The Edmund Fitzgerald sank in Lake Superior during a fierce storm 50 years ago, on November 10, 1975. Superior is known as a lake that never gives up her dead, and there’s a scientific reason why.

It was 50 years ago, on November 10, 1975, that the Great Lakes’ most famous shipwreck claimed the lives of 29 men. SS Edmund Fitzgerald was a 729-foot iron ore freighter that sank during a violent storm in Lake Superior. The tragedy was immortalized in the song “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald” by Gordon Lightfoot. Today, we still think of Lake Superior as the lake that “never gives up her dead.”

A storm for the ages

The Edmund Fitzgerald sailed out of Superior, Wisconsin, on the afternoon of November 9, 1975. It was carrying 29 crew and more than 26,000 tons of taconite pellets. These balls of iron ore concentrate were bound for a steel mill near Detroit.

On November 9, meteorologists issued a gale warning for Lake Superior. The winds were forecast to reach between 34-47 knots (39 and 54 mph). Then, early morning on November 10, forecasters upgraded the gale warning to a storm warning. Forecasters now called for winds of 48 to 55 knots (55-63 mph) and waves of 8 to 15 feet (2.4 to 4.5 meters). But the storm that hit Lake Superior on the 10th ended up having wind gusts of up to 75 knots (86 mph) and waves up to 35 feet (11 meters).

The fate of the Edmund Fitzgerald

Ernest McSorley was the captain of the Edmund Fitzgerald. On that day, he was radioing with other ships in the area about the storm and the battering his ship was taking. At around 3:30 p.m., the captain radioed another ship, the Arthur M. Anderson, and said:

Anderson, this is the Fitzgerald. I have sustained some topside damage. I have a fence rail laid down, two vents lost or damaged, and a list. I’m checking down. Will you stay by me til I get to Whitefish?

About an hour later, McSorley radioed the captain of the Avafors and reported:

I have a bad list, I have lost both radars, and am taking heavy seas over the deck in one of the worst seas I have ever been in.

The final communication came just after 7 p.m. when McSorley radioed the Anderson and said:

We are holding our own.

Not long after that, the ship disappeared from radar off the coast of Whitefish Point, Michigan.

The shipwreck still lies there today, in two pieces, some 530 feet below the surface. No bodies were ever recovered.

Why Lake Superior never gives up her dead

The first three lines of Gordon Lightfoot’s “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald” are:

The legend lives on from the Chippewa on down

Of the big lake, they called Gitche Gumee

The lake, it is said, never gives up her dead

This notion that Lake Superior never gives up her dead is more than just folklore. There’s a scientific reason why the cold lake holds onto its dead.

Lake Superior is the coldest and deepest of the Great Lakes. Its temperatures averages below 40°F (4°C) even in summer. In water that cold, the natural processes of decomposition slow down. In warmer water, when someone drowns, the bacteria in their body create gas that causes them to float to the surface. But in the frigid waters of Lake Superior, bacteria aren’t active. So, without those gases, the bodies will remain at the bottom of the lake.

Not the only graveyard at the bottom of the lake

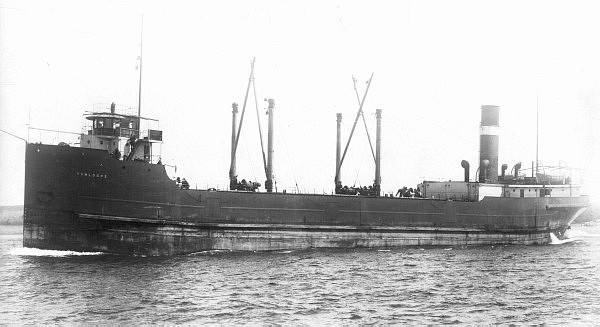

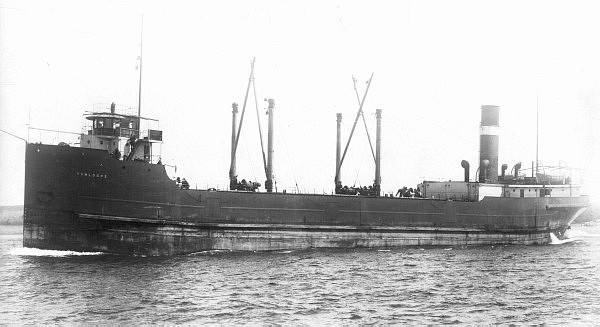

There are some 550 shipwrecks in Lake Superior, and the final resting place of about 200 of them have yet to be discovered. One of those wrecks was SS Kamloops in 1927. Those who went down with the Kamloops are also preserved at the bottom of the cold lake. In 1977, divers discovered the Kamloops off the north shore of Isle Royale. As Geo Rutherford wrote in her book Spooky Lakes:

They looked as fresh as the day they drowned. One crewmate in particular never left his post in the belly of the ship. His corpse, known as ‘Old Whitey,’ floats around the boiler room, where currents from diver’s fins made it seem like the body was following them around the waterlogged space. … The lack of decomposition shocked the divers.

Rutherford explains how bacteria don’t break down in cold water and added:

The cold fresh water can generate a chemical reaction between minerals in the water and human skin that results in a substance called adipocere. The chemical reaction is called ‘saponification,’ which is a process that turns body fat into a soaplike substance … Saponification stops the decay process in its tracks, so a soap mummy can remain intact for potentially hundreds of years …

Bottom line: The sinking of the Edmund Fitzgerald happened 50 years ago, on November 10, 1975. It rests in Lake Superior, known for never giving up her dead. And there’s a scientific reason why.

Read more: Searching for shipwrecks from space

The post The sinking of the Edmund Fitzgerald, 50 years later first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/NuLqc0x

The Edmund Fitzgerald sank in Lake Superior during a fierce storm 50 years ago, on November 10, 1975. Superior is known as a lake that never gives up her dead, and there’s a scientific reason why.

It was 50 years ago, on November 10, 1975, that the Great Lakes’ most famous shipwreck claimed the lives of 29 men. SS Edmund Fitzgerald was a 729-foot iron ore freighter that sank during a violent storm in Lake Superior. The tragedy was immortalized in the song “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald” by Gordon Lightfoot. Today, we still think of Lake Superior as the lake that “never gives up her dead.”

A storm for the ages

The Edmund Fitzgerald sailed out of Superior, Wisconsin, on the afternoon of November 9, 1975. It was carrying 29 crew and more than 26,000 tons of taconite pellets. These balls of iron ore concentrate were bound for a steel mill near Detroit.

On November 9, meteorologists issued a gale warning for Lake Superior. The winds were forecast to reach between 34-47 knots (39 and 54 mph). Then, early morning on November 10, forecasters upgraded the gale warning to a storm warning. Forecasters now called for winds of 48 to 55 knots (55-63 mph) and waves of 8 to 15 feet (2.4 to 4.5 meters). But the storm that hit Lake Superior on the 10th ended up having wind gusts of up to 75 knots (86 mph) and waves up to 35 feet (11 meters).

The fate of the Edmund Fitzgerald

Ernest McSorley was the captain of the Edmund Fitzgerald. On that day, he was radioing with other ships in the area about the storm and the battering his ship was taking. At around 3:30 p.m., the captain radioed another ship, the Arthur M. Anderson, and said:

Anderson, this is the Fitzgerald. I have sustained some topside damage. I have a fence rail laid down, two vents lost or damaged, and a list. I’m checking down. Will you stay by me til I get to Whitefish?

About an hour later, McSorley radioed the captain of the Avafors and reported:

I have a bad list, I have lost both radars, and am taking heavy seas over the deck in one of the worst seas I have ever been in.

The final communication came just after 7 p.m. when McSorley radioed the Anderson and said:

We are holding our own.

Not long after that, the ship disappeared from radar off the coast of Whitefish Point, Michigan.

The shipwreck still lies there today, in two pieces, some 530 feet below the surface. No bodies were ever recovered.

Why Lake Superior never gives up her dead

The first three lines of Gordon Lightfoot’s “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald” are:

The legend lives on from the Chippewa on down

Of the big lake, they called Gitche Gumee

The lake, it is said, never gives up her dead

This notion that Lake Superior never gives up her dead is more than just folklore. There’s a scientific reason why the cold lake holds onto its dead.

Lake Superior is the coldest and deepest of the Great Lakes. Its temperatures averages below 40°F (4°C) even in summer. In water that cold, the natural processes of decomposition slow down. In warmer water, when someone drowns, the bacteria in their body create gas that causes them to float to the surface. But in the frigid waters of Lake Superior, bacteria aren’t active. So, without those gases, the bodies will remain at the bottom of the lake.

Not the only graveyard at the bottom of the lake

There are some 550 shipwrecks in Lake Superior, and the final resting place of about 200 of them have yet to be discovered. One of those wrecks was SS Kamloops in 1927. Those who went down with the Kamloops are also preserved at the bottom of the cold lake. In 1977, divers discovered the Kamloops off the north shore of Isle Royale. As Geo Rutherford wrote in her book Spooky Lakes:

They looked as fresh as the day they drowned. One crewmate in particular never left his post in the belly of the ship. His corpse, known as ‘Old Whitey,’ floats around the boiler room, where currents from diver’s fins made it seem like the body was following them around the waterlogged space. … The lack of decomposition shocked the divers.

Rutherford explains how bacteria don’t break down in cold water and added:

The cold fresh water can generate a chemical reaction between minerals in the water and human skin that results in a substance called adipocere. The chemical reaction is called ‘saponification,’ which is a process that turns body fat into a soaplike substance … Saponification stops the decay process in its tracks, so a soap mummy can remain intact for potentially hundreds of years …

Bottom line: The sinking of the Edmund Fitzgerald happened 50 years ago, on November 10, 1975. It rests in Lake Superior, known for never giving up her dead. And there’s a scientific reason why.

Read more: Searching for shipwrecks from space

The post The sinking of the Edmund Fitzgerald, 50 years later first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/NuLqc0x

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire