Mira the Wonderful

Although stars appear to shine at a constant brilliance, many are variable stars. They brighten and dim over many different timescales. Their changes in brightness are often too small to be perceptible to the unaided eye. But the star Mira, aka Omicron Ceti, is different. Its brightness changes are large and distinctly noticeable to the eye.

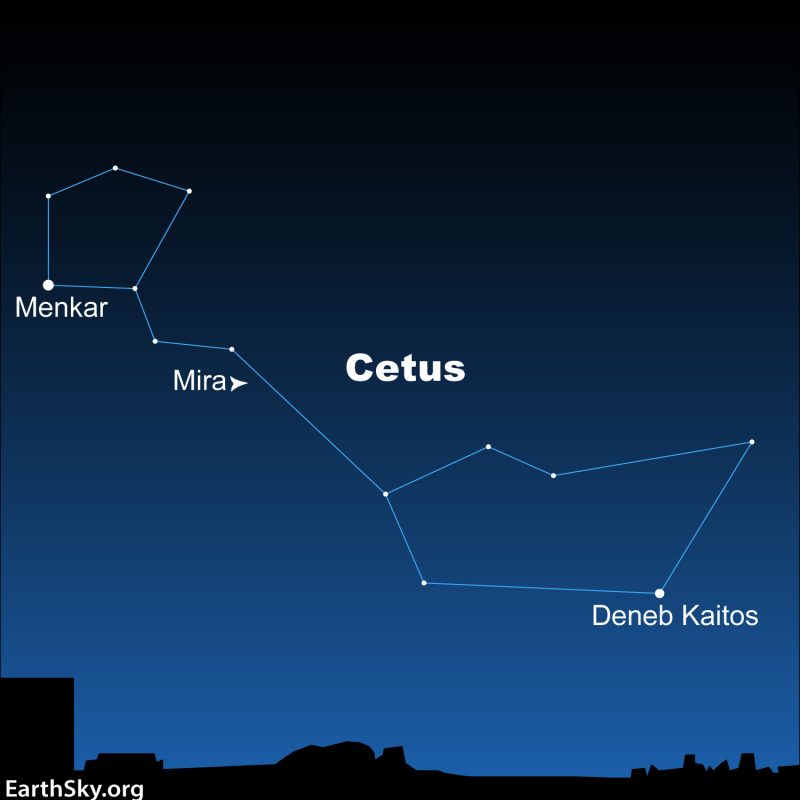

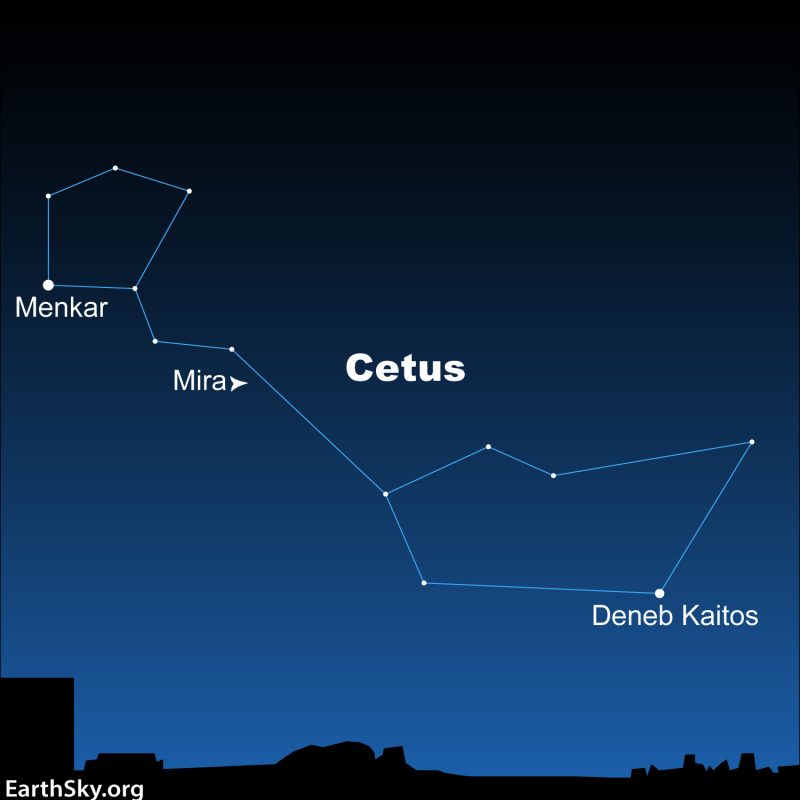

Depending on when you look for Mira, this reddish star in the constellation Cetus the Whale might or might not be visible. It goes through its bright-to-faint-to-bright cycle about every 332 days. And Mira is not visible from late March to June because it’s too close to the sun then.

If you’d like to see this unusual star in 2026, now’s your chance.

Mira brightened enough in December 2025 to be visible to the eye in a dark sky. It should reach its maximum brightness in February or March 2026, when it’ll be setting late evening (your local time). Note, it’ll set four minutes earlier each day. Generally, you can see it with the unaided eye for about six weeks before it reaches maximum brightness and over two months afterwards. Of course that depends on when Mira reaches its maximum brightness. In 2026, Mira might still be visible to the eye in a dark sky when it’s lost in the sun’s glare.

Then in 2027, it’s maximum will be in January sometime.

How it got its nickname

Early astronomers noticed this star’s dramatic and regular changes in brightness. Mira sparkles in the sky, getting progressively dimmer, and a few months later, it’s gone! Then, after some months, it’s back again. Its brightness changes led the 17th century astronomer Johannes Hevelius to name the star Mira, from the Latin word for wonderful or astonishing.

So now Mira is on track to hit another brightness peak in February or March 2026. How bright will it get? That’s a question many variable star observers are eagerly waiting to find out. You can check current observations here.

Now you see it, now you don’t

Mira has an average peak brightness of magnitude 3.5. It’s not one of the sky’s brightest stars, even when brightest. It gradually fades to around magnitude 9 (too faint to see with the eye; for reference, in a dark sky, the unaided eye can barely detect a magnitude 6 star). Then it rebounds back to its peak brightness. So Mira undergoes about a 159-fold change in brightness, as it moves through its 332-day brightness cycle.

It’s impossible to predict exactly how bright or faint Mira will become at each maximum. Have a look at the graph below, called a light curve. Mira-watchers contribute their observations to the American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO). The AAVSO creates an ongoing light curve for Mira, using its Light Curve Generator tool. The light curve below covers the last 10 years. The parts of the plot with no data were when Mira was close to the sun. In 2019 and 2022, Mira was as bright as magnitude 2. That’s almost as bright as Polaris, the North Star, not the sky’s brightest star, but a respectably bright star.

How to see Mira

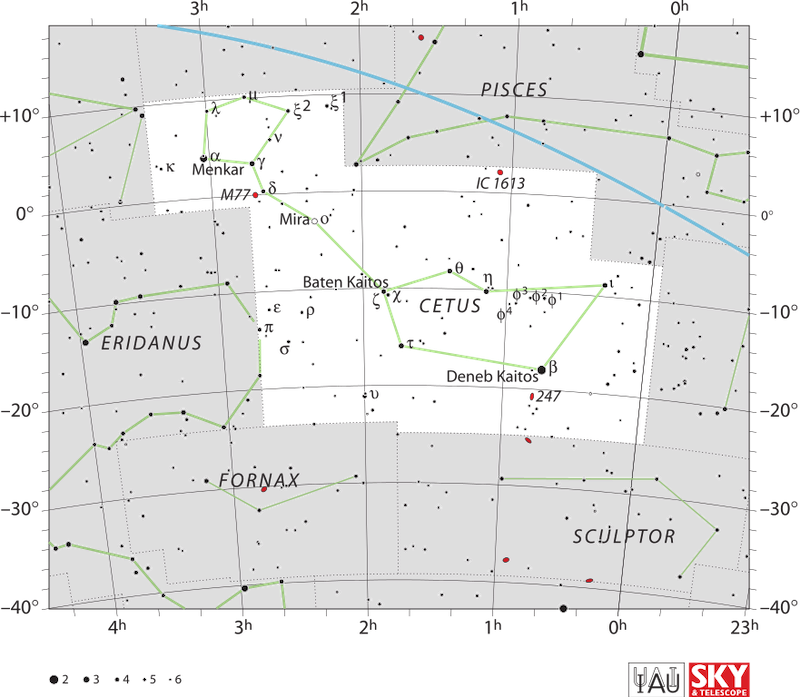

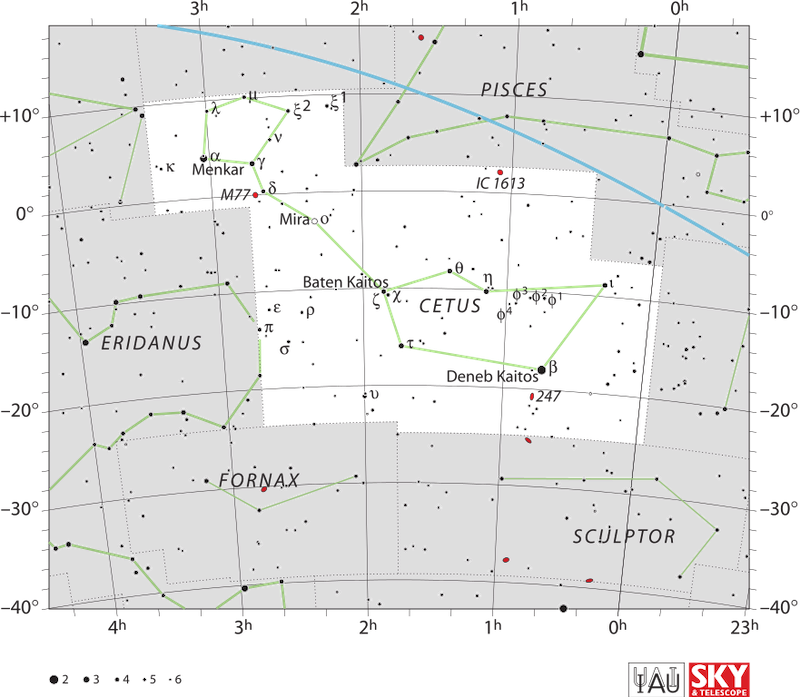

Catch Mira while now while it’s heading toward its brightest! Then keep watching it as it fades away. Its peak brightness for 2026 comes in February or March. At that time, Mira is in the southwest as darkness falls (your local time) and sets a few hours before midnight. However, it’s in the constellation of Cetus which isn’t a prominent constellation. It’s faint. You’ll want a dark sky to see it. If you have a dark sky, you can pick out the Whale’s lopsided pentagon of a Head. Check Stellarium for a precise view and timing from your location.

Look for it again in early 2027

The next upcoming predicted maximum brightnesses for Mira is January or February 2027. Look for Mira around then! That’s when, according to predictions, it should be at its brightest.

Also, look at the chart below. Notice that the distinctive nearby V-shaped Hyades star cluster in Taurus the Bull points to Cetus and its star Mira.

Mira science

Early astronomers marveled at Mira’s brightness changes and considered them a great mystery. But modern astronomers know Mira as a red giant star. It’s slightly more massive than our sun but at least 330 times larger in size. Its huge surface area makes it more than 8,000 times more luminous. Mira is some 300 light-years away. It’s thought to be around 6 billion years old. Mira has a faint white dwarf companion star.

There are many types of pulsating variable stars known today. But Mira was the first of its type discovered. And so, astronomers named an entire class of variable stars after it. Mira variables are stars that have one to a few times the mass of our sun. They’re near the end of their stellar lifetime, at the red giant stage. Mira variables have pulsation periods from 80 to 1,000 days, brightness variations from 2.5 to 10 visual magnitudes, and tend to shed material from their outer layers.

So Mira’s brightness changes aren’t due, for example, to some external factor (such as a disk around the star). They’re caused by the actual expansion and contraction of the entire star, every 332 days. This expansion-contraction oscillation is a complex phenomenon related to changes in the rate that radiation escapes from the star.

Mira’s story is of special interest since our sun will someday follow the same stellar evolutionary path. About 5 billion years from now, our sun will become a Mira variable.

Why Mira’s brightness changes

For much of its existence, Mira converted hydrogen to helium at its core as a main sequence star. When that fuel was exhausted, its core contracted, causing it to heat up. That heating triggered a new round of hydrogen-to-helium nuclear fusion in a shell around the core, causing Mira to balloon in size into a red giant star. Meanwhile, the collapsing core continued to heat up until it became hot enough for the fusion of helium to carbon, and some oxygen.

Mira is currently at a stage in its stellar evolution called the asymptotic giant branch. Its core of carbon and oxygen is inert. However, the star is still actively “burning” a layer of helium around the core, converting it to carbon. And just outside it, a shell of hydrogen is being converted to helium.

The outer layers of Mira are weakly held by gravity and are starting to waft away. Mira will eventually shed its material to form a planetary nebula, with its exposed hot core – a white dwarf star – left behind.

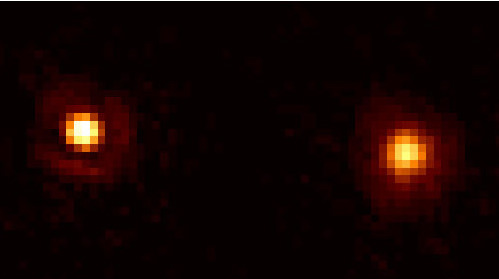

Mira’s 13-light-year-long tail

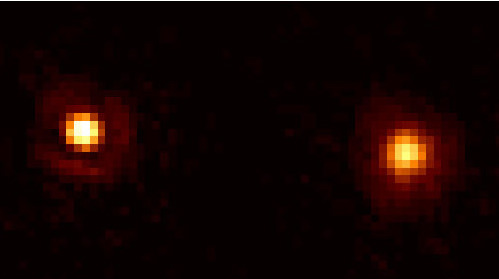

In 2006, the Galaxy Evolution Explorer telescope obtained ultraviolet images of Mira that surprised scientists. They revealed a long comet-like tail of material trailing the star as it sped through ambient galactic gas. Mira moves through space at about 290,000 miles per hour (466,700 km/h). The tail, about 13 light-years long, is composed of gases and dust released by Mira over the last 30,000 years. The amount of gases and dust in Mira’s tail equal about 3,000 times the Earth’s mass.

Mira in history

Did the earliest stargazers notice Mira as it appeared disappeared and reappeared? If they did, they left no records of this star. The star’s earliest known history begins only 400 years ago, when Dutch astronomer David Fabricius first noticed Mira. That was in the year 1596. He assumed Mira was a nova because, as novae do, the star faded away after a few months. However, Fabricus relocated the star 13 years later. It must have surprised him!

Another Dutch astronomer, Johannes Holwarda, was the first to identify Mira as a variable star, and determined a period of 11 months. That value was refined in 1667 by French astronomer Ismael Bouillaud to 333 days, very close to the currently accepted value of 332 days.

Mira got its name, meaning wonderful or astonishing in Latin, from Johannes Hevelius in 1642.

The position of Mira is RA: 02h 19m 21s, Dec: -02° 58′ 39″.

Latest observations of Mira from AAVSO

Bottom line: Mira is a variable star that undergoes periodic changes in brightness every 332 days, ranging from a maximum brightness of around 3.5 visual magnitudes to a minimum brightness of about 9 magnitudes. It’s expected to be brightest in February or March 2026.

Read more: Mira Revisited, from the AAVSO

The post See Mira the Wonderful now and brightest in February or March first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2iK8wMc

Mira the Wonderful

Although stars appear to shine at a constant brilliance, many are variable stars. They brighten and dim over many different timescales. Their changes in brightness are often too small to be perceptible to the unaided eye. But the star Mira, aka Omicron Ceti, is different. Its brightness changes are large and distinctly noticeable to the eye.

Depending on when you look for Mira, this reddish star in the constellation Cetus the Whale might or might not be visible. It goes through its bright-to-faint-to-bright cycle about every 332 days. And Mira is not visible from late March to June because it’s too close to the sun then.

If you’d like to see this unusual star in 2026, now’s your chance.

Mira brightened enough in December 2025 to be visible to the eye in a dark sky. It should reach its maximum brightness in February or March 2026, when it’ll be setting late evening (your local time). Note, it’ll set four minutes earlier each day. Generally, you can see it with the unaided eye for about six weeks before it reaches maximum brightness and over two months afterwards. Of course that depends on when Mira reaches its maximum brightness. In 2026, Mira might still be visible to the eye in a dark sky when it’s lost in the sun’s glare.

Then in 2027, it’s maximum will be in January sometime.

How it got its nickname

Early astronomers noticed this star’s dramatic and regular changes in brightness. Mira sparkles in the sky, getting progressively dimmer, and a few months later, it’s gone! Then, after some months, it’s back again. Its brightness changes led the 17th century astronomer Johannes Hevelius to name the star Mira, from the Latin word for wonderful or astonishing.

So now Mira is on track to hit another brightness peak in February or March 2026. How bright will it get? That’s a question many variable star observers are eagerly waiting to find out. You can check current observations here.

Now you see it, now you don’t

Mira has an average peak brightness of magnitude 3.5. It’s not one of the sky’s brightest stars, even when brightest. It gradually fades to around magnitude 9 (too faint to see with the eye; for reference, in a dark sky, the unaided eye can barely detect a magnitude 6 star). Then it rebounds back to its peak brightness. So Mira undergoes about a 159-fold change in brightness, as it moves through its 332-day brightness cycle.

It’s impossible to predict exactly how bright or faint Mira will become at each maximum. Have a look at the graph below, called a light curve. Mira-watchers contribute their observations to the American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO). The AAVSO creates an ongoing light curve for Mira, using its Light Curve Generator tool. The light curve below covers the last 10 years. The parts of the plot with no data were when Mira was close to the sun. In 2019 and 2022, Mira was as bright as magnitude 2. That’s almost as bright as Polaris, the North Star, not the sky’s brightest star, but a respectably bright star.

How to see Mira

Catch Mira while now while it’s heading toward its brightest! Then keep watching it as it fades away. Its peak brightness for 2026 comes in February or March. At that time, Mira is in the southwest as darkness falls (your local time) and sets a few hours before midnight. However, it’s in the constellation of Cetus which isn’t a prominent constellation. It’s faint. You’ll want a dark sky to see it. If you have a dark sky, you can pick out the Whale’s lopsided pentagon of a Head. Check Stellarium for a precise view and timing from your location.

Look for it again in early 2027

The next upcoming predicted maximum brightnesses for Mira is January or February 2027. Look for Mira around then! That’s when, according to predictions, it should be at its brightest.

Also, look at the chart below. Notice that the distinctive nearby V-shaped Hyades star cluster in Taurus the Bull points to Cetus and its star Mira.

Mira science

Early astronomers marveled at Mira’s brightness changes and considered them a great mystery. But modern astronomers know Mira as a red giant star. It’s slightly more massive than our sun but at least 330 times larger in size. Its huge surface area makes it more than 8,000 times more luminous. Mira is some 300 light-years away. It’s thought to be around 6 billion years old. Mira has a faint white dwarf companion star.

There are many types of pulsating variable stars known today. But Mira was the first of its type discovered. And so, astronomers named an entire class of variable stars after it. Mira variables are stars that have one to a few times the mass of our sun. They’re near the end of their stellar lifetime, at the red giant stage. Mira variables have pulsation periods from 80 to 1,000 days, brightness variations from 2.5 to 10 visual magnitudes, and tend to shed material from their outer layers.

So Mira’s brightness changes aren’t due, for example, to some external factor (such as a disk around the star). They’re caused by the actual expansion and contraction of the entire star, every 332 days. This expansion-contraction oscillation is a complex phenomenon related to changes in the rate that radiation escapes from the star.

Mira’s story is of special interest since our sun will someday follow the same stellar evolutionary path. About 5 billion years from now, our sun will become a Mira variable.

Why Mira’s brightness changes

For much of its existence, Mira converted hydrogen to helium at its core as a main sequence star. When that fuel was exhausted, its core contracted, causing it to heat up. That heating triggered a new round of hydrogen-to-helium nuclear fusion in a shell around the core, causing Mira to balloon in size into a red giant star. Meanwhile, the collapsing core continued to heat up until it became hot enough for the fusion of helium to carbon, and some oxygen.

Mira is currently at a stage in its stellar evolution called the asymptotic giant branch. Its core of carbon and oxygen is inert. However, the star is still actively “burning” a layer of helium around the core, converting it to carbon. And just outside it, a shell of hydrogen is being converted to helium.

The outer layers of Mira are weakly held by gravity and are starting to waft away. Mira will eventually shed its material to form a planetary nebula, with its exposed hot core – a white dwarf star – left behind.

Mira’s 13-light-year-long tail

In 2006, the Galaxy Evolution Explorer telescope obtained ultraviolet images of Mira that surprised scientists. They revealed a long comet-like tail of material trailing the star as it sped through ambient galactic gas. Mira moves through space at about 290,000 miles per hour (466,700 km/h). The tail, about 13 light-years long, is composed of gases and dust released by Mira over the last 30,000 years. The amount of gases and dust in Mira’s tail equal about 3,000 times the Earth’s mass.

Mira in history

Did the earliest stargazers notice Mira as it appeared disappeared and reappeared? If they did, they left no records of this star. The star’s earliest known history begins only 400 years ago, when Dutch astronomer David Fabricius first noticed Mira. That was in the year 1596. He assumed Mira was a nova because, as novae do, the star faded away after a few months. However, Fabricus relocated the star 13 years later. It must have surprised him!

Another Dutch astronomer, Johannes Holwarda, was the first to identify Mira as a variable star, and determined a period of 11 months. That value was refined in 1667 by French astronomer Ismael Bouillaud to 333 days, very close to the currently accepted value of 332 days.

Mira got its name, meaning wonderful or astonishing in Latin, from Johannes Hevelius in 1642.

The position of Mira is RA: 02h 19m 21s, Dec: -02° 58′ 39″.

Latest observations of Mira from AAVSO

Bottom line: Mira is a variable star that undergoes periodic changes in brightness every 332 days, ranging from a maximum brightness of around 3.5 visual magnitudes to a minimum brightness of about 9 magnitudes. It’s expected to be brightest in February or March 2026.

Read more: Mira Revisited, from the AAVSO

The post See Mira the Wonderful now and brightest in February or March first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2iK8wMc

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire