Satellite image of a pumice raft floating near the Kingdom of Tonga. Image via NASA Earth Observatory.

In early August 2019, an unnamed volcano in the South Pacific Ocean near the Kingdom of Tonga erupted roughly 130 feet (40 meters) underwater. As lava spewed from the volcano, it cooled into pumice — porous rock filled with gas bubbles — and floated to the surface. This volcanic debris, with some fragments tiny and some as large as beach balls, aggregated into pumice rafts spanning an area of about 60 square miles (200 square km) — almost as big as Washington, D.C.

These temporary islands of volcanic rock are shaped and moved by ocean currents, wind, and waves, and provide a literal toehold for marine life, such as barnacles, coral, seaweed and mollusks, say scientists.

Several sailing crews have encountered the rocks. In a video, below, posted on YouTube on August 17, Shannon Lenz said:

On August 9, 2019, we sailed through a pumice field for 6-8 hours, much of the time there was no visible water. It was like plowing through a field. We figured the pumice was at least 6-inches thick.

An Australian couple, Michael Hoult and Larissa Brill, were sailing a catamaran to Fiji, when they encountered the raft on August 16. The couple said in a Facebook post:

We entered a total rock rubble slick made up of pumice stones from marble to basketball size.

Pumice rafts aren’t that common, according to Martin Jutzeler, a volcanologist at the University of Tasmania in Hobart. He told EOS:

We see about two per decade.

Jutzeler told EOS that not all undersea eruptions produce them, but the rafts that do form tend to stick around. They can last for months or years until the pumice abrades itself into dust or finally sinks. And floating pumice can traverse long distances. For example, he said, when the same unnamed volcano near Tonga erupted in 2001, the pumice raft it created eventually arrived in Queensland, Australia.

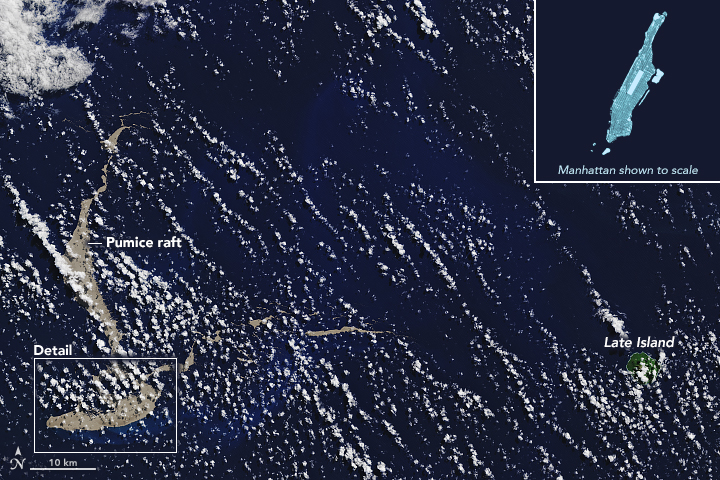

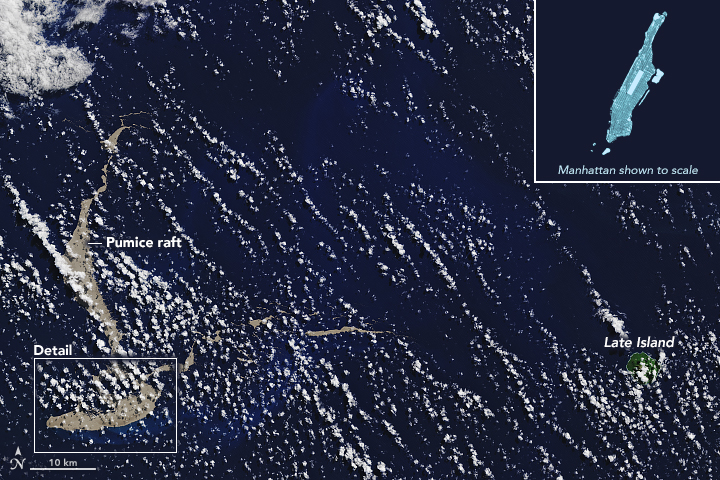

August 13, 2109. See detail below. Image via NASA Earth Observatory.

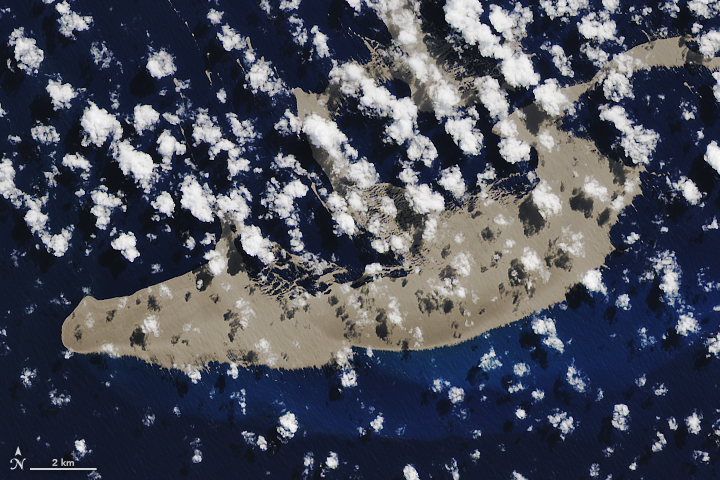

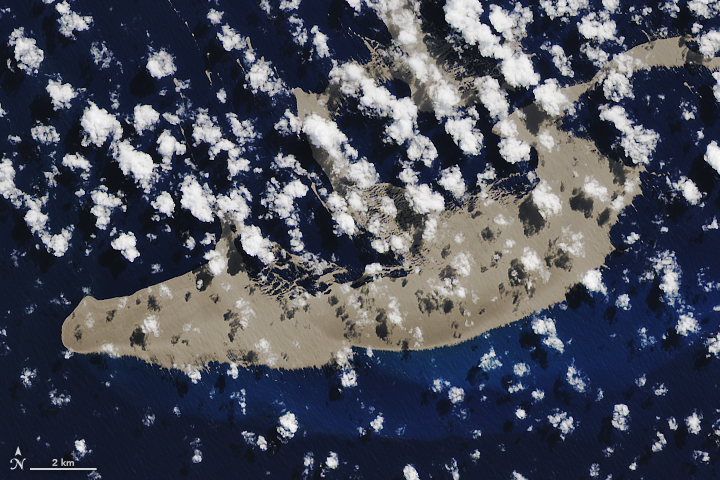

Detail of above image, taken August 13, 2109. Image via NASA Earth Observatory.

These transient, movable islands play an important role in marine ecosystems, scientists say, moving barnacles, coral, and seaweed that cling to the pumice to new homes. Some news outlets are reporting that the pumice might make it to Australia to help restore the Great Barrier Reef’s corals , half of which have been killed in recent years as a result of climate change. According to Denison University volcanologist Erik Klemetti, the long-distance journeys of pumice rafts are

… definitely a way to get organisms to disperse widely.

But the idea that the stowaways aboard pumice rafts might replenish the Great Barrier Reef’s corals is wishful thinking, Klemetti told EOS. He said:

That’s probably an oversell.

Researchers are keeping a close watch on how the rafts are moving. Satellite imagery provides nearly daily updates. Ocean currents, wind, and waves sculpt and power the rafts, which now number in the hundreds.

A raft of rock, the size of 20,000 football fields is floating towards Queensland. The pumice was created when an underwater volcano erupted off Tonga. Scientists say it'll bring millions of new coral to the Great Barrier Reef. @ErinEdwards7 @QUT #7NEWS pic.twitter.com/W7pKdowYw2

— 7NEWS Gold Coast (@7NewsGoldCoast) August 24, 2019

Bottom line: In August 2019, rafts of pumice, spewed from an undersea volcano and spanning an area about the size of Washington, D.C., appeared in the South Pacific.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/31x2RFi

Satellite image of a pumice raft floating near the Kingdom of Tonga. Image via NASA Earth Observatory.

In early August 2019, an unnamed volcano in the South Pacific Ocean near the Kingdom of Tonga erupted roughly 130 feet (40 meters) underwater. As lava spewed from the volcano, it cooled into pumice — porous rock filled with gas bubbles — and floated to the surface. This volcanic debris, with some fragments tiny and some as large as beach balls, aggregated into pumice rafts spanning an area of about 60 square miles (200 square km) — almost as big as Washington, D.C.

These temporary islands of volcanic rock are shaped and moved by ocean currents, wind, and waves, and provide a literal toehold for marine life, such as barnacles, coral, seaweed and mollusks, say scientists.

Several sailing crews have encountered the rocks. In a video, below, posted on YouTube on August 17, Shannon Lenz said:

On August 9, 2019, we sailed through a pumice field for 6-8 hours, much of the time there was no visible water. It was like plowing through a field. We figured the pumice was at least 6-inches thick.

An Australian couple, Michael Hoult and Larissa Brill, were sailing a catamaran to Fiji, when they encountered the raft on August 16. The couple said in a Facebook post:

We entered a total rock rubble slick made up of pumice stones from marble to basketball size.

Pumice rafts aren’t that common, according to Martin Jutzeler, a volcanologist at the University of Tasmania in Hobart. He told EOS:

We see about two per decade.

Jutzeler told EOS that not all undersea eruptions produce them, but the rafts that do form tend to stick around. They can last for months or years until the pumice abrades itself into dust or finally sinks. And floating pumice can traverse long distances. For example, he said, when the same unnamed volcano near Tonga erupted in 2001, the pumice raft it created eventually arrived in Queensland, Australia.

August 13, 2109. See detail below. Image via NASA Earth Observatory.

Detail of above image, taken August 13, 2109. Image via NASA Earth Observatory.

These transient, movable islands play an important role in marine ecosystems, scientists say, moving barnacles, coral, and seaweed that cling to the pumice to new homes. Some news outlets are reporting that the pumice might make it to Australia to help restore the Great Barrier Reef’s corals , half of which have been killed in recent years as a result of climate change. According to Denison University volcanologist Erik Klemetti, the long-distance journeys of pumice rafts are

… definitely a way to get organisms to disperse widely.

But the idea that the stowaways aboard pumice rafts might replenish the Great Barrier Reef’s corals is wishful thinking, Klemetti told EOS. He said:

That’s probably an oversell.

Researchers are keeping a close watch on how the rafts are moving. Satellite imagery provides nearly daily updates. Ocean currents, wind, and waves sculpt and power the rafts, which now number in the hundreds.

A raft of rock, the size of 20,000 football fields is floating towards Queensland. The pumice was created when an underwater volcano erupted off Tonga. Scientists say it'll bring millions of new coral to the Great Barrier Reef. @ErinEdwards7 @QUT #7NEWS pic.twitter.com/W7pKdowYw2

— 7NEWS Gold Coast (@7NewsGoldCoast) August 24, 2019

Bottom line: In August 2019, rafts of pumice, spewed from an undersea volcano and spanning an area about the size of Washington, D.C., appeared in the South Pacific.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/31x2RFi

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire