COVID-19 is delaying cancer research and treatment. We catch up with some of the cancer researchers who are using their expertise, experience and equipment to help tackle COVID-19 and get cancer services back on track.

The shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE) for NHS workers has been a headline issue in the UK.

Standard PPE kit includes an apron, gloves, a surgical mask and eye protection, which is vital to the safety of those working at the front line of the coronavirus crisis and they people they’re looking after. Without it, they’re at a higher risk of catching COVID-19.

Alongside widespread COVID-19 testing, PPE is essential to protect healthcare workers and ensure cancer care can continue during the pandemic.

It’s in exceptional times like these that people across the country have been motivated to respond, doing everything from sewing scrubs and facemasks at home to donate to the NHS to volunteering to deliver medicines or food to people at risk.

We spoke to two of our scientists who are doing their bit to help COVID-19 efforts – using their expertise in 3D printing to help provide essential PPE to health workers around the country.

Steve Bagley, Manchester: ‘I wondered how I could help’

The 3D printer at the Manchester Institute is being used by Steve Bagley to produce essential PPE.

Steve Bagley is a cancer scientist from our Manchester Institute. He normally works with microscopes and X-ray machinery to analyse cancer cells, but became increasingly aware of the lack of PPE for our frontline staff. “I saw that there was a need for more protective equipment for those working in the NHS, so I wondered how I could help.”

Bagley has produced over 200 head straps.

While the Institute’s labs at Alderley Park have been temporarily closed for research, Bagley has been tasked with the job of looking after and maintaining the specialist lab equipment, including a 3D printer.

“I’m very familiar with the 3D printer, as it’s a piece of kit we use regularly to create parts for microscopes and other lab equipment,” says Bagley. “And it occurred to me that I could use this to create plastic headbands for protective face masks.”

Once Bagley had worked out a template, with correct dimensions for the headbands, he began a mini production line, printing the plastic headbands in the lab.

So far, Bagley has produced over 200 protective face masks for frontline healthcare staff. The PPE will be distributed to hospitals across the North West, including The Christie NHS Foundation Trust in Manchester.

“I really wanted to do something to support all those who are working so hard on the frontline in the battle against Covid-19. And the sooner we beat this virus, the sooner we can return to beating cancer.”

Marcel Gehrung, Cambridge:

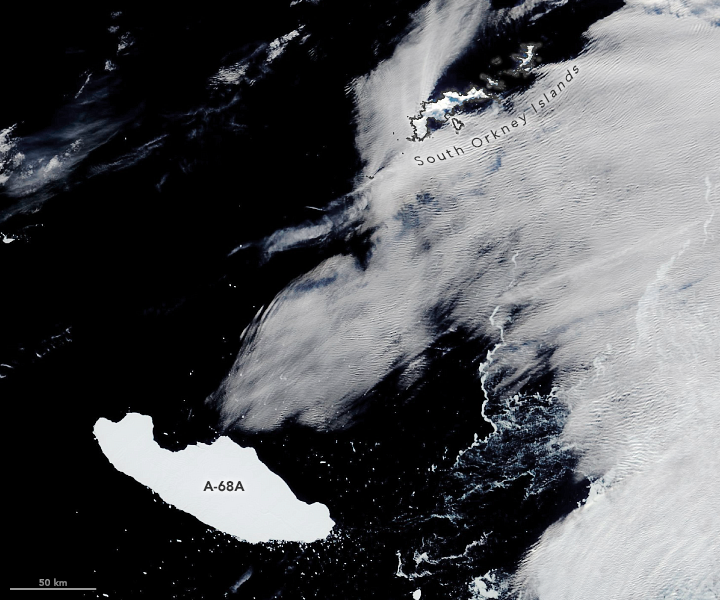

Some of the protective visors manufactured by Marcel Gehrung.

“There is this very public discussion about the lack of personal protective equipment for different health care professionals in the NHS,” says Marcel Gehrung, a PhD student at the Cancer Research UK Cambridge Institute, investigating machine learning applications in healthcare, with a focus on medical imaging. Whilst completing his PhD in Cambridge, Gehrung co-founded Cyted, a new diagnostics company that uses artificial intelligence to detect cancers earlier.

And it was this work that drew him into the discussions around PPE.

The company has been involved with the commercialisation of the Cytosponge – a ‘sponge-on-a-string’ test that can detect oesophageal cancer earlier. Cytosponge was developed to help pick up Barrett’s oesophagus, a condition that can develop into oesophageal cancer, but plans were adapted in the face of the COVID-19 outbreak.

“We were contacted by a lot of trusts saying they don’t have endoscopy capacity anymore, and their waiting lists for people who are being referred for endoscopy are getting very long,” Gehrung explains. To help mitigate this reduction in endoscopies the Cytosponge – the test used to diagnose oesophageal conditions, such as Barrett’s oesophagus and cancer – has been piloted in Addenbrooke’s hospital as an emergency response.

His involvement in rolling out the Cytosponge test has given him a real insight into the needs of healthcare workers.

Gehrung and his team were asked about sourcing protective equipment by the nurses running the Cytosponge testing facility at Addenbrooke’s hospital in Cambridge. The Cytosponge test requires nurses to retrieve the device from the patient’s stomach, which sometimes involves coughing as it passes the throat, “so it is very important for the healthcare staff to have face shields”.

After a couple of days of thinking about where they could source face masks, Gehrung took matters into his own hands. “I started talking to our Institute Director and Director of Operations and said that we could actually use the Institute’s printers to make more visors.”

Gehrung transported the equipment, which wasn’t being used at the time, from the Institute to his home in Cambridge, and is now producing visors using multiple 3D printers in his living room.

“So far we just have produced them on demand,” says Gehrung, “we had this domino reaction happening where people would say ‘oh yeah I need another two and I have a few colleagues who are trying to source them as well’”.

Although it’s hard to say exactly, Gehrung estimates he’s made between 150–250 protective visors.

Gehrung notes the importance of thinking beyond the area you’re working in to find solutions to tricky situations. “If someone talks about academia and science, they tell you it’s about vertical depth, and having maximum understanding of a topic, but breadth is very helpful for this situation, as it helps you think outside of the box.”

Lilly

from Cancer Research UK – Science blog https://ift.tt/2YDDh2K

COVID-19 is delaying cancer research and treatment. We catch up with some of the cancer researchers who are using their expertise, experience and equipment to help tackle COVID-19 and get cancer services back on track.

The shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE) for NHS workers has been a headline issue in the UK.

Standard PPE kit includes an apron, gloves, a surgical mask and eye protection, which is vital to the safety of those working at the front line of the coronavirus crisis and they people they’re looking after. Without it, they’re at a higher risk of catching COVID-19.

Alongside widespread COVID-19 testing, PPE is essential to protect healthcare workers and ensure cancer care can continue during the pandemic.

It’s in exceptional times like these that people across the country have been motivated to respond, doing everything from sewing scrubs and facemasks at home to donate to the NHS to volunteering to deliver medicines or food to people at risk.

We spoke to two of our scientists who are doing their bit to help COVID-19 efforts – using their expertise in 3D printing to help provide essential PPE to health workers around the country.

Steve Bagley, Manchester: ‘I wondered how I could help’

The 3D printer at the Manchester Institute is being used by Steve Bagley to produce essential PPE.

Steve Bagley is a cancer scientist from our Manchester Institute. He normally works with microscopes and X-ray machinery to analyse cancer cells, but became increasingly aware of the lack of PPE for our frontline staff. “I saw that there was a need for more protective equipment for those working in the NHS, so I wondered how I could help.”

Bagley has produced over 200 head straps.

While the Institute’s labs at Alderley Park have been temporarily closed for research, Bagley has been tasked with the job of looking after and maintaining the specialist lab equipment, including a 3D printer.

“I’m very familiar with the 3D printer, as it’s a piece of kit we use regularly to create parts for microscopes and other lab equipment,” says Bagley. “And it occurred to me that I could use this to create plastic headbands for protective face masks.”

Once Bagley had worked out a template, with correct dimensions for the headbands, he began a mini production line, printing the plastic headbands in the lab.

So far, Bagley has produced over 200 protective face masks for frontline healthcare staff. The PPE will be distributed to hospitals across the North West, including The Christie NHS Foundation Trust in Manchester.

“I really wanted to do something to support all those who are working so hard on the frontline in the battle against Covid-19. And the sooner we beat this virus, the sooner we can return to beating cancer.”

Marcel Gehrung, Cambridge:

Some of the protective visors manufactured by Marcel Gehrung.

“There is this very public discussion about the lack of personal protective equipment for different health care professionals in the NHS,” says Marcel Gehrung, a PhD student at the Cancer Research UK Cambridge Institute, investigating machine learning applications in healthcare, with a focus on medical imaging. Whilst completing his PhD in Cambridge, Gehrung co-founded Cyted, a new diagnostics company that uses artificial intelligence to detect cancers earlier.

And it was this work that drew him into the discussions around PPE.

The company has been involved with the commercialisation of the Cytosponge – a ‘sponge-on-a-string’ test that can detect oesophageal cancer earlier. Cytosponge was developed to help pick up Barrett’s oesophagus, a condition that can develop into oesophageal cancer, but plans were adapted in the face of the COVID-19 outbreak.

“We were contacted by a lot of trusts saying they don’t have endoscopy capacity anymore, and their waiting lists for people who are being referred for endoscopy are getting very long,” Gehrung explains. To help mitigate this reduction in endoscopies the Cytosponge – the test used to diagnose oesophageal conditions, such as Barrett’s oesophagus and cancer – has been piloted in Addenbrooke’s hospital as an emergency response.

His involvement in rolling out the Cytosponge test has given him a real insight into the needs of healthcare workers.

Gehrung and his team were asked about sourcing protective equipment by the nurses running the Cytosponge testing facility at Addenbrooke’s hospital in Cambridge. The Cytosponge test requires nurses to retrieve the device from the patient’s stomach, which sometimes involves coughing as it passes the throat, “so it is very important for the healthcare staff to have face shields”.

After a couple of days of thinking about where they could source face masks, Gehrung took matters into his own hands. “I started talking to our Institute Director and Director of Operations and said that we could actually use the Institute’s printers to make more visors.”

Gehrung transported the equipment, which wasn’t being used at the time, from the Institute to his home in Cambridge, and is now producing visors using multiple 3D printers in his living room.

“So far we just have produced them on demand,” says Gehrung, “we had this domino reaction happening where people would say ‘oh yeah I need another two and I have a few colleagues who are trying to source them as well’”.

Although it’s hard to say exactly, Gehrung estimates he’s made between 150–250 protective visors.

Gehrung notes the importance of thinking beyond the area you’re working in to find solutions to tricky situations. “If someone talks about academia and science, they tell you it’s about vertical depth, and having maximum understanding of a topic, but breadth is very helpful for this situation, as it helps you think outside of the box.”

Lilly

from Cancer Research UK – Science blog https://ift.tt/2YDDh2K