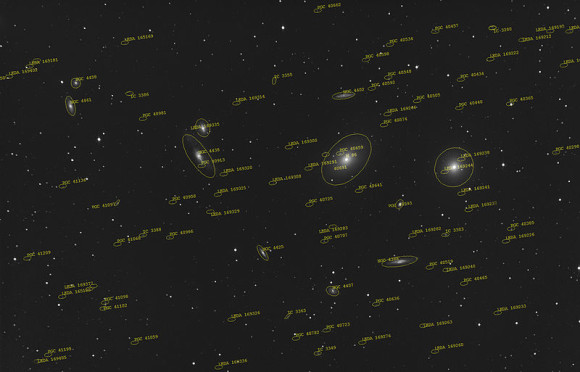

Mount Similaun glacier, where the border between Italy and Austria drifts with the ice. Image via Delfino Sisto Legnani/ Italian Limes.

This article – written by Elza Bouhassira – is republished with permission from GlacierHub.

Rifugio Guide del Cervino, a small mountain restaurant, opened in 1984 at a location high in the Italian Alps; now it might be in Switzerland. The restaurant has become the subject of a dispute between the two states due to a legal agreement which allows Italy’s northern border to move with the natural, morphological boundaries of glaciers’ frontiers, which largely follow the watersheds on either side of the ridges. The moving border has shifted over the last fifteen years since its creation as glaciers retreat and the restaurant may now be in Swiss territory. If decided to be in Switzerland, the restaurant would be subject to Swiss law, taxes, and potentially even customs; Swiss inspectors would need to approve every box of pasta and package of coffee brought up to the restaurant by cable car from Italy.

Rifugio Guide Del Cervino. Image via Franco56/ Wikimedia Commons.

Borders can follow artificial paths, like those on maps forming perfectly straight lines, independent of the physical and cultural landscapes they may be mincing. Others are fixed by natural boundaries like the Niagara River separating the US and Canada.

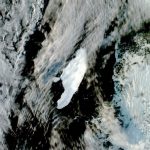

However, not all natural boundaries are as stable as they might appear. Italy, Austria, and Switzerland’s shared borders depend on the limits of the glaciers and they have been melting at increased rates due to climate change. This has caused the border to shift noticeably in recent years. The border lies primarily at high altitudes, among tall mountain peaks where it crosses white snowfields and icy blue glaciers.

Installation on the Similaun glacier. Image via Sisto Legnani/ Italian Limes.

The moving border is an unprecedented legal concept. It was established through an agreement between Italy and Austria in 2006 and another between Italy and Switzerland in 2009. France did not sign such an agreement because of post World War II territorial gains on the Italian side of the watershed it did not want to risk losing.

The moving border’s flexibility is a highly unusual case in a world where many borders serve to mark defined lines of inclusion and exclusion. International lawyer and Roma Tre University human rights professor Alice Riccardi told GlacierHub:

Borders today move following the policies of exclusion from/inclusion in pursued by States. For instance, when it comes to migration, EU South external borders happen to be already in Africa, where migrants are prevented from embarking towards Europe.

Since 2008, the Istituto Geografico Militare (IGM), which has defined and maintained Italy’s state borders since 1865, has conducted high-altitude survey expeditions every two years to search for shifts in the border and subsequently to update official maps. The collaborative team that conducts the survey is composed of an equal number of experts from IGM and representatives from cartographic institutes of neighboring states.

The concept of the moving border captured the attention of Marco Ferrari, an architect, and Dr. Elisa Pasqual, a visual designer. In 2014, they launched a research project and interactive installation called Italian Limes focused on the moving border. The word limes comes from Latin and was used by the Romans to describe a nebulous, unfixed fringe zone on the edge of their territorial control. The Romans viewed limes as ebbing and flowing as the Roman army advanced and retreated similar to how today the border moves as the ice drifts.

The project, featured in the 2014 Venice Biennale, explores the limits of natural borders when they are tested by long-term ecological processes and reveals how climate change has begun to wear on Western ideas of territory and borders. Ferrari told GlacierHub:

The project makes the speed of climate change visible because we are used to thinking of borders, glaciers, and mountains as things that stay fixed.

Climate change changes our conception of territory in a way that is not just material, it’s not just a disruption of infrastructure, but also of the geographical imagery of the planet itself. So the very idea of the border is put into crisis by climate change in this sense, it almost contradicts the possibility of being able to trace a border.

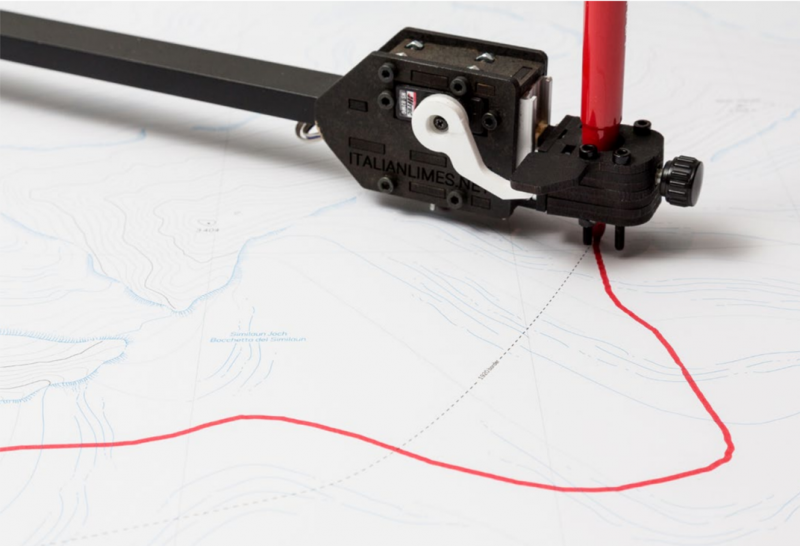

One of the high-precision GPS measurement tools used by the project at Grafferner Glacier. Image via Delfino Sisto Legnani/ Italian Limes.

The Italian Limes project takes measurements at the 1.5-kilometer (.9 mile) long Grafferner Glacier near Mount Similaun in the Ötztal Alps at the border of Italy and Austria. GPS measurement units were installed at the site to track changes to the glacier and watershed which broadcast their data to a machine, which prints a real-time representation of the moving border. Ferrari explained to GlacierHub:

By looking at the history of the border we came across this specific moment in time of the mobile border that was initially presented to us as an anecdote, as a funny curiosity, a weird glitch in the normal diplomatic management of the relationship between countries. Because of how it was presented to us, we almost didn’t focus on it, but on second thought we saw that this was the nexus that could allow us to talk about all the things we wanted to talk about; it could allow us to reveal the contradiction in this idea of a natural border–how even the mountains, even the watershed, even glaciers aren’t something that is forever, the fact that they are chosen to be borders is a clear political act and when these things move the contradiction gets exposed.

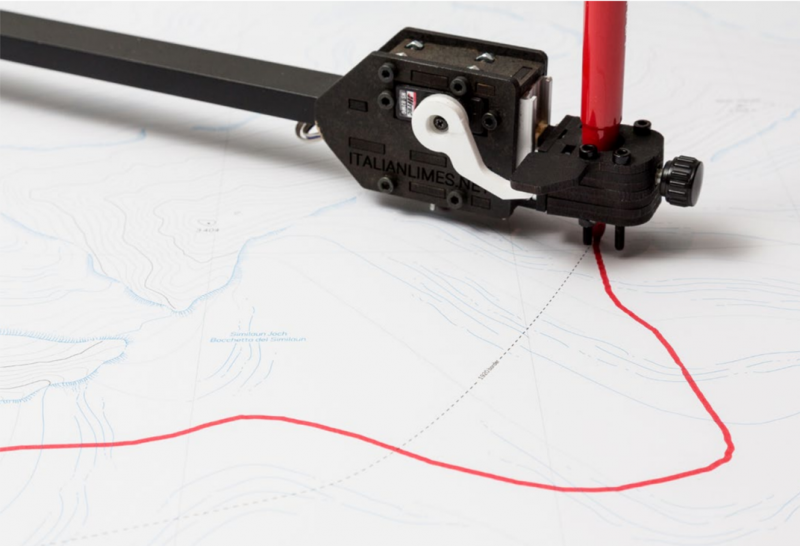

The installation showing a live representation of the border at ZKM, Karlsruhe. Image via Delfino Sisto Legnani/ Italian Limes.

The project grew to the point that Ferrari and Pasqual teamed up with architect and editor Andrea Bagnato to create A Moving Border: Alpine Cartographies of Climate Change, a 2019 book which builds on Italian Limes to map out the effects of climate change on geopolitical understandings of the border. Bagnato told GlacierHub:

I saw the project at the Venice Biennale 2014, it was a fantastic installation, and that’s when I proposed to Marco and Elisa to turn it into a book because I thought that after the work they had done physically going up on the glacier and producing these devices to visualize the movements of the glacier, there were a lot of issues to explore in more detail, historical and political issues. The book was a way to do that..

The book provides a kind of historical perspective of the border and also of climate change. Although we don’t address them directly in the book, I think it opens up to a lot of different geopolitical scenarios. Of course there are many situations in the world where borders pass on glaciers like in Chile/Argentina, India/Pakistan, and so on, where the geopolitics are far more heated than in Italy or Austria.

The Alps in the Trentino province of Italy. Image via Nawarona/ Flickr.

Ultimately, the effects of climate change will introduce stresses that borders cannot keep under control. The new, quick changes to the moving border are only one such instance. The U.S. state of Louisiana is rapidly losing ground to the waters on its coast. India and Bangladesh were involved in a dispute over who controlled an uninhabited sandbar that vanished beneath the rising seas. The province of Kashmir has long been a point of contention between Pakistan and India. If its glaciers melt and regional freshwater supply is put under great stress, conflict for control of the province could escalate significantly.

In an interview with Vice, Ferrari said:

Even the biggest and most stable things, like glaciers, mountains—these huge objects, they can change in a few years. We live on a planet that changes, and we try to make rules, to give meaning, but this meaning is completely artificial because nature, basically, doesn’t give a s**t.

Bottom line: Italy’s northern border with Switzerland is what’s known as a moving border, This is, it depends on the natural, morphological boundaries of glaciers’ frontiers. But in recent years, glaciers have been melting at increased rates due to climate change, causing much more dramatic – and controversial – border shifts.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/3dsNsvf

Mount Similaun glacier, where the border between Italy and Austria drifts with the ice. Image via Delfino Sisto Legnani/ Italian Limes.

This article – written by Elza Bouhassira – is republished with permission from GlacierHub.

Rifugio Guide del Cervino, a small mountain restaurant, opened in 1984 at a location high in the Italian Alps; now it might be in Switzerland. The restaurant has become the subject of a dispute between the two states due to a legal agreement which allows Italy’s northern border to move with the natural, morphological boundaries of glaciers’ frontiers, which largely follow the watersheds on either side of the ridges. The moving border has shifted over the last fifteen years since its creation as glaciers retreat and the restaurant may now be in Swiss territory. If decided to be in Switzerland, the restaurant would be subject to Swiss law, taxes, and potentially even customs; Swiss inspectors would need to approve every box of pasta and package of coffee brought up to the restaurant by cable car from Italy.

Rifugio Guide Del Cervino. Image via Franco56/ Wikimedia Commons.

Borders can follow artificial paths, like those on maps forming perfectly straight lines, independent of the physical and cultural landscapes they may be mincing. Others are fixed by natural boundaries like the Niagara River separating the US and Canada.

However, not all natural boundaries are as stable as they might appear. Italy, Austria, and Switzerland’s shared borders depend on the limits of the glaciers and they have been melting at increased rates due to climate change. This has caused the border to shift noticeably in recent years. The border lies primarily at high altitudes, among tall mountain peaks where it crosses white snowfields and icy blue glaciers.

Installation on the Similaun glacier. Image via Sisto Legnani/ Italian Limes.

The moving border is an unprecedented legal concept. It was established through an agreement between Italy and Austria in 2006 and another between Italy and Switzerland in 2009. France did not sign such an agreement because of post World War II territorial gains on the Italian side of the watershed it did not want to risk losing.

The moving border’s flexibility is a highly unusual case in a world where many borders serve to mark defined lines of inclusion and exclusion. International lawyer and Roma Tre University human rights professor Alice Riccardi told GlacierHub:

Borders today move following the policies of exclusion from/inclusion in pursued by States. For instance, when it comes to migration, EU South external borders happen to be already in Africa, where migrants are prevented from embarking towards Europe.

Since 2008, the Istituto Geografico Militare (IGM), which has defined and maintained Italy’s state borders since 1865, has conducted high-altitude survey expeditions every two years to search for shifts in the border and subsequently to update official maps. The collaborative team that conducts the survey is composed of an equal number of experts from IGM and representatives from cartographic institutes of neighboring states.

The concept of the moving border captured the attention of Marco Ferrari, an architect, and Dr. Elisa Pasqual, a visual designer. In 2014, they launched a research project and interactive installation called Italian Limes focused on the moving border. The word limes comes from Latin and was used by the Romans to describe a nebulous, unfixed fringe zone on the edge of their territorial control. The Romans viewed limes as ebbing and flowing as the Roman army advanced and retreated similar to how today the border moves as the ice drifts.

The project, featured in the 2014 Venice Biennale, explores the limits of natural borders when they are tested by long-term ecological processes and reveals how climate change has begun to wear on Western ideas of territory and borders. Ferrari told GlacierHub:

The project makes the speed of climate change visible because we are used to thinking of borders, glaciers, and mountains as things that stay fixed.

Climate change changes our conception of territory in a way that is not just material, it’s not just a disruption of infrastructure, but also of the geographical imagery of the planet itself. So the very idea of the border is put into crisis by climate change in this sense, it almost contradicts the possibility of being able to trace a border.

One of the high-precision GPS measurement tools used by the project at Grafferner Glacier. Image via Delfino Sisto Legnani/ Italian Limes.

The Italian Limes project takes measurements at the 1.5-kilometer (.9 mile) long Grafferner Glacier near Mount Similaun in the Ötztal Alps at the border of Italy and Austria. GPS measurement units were installed at the site to track changes to the glacier and watershed which broadcast their data to a machine, which prints a real-time representation of the moving border. Ferrari explained to GlacierHub:

By looking at the history of the border we came across this specific moment in time of the mobile border that was initially presented to us as an anecdote, as a funny curiosity, a weird glitch in the normal diplomatic management of the relationship between countries. Because of how it was presented to us, we almost didn’t focus on it, but on second thought we saw that this was the nexus that could allow us to talk about all the things we wanted to talk about; it could allow us to reveal the contradiction in this idea of a natural border–how even the mountains, even the watershed, even glaciers aren’t something that is forever, the fact that they are chosen to be borders is a clear political act and when these things move the contradiction gets exposed.

The installation showing a live representation of the border at ZKM, Karlsruhe. Image via Delfino Sisto Legnani/ Italian Limes.

The project grew to the point that Ferrari and Pasqual teamed up with architect and editor Andrea Bagnato to create A Moving Border: Alpine Cartographies of Climate Change, a 2019 book which builds on Italian Limes to map out the effects of climate change on geopolitical understandings of the border. Bagnato told GlacierHub:

I saw the project at the Venice Biennale 2014, it was a fantastic installation, and that’s when I proposed to Marco and Elisa to turn it into a book because I thought that after the work they had done physically going up on the glacier and producing these devices to visualize the movements of the glacier, there were a lot of issues to explore in more detail, historical and political issues. The book was a way to do that..

The book provides a kind of historical perspective of the border and also of climate change. Although we don’t address them directly in the book, I think it opens up to a lot of different geopolitical scenarios. Of course there are many situations in the world where borders pass on glaciers like in Chile/Argentina, India/Pakistan, and so on, where the geopolitics are far more heated than in Italy or Austria.

The Alps in the Trentino province of Italy. Image via Nawarona/ Flickr.

Ultimately, the effects of climate change will introduce stresses that borders cannot keep under control. The new, quick changes to the moving border are only one such instance. The U.S. state of Louisiana is rapidly losing ground to the waters on its coast. India and Bangladesh were involved in a dispute over who controlled an uninhabited sandbar that vanished beneath the rising seas. The province of Kashmir has long been a point of contention between Pakistan and India. If its glaciers melt and regional freshwater supply is put under great stress, conflict for control of the province could escalate significantly.

In an interview with Vice, Ferrari said:

Even the biggest and most stable things, like glaciers, mountains—these huge objects, they can change in a few years. We live on a planet that changes, and we try to make rules, to give meaning, but this meaning is completely artificial because nature, basically, doesn’t give a s**t.

Bottom line: Italy’s northern border with Switzerland is what’s known as a moving border, This is, it depends on the natural, morphological boundaries of glaciers’ frontiers. But in recent years, glaciers have been melting at increased rates due to climate change, causing much more dramatic – and controversial – border shifts.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/3dsNsvf