Are alcohol and evolution related? Millions of years ago, animals that would eventually evolve into modern humanity ate enough fermented fruit that it altered our genome. And the adaptation stuck. Humans, chimps, bonobos and gorillas can metabolize booze 40 times better than other primates. A team of anthropologists and biologists led by Nathaniel Dominy of Dartmouth University wonder if our love of social drinking led us to develop agriculture and even civilization just so we could brew beer. Dominy joins EarthSky’s Dave Adalian at 12:15 p.m. CDT (17:15 UTC) today to talk about our possibly alcohol-fueled evolution. Watch here or on YouTube.

Alcohol and evolution

Humans and some other great apes share an unusual adaptation: They can metabolize ethyl alcohol – the intoxicating ingredient in beer, wine and cocktail spirits – 40 times more efficiently than other primates.

This genetic change – called the A294V mutation by scientists – gave the last common ancestor of African apes and humans two things: the ability to consume fermented fruits, and a reason to gather in large groups in a relaxed atmosphere. That’s the conclusion of a recently published paper by researchers from the University of St Andrews and Dartmouth College.

The ancient mutation, they said, might be the driving force behind agriculture and civilization:

The significance of this mutation is rather profound, representing, potentially, a signal moment in the history of life on Earth. If the early domestication of cereals revolved around making beer instead of bread, then the A294V mutation was the preadaptation that fueled the Neolithic Revolution and everything that followed.

Why humans and apes can still metabolize booze

The question then becomes one of how the mutation for more effectively metabolizing alcohol survived to the present day. The key, the authors say, was a matter of taste, ease and safety:

The quality, availability, and accessibility of fruit are integral to almost every aspect of ape biology and behavior, and it is practically axiomatic to describe apes as frugivores. It is a classification that rings true even when fruit is scarce, because all apes show a categorical preference for ripening fruit when available …

But that doesn’t explain why large African apes would eat fallen fruit on the ground when there’s still fruit on the trees. Asian apes and most monkeys, by contrast, feed almost exclusively on fruit by climbing up to get it. The authors cite an important previous anthropological work from 2015 to explain why there’s a difference.

Past research on alcohol and evolution

The older work demonstrated gorillas, chimps and bonobos (and humans, too) inherited the critical ability to metabolize booze from a common ancestor that developed it roughly 10 million years ago. That study also speculated that previously these distant ancestors of modern animals starting spending more of their time on the ground during the Middle Miocene period 11.4 million or more years ago, and they simply ran into more fallen fruit. When the mutation came along, it made it possible for animals who had it to take advantage of fruit that was toxic to others. And so they thrived.

The study’s authors put these facts together and reasonably assume that eating perfectly edible fallen fruit was far less dangerous and tiring – and just as rewarding – as trying to get at the fresher stuff. And so early ancestors of humans and modern apes probably relaxed together under fruit trees, eating slightly alcoholic windfall and socializing.

Let the feasting begin

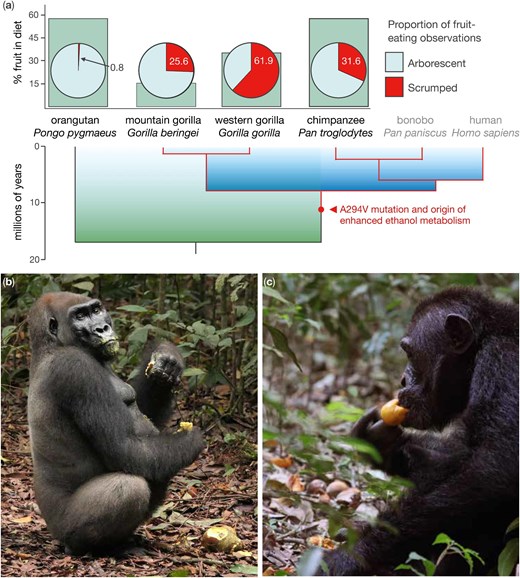

And so happy hour was born somewhere under the boughs of ancient groves where the ground was covered with overripe fruit. It is an idea that seems to make sense given the circumstances of our evolution. But where is the evidence it’s true? The obvious model is the behavior of modern apes. They should still be carrying on this behavior. But the 2025 paper’s authors point out no one had ever checked:

It is a compelling idea that suffers from two problems: the ethanol exposure of African apes is all but unknown, and primatologists seldom differentiate fallen fruits from arborescent ones in their field notes, meaning we have little sense of how often apes consume fruits from the ground. In fact, we don’t even have a word for this behavior.

Lead author Nathaniel Dominy pointed out other anthropologists have used the drunken monkey hypothesis to encapsulate the idea of primates consuming fermented fruit. But, he said, that is likely misleading. His team instead picked an obscure English word – scrumping – to describe the behavior:

Scrumping is the act of gathering – or sometimes stealing – windfallen apples and other fruit. It is an English derivation of the Middle Low German word schrimpen (“shriveled, shrunken”), a medieval noun for describing overripe or fermented fruit. It is an obscure origin perhaps, but its legacy echoes in many British pubs today, where patrons can order scrumpy, a cloudy apple cider with an alcohol by volume content that ranges between 6% and 9%. The adjective scrumptious (something delicious, alluring) alludes to fruit and temptation, a frequent motif in Gothic art and architecture. Indeed, the Gothic tradition recognized scrumping as an essential behavior of nonhuman primates.

Scrumping among the primates

With this new term, they had a way to communicate distinctly with field researchers about exactly what data they needed:

Equipped with this word, we were curious to quantify the frequency of scrumping among great apes. We surveyed dietary reports for orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus), western gorillas (Gorilla gorilla), mountain gorillas (Gorilla beringei), and chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes), cross-referencing fruit-feeding observations with the vertical height of the focal animal or group.

What they found was definitive:

African apes are regular scrumpers …

Editor’s Note: A scrumper is British slang for someone, often a young person, who steals fruit, particularly apples, from a garden or orchard.

Did booze really lead to modern civilization?

And the question of whether alcohol is something apes seek seems to have been answered by another paper on fermented fruit consumption in modern chimps. In April of this year, researchers from the University of Exeter provided evidence of chimps sