A cool cosmic coincidence kicks off 2026! The first full moon of the year — a supermoon — will coincide with Earth’s closest approach to the sun, known as perihelion, on and around January 2–3. That means the Earth, moon, and sun will all be unusually close and aligned as the new year begins. This rare event hasn’t happened since January 1912 and won’t occur again in our lifetimes. Join us on EarthSky’s livestream at 12 p.m. CST (18 UTC) on Wednesday, December 31, to explore this unique celestial alignment, learn why the seasons don’t follow Earth’s distance from the sun, and see how these subtle cosmic forces shape our sky.

Earth at perihelion in January

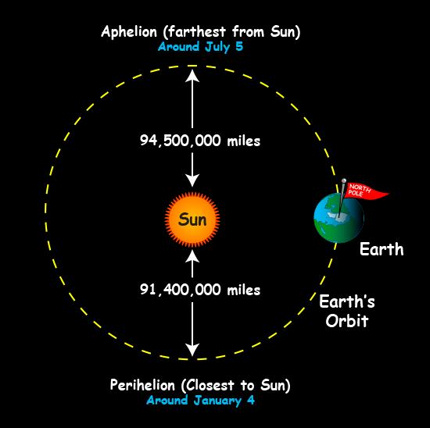

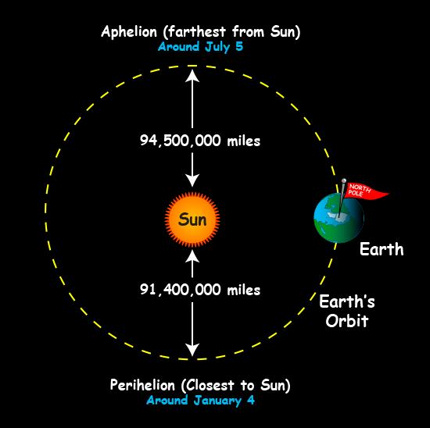

Earth’s orbit around the sun isn’t a circle. Instead, it’s an ellipse, like a circle someone sat down on. So, it makes sense that Earth has closest and farthest points from the sun each year. For 2026, our closest point comes at 17 UTC on January 3 (11 a.m. CST). This closest Earth-sun distance is called perihelion, from the Greek roots peri meaning near and helios meaning sun. At that time, Earth will be 91,403,637 miles (147,099,894 km) from the sun.

In early January, we’re about 3% closer to the sun – roughly 1.5 million miles (2.5 million km) – than we are during Earth’s aphelion (farthest point) in early July. That’s in contrast to our average distance of about 93 million miles (150 million km).

NASA Earth Fact Sheet with precise perihelion and aphelion distances.

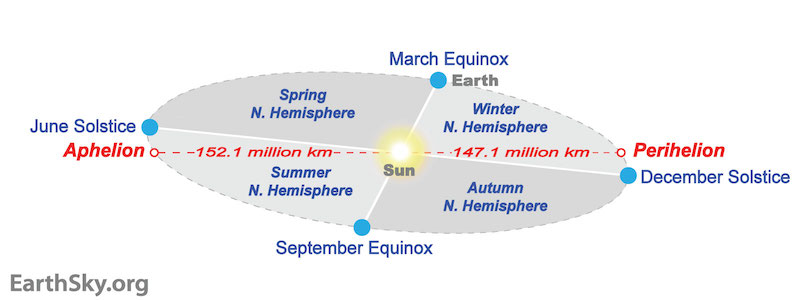

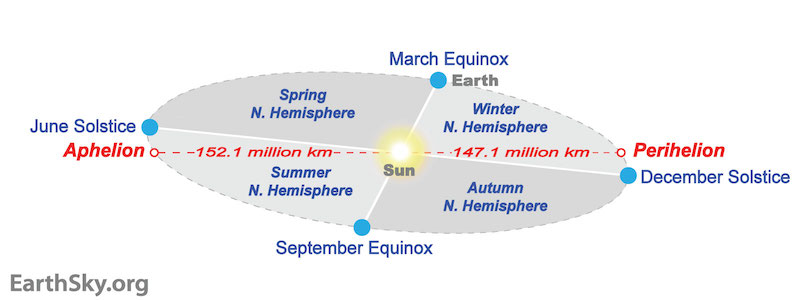

So, Earth is closest to the sun every year in early January, when it’s winter for the Northern Hemisphere.

And we’re farthest away from the sun in early July, during our Northern Hemisphere summer.

Clearly, Earth’s distance from the sun isn’t the cause of the seasons.

Earth’s orbit doesn’t cause seasons

Earth’s orbit isn’t a circle. But it’s nearly circular. And it’s not our distance from the sun that creates winter and summer on Earth. Instead, the tilt of our world’s axis with respect to our orbit causes seasons.

In winter, your part of Earth is tilted away from the sun. In summer, your part of Earth is tilted toward the sun. The day of maximum tilt toward or away from the sun is the December or June solstice.

The tilt changes the angle of sunlight falling on your part of Earth. More direct sunlight = summer. Less direct sunlight = winter.

Earth’s orbit affects length of the seasons

Though not responsible for the seasons, Earth’s closest and farthest points to the sun do affect seasonal lengths. When the Earth comes closest to the sun for the year, as we do every year in early January, our world is moving fastest in orbit. Earth is rushing along now at almost 19 miles per second (30.3 km/s), moving about 0.6 miles per second (1 km/s) faster than when Earth is farthest from the sun in early July. So the Northern Hemisphere winter and – simultaneously – the Southern Hemisphere summer are the shortest seasons, as Earth rushes from the solstice in December to the equinox in March.

In the Northern Hemisphere, the summer season (June solstice to September equinox) lasts nearly five days longer than our winter season. This holds true for the corresponding seasons in the Southern Hemisphere, as well. And the Southern Hemisphere winter is nearly five days longer than the Southern Hemisphere summer.

The 30-second YouTube video below illustrates how a planetary body speeds up around perihelion and slows down at aphelion. It’s due to Kepler’s second law of planetary motion: a line connecting the sun and a planet sweeps out equal areas in equal times.

Bottom line: In 2026, Earth’s closest point to the sun – its perihelion – is on January 3, at 17 UTC. That’s 11 a.m. CST.

The post Earth at perihelion – closest to sun – on January 3 first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/9nqtwFu

A cool cosmic coincidence kicks off 2026! The first full moon of the year — a supermoon — will coincide with Earth’s closest approach to the sun, known as perihelion, on and around January 2–3. That means the Earth, moon, and sun will all be unusually close and aligned as the new year begins. This rare event hasn’t happened since January 1912 and won’t occur again in our lifetimes. Join us on EarthSky’s livestream at 12 p.m. CST (18 UTC) on Wednesday, December 31, to explore this unique celestial alignment, learn why the seasons don’t follow Earth’s distance from the sun, and see how these subtle cosmic forces shape our sky.

Earth at perihelion in January

Earth’s orbit around the sun isn’t a circle. Instead, it’s an ellipse, like a circle someone sat down on. So, it makes sense that Earth has closest and farthest points from the sun each year. For 2026, our closest point comes at 17 UTC on January 3 (11 a.m. CST). This closest Earth-sun distance is called perihelion, from the Greek roots peri meaning near and helios meaning sun. At that time, Earth will be 91,403,637 miles (147,099,894 km) from the sun.

In early January, we’re about 3% closer to the sun – roughly 1.5 million miles (2.5 million km) – than we are during Earth’s aphelion (farthest point) in early July. That’s in contrast to our average distance of about 93 million miles (150 million km).

NASA Earth Fact Sheet with precise perihelion and aphelion distances.

So, Earth is closest to the sun every year in early January, when it’s winter for the Northern Hemisphere.

And we’re farthest away from the sun in early July, during our Northern Hemisphere summer.

Clearly, Earth’s distance from the sun isn’t the cause of the seasons.

Earth’s orbit doesn’t cause seasons

Earth’s orbit isn’t a circle. But it’s nearly circular. And it’s not our distance from the sun that creates winter and summer on Earth. Instead, the tilt of our world’s axis with respect to our orbit causes seasons.

In winter, your part of Earth is tilted away from the sun. In summer, your part of Earth is tilted toward the sun. The day of maximum tilt toward or away from the sun is the December or June solstice.

The tilt changes the angle of sunlight falling on your part of Earth. More direct sunlight = summer. Less direct sunlight = winter.

Earth’s orbit affects length of the seasons

Though not responsible for the seasons, Earth’s closest and farthest points to the sun do affect seasonal lengths. When the Earth comes closest to the sun for the year, as we do every year in early January, our world is moving fastest in orbit. Earth is rushing along now at almost 19 miles per second (30.3 km/s), moving about 0.6 miles per second (1 km/s) faster than when Earth is farthest from the sun in early July. So the Northern Hemisphere winter and – simultaneously – the Southern Hemisphere summer are the shortest seasons, as Earth rushes from the solstice in December to the equinox in March.

In the Northern Hemisphere, the summer season (June solstice to September equinox) lasts nearly five days longer than our winter season. This holds true for the corresponding seasons in the Southern Hemisphere, as well. And the Southern Hemisphere winter is nearly five days longer than the Southern Hemisphere summer.

The 30-second YouTube video below illustrates how a planetary body speeds up around perihelion and slows down at aphelion. It’s due to Kepler’s second law of planetary motion: a line connecting the sun and a planet sweeps out equal areas in equal times.

Bottom line: In 2026, Earth’s closest point to the sun – its perihelion – is on January 3, at 17 UTC. That’s 11 a.m. CST.

The post Earth at perihelion – closest to sun – on January 3 first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/9nqtwFu

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire