The Geminid meteor shower peaks overnight on December 13-14. It’s a great year for the Geminids! Join EarthSky’s Deborah Byrd for details.

EarthSky’s 2026 lunar calendar is available now. Get yours today! Makes a great gift.

The Geminid meteor shower peaks all night on December 13-14, 2025. The planet Jupiter – brightest starlike object in the sky from late evening until dawn – will be near the Geminid radiant point. The waning crescent moon won’t interfere with these meteors this year. Many Geminid meteors are bright! Will any of them be as bright as Jupiter? Observe from a rural location from late evening until dawn. Have fun!

Predicted peak in 2025: is predicted** for 3 UTC on December 14 (9 p.m. CST on December 13).

When to watch: Since the radiant rises in mid- to late evening, you can watch for Geminids nearly all night – from late evening until dawn – on December 13-14. The nights before and after might be good as well.

Overall duration of shower: November 19 to December 24. This time period is when we’re passing through the Geminid meteor stream in space!

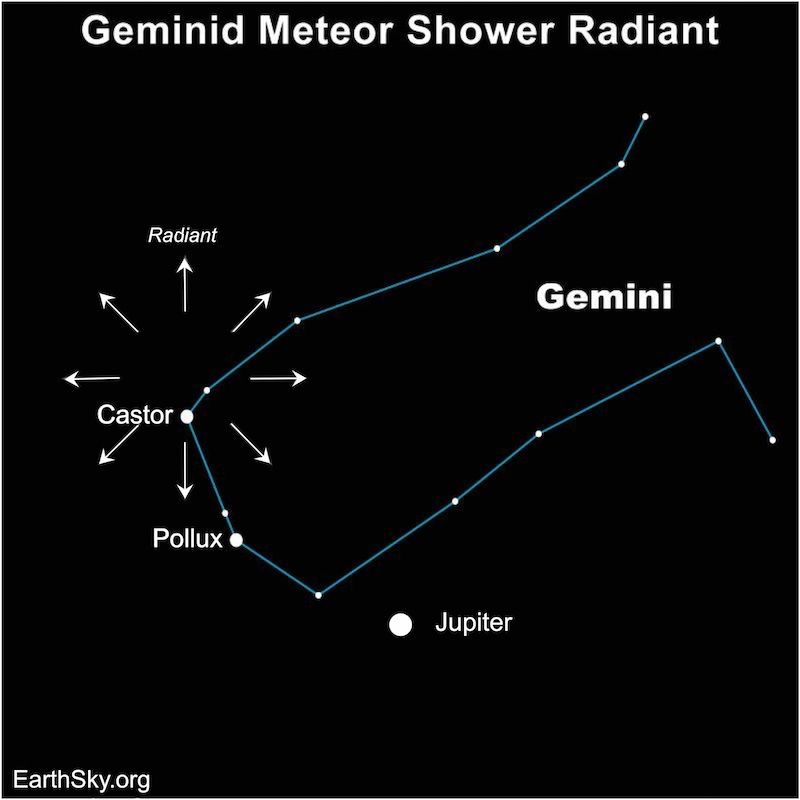

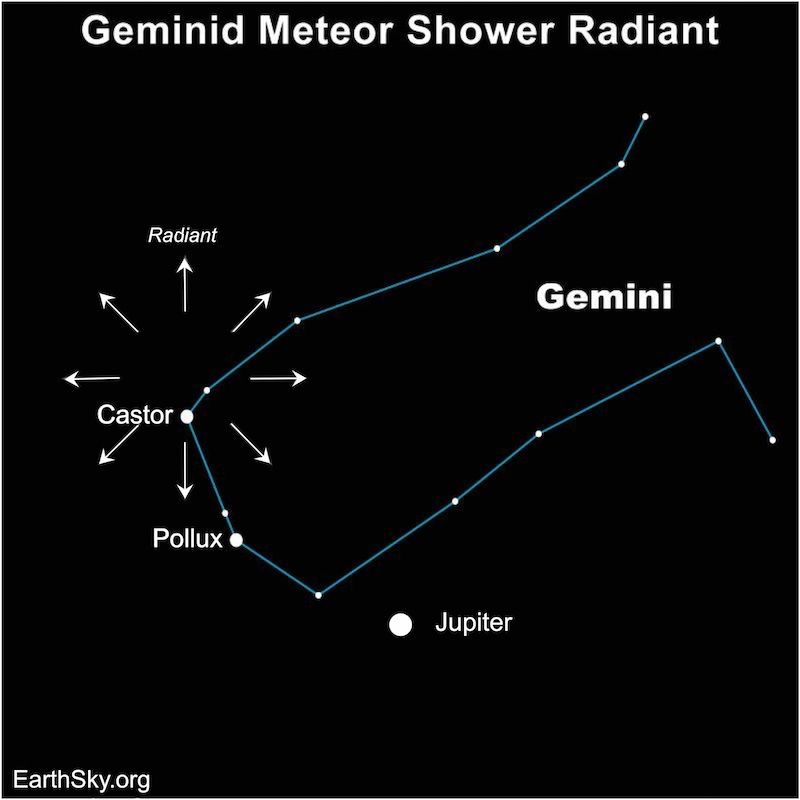

Radiant: Rises in mid- to late evening, highest around 2 a.m. Note that, in 2025, the bright planet Jupiter is near the shower’s radiant point. See charts below.

Nearest moon phase: In 2025, the last quarter moon falls at 20:52 UTC on December 11. So a waning crescent moon will rise a few hours after midnight on December 14. It’ll enhance – rather than interfere – with Geminid meteor watching this year.

Expected meteors at peak, under ideal conditions: Under a dark sky with no moon, you might catch 120 Geminid meteors per hour!

Note: The bold, bright – and sometimes colorful – Geminids give us one of the Northern Hemisphere’s best showers, especially in years when there’s no moon. They’re visible, at lower rates, from the Southern Hemisphere, too. The meteors are plentiful, rivaling the August Perseids, and the Geminid shower is one of the most beloved meteor showers of the year.

The Geminid meteor shower radiant point

The Geminids’ radiant point nearly coincides with the bright star Castor in Gemini. That’s a chance alignment, of course, as Castor lies some 52 light-years away. Meanwhile, these meteors burn up in our world’s upper atmosphere, approximately 60 miles (100 km) above Earth’s surface.

Castor is noticeably near another bright star, the golden star Pollux of Gemini. And what’s that bright “star” on the other side of Pollux in 2025? It’s the planet Jupiter, the brightest starlike object in the December night sky.

Jupiter will let you easily picture the Geminids’ radiant point in 2025. But you don’t need to find a meteor shower’s radiant point to see the meteors. Meteors in annual showers appear in all parts of the sky. It’s even possible to have your back to the constellation Gemini and see a Geminid meteor fly by.

If you trace the path of a Geminid meteor backwards, though, you’ll find it comes from the radiant point.

Report a fireball (very bright meteor) to the American Meteor Society: It’s fun and easy!

Parent comet of the Geminid meteor shower

From the late, great Don Machholz (1952-2022), who discovered 12 comets …

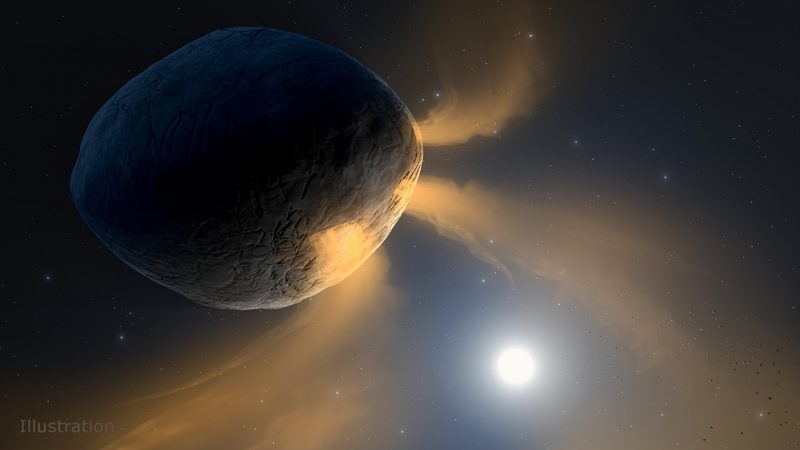

An asteroid known as 3200 Phaethon is responsible for the Geminid meteor shower. This origin differs from most meteor showers, which result from comets, not asteroids. What’s the difference between a comet and an asteroid?

A comet is a dirty snowball, with a solid nucleus covered by a layer of ice which sublimates (turns from a solid to a gas) as the comet nears the sun. Comets are typically lightweight, with a density slightly heavier than water. They revolve around the sun in elongated orbits, going close to the sun, then going far from the sun. Seen through a telescope, a comet will show a coma, or head of the comet, as a nebulous patch of light around the nucleus, when it gets close to the sun. But when seen far from the sun, most comets appear starlike, because you see only the nucleus.

An asteroid, on the other hand, is a rock. Typically, an asteroid’s orbit is more circular than that of a comet. Through a telescope an asteroid also appears starlike.

These definitions worked well until a few decades ago. Larger telescopes began discovering asteroids far from the sun, and some of these objects, as they approached the sun, grew comas and tails, requiring the change of designation from asteroid to comet. For example, an odd object named Chiron, considered an asteroid when discovered in 1977, was reclassified as a comet in 1989 when it showed a coma. It orbits the sun every 50 years and travels from just inside the orbit of Saturn to the orbit of Uranus.

So an object initially considered an asteroid can be reclassified as a comet. Then, can the opposite occur? Can a comet be reclassified as an asteroid? Yes, it can. It is possible that a comet can shut down when its volatile materials become trapped beneath the nucleus’ surface. This is known as a dormant comet. When the comet loses all of its volatile materials, it is known as an extinct comet. The asteroid 3200 Phaethon seems to be an example of either a dormant or an extinct comet.

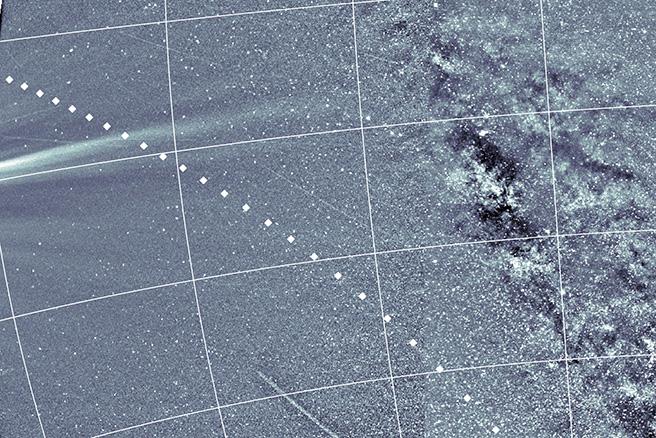

3200 Phaethon discovered in 1983

3200 Phaethon was discovered on images taken by IRAS (Infrared Astronomical Satellite) on October 11, 1983, by Simon Green and John Davies. Initially named 1983 TB, it was given an asteroid name, 3200 Phaethon, in 1985. After the orbit was calculated, Fred Whipple announced that this asteroid has the same orbit as the Geminid meteor shower. This was very unusual, since an asteroid had never been associated with a meteor shower. It’s still not known how material from the asteroid’s surface, or interior, is released into the meteoroid stream.

3200 Phaethon gets very close to the sun, half of the distance of the innermost planet, Mercury. Then it ventures out past the orbit of Mars. So the meteor material intersects Earth’s orbit every mid-December. Hence, the Geminid meteor shower.

The Japanese spacecraft DESTINY+ (Demonstration and Experiment of Space Technology for Interplanetary Voyage with Phaethon Flyby and Dust Science) is expected to launch in 2028 to visit this asteroid. It should arrive in the year 2030. One proposal from 2006 suggested crashing an object into 3200 Phaethon to produce an artificial meteor shower to better study the asteroid. DESTINY+, however, will not be hitting the asteroid.

Meanwhile, every year around mid-December, Earth will be passing through the stream of particles in space left behind by this asteroid. Those asteroid bits will hit our atmosphere and vaporize, and you can see them this December, and every December.

Read more about asteroid Phaethon

Geminid meteors tend to be bright

The Geminid meteor shower – always a favorite among the annual meteor showers – is expected to peak in 2025 on December 13-14. The Geminids are a reliable shower, especially for those who watch around 2 a.m. (your local time) from a dark-sky location.

We also often hear from those who see Geminid meteors in the late evening hours. Late evening is the best time to see super-bright earthgrazers. Read more about them below.

Geminid meteors tend to be bright and are often colorful. And in 2025, the bright planet Jupiter is in the sky all night, near the shower’s radiant point. Are any of the Geminids you see brighter than Jupiter?

How many meteors, when to look

The zenithal hourly rate for this shower is 120. During an optimum night for the Geminids, it’s possible to see 120 meteors – or more – per hour. Will you see that many? Maybe. On a dark night, near the peak of the shower (for all time zones), you can surely catch at least 50 or more meteors per hour.

Watch for earthgrazers in the evening hours

If the 2 a.m. observing time isn’t practical for you, don’t give up! Sure, you won’t see as many Geminid meteors in the early evening, when the constellation Gemini sits close to the eastern horizon, but since the radiant rises mid-evening it’s worth a try. Plus, the evening hours are the best time to try and catch an earthgrazer.

An earthgrazer is a slooow-moving, looong-lasting meteor that travels horizontally across the sky. Earthgrazers are rare but prove to be especially memorable, if you should be lucky enough to catch one.

6 tips for Geminid meteor watchers

- The most important thing, if you’re serious about watching meteors, is a dark, open sky.

- The peak time of night for Geminids is around 2 a.m. for all parts of the globe. In 2025, a waning crescent moon will not interfere with the Geminid meteor shower.

- When you’re meteor-watching, it’s good to bring along a buddy. Then the two of you can watch in different directions. When someone sees one, call out, “Meteor!” This technique will let you see more meteors than one person watching alone will see.

- Be sure to give yourself at least an hour (or more) of observing time. It takes about 20 minutes for your eyes to adapt to the dark.

- Be aware that meteors often come in spurts, interspersed with lulls.

- Special equipment? None needed. Definitely consider a sleeping bag to stay warm. A thermos with a warm drink and a snack are always welcome. Plan to sprawl back in a hammock, lawn chair, pile of hay or blanket on the ground. Lie back in comfort, and look upward. The meteors will appear in all parts of the sky. Put your electronics away; they’ll ruin your night vision.

Geminid meteor shower photos from the EarthSky Community

Bottom line: The 2025 Geminid meteor shower peaks in a dark sky overnight on December 13-14. It’s one of the best meteor showers of the year and you can watch for them all night. Under ideal conditions, you might see over 100 meteors per hour.

**Predicted peak times and dates for meteor showers are from the American Meteor Society. Note that meteor shower peak times can vary.

Meteor showers: Tips for watching the show

Learn how to shoot photos of meteors

When can YOU see the 1st-ever human-made meteor shower?

The post Geminid meteor shower peaks in dark skies December 13-14 first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/lFO2ETw

The Geminid meteor shower peaks overnight on December 13-14. It’s a great year for the Geminids! Join EarthSky’s Deborah Byrd for details.

EarthSky’s 2026 lunar calendar is available now. Get yours today! Makes a great gift.

The Geminid meteor shower peaks all night on December 13-14, 2025. The planet Jupiter – brightest starlike object in the sky from late evening until dawn – will be near the Geminid radiant point. The waning crescent moon won’t interfere with these meteors this year. Many Geminid meteors are bright! Will any of them be as bright as Jupiter? Observe from a rural location from late evening until dawn. Have fun!

Predicted peak in 2025: is predicted** for 3 UTC on December 14 (9 p.m. CST on December 13).

When to watch: Since the radiant rises in mid- to late evening, you can watch for Geminids nearly all night – from late evening until dawn – on December 13-14. The nights before and after might be good as well.

Overall duration of shower: November 19 to December 24. This time period is when we’re passing through the Geminid meteor stream in space!

Radiant: Rises in mid- to late evening, highest around 2 a.m. Note that, in 2025, the bright planet Jupiter is near the shower’s radiant point. See charts below.

Nearest moon phase: In 2025, the last quarter moon falls at 20:52 UTC on December 11. So a waning crescent moon will rise a few hours after midnight on December 14. It’ll enhance – rather than interfere – with Geminid meteor watching this year.

Expected meteors at peak, under ideal conditions: Under a dark sky with no moon, you might catch 120 Geminid meteors per hour!

Note: The bold, bright – and sometimes colorful – Geminids give us one of the Northern Hemisphere’s best showers, especially in years when there’s no moon. They’re visible, at lower rates, from the Southern Hemisphere, too. The meteors are plentiful, rivaling the August Perseids, and the Geminid shower is one of the most beloved meteor showers of the year.

The Geminid meteor shower radiant point

The Geminids’ radiant point nearly coincides with the bright star Castor in Gemini. That’s a chance alignment, of course, as Castor lies some 52 light-years away. Meanwhile, these meteors burn up in our world’s upper atmosphere, approximately 60 miles (100 km) above Earth’s surface.

Castor is noticeably near another bright star, the golden star Pollux of Gemini. And what’s that bright “star” on the other side of Pollux in 2025? It’s the planet Jupiter, the brightest starlike object in the December night sky.

Jupiter will let you easily picture the Geminids’ radiant point in 2025. But you don’t need to find a meteor shower’s radiant point to see the meteors. Meteors in annual showers appear in all parts of the sky. It’s even possible to have your back to the constellation Gemini and see a Geminid meteor fly by.

If you trace the path of a Geminid meteor backwards, though, you’ll find it comes from the radiant point.

Report a fireball (very bright meteor) to the American Meteor Society: It’s fun and easy!

Parent comet of the Geminid meteor shower

From the late, great Don Machholz (1952-2022), who discovered 12 comets …

An asteroid known as 3200 Phaethon is responsible for the Geminid meteor shower. This origin differs from most meteor showers, which result from comets, not asteroids. What’s the difference between a comet and an asteroid?

A comet is a dirty snowball, with a solid nucleus covered by a layer of ice which sublimates (turns from a solid to a gas) as the comet nears the sun. Comets are typically lightweight, with a density slightly heavier than water. They revolve around the sun in elongated orbits, going close to the sun, then going far from the sun. Seen through a telescope, a comet will show a coma, or head of the comet, as a nebulous patch of light around the nucleus, when it gets close to the sun. But when seen far from the sun, most comets appear starlike, because you see only the nucleus.

An asteroid, on the other hand, is a rock. Typically, an asteroid’s orbit is more circular than that of a comet. Through a telescope an asteroid also appears starlike.

These definitions worked well until a few decades ago. Larger telescopes began discovering asteroids far from the sun, and some of these objects, as they approached the sun, grew comas and tails, requiring the change of designation from asteroid to comet. For example, an odd object named Chiron, considered an asteroid when discovered in 1977, was reclassified as a comet in 1989 when it showed a coma. It orbits the sun every 50 years and travels from just inside the orbit of Saturn to the orbit of Uranus.

So an object initially considered an asteroid can be reclassified as a comet. Then, can the opposite occur? Can a comet be reclassified as an asteroid? Yes, it can. It is possible that a comet can shut down when its volatile materials become trapped beneath the nucleus’ surface. This is known as a dormant comet. When the comet loses all of its volatile materials, it is known as an extinct comet. The asteroid 3200 Phaethon seems to be an example of either a dormant or an extinct comet.

3200 Phaethon discovered in 1983

3200 Phaethon was discovered on images taken by IRAS (Infrared Astronomical Satellite) on October 11, 1983, by Simon Green and John Davies. Initially named 1983 TB, it was given an asteroid name, 3200 Phaethon, in 1985. After the orbit was calculated, Fred Whipple announced that this asteroid has the same orbit as the Geminid meteor shower. This was very unusual, since an asteroid had never been associated with a meteor shower. It’s still not known how material from the asteroid’s surface, or interior, is released into the meteoroid stream.

3200 Phaethon gets very close to the sun, half of the distance of the innermost planet, Mercury. Then it ventures out past the orbit of Mars. So the meteor material intersects Earth’s orbit every mid-December. Hence, the Geminid meteor shower.

The Japanese spacecraft DESTINY+ (Demonstration and Experiment of Space Technology for Interplanetary Voyage with Phaethon Flyby and Dust Science) is expected to launch in 2028 to visit this asteroid. It should arrive in the year 2030. One proposal from 2006 suggested crashing an object into 3200 Phaethon to produce an artificial meteor shower to better study the asteroid. DESTINY+, however, will not be hitting the asteroid.

Meanwhile, every year around mid-December, Earth will be passing through the stream of particles in space left behind by this asteroid. Those asteroid bits will hit our atmosphere and vaporize, and you can see them this December, and every December.

Read more about asteroid Phaethon

Geminid meteors tend to be bright

The Geminid meteor shower – always a favorite among the annual meteor showers – is expected to peak in 2025 on December 13-14. The Geminids are a reliable shower, especially for those who watch around 2 a.m. (your local time) from a dark-sky location.

We also often hear from those who see Geminid meteors in the late evening hours. Late evening is the best time to see super-bright earthgrazers. Read more about them below.

Geminid meteors tend to be bright and are often colorful. And in 2025, the bright planet Jupiter is in the sky all night, near the shower’s radiant point. Are any of the Geminids you see brighter than Jupiter?

How many meteors, when to look

The zenithal hourly rate for this shower is 120. During an optimum night for the Geminids, it’s possible to see 120 meteors – or more – per hour. Will you see that many? Maybe. On a dark night, near the peak of the shower (for all time zones), you can surely catch at least 50 or more meteors per hour.

Watch for earthgrazers in the evening hours

If the 2 a.m. observing time isn’t practical for you, don’t give up! Sure, you won’t see as many Geminid meteors in the early evening, when the constellation Gemini sits close to the eastern horizon, but since the radiant rises mid-evening it’s worth a try. Plus, the evening hours are the best time to try and catch an earthgrazer.

An earthgrazer is a slooow-moving, looong-lasting meteor that travels horizontally across the sky. Earthgrazers are rare but prove to be especially memorable, if you should be lucky enough to catch one.

6 tips for Geminid meteor watchers

- The most important thing, if you’re serious about watching meteors, is a dark, open sky.

- The peak time of night for Geminids is around 2 a.m. for all parts of the globe. In 2025, a waning crescent moon will not interfere with the Geminid meteor shower.

- When you’re meteor-watching, it’s good to bring along a buddy. Then the two of you can watch in different directions. When someone sees one, call out, “Meteor!” This technique will let you see more meteors than one person watching alone will see.

- Be sure to give yourself at least an hour (or more) of observing time. It takes about 20 minutes for your eyes to adapt to the dark.

- Be aware that meteors often come in spurts, interspersed with lulls.

- Special equipment? None needed. Definitely consider a sleeping bag to stay warm. A thermos with a warm drink and a snack are always welcome. Plan to sprawl back in a hammock, lawn chair, pile of hay or blanket on the ground. Lie back in comfort, and look upward. The meteors will appear in all parts of the sky. Put your electronics away; they’ll ruin your night vision.

Geminid meteor shower photos from the EarthSky Community

Bottom line: The 2025 Geminid meteor shower peaks in a dark sky overnight on December 13-14. It’s one of the best meteor showers of the year and you can watch for them all night. Under ideal conditions, you might see over 100 meteors per hour.

**Predicted peak times and dates for meteor showers are from the American Meteor Society. Note that meteor shower peak times can vary.

Meteor showers: Tips for watching the show

Learn how to shoot photos of meteors

When can YOU see the 1st-ever human-made meteor shower?

The post Geminid meteor shower peaks in dark skies December 13-14 first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/lFO2ETw