EarthSky’s 2026 lunar calendar shows the moon phase for every day of the year. Get yours today!

By Chloe Griffin and Thomas Gernon, University of Southampton

Ice-free oases on Snowball Earth sheltered early life

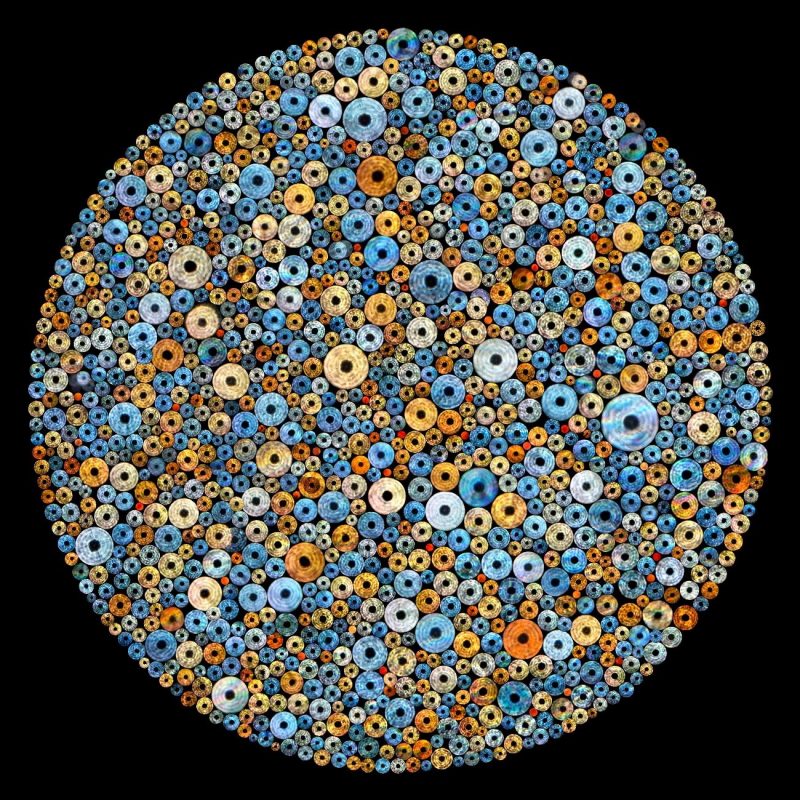

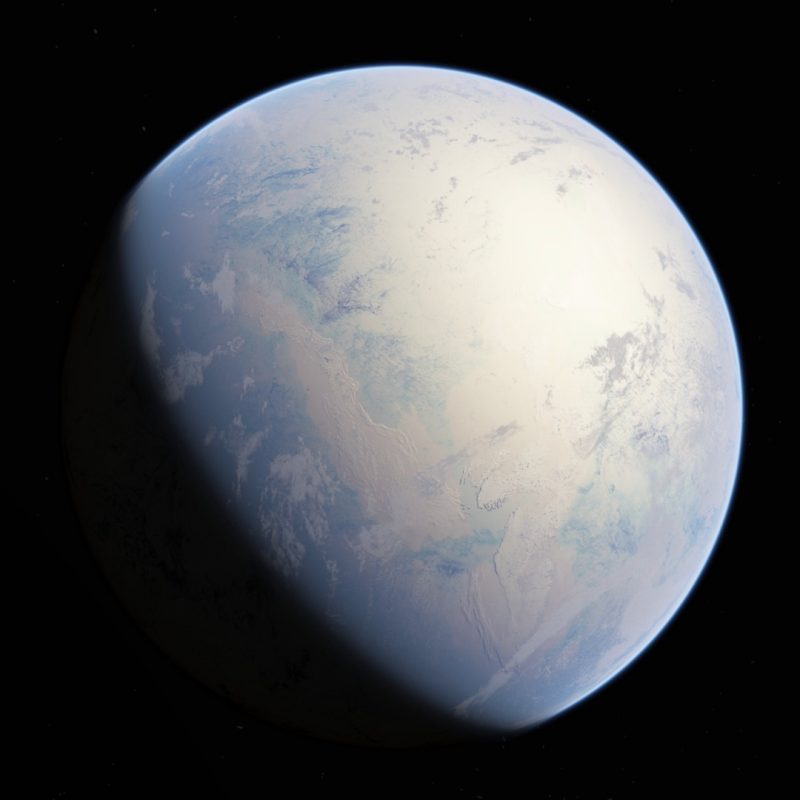

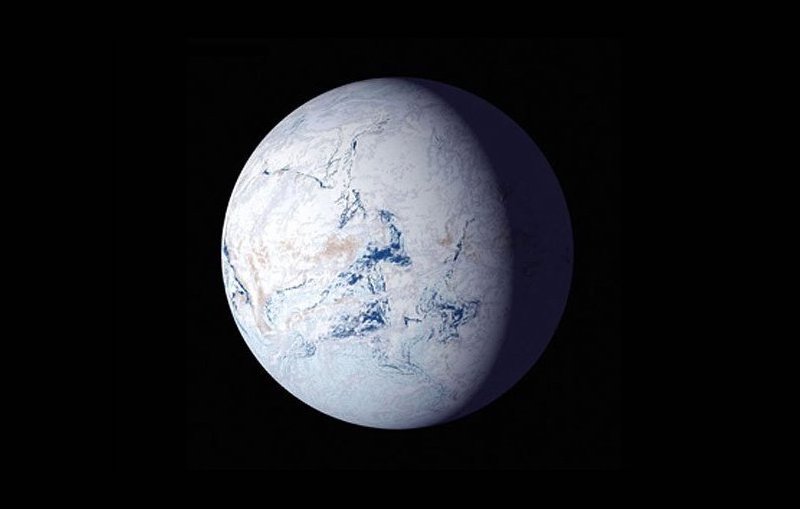

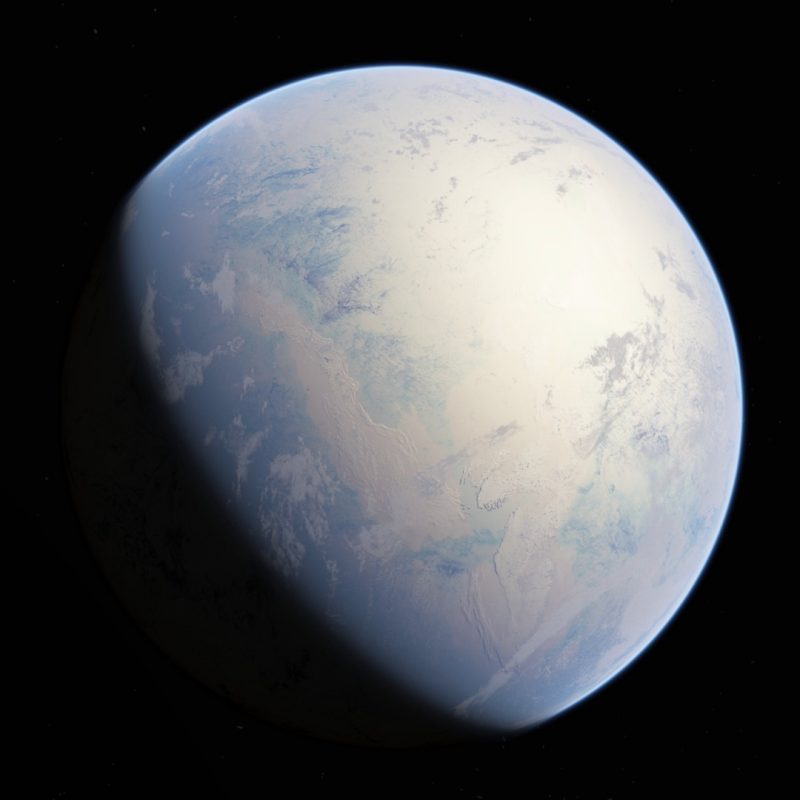

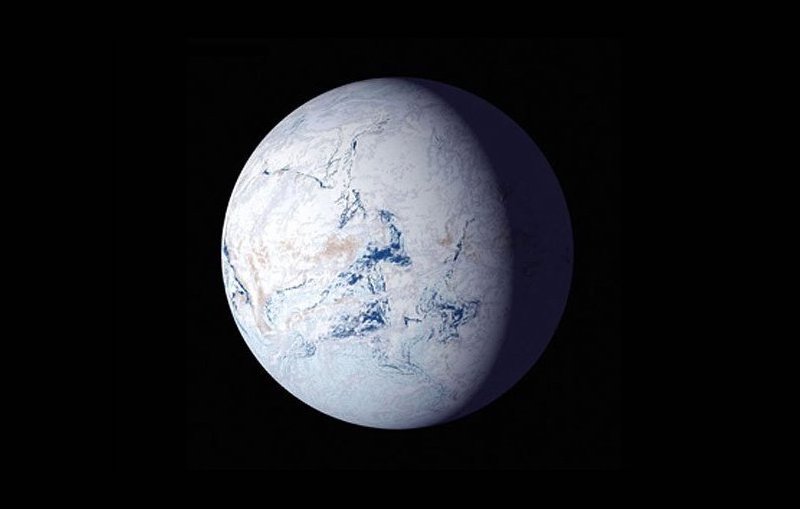

To an astronaut today, the Earth looks like a vibrant blue marble from space. But 700 million years ago, it would have looked like a blinding white snowball. This seems an unlikely cradle for life. Yet new evidence suggests the frozen ocean featured ice-free oases, providing a lifeline for our earliest complex ancestors.

During the Cryogenian period, from 720 million to 635 million years ago, massive ice sheets covered Earth from the poles to the tropics. Surface temperatures were as low as -50° C (-58° F).

Because the bright white surface of the planet reflected (rather than absorbed) the sun’s energy – a phenomenon known as the albedo effect – the Earth remained locked in this extreme climate state, dubbed “Snowball Earth,” for tens of millions of years.

Scientists have long thought that when the ocean is sealed under a kilometer-thick (.6 mile) shell of ice, the usual connection between the atmosphere and oceans would be prevented, muting climate variability. That is, normal short-term variations in temperature, precipitation, or wind patterns would be limited.

However, our new research, published in Earth and Planetary Science Letters, challenges this status quo. By forensically decoding ancient rocks, we’ve discovered that the climate became briefly more dynamic than normally expected on Snowball Earth. In fact, it even oscillated to a rhythm strikingly like our own today.

Decoding climate cycles on Snowball Earth

The breakthrough came from the Garvellach Islands off the west coast of Scotland. These rocks formed during the Sturtian glaciation (720–660 million years ago), the first of two Snowball Earth events. The second was the Marinoan (650–635 million years ago). The Scottish islands contain a unique, exquisitely preserved archive of Snowball Earth, locking in the secrets of this weird ancient world.

Specifically, laminated sedimentary rocks, or varves, act as natural data loggers. Picture a lake today: sediment settles quietly through the water column and on to the lake bed. Over time, these layers of sediment build up at the bottom of the lake. Thousands or millions of years later, geologists can use the physical, chemical and biological information trapped in the now ancient lake sediments to track how environmental conditions – including climatic ones – changed over time.

While modern sediments like this are easy to find, detailed climate archives from deep time are vanishingly rare. That has left us in the dark about how our planet’s climate behaved during Snowball Earth … until now.

The new study

We investigated a unique pile of rocks six meters (20 feet) thick, containing around 2,600 such varves, on the Garvellach Islands. What they revealed was, quite frankly, jaw-dropping. Microscopic and statistical analysis showed that these layers weren’t uniform, as you might expect locked in a Snowball state.

Instead, they conform to predictable cycles occurring over timescales of a few years to centuries. Perhaps yet more surprising is that almost the full suite of climate rhythms we know from today are preserved; from annual seasons to modern phenomena like El Niño (a climate pattern of warming sea surface temperatures in parts of the Pacific Ocean), and longer-term cycles linked to solar activity lasting decades to centuries.

We certainly wouldn’t have expected El Niño cycles, which happen every two to seven years today. This requires a seamless communication between the atmosphere and oceans, which is hard to envision on an ice-covered world.

A (partially) ice-free ocean?

The cycles in these ancient sediments do raise an intriguing possibility: could parts of the ocean have been ice-free during Snowball Earth?

To get to the bottom of this, we used computer climate simulations to test different climate scenarios. Put simply, that means seeing how changing the amount of ice on the oceans changes the patterns of surface temperature across the globe. We found that when the ocean was frozen completely solid, climate oscillations were largely suppressed.

Our simulations also showed that vast areas of open water weren’t needed to restart these oscillations; if just a small fraction of the ocean surface was ice free – say, 15% or so – atmosphere ocean interactions could have resumed.

Comparing the simulated climate records to the patterns we decoded in the rock record, we think these sediments most likely document a patch of open water in the tropics, sometimes called an oasis. Many scientists use such oases to reconcile the survival of life with the near-global glaciation.

Interestingly, several other lines of evidence suggest a partially ice-free ocean at roughly the same time. So, could our rocks provide evidence for temporary warming during Snowball Earth?

While they confirm temporary patches of warmth in the surface ocean, these rocks represent a snapshot of around 3,000 years in a multi-million-year glaciation; that is, likely a fleeting “Slushball” state within an otherwise frozen world. Another recent study even argues that liquid water could have persisted at 5° F (-15° C), but only if it were extremely salty.

Oases for life?

Crucially though, our new analysis shows that the climate system has an inherent tendency to oscillate, even under the most extreme conditions. Could these oases in the sea have been life-rafts for the earliest complex animals?

Perhaps the biggest paradox of Snowball Earth is that this hostile deep-freeze triggered a biological revolution. Around this time, the diversity and abundance of multicellular life exploded. Phosphorus-rich dust ground up by the very glaciers that threatened to extinguish it fuelled this event. Scientists think this happened during the warm interval between the two Snowball glaciations.

But for life to thrive after the ice, it first had to survive the second (Marinoan) glaciation. Our study offers a viable solution to this puzzle: if tropical oceans weren’t entirely frozen over, but held pockets of open water, these oases would have acted as habitable refuges.

Rather than a planet frozen solid, our work paints a picture of an “oscillating” world where thin cracks in the ice or more expansive patches of open water formed habitats that allowed – even encouraged – the colonization of life.

By maintaining biodiversity during Earth’s most extreme ice age, these oases ensured that when the ice finally melted away, life was ready to bloom into the complex ecosystems we see today, eventually leading to us.

Chloe Griffin, Research Fellow, School of Ocean & Earth Science, and Thomas Gernon, Professor in Earth & Climate Science, University of Southampton.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Bottom line: Scientists have found evidence for ice-free oases on Snowball Earth, which might have provided a lifeline for early complex life.

Read more: Enormous glaciers on Snowball Earth helped life evolve

The post Ice-free oases on Snowball Earth sheltered early life first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/IgSrNAs

EarthSky’s 2026 lunar calendar shows the moon phase for every day of the year. Get yours today!

By Chloe Griffin and Thomas Gernon, University of Southampton

Ice-free oases on Snowball Earth sheltered early life

To an astronaut today, the Earth looks like a vibrant blue marble from space. But 700 million years ago, it would have looked like a blinding white snowball. This seems an unlikely cradle for life. Yet new evidence suggests the frozen ocean featured ice-free oases, providing a lifeline for our earliest complex ancestors.

During the Cryogenian period, from 720 million to 635 million years ago, massive ice sheets covered Earth from the poles to the tropics. Surface temperatures were as low as -50° C (-58° F).

Because the bright white surface of the planet reflected (rather than absorbed) the sun’s energy – a phenomenon known as the albedo effect – the Earth remained locked in this extreme climate state, dubbed “Snowball Earth,” for tens of millions of years.

Scientists have long thought that when the ocean is sealed under a kilometer-thick (.6 mile) shell of ice, the usual connection between the atmosphere and oceans would be prevented, muting climate variability. That is, normal short-term variations in temperature, precipitation, or wind patterns would be limited.

However, our new research, published in Earth and Planetary Science Letters, challenges this status quo. By forensically decoding ancient rocks, we’ve discovered that the climate became briefly more dynamic than normally expected on Snowball Earth. In fact, it even oscillated to a rhythm strikingly like our own today.

Decoding climate cycles on Snowball Earth

The breakthrough came from the Garvellach Islands off the west coast of Scotland. These rocks formed during the Sturtian glaciation (720–660 million years ago), the first of two Snowball Earth events. The second was the Marinoan (650–635 million years ago). The Scottish islands contain a unique, exquisitely preserved archive of Snowball Earth, locking in the secrets of this weird ancient world.

Specifically, laminated sedimentary rocks, or varves, act as natural data loggers. Picture a lake today: sediment settles quietly through the water column and on to the lake bed. Over time, these layers of sediment build up at the bottom of the lake. Thousands or millions of years later, geologists can use the physical, chemical and biological information trapped in the now ancient lake sediments to track how environmental conditions – including climatic ones – changed over time.

While modern sediments like this are easy to find, detailed climate archives from deep time are vanishingly rare. That has left us in the dark about how our planet’s climate behaved during Snowball Earth … until now.

The new study

We investigated a unique pile of rocks six meters (20 feet) thick, containing around 2,600 such varves, on the Garvellach Islands. What they revealed was, quite frankly, jaw-dropping. Microscopic and statistical analysis showed that these layers weren’t uniform, as you might expect locked in a Snowball state.

Instead, they conform to predictable cycles occurring over timescales of a few years to centuries. Perhaps yet more surprising is that almost the full suite of climate rhythms we know from today are preserved; from annual seasons to modern phenomena like El Niño (a climate pattern of warming sea surface temperatures in parts of the Pacific Ocean), and longer-term cycles linked to solar activity lasting decades to centuries.

We certainly wouldn’t have expected El Niño cycles, which happen every two to seven years today. This requires a seamless communication between the atmosphere and oceans, which is hard to envision on an ice-covered world.

A (partially) ice-free ocean?

The cycles in these ancient sediments do raise an intriguing possibility: could parts of the ocean have been ice-free during Snowball Earth?

To get to the bottom of this, we used computer climate simulations to test different climate scenarios. Put simply, that means seeing how changing the amount of ice on the oceans changes the patterns of surface temperature across the globe. We found that when the ocean was frozen completely solid, climate oscillations were largely suppressed.

Our simulations also showed that vast areas of open water weren’t needed to restart these oscillations; if just a small fraction of the ocean surface was ice free – say, 15% or so – atmosphere ocean interactions could have resumed.

Comparing the simulated climate records to the patterns we decoded in the rock record, we think these sediments most likely document a patch of open water in the tropics, sometimes called an oasis. Many scientists use such oases to reconcile the survival of life with the near-global glaciation.

Interestingly, several other lines of evidence suggest a partially ice-free ocean at roughly the same time. So, could our rocks provide evidence for temporary warming during Snowball Earth?

While they confirm temporary patches of warmth in the surface ocean, these rocks represent a snapshot of around 3,000 years in a multi-million-year glaciation; that is, likely a fleeting “Slushball” state within an otherwise frozen world. Another recent study even argues that liquid water could have persisted at 5° F (-15° C), but only if it were extremely salty.

Oases for life?

Crucially though, our new analysis shows that the climate system has an inherent tendency to oscillate, even under the most extreme conditions. Could these oases in the sea have been life-rafts for the earliest complex animals?

Perhaps the biggest paradox of Snowball Earth is that this hostile deep-freeze triggered a biological revolution. Around this time, the diversity and abundance of multicellular life exploded. Phosphorus-rich dust ground up by the very glaciers that threatened to extinguish it fuelled this event. Scientists think this happened during the warm interval between the two Snowball glaciations.

But for life to thrive after the ice, it first had to survive the second (Marinoan) glaciation. Our study offers a viable solution to this puzzle: if tropical oceans weren’t entirely frozen over, but held pockets of open water, these oases would have acted as habitable refuges.

Rather than a planet frozen solid, our work paints a picture of an “oscillating” world where thin cracks in the ice or more expansive patches of open water formed habitats that allowed – even encouraged – the colonization of life.

By maintaining biodiversity during Earth’s most extreme ice age, these oases ensured that when the ice finally melted away, life was ready to bloom into the complex ecosystems we see today, eventually leading to us.

Chloe Griffin, Research Fellow, School of Ocean & Earth Science, and Thomas Gernon, Professor in Earth & Climate Science, University of Southampton.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Bottom line: Scientists have found evidence for ice-free oases on Snowball Earth, which might have provided a lifeline for early complex life.

Read more: Enormous glaciers on Snowball Earth helped life evolve

The post Ice-free oases on Snowball Earth sheltered early life first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/IgSrNAs