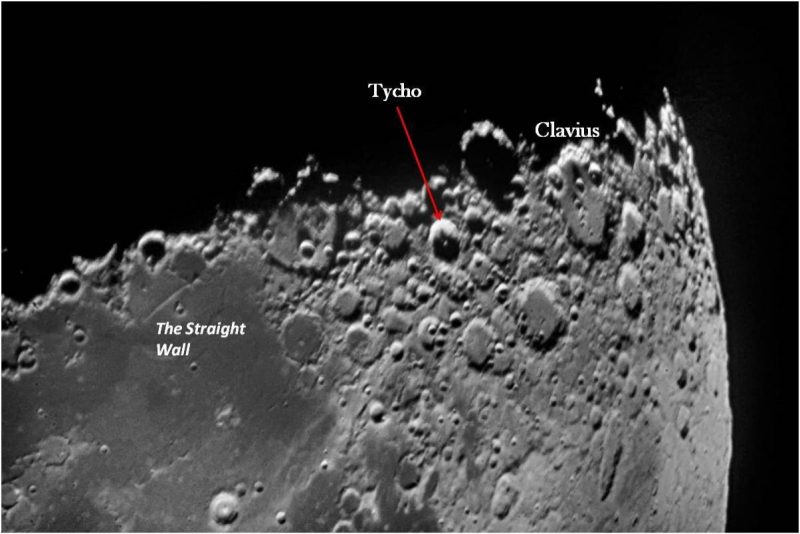

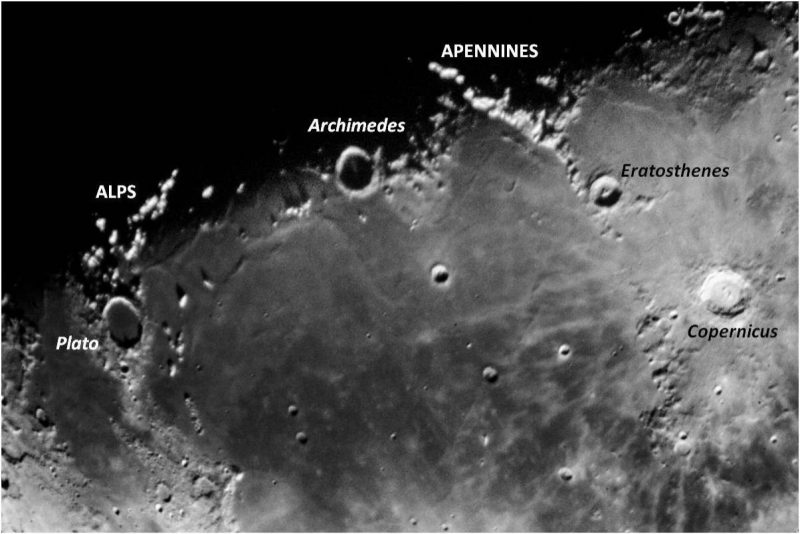

View at EarthSky Community Photos. | Eliot Herman captured this dramatic view of Mars this past weekend, when it was near the moon: “Moon and Mars clearing the ridgeline in Tucson, Arizona. The close conjunction of the moon and bright near-opposition Mars was a striking sight. The terminator of the moon shows the terrain picking up light on the craters and mountains leading to the observed discontinuities [the jagged appearance of the upper edge of the moon].” Thank you, Eliot! See more photos of last weekend’s moon and Mars.

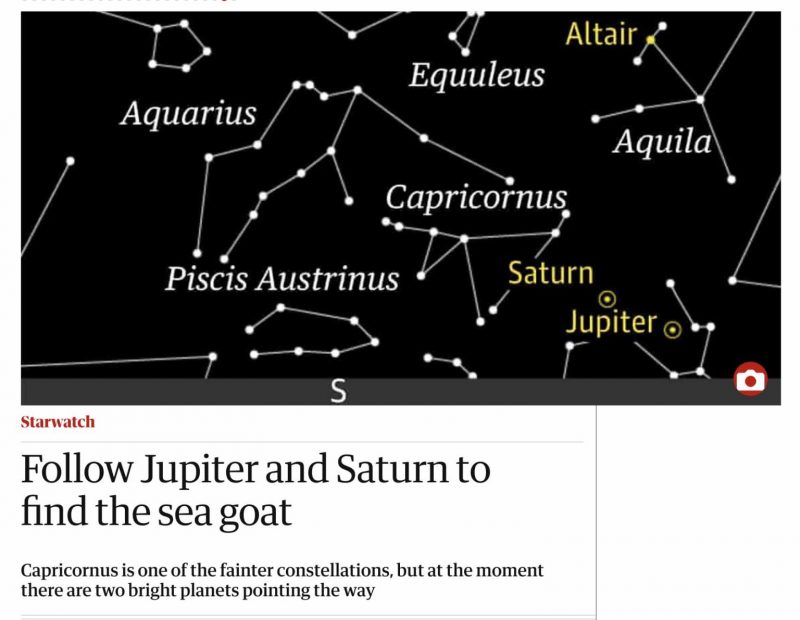

In the year 2018, Mars was brighter than all the stars. It was even brighter than the second-brightest planet, Jupiter. It was a blazing red dot of flame in our night sky for several months. In 2019, Mars was mostly faint. It was barely noticeable in our sky. And now Mars is bright again, brighter than all the stars. It’s not as bright as Jupiter yet, but it will be soon, for about a month surrounding mid-October 2020. Why? Why is Mars bright in some years, but faint in others? And why is Mars brightening so dramatically again now? Keep reading to learn why the appearance of Mars varies so widely in our sky, making Mars one of the most interesting planets to watch! Most importantly, learn how to start watching Mars now, so you can enjoy it for the remainder of this year.

September 2020 is a wonderful time to start watching Mars. It’s rising in the east now not long after the sun goes down. You can’t fail to recognize Mars. It’s very bright, and it’s very red in color. As the weeks go by, Mars will be rising earlier. By mid-October, it’ll be rising in the east as the sun sets in the west. After that, for the remainder of this year, Mars will be in our sky at sunset, fading in brightness as the year draws to a close, but still … a sight to see. To learn how to find Mars in the coming months, bookmark EarthSky’s planet guide.

More than any other bright planet, the appearance of Mars in our night sky changes from year to year. Its dramatic swings in brightness are part of the reason the early stargazers named Mars for their god of war; sometimes, the war god rests, and sometimes he grows fierce! Mars was bright in 2018 and faint again for most of 2019.

Now Mars is bright again.

Mars isn’t very big, so its brightness – when it is bright – isn’t due to its bigness, as is true of Jupiter. Mars’ brightness, or lack of brightness, is all about how close we are to the red planet. It’s all about where Earth and Mars are, relative to each other, in their respective orbits around the sun. Image via Lunar and Planetary Institute.

Why? Why does Mars sometimes appear very bright, and sometimes very faint?

The first thing to realize is that Mars isn’t a very big world. It’s only 4,219 miles (6,790 km) in diameter, making it only slightly more than half Earth’s size (7,922 miles or 12,750 km in diameter).

The small size of Mars is your first clue to its varying brightness. The small size means that, when Mars is bright, its brightness isn’t due to bigness, as is the case with the largest planet in our solar system, Jupiter.

Instead, the main reason for Mars’ extremes in brightness has to do with its nearness (or lack of nearness) to Earth.

Matt Pollack captured Mars from Little Tupper Lake in the Adirondacks of upstate New York in July 2018. Read more about this photo.

Mars orbits the sun one step outward from Earth. The distances between Earth and Mars change as both worlds orbit around the sun. Sometimes Earth and Mars are on the same side of the solar system, and hence near one another. At other times, as it was for much of 2017 and was again for much of 2019, Mars was moving on the opposite side of the solar system from Earth.

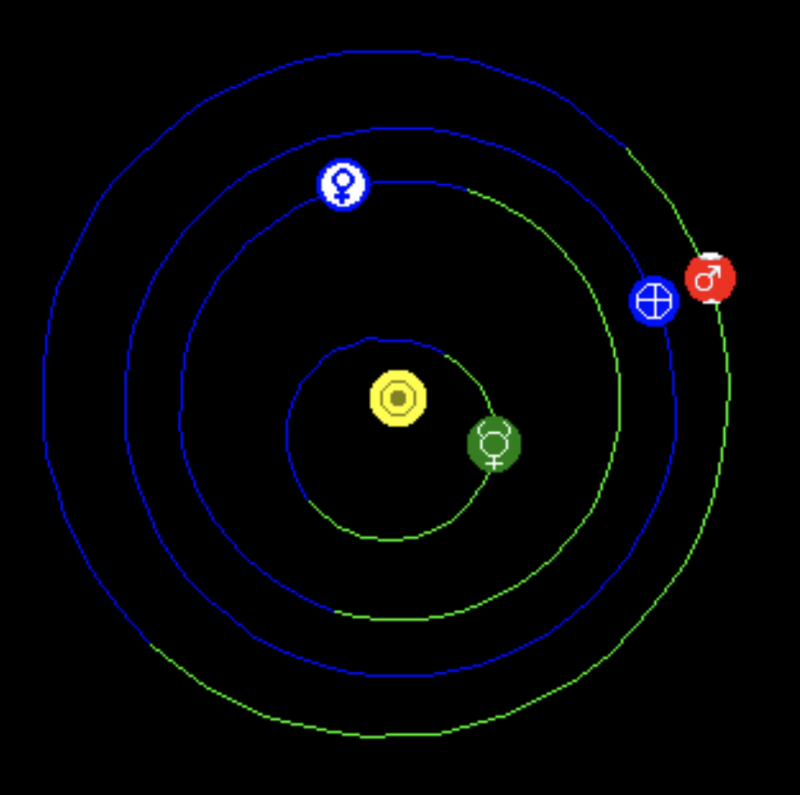

Look at the diagrams below, which show Earth and Mars in their respective orbits around the sun in mid-2018 and this month, June 2020 … and then in October 2020, when Earth and Mars will be closest for this two-year period.

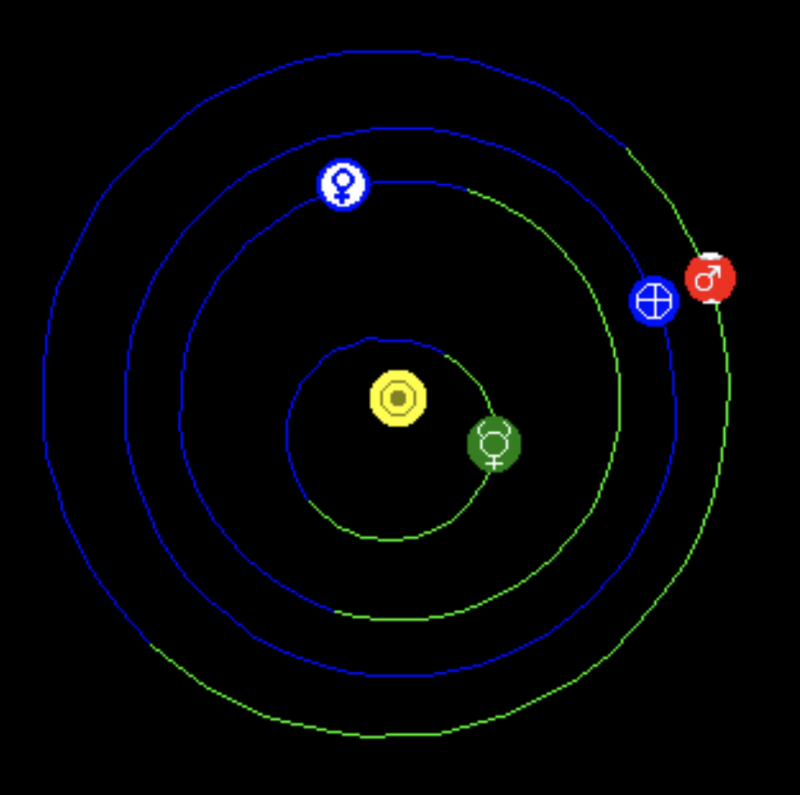

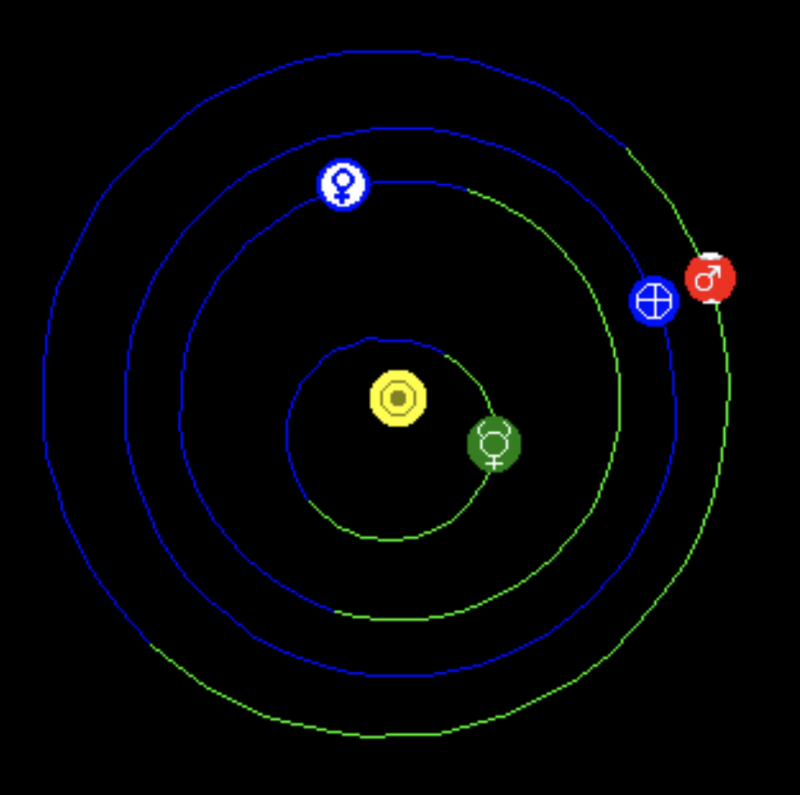

This chart shows the relative positions of Earth (blue) and Mars (red) at the time of Mars’ coming opposition on October 13, 2020. Around that time, Mars will appear bright in our sky again – and in the sky all night long – but it won’t be as bright as it was in 2018. Image via Fourmilab.

Earth takes a year to orbit the sun once. Mars takes about two years to orbit once. Opposition for Mars – when Earth passes between Mars and the sun – happens every two years and 50 days.

So Mars’ brightness waxes and wanes in our sky about every two years. Because of this, 2018 was a very, very special year for Mars, when the planet was brighter than it had been since 2003. Astronomers called it a perihelic opposition (or perihelic apparition) of Mars. In other words, in 2018, we went between Mars and the sun – bringing Mars to opposition in our sky – around the same time Mars came closest to the sun. The word perihelion refers to Mars’ closest point to the sun in orbit.

Maybe you can see that – in years when we pass between Mars and the sun, when Mars is also closest to the sun – Earth and Mars are closest. That’s what happened in 2018.

2003 was the previous perihelic opposition for Mars. The red planet came within 34.6 million miles (55.7 million km) of Earth, closer than at any time in over nearly 60,000 years! That was really something.

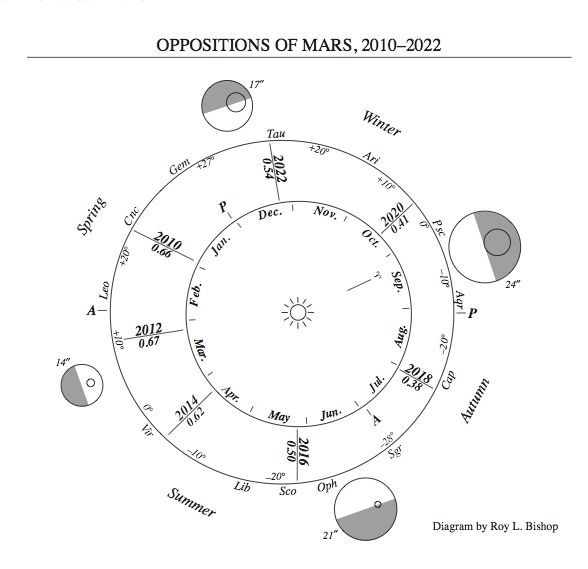

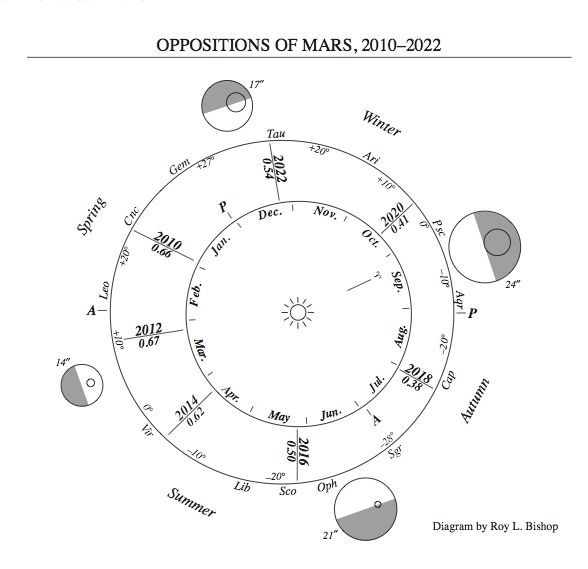

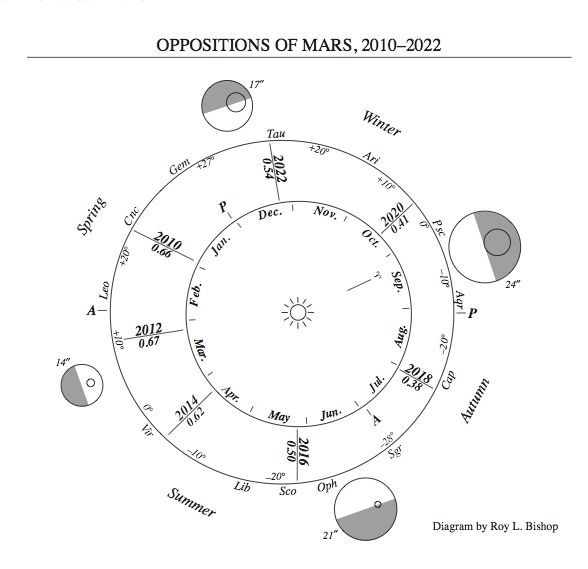

There’s a 15-year cycle of Mars, whereby the red planet is brighter and fainter at opposition. In July 2018, we were at the peak of the 2-year cycle – and the peak of the 15-year cycle – and Mars was very, very bright! In 2020, we’re at the peak of the 2-year cycle, and Earth and Mars are farther apart at Mars’ opposition than they were in 2018. Still, 2020’s opposition of Mars is excellent. Diagram by Roy L. Bishop. Copyright Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. Used with permission. Visit the RASC estore to purchase the Observer’s Handbook, a necessary tool for all skywatchers. Read more about this image.

And now? Earth will pass between Mars and the sun next on October 13, 2020. The red planet will appear brightest in our sky – very bright indeed and fiery red – around that time.

And thus Mars alternates years in being bright in our sky, or faint. 2019 was a dull year, but 2020 is an exciting one, for Mars!

Now is the time to start watching Mars. When you spot it, keep your eye on its, and enjoy its growing brightness. And think what’s causing the brightness change: our own Earth, rushing along in our smaller, faster orbit, trying to catch up.

Watch for Mars!

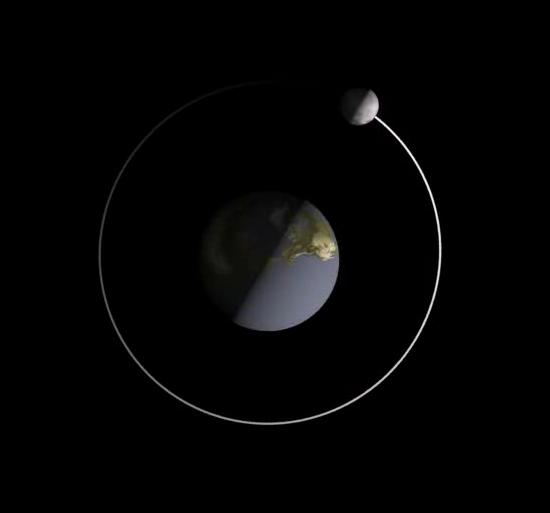

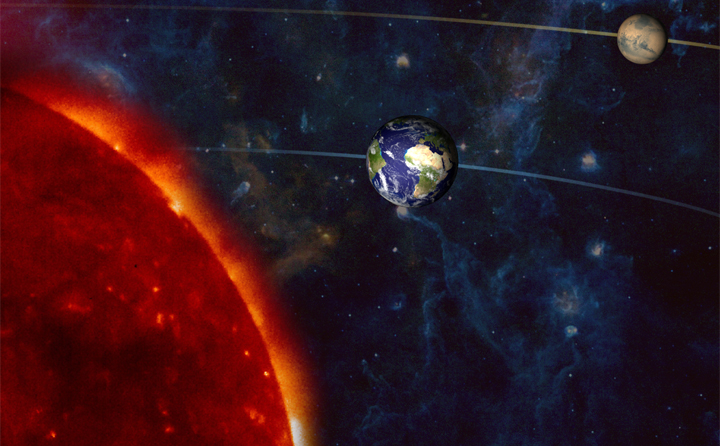

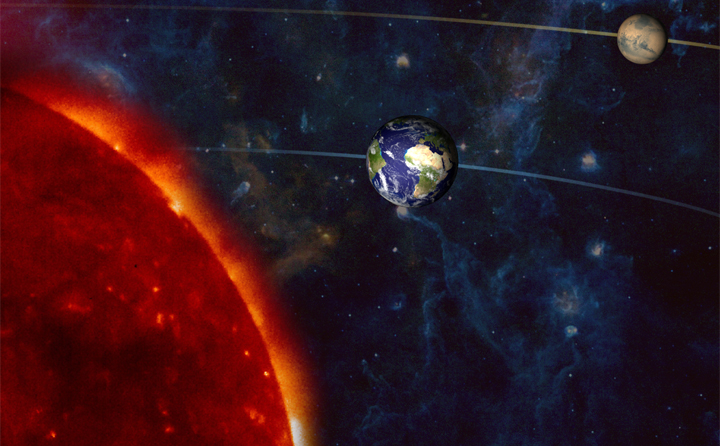

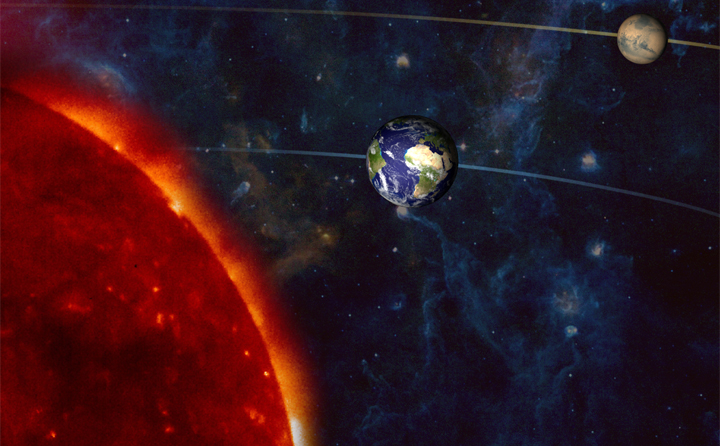

Artist’s concept of Earth (3rd planet from the sun) passing between the sun and Mars (4th planet from the sun). Not to scale. This is Mars’ opposition, when it appears opposite the sun in our sky. Image via NASA.

Bottom line: Mars alternates years in appearing bright and faint in our night sky. In 2018, our view of Mars was the best since 2003! In 2019, we were in one of Mars’ faint years. But 2020 has brought another bright year for Mars. If you start watching Mars in September 2020, you can see it at its best and enjoy it for the remaining months of this year.

Photos of bright Mars in 2018, from the EarthSky community

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2Puo0em

View at EarthSky Community Photos. | Eliot Herman captured this dramatic view of Mars this past weekend, when it was near the moon: “Moon and Mars clearing the ridgeline in Tucson, Arizona. The close conjunction of the moon and bright near-opposition Mars was a striking sight. The terminator of the moon shows the terrain picking up light on the craters and mountains leading to the observed discontinuities [the jagged appearance of the upper edge of the moon].” Thank you, Eliot! See more photos of last weekend’s moon and Mars.

In the year 2018, Mars was brighter than all the stars. It was even brighter than the second-brightest planet, Jupiter. It was a blazing red dot of flame in our night sky for several months. In 2019, Mars was mostly faint. It was barely noticeable in our sky. And now Mars is bright again, brighter than all the stars. It’s not as bright as Jupiter yet, but it will be soon, for about a month surrounding mid-October 2020. Why? Why is Mars bright in some years, but faint in others? And why is Mars brightening so dramatically again now? Keep reading to learn why the appearance of Mars varies so widely in our sky, making Mars one of the most interesting planets to watch! Most importantly, learn how to start watching Mars now, so you can enjoy it for the remainder of this year.

September 2020 is a wonderful time to start watching Mars. It’s rising in the east now not long after the sun goes down. You can’t fail to recognize Mars. It’s very bright, and it’s very red in color. As the weeks go by, Mars will be rising earlier. By mid-October, it’ll be rising in the east as the sun sets in the west. After that, for the remainder of this year, Mars will be in our sky at sunset, fading in brightness as the year draws to a close, but still … a sight to see. To learn how to find Mars in the coming months, bookmark EarthSky’s planet guide.

More than any other bright planet, the appearance of Mars in our night sky changes from year to year. Its dramatic swings in brightness are part of the reason the early stargazers named Mars for their god of war; sometimes, the war god rests, and sometimes he grows fierce! Mars was bright in 2018 and faint again for most of 2019.

Now Mars is bright again.

Mars isn’t very big, so its brightness – when it is bright – isn’t due to its bigness, as is true of Jupiter. Mars’ brightness, or lack of brightness, is all about how close we are to the red planet. It’s all about where Earth and Mars are, relative to each other, in their respective orbits around the sun. Image via Lunar and Planetary Institute.

Why? Why does Mars sometimes appear very bright, and sometimes very faint?

The first thing to realize is that Mars isn’t a very big world. It’s only 4,219 miles (6,790 km) in diameter, making it only slightly more than half Earth’s size (7,922 miles or 12,750 km in diameter).

The small size of Mars is your first clue to its varying brightness. The small size means that, when Mars is bright, its brightness isn’t due to bigness, as is the case with the largest planet in our solar system, Jupiter.

Instead, the main reason for Mars’ extremes in brightness has to do with its nearness (or lack of nearness) to Earth.

Matt Pollack captured Mars from Little Tupper Lake in the Adirondacks of upstate New York in July 2018. Read more about this photo.

Mars orbits the sun one step outward from Earth. The distances between Earth and Mars change as both worlds orbit around the sun. Sometimes Earth and Mars are on the same side of the solar system, and hence near one another. At other times, as it was for much of 2017 and was again for much of 2019, Mars was moving on the opposite side of the solar system from Earth.

Look at the diagrams below, which show Earth and Mars in their respective orbits around the sun in mid-2018 and this month, June 2020 … and then in October 2020, when Earth and Mars will be closest for this two-year period.

This chart shows the relative positions of Earth (blue) and Mars (red) at the time of Mars’ coming opposition on October 13, 2020. Around that time, Mars will appear bright in our sky again – and in the sky all night long – but it won’t be as bright as it was in 2018. Image via Fourmilab.

Earth takes a year to orbit the sun once. Mars takes about two years to orbit once. Opposition for Mars – when Earth passes between Mars and the sun – happens every two years and 50 days.

So Mars’ brightness waxes and wanes in our sky about every two years. Because of this, 2018 was a very, very special year for Mars, when the planet was brighter than it had been since 2003. Astronomers called it a perihelic opposition (or perihelic apparition) of Mars. In other words, in 2018, we went between Mars and the sun – bringing Mars to opposition in our sky – around the same time Mars came closest to the sun. The word perihelion refers to Mars’ closest point to the sun in orbit.

Maybe you can see that – in years when we pass between Mars and the sun, when Mars is also closest to the sun – Earth and Mars are closest. That’s what happened in 2018.

2003 was the previous perihelic opposition for Mars. The red planet came within 34.6 million miles (55.7 million km) of Earth, closer than at any time in over nearly 60,000 years! That was really something.

There’s a 15-year cycle of Mars, whereby the red planet is brighter and fainter at opposition. In July 2018, we were at the peak of the 2-year cycle – and the peak of the 15-year cycle – and Mars was very, very bright! In 2020, we’re at the peak of the 2-year cycle, and Earth and Mars are farther apart at Mars’ opposition than they were in 2018. Still, 2020’s opposition of Mars is excellent. Diagram by Roy L. Bishop. Copyright Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. Used with permission. Visit the RASC estore to purchase the Observer’s Handbook, a necessary tool for all skywatchers. Read more about this image.

And now? Earth will pass between Mars and the sun next on October 13, 2020. The red planet will appear brightest in our sky – very bright indeed and fiery red – around that time.

And thus Mars alternates years in being bright in our sky, or faint. 2019 was a dull year, but 2020 is an exciting one, for Mars!

Now is the time to start watching Mars. When you spot it, keep your eye on its, and enjoy its growing brightness. And think what’s causing the brightness change: our own Earth, rushing along in our smaller, faster orbit, trying to catch up.

Watch for Mars!

Artist’s concept of Earth (3rd planet from the sun) passing between the sun and Mars (4th planet from the sun). Not to scale. This is Mars’ opposition, when it appears opposite the sun in our sky. Image via NASA.

Bottom line: Mars alternates years in appearing bright and faint in our night sky. In 2018, our view of Mars was the best since 2003! In 2019, we were in one of Mars’ faint years. But 2020 has brought another bright year for Mars. If you start watching Mars in September 2020, you can see it at its best and enjoy it for the remaining months of this year.

Photos of bright Mars in 2018, from the EarthSky community

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2Puo0em