Big Dipper in autumn

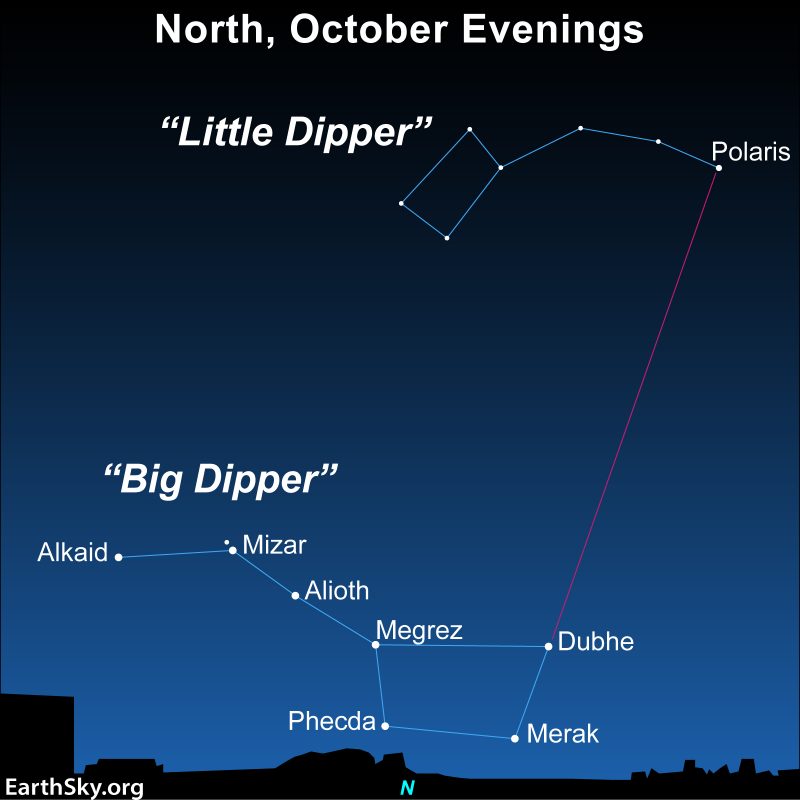

It’s autumn for those of us in the Northern Hemisphere. There’s a chill in the air, and nights are getting long. Maybe you’ve been standing outside on an autumn evening, looking for the Big Dipper? It’s perhaps the most famous of all star patterns. You know you’re supposed to look northward. And you’re looking, but you can’t find it. Why not?

If you’re at a latitude of about 41 degrees north – or farther north – you will see the Dipper. From very northerly latitudes, the Big Dipper is circumpolar, or always above the northern horizon. If you’re below that latitude, though, you won’t find the Big Dipper in the evening now. In autumn, the Big Dipper is below your horizon during the evening hours.

Want to see it? If you’re in the southern U.S. or a comparable latitude, you’ll have to wait until the hours before dawn. At this time of the year, before dawn, you’ll easily see the Big Dipper ascending in the northeast.

To remember the best times to view the Big Dipper in the evening, remember the phrase: spring up and fall down. That’s because the Big Dipper shines way up high in the sky on spring evenings but close to the horizon on autumn evenings.

5 Dipper stars are related

So you might or might not be able to see the Big Dipper now. But you can think about it. Did you know that the distances of the stars in the Dipper reveal something interesting about them? Five of these seven stars have a physical relationship in space. That’s not always true of patterns on our sky’s dome. Most star patterns are made up of unrelated stars at vastly different distances.

Five of the Dipper’s stars – Merak, Mizar, Alioth, Megrez and Phecda – are part of a single star grouping. They probably were born together from a single cloud of gas and dust, and they’re still moving together as a family.

The other two stars in the Dipper – Dubhe and Alkaid – are unrelated to each other and to the other five. Here are the star distances to the Dipper’s stars:

Alkaid 101 light-years

Mizar 83 light-years

Alioth 81 light-years

Megrez 59 light-years

Phecda 83 light-years

Dubhe 123 light-years

Merak 80 light-years

What’s more, Dubhe and Alkaid are moving in an entirely different direction from the other five stars.

How the Big Dipper changes over time

And that’s why – millions of years from now – the Big Dipper will have lost its familiar dipper-like shape.

They do change, Here is a gif oh the big dipper changing over time pic.twitter.com/nwezuQnYyR

— LetsDoIt291 (@_lets_do_it_) June 24, 2018

Images of the Big Dipper

Bottom line: If you’re above 41 degrees north latitude, the Big Dipper star pattern is circumpolar; it stays in your sky always, circling around the northern pole star, Polaris. Below that latitude, the Dipper is below your horizon in the evening in autumn.

The post The Big Dipper: Why can’t you see it now? first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/AQI35Cm

Big Dipper in autumn

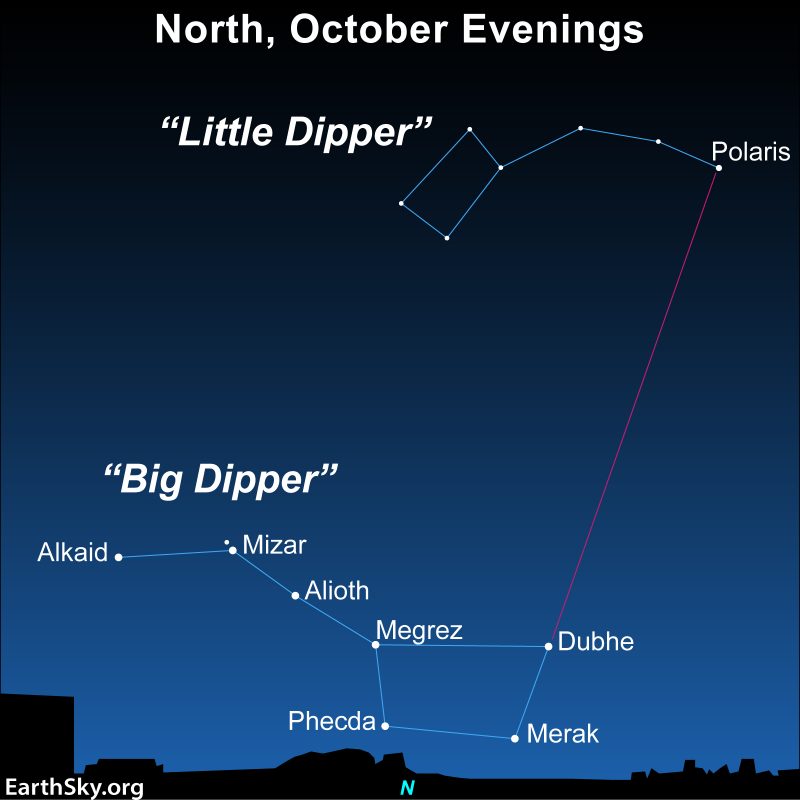

It’s autumn for those of us in the Northern Hemisphere. There’s a chill in the air, and nights are getting long. Maybe you’ve been standing outside on an autumn evening, looking for the Big Dipper? It’s perhaps the most famous of all star patterns. You know you’re supposed to look northward. And you’re looking, but you can’t find it. Why not?

If you’re at a latitude of about 41 degrees north – or farther north – you will see the Dipper. From very northerly latitudes, the Big Dipper is circumpolar, or always above the northern horizon. If you’re below that latitude, though, you won’t find the Big Dipper in the evening now. In autumn, the Big Dipper is below your horizon during the evening hours.

Want to see it? If you’re in the southern U.S. or a comparable latitude, you’ll have to wait until the hours before dawn. At this time of the year, before dawn, you’ll easily see the Big Dipper ascending in the northeast.

To remember the best times to view the Big Dipper in the evening, remember the phrase: spring up and fall down. That’s because the Big Dipper shines way up high in the sky on spring evenings but close to the horizon on autumn evenings.

5 Dipper stars are related

So you might or might not be able to see the Big Dipper now. But you can think about it. Did you know that the distances of the stars in the Dipper reveal something interesting about them? Five of these seven stars have a physical relationship in space. That’s not always true of patterns on our sky’s dome. Most star patterns are made up of unrelated stars at vastly different distances.

Five of the Dipper’s stars – Merak, Mizar, Alioth, Megrez and Phecda – are part of a single star grouping. They probably were born together from a single cloud of gas and dust, and they’re still moving together as a family.

The other two stars in the Dipper – Dubhe and Alkaid – are unrelated to each other and to the other five. Here are the star distances to the Dipper’s stars:

Alkaid 101 light-years

Mizar 83 light-years

Alioth 81 light-years

Megrez 59 light-years

Phecda 83 light-years

Dubhe 123 light-years

Merak 80 light-years

What’s more, Dubhe and Alkaid are moving in an entirely different direction from the other five stars.

How the Big Dipper changes over time

And that’s why – millions of years from now – the Big Dipper will have lost its familiar dipper-like shape.

They do change, Here is a gif oh the big dipper changing over time pic.twitter.com/nwezuQnYyR

— LetsDoIt291 (@_lets_do_it_) June 24, 2018

Images of the Big Dipper

Bottom line: If you’re above 41 degrees north latitude, the Big Dipper star pattern is circumpolar; it stays in your sky always, circling around the northern pole star, Polaris. Below that latitude, the Dipper is below your horizon in the evening in autumn.

The post The Big Dipper: Why can’t you see it now? first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/AQI35Cm