical “handshake” or tug to test whether a cell they encounter is a friend or foe. These mechanical tugs are central to a T cell’s decision for whether to mount an immune response.

“Your blood contains millions of different types of T cells, and each T cell is evolved to detect a certain pathogen or foreign agent,” Salaita explains. “T cells are constantly sampling cells throughout your body using these mechanical tugs. They bind and pull on proteins on a cell’s surface and, if the bond is strong, that’s a signal that the T cell has found a foreign agent.”

Salaita’s lab built on this discovery in a paper recently published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). Work led by Emory chemistry graduate student Rong Ma refined the sensitivity of the DNA force gauges. Not only can they detect these mechanical tugs at a force so slight that it is nearly one-billionth the weight of a paperclip, they can also capture evidence of tugs as brief as the blink of an eye.

The research provides an unprecedented look at the mechanical forces involved in the immune system. “We showed that, in addition to being evolved to detect certain foreign agents, T cells will also apply very brief mechanical tugs to foreign agents that are a near match,” Salaita says. “The frequency and duration of the tug depends on how closely the foreign agent is matched to the T cell receptor.”

The result provides a tool to predict how strong of an immune response a T cell will mount. “We hope this tool may eventually be used to fine tune immunotherapies for individual cancer patients,” Salaita says. “It could potentially help engineer T cells to go after particular cancer cells.”

Related:

Nano-walkers take speedy leap forward with first rolling DNA-based motor

T cells use 'handshakes' to sort friends from foes

New methods reveal the mechanics of blood clotting

Chemists reveal the force within you

from eScienceCommons https://ift.tt/2O9bEcO

By Carol Clark

Just as the steam engine set the stage for the Industrial Revolution, and micro transistors sparked the digital age, nanoscale devices made from DNA are opening up a new era in bio-medical research and materials science.

The journal Science describes the emerging uses of DNA mechanical devices in a “Perspective” article by Khalid Salaita, a professor of chemistry at Emory University, and Aaron Blanchard, a graduate student in the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering, a joint program of Georgia Institute of Technology and Emory.

The article heralds a new field, which Blanchard dubbed “DNA mechanotechnology,” to engineer DNA machines that generate, transmit and sense mechanical forces at the nanoscale.

“For a long time,” Salaita says, “scientists have been good at making micro devices, hundreds of times smaller than the width of a human hair. It’s been more challenging to make functional nano devices, thousands of times smaller than that. But using DNA as the component parts is making it possible to build extremely elaborate nano devices because the DNA parts self-assemble.”

"DNA mechanotechnology expands the opportunities for research involving biomedicine and materials science," Salaita says. (Graphic by Salaita Lab)

DNA, or deoxyribonucleic acid, stores and transmits genetic information as a code made up of four chemical bases: adenine (A), guanine (G), cytosine (C) and thymine (T). The DNA bases have a natural affinity to pair up with each other — A with T and C with G. Synthetic strands of DNA can be combined with natural DNA strands from bacteriophages. By moving around the sequence of letters on the strands, researchers can get the DNA strands to bind together in ways that create different shapes. The stiffness of DNA strands can also easily be adjusted, so they remain straight as a piece of dry spaghetti or bend and coil like boiled spaghetti.

The idea of using DNA as a construction material goes back to the 1980s, when biochemist Nadrian Seeman pioneered DNA nanotechnology. This field uses strands DNA to make functional devices at the nanoscale. The ability to make these precise, three-dimensional structures began as a novelty, nicknamed DNA origami, resulting in objects such as a microscopic map of the world and, more recently, the tiniest-ever game of tic-tac-toe, played on a DNA board.

Work on novelty objects continues to provide new insights into the mechanical properties of DNA. These insights are driving the ability to make DNA machines that generate, transmit and sense mechanical forces.

“If you put together these three main components of mechanical devices, you begin to get hammers and cogs and wheels and you can start building nano machines,” Salaita says. “DNA mechanotechnology expands the opportunities for research involving biomedicine and materials science. It’s like discovering a new continent and opening up fresh territory to explore.”

Watch a video about how DNA machines work

Potential uses for such devices include drug delivery devices in the form of nano capsules that open up when they reach a target site, nano computers and nano robots working on nanoscale assembly lines.

The use of DNA self-assembly by the genomics industry, for biomedical research and diagnostics, is further propelling DNA mechanotechnology, making DNA synthesis inexpensive and readily available. “Potentially anyone can dream up a nano-machine design and make it a reality,” Salaita says.

He gives the example of creating a pair of nano scissors. “You know that you need two rigid rods and that they need to be linked by a pivot mechanism,” he says. “By tinkering with some open-source software, you can create this design and then go onto a computer and place an order to custom synthesize your design. You’ll receive your order in a tube. You simply put the tube contents into a solution, let your device self-assemble, and then use a microscope to see if it works the way you thought that it would.”

The Salaita Lab is one of only about 100 around the world working at the forefront of DNA mechanotechnology. He and Blanchard developed the world’s strongest synthetic DNA-based motor, which was recently reported in Nano Letters.

A key focus of Salaita’s research is mapping and measuring how cells push and pull to learn more about the mechanical forces involved in the human immune system. Salaita developed the first DNA force gauges for cells, providing the first detailed view of the mechanical forces that one molecule applies to another molecule across the entire surface of a living cell. Mapping such forces may help to diagnose and treat diseases related to cellular mechanics. Cancer cells, for instance, move differently from normal cells, and it is unclear whether that difference is a cause or an effect of the disease.

Watch a video about the Salaita Lab's work with T cells

In 2016, Salaita used these DNA force gauges to provide the first direct evidence for the mechanical forces of T cells, the security guards of the immune system. His lab showed how T cells use a kind of mechanical “handshake” or tug to test whether a cell they encounter is a friend or foe. These mechanical tugs are central to a T cell’s decision for whether to mount an immune response.

“Your blood contains millions of different types of T cells, and each T cell is evolved to detect a certain pathogen or foreign agent,” Salaita explains. “T cells are constantly sampling cells throughout your body using these mechanical tugs. They bind and pull on proteins on a cell’s surface and, if the bond is strong, that’s a signal that the T cell has found a foreign agent.”

Salaita’s lab built on this discovery in a paper recently published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). Work led by Emory chemistry graduate student Rong Ma refined the sensitivity of the DNA force gauges. Not only can they detect these mechanical tugs at a force so slight that it is nearly one-billionth the weight of a paperclip, they can also capture evidence of tugs as brief as the blink of an eye.

The research provides an unprecedented look at the mechanical forces involved in the immune system. “We showed that, in addition to being evolved to detect certain foreign agents, T cells will also apply very brief mechanical tugs to foreign agents that are a near match,” Salaita says. “The frequency and duration of the tug depends on how closely the foreign agent is matched to the T cell receptor.”

The result provides a tool to predict how strong of an immune response a T cell will mount. “We hope this tool may eventually be used to fine tune immunotherapies for individual cancer patients,” Salaita says. “It could potentially help engineer T cells to go after particular cancer cells.”

Related:

Nano-walkers take speedy leap forward with first rolling DNA-based motor

T cells use 'handshakes' to sort friends from foes

New methods reveal the mechanics of blood clotting

Chemists reveal the force within you

from eScienceCommons https://ift.tt/2O9bEcO