COVID-19 testing is essential in the UK’s fight against coronavirus and to help get cancer services back on track. We’ve estimated that between 21,000 and 37,000 COVID-19 tests must be done each day to ensure there are COVID-protected safe spaces for cancer diagnosis and treatment.

It’s vital for healthcare workers to know if their suspected symptoms are COVID-19, or if they’re carrying the virus despite not showing symptoms in order to protect themselves, their families and their patients. It’s also vital that patients are tested before they come into hospital to make sure it’s safe for them to have treatment.

In order to ramp up COVID-19 testing in the UK, a series of Lighthouse Labs have been assembled. Based in Cheshire, Glasgow, and Milton Keynes, they’re expected to be instrumental in the nation’s efforts to increase testing capacity.

Each of the sites took just three weeks to get up and running. But an empty lab is of no use, it must be filled with expert personnel.

We spoke to Cancer Research UK scientists who are volunteering at the Alderley Park Lighthouse lab in Cheshire and at the Beatson Institute in Glasgow, about how and why they decided to get involved in the initiative.

Isabelle Thompson, Alderley Park: “This pandemic is hopefully like nothing we’ll ever live through again and it’s pushing everyone to their limits”

Isabelle Thompson is a scientific officer at the Cancer Research UK Manchester Institute. Day-to-day, Thompson ensures the smooth running of the preclinical pharmacology laboratory at the Cancer Biomarker Centre, a growing team of 20 scientists who look at testing novel therapies for lung cancer.

Thompson told us how the Cancer Biomarker Centre receive regular updates on what’s going on in the Institute. And it was in one of these meetings that they were told about the opportunity to get involved in the Lighthouse Labs at Alderley Park.

“Because we’ve already got training in a lot of methods that can be used, they said that we would be able to volunteer our time in the labs,” says Thompson.

As soon as the plans were announced, Thompson knew she wanted to get involved, and signed up straight away. “I think if you can do something, then you really should. I felt that if I’ve got the skills to even just go in and do a bit of lab work, even if it’s just for a few months, then I then I think that is a worthwhile thing to do.”

The Alderley Park Lighthouse Lab has 5 different workstations, representing different stages of the testing procedure. Thompson describes how the samples go through a diligent process that begins with simply unpacking the swabs, to deactivating the virus and finding out whether the test is positive or negative.

“Each part of the process isn’t too complex,” Thompson explains, “it just needs to be very meticulously done, which I guess kind of suits the way a lot of scientist’s work”.

Thompson says the volunteers working there have experience of working in labs and are using lots of the same techniques and methods in the Lighthouse Lab that they use in their day jobs. And where their expertise lie depends at which workstation they’ll be placed.

With her background in molecular biology, Thompson went for one of the first workstations, where the live virus is isolated from patient samples and deactivated in preparation for the next step of the process, where some of the virus’ genetic material, known as RNA, is extracted.

But Thompson explains how there was still a lot to learn, and quickly. “It was new for me to be working with patient samples, and with a live virus.”

As well as adapting to new techniques, Thompson is adjusting to a whole new wardrobe. Volunteers must wear full PPE, including safety specs, a Howie-style lab coat, disposable sleeve, visors, extended cuffs and secondary gloves.

And it’s not just what to wear, it’s how to wear it. Anyone working in PPE must get training in how to operate efficiently whilst wearing the equipment. “There’s a lot of different PPE that you need to know how to use. So if your hands are in the hoods, working with the samples, you can’t bring them out, you can’t catch a sneeze. So it’s just a case of getting used to that.”

Recently, Thompson has been training new volunteers and working with a small team to implement new automated robotic systems, looking to optimise the number of samples they can process each day. The Alderley Park Lighthouse Lab is not short of things to do but morale remains high, “everyone’s coming together and everyone’s keen to help you learn”.

Dr Jo Birch, The Beatson Institute: “It’s nice to have that feeling of contributing to the cause”

Dr Jo Birch is a Cancer Research UK scientist who researches glioblastoma, an aggressive brain cancer at our Beatson Institute in Glasgow.

Since the pandemic began and laboratories across the country began to close, Birch was working from home, before being furloughed. “It is quite difficult to work from home, but I was doing as much as I could. I just had a review accepted, so I’d written that up, but it is limited when you can’t get back into the lab of course.”

Birch says it was difficult to leave the lab when they had to. “It’s very strange

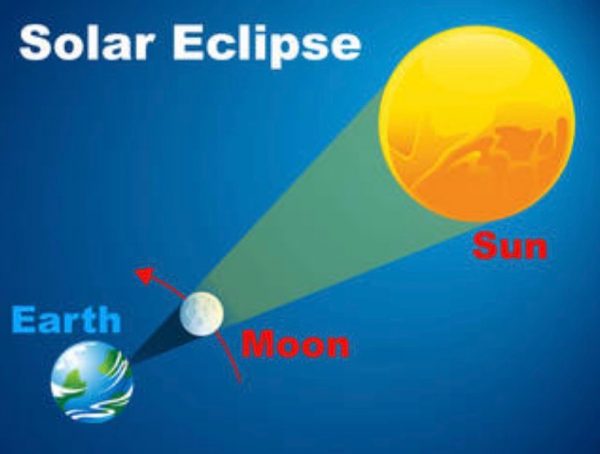

Jo in her full PPE.

because I think we’re all very passionate about what we do. It’s like a lifestyle, we all enjoy it and we’re very impassioned to make a difference with what we’re doing. So, it was a very strange feeling when we had to walk away.”

Birch received an e-mail from the University of Glasgow requesting volunteers to sign up for the Lighthouse Lab at the Beatson Institute. Like Thompson, Birch decided to sign up straight away. “You see so much on the news about current under-testing and how that really needs to be improved in order to get people moving and back to work, and everything getting back to normal – so it’s just good to be able to contribute to that.”

After receiving confirmation, Birch was back in the lab within two days, but this time helping the national effort to increasing COVID-19 testing.

Like Thompson, Birch has been assigned to a station at the beginning of the work chain, logging sample barcodes and assigning them to a 96-well plate.

She believes that the Institute has a good chance of getting through a significant number of samples and is ready to take on the challenge. “It’s fairly high-throughput, so it’s 90 samples that go into the machines at a time, along with six essential control samples to ensure the testing process is accurate. And they’ve got a bank of 18 machines now.”

Lilly

from Cancer Research UK – Science blog https://ift.tt/30o5jA9

COVID-19 testing is essential in the UK’s fight against coronavirus and to help get cancer services back on track. We’ve estimated that between 21,000 and 37,000 COVID-19 tests must be done each day to ensure there are COVID-protected safe spaces for cancer diagnosis and treatment.

It’s vital for healthcare workers to know if their suspected symptoms are COVID-19, or if they’re carrying the virus despite not showing symptoms in order to protect themselves, their families and their patients. It’s also vital that patients are tested before they come into hospital to make sure it’s safe for them to have treatment.

In order to ramp up COVID-19 testing in the UK, a series of Lighthouse Labs have been assembled. Based in Cheshire, Glasgow, and Milton Keynes, they’re expected to be instrumental in the nation’s efforts to increase testing capacity.

Each of the sites took just three weeks to get up and running. But an empty lab is of no use, it must be filled with expert personnel.

We spoke to Cancer Research UK scientists who are volunteering at the Alderley Park Lighthouse lab in Cheshire and at the Beatson Institute in Glasgow, about how and why they decided to get involved in the initiative.

Isabelle Thompson, Alderley Park: “This pandemic is hopefully like nothing we’ll ever live through again and it’s pushing everyone to their limits”

Isabelle Thompson is a scientific officer at the Cancer Research UK Manchester Institute. Day-to-day, Thompson ensures the smooth running of the preclinical pharmacology laboratory at the Cancer Biomarker Centre, a growing team of 20 scientists who look at testing novel therapies for lung cancer.

