The months around February are perfect for both Northern Hemisphere and Southern Hemisphere observers to view the brightest star in the sky: Sirius. But this star is shifting inexorably westward each night, as Earth orbits our sun and our perspective on the galaxy undergoes its subtle, continual change. By early April, Sirius will be moving noticeably toward the sunset glare. See it now. It’s the legendary Dog Star, part of the constellation Canis Major the Greater Dog.

From the Northern Hemisphere now, you’ll find Sirius arcing across in the southern sky in the evening. From the Southern Hemisphere, you’ll find it swinging high overhead at that time of night.

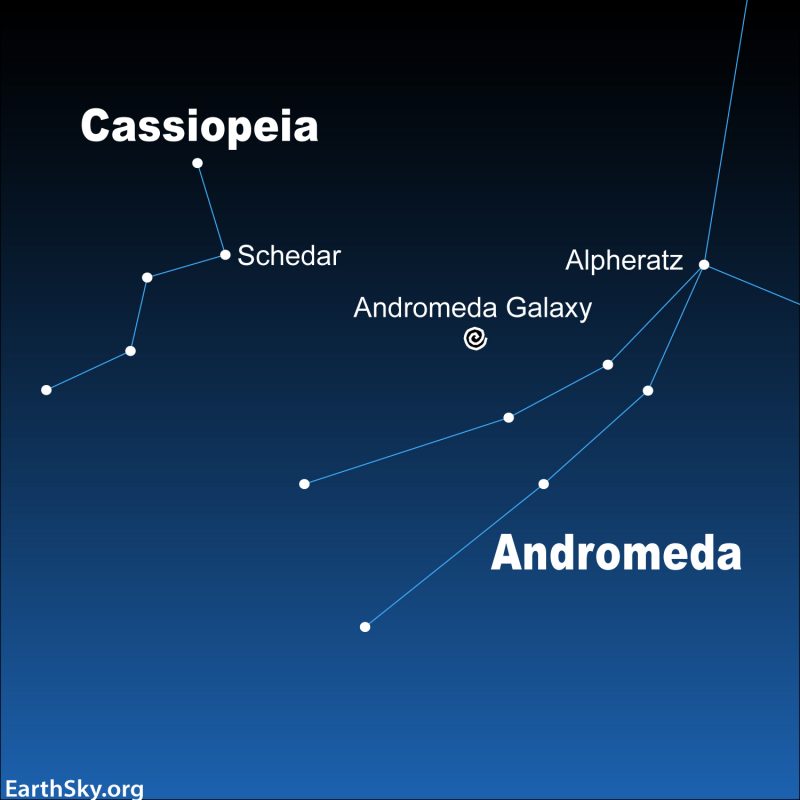

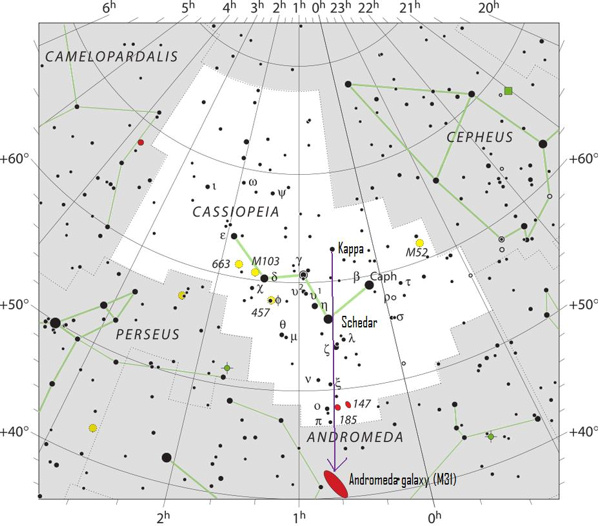

It’s always easy to spot as the brightest point of light in its region of sky … unless a planet happens to be near it, like Jupiter is in 2026. Not sure which object is Sirius and which is bright Jupiter? You’ll always know if you notice that the three Belt stars of Orion always point to Sirius. See the photo above.

It’s a flashy rainbow star

Although white to blue-white in color, Sirius might be called a rainbow star, as it often flickers with many colors. The flickering colors are especially easy to notice when you spot Sirius low in the sky.

The brightness, twinkling and color changes sometimes prompt people to report Sirius as a UFO!

In fact, these changes are simply what happens when such a bright star as Sirius shines through the blanket of Earth’s atmosphere. The varying density and temperature of Earth’s air affect starlight, especially when we’re seeing the star low in the sky.

The shimmering and color changes happen for other stars, too, but these effects are more noticeable for Sirius because Sirius is so bright.

Finding Sirius

From the mid-northern latitudes such as most of the U.S., Sirius rises in the southeast, arcs across the southern sky, and sets in the southwest. From the Southern Hemisphere, Sirius arcs high overhead.

As seen from around the world, Sirius rises in mid-evening in December. By mid-April, Sirius is setting in the southwest in mid-evening.

Sirius is always easy to find. It’s the sky’s brightest star! Plus, anyone familiar with the constellation Orion can simply draw a line through Orion’s Belt to find this star. Sirius is roughly eight times as far from the Belt as the Belt is wide.

The mythology of Sirius

Sirius is well known as the Dog Star, because it’s the chief star in the constellation Canis Major the Greater Dog. Have you ever heard anyone speak of the dog days of summer? Sirius is behind the sun as seen from Earth in Northern Hemisphere summer. In late summer, it appears in the east before sunrise, near the sun in our sky. The early stargazers might have imagined the double-whammy of Sirius and the sun caused the hot weather, or dog days.

In ancient Egypt, the name Sirius signified its nature as scorching or sparkling. The star was associated with the Egyptian gods Osiris, Sopdet and other gods. Ancient Egyptians noted that Sirius rose just before the sun each year immediately prior to the annual flooding of the Nile River. Although the floods could bring destruction, they also brought new soil and new life.

Osiris was an Egyptian god of life, death, fertility and rebirth of plant life along the Nile. Sopdet – who might have an even closer association with the star Sirius – began as an agricultural deity in Egypt, also closely associated with the Nile. The Egyptian new year celebration was a festival known as the Coming of Sopdet.

More mythology of the Dog Star

In India, Sirius is sometimes known as Svana, the dog of Prince Yudhisthira. The prince and his four brothers, along with Svana, set out on a long and arduous journey to find the kingdom of heaven. However, one by one the brothers all abandoned the search until only Yudhisthira and his dog, Svana, remained. At long last they came to the gates of heaven. The gatekeeper, Indra, welcomed the prince but denied Svana entrance.

Yudhisthira was aghast and told Indra that he could not forsake his good and faithful servant and friend. His brothers, Yudhisthira said, had abandoned the journey to heaven to follow their hearts’ desires. But Svana, who had given his heart freely, chose to follow none but Yudhisthira. The prince said that, without his dog, he would forsake even heaven. This is what Indra had wanted to hear, and then he welcomed both the prince and the dog through the gates of heaven.

The brightest star

Astronomers express the brightness of stars in terms of stellar magnitude. The smaller the number, the brighter the star.

The visual magnitude of Sirius is -1.44, lower – brighter – than any other star. There are brighter stars than Sirius in terms of actual energy and light output, but they are farther away and hence appear dimmer.

Normally, the only objects that outshine Sirius in our heavens are the sun, moon, Venus, Jupiter, Mars and Mercury (and usually Sirius outshines Mercury, too).

Not counting the sun, the second-brightest star in all of Earth’s sky – next-brightest after Sirius – is Canopus. It is visible from latitudes like those of the southern U.S.

The third-brightest and, as it happens, the closest major star to our sun is Alpha Centauri. However, it’s too far south in the sky to see easily from mid-northern latitudes.

The science of Sirius

At 8.6 light-years distance, Sirius is one of the nearest stars to us after the sun. By the way, a light year is nearly 6 trillion miles (9.6 trillion km)!

Sirius is classified by astronomers as an A type star. That means it’s a much hotter star than our sun; its surface temperature is about 17,000 degrees Fahrenheit (9,400 Celsius) in contrast to our sun’s 10,000 F (5,500 C). With slightly more than twice the mass of the sun and just less than twice its diameter, Sirius still puts out 26 times as much energy. It’s a main-sequence star, meaning it produces most of its energy by converting hydrogen into helium through nuclear fusion.

And Sirius has a companion star

Sirius has a small, faint companion star appropriately called Sirius B or the Pup. That name signifies youth, but in fact the companion to Sirius is a white dwarf, a dead star. Once a mighty star, the Pup today is an Earth-sized ember, too faint to be seen without a telescope.

The position of Sirius is RA: 06h 45m 08.9s, dec: -16° 42′ 58″.

Bottom line: Sirius is the brightest star in the night sky as seen from Earth and is visible from both hemispheres. And it lies just 8.6 light-years away in the constellation Canis Major the Greater Dog.

The post See Sirius, the brightest star in the night sky first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/jaxAyEW

The months around February are perfect for both Northern Hemisphere and Southern Hemisphere observers to view the brightest star in the sky: Sirius. But this star is shifting inexorably westward each night, as Earth orbits our sun and our perspective on the galaxy undergoes its subtle, continual change. By early April, Sirius will be moving noticeably toward the sunset glare. See it now. It’s the legendary Dog Star, part of the constellation Canis Major the Greater Dog.

From the Northern Hemisphere now, you’ll find Sirius arcing across in the southern sky in the evening. From the Southern Hemisphere, you’ll find it swinging high overhead at that time of night.

It’s always easy to spot as the brightest point of light in its region of sky … unless a planet happens to be near it, like Jupiter is in 2026. Not sure which object is Sirius and which is bright Jupiter? You’ll always know if you notice that the three Belt stars of Orion always point to Sirius. See the photo above.

It’s a flashy rainbow star

Although white to blue-white in color, Sirius might be called a rainbow star, as it often flickers with many colors. The flickering colors are especially easy to notice when you spot Sirius low in the sky.

The brightness, twinkling and color changes sometimes prompt people to report Sirius as a UFO!

In fact, these changes are simply what happens when such a bright star as Sirius shines through the blanket of Earth’s atmosphere. The varying density and temperature of Earth’s air affect starlight, especially when we’re seeing the star low in the sky.

The shimmering and color changes happen for other stars, too, but these effects are more noticeable for Sirius because Sirius is so bright.

Finding Sirius

From the mid-northern latitudes such as most of the U.S., Sirius rises in the southeast, arcs across the southern sky, and sets in the southwest. From the Southern Hemisphere, Sirius arcs high overhead.

As seen from around the world, Sirius rises in mid-evening in December. By mid-April, Sirius is setting in the southwest in mid-evening.

Sirius is always easy to find. It’s the sky’s brightest star! Plus, anyone familiar with the constellation Orion can simply draw a line through Orion’s Belt to find this star. Sirius is roughly eight times as far from the Belt as the Belt is wide.

The mythology of Sirius

Sirius is well known as the Dog Star, because it’s the chief star in the constellation Canis Major the Greater Dog. Have you ever heard anyone speak of the dog days of summer? Sirius is behind the sun as seen from Earth in Northern Hemisphere summer. In late summer, it appears in the east before sunrise, near the sun in our sky. The early stargazers might have imagined the double-whammy of Sirius and the sun caused the hot weather, or dog days.

In ancient Egypt, the name Sirius signified its nature as scorching or sparkling. The star was associated with the Egyptian gods Osiris, Sopdet and other gods. Ancient Egyptians noted that Sirius rose just before the sun each year immediately prior to the annual flooding of the Nile River. Although the floods could bring destruction, they also brought new soil and new life.

Osiris was an Egyptian god of life, death, fertility and rebirth of plant life along the Nile. Sopdet – who might have an even closer association with the star Sirius – began as an agricultural deity in Egypt, also closely associated with the Nile. The Egyptian new year celebration was a festival known as the Coming of Sopdet.

More mythology of the Dog Star

In India, Sirius is sometimes known as Svana, the dog of Prince Yudhisthira. The prince and his four brothers, along with Svana, set out on a long and arduous journey to find the kingdom of heaven. However, one by one the brothers all abandoned the search until only Yudhisthira and his dog, Svana, remained. At long last they came to the gates of heaven. The gatekeeper, Indra, welcomed the prince but denied Svana entrance.

Yudhisthira was aghast and told Indra that he could not forsake his good and faithful servant and friend. His brothers, Yudhisthira said, had abandoned the journey to heaven to follow their hearts’ desires. But Svana, who had given his heart freely, chose to follow none but Yudhisthira. The prince said that, without his dog, he would forsake even heaven. This is what Indra had wanted to hear, and then he welcomed both the prince and the dog through the gates of heaven.

The brightest star

Astronomers express the brightness of stars in terms of stellar magnitude. The smaller the number, the brighter the star.

The visual magnitude of Sirius is -1.44, lower – brighter – than any other star. There are brighter stars than Sirius in terms of actual energy and light output, but they are farther away and hence appear dimmer.

Normally, the only objects that outshine Sirius in our heavens are the sun, moon, Venus, Jupiter, Mars and Mercury (and usually Sirius outshines Mercury, too).

Not counting the sun, the second-brightest star in all of Earth’s sky – next-brightest after Sirius – is Canopus. It is visible from latitudes like those of the southern U.S.

The third-brightest and, as it happens, the closest major star to our sun is Alpha Centauri. However, it’s too far south in the sky to see easily from mid-northern latitudes.

The science of Sirius

At 8.6 light-years distance, Sirius is one of the nearest stars to us after the sun. By the way, a light year is nearly 6 trillion miles (9.6 trillion km)!

Sirius is classified by astronomers as an A type star. That means it’s a much hotter star than our sun; its surface temperature is about 17,000 degrees Fahrenheit (9,400 Celsius) in contrast to our sun’s 10,000 F (5,500 C). With slightly more than twice the mass of the sun and just less than twice its diameter, Sirius still puts out 26 times as much energy. It’s a main-sequence star, meaning it produces most of its energy by converting hydrogen into helium through nuclear fusion.

And Sirius has a companion star

Sirius has a small, faint companion star appropriately called Sirius B or the Pup. That name signifies youth, but in fact the companion to Sirius is a white dwarf, a dead star. Once a mighty star, the Pup today is an Earth-sized ember, too faint to be seen without a telescope.

The position of Sirius is RA: 06h 45m 08.9s, dec: -16° 42′ 58″.

Bottom line: Sirius is the brightest star in the night sky as seen from Earth and is visible from both hemispheres. And it lies just 8.6 light-years away in the constellation Canis Major the Greater Dog.

The post See Sirius, the brightest star in the night sky first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/jaxAyEW