Thompson told us how the Cancer Biomarker Centre receive regular updates on what’s going on in the Institute. And it was in one of these meetings that they were told about the opportunity to get involved in the Lighthouse Labs at Alderley Park.

“Because we’ve already got training in a lot of methods that can be used, they said that we would be able to volunteer our time in the labs,” says Thompson.

As soon as the plans were announced, Thompson knew she wanted to get involved, and signed up straight away. “I think if you can do something, then you really should. I felt that if I’ve got the skills to even just go in and do a bit of lab work, even if it’s just for a few months, then I then I think that is a worthwhile thing to do.”

The Alderley Park Lighthouse Lab has 5 different workstations, representing different stages of the testing procedure. Thompson describes how the samples go through a diligent process that begins with simply unpacking the swabs, to deactivating the virus and finding out whether the test is positive or negative.

“Each part of the process isn’t too complex,” Thompson explains, “it just needs to be very meticulously done, which I guess kind of suits the way a lot of scientist’s work”.

Thompson says the volunteers working there have experience of working in labs and are using lots of the same techniques and methods in the Lighthouse Lab that they use in their day jobs. And where their expertise lie depends at which workstation they’ll be placed.

With her background in molecular biology, Thompson went for one of the first workstations, where the live virus is isolated from patient samples and deactivated in preparation for the next step of the process, where some of the virus’ genetic material, known as RNA, is extracted.

But Thompson explains how there was still a lot to learn, and quickly. “It was new for me to be working with patient samples, and with a live virus.”

As well as adapting to new techniques, Thompson is adjusting to a whole new wardrobe. Volunteers must wear full PPE, including safety specs, a Howie-style lab coat, disposable sleeve, visors, extended cuffs and secondary gloves.

And it’s not just what to wear, it’s how to wear it. Anyone working in PPE must get training in how to operate efficiently whilst wearing the equipment. “There’s a lot of different PPE that you need to know how to use. So if your hands are in the hoods, working with the samples, you can’t bring them out, you can’t catch a sneeze. So it’s just a case of getting used to that.”

Recently, Thompson has been training new volunteers and working with a small team to implement new automated robotic systems, looking to optimise the number of samples they can process each day. The Alderley Park Lighthouse Lab is not short of things to do but morale remains high, “everyone’s coming together and everyone’s keen to help you learn”.

Dr Jo Birch, The Beatson Institute: “It’s nice to have that feeling of contributing to the cause”

Dr Jo Birch is a Cancer Research UK scientist who researches glioblastoma, an aggressive brain cancer at our Beatson Institute in Glasgow.

Since the pandemic began and laboratories across the country began to close, Birch was working from home, before being furloughed. “It is quite difficult to work from home, but I was doing as much as I could. I just had a review accepted, so I’d written that up, but it is limited when you can’t get back into the lab of course.”

Birch says it was difficult to leave the lab when they had to. “It’s very strange

Jo in her full PPE.

because I think we’re all very passionate about what we do. It’s like a lifestyle, we all enjoy it and we’re very impassioned to make a difference with what we’re doing. So, it was a very strange feeling when we had to walk away.”

Birch received an e-mail from the University of Glasgow requesting volunteers to sign up for the Lighthouse Lab at the Beatson Institute. Like Thompson, Birch decided to sign up straight away. “You see so much on the news about current under-testing and how that really needs to be improved in order to get people moving and back to work, and everything getting back to normal – so it’s just good to be able to contribute to that.”

After receiving confirmation, Birch was back in the lab within two days, but this time helping the national effort to increasing COVID-19 testing.

Like Thompson, Birch has been assigned to a station at the beginning of the work chain, logging sample barcodes and assigning them to a 96-well plate.

She believes that the Institute has a good chance of getting through a significant number of samples and is ready to take on the challenge. “It’s fairly high-throughput, so it’s 90 samples that go into the machines at a time, along with six essential control samples to ensure the testing process is accurate. And they’ve got a bank of 18 machines now.”

Lilly

from Cancer Research UK – Science blog https://ift.tt/30o5jA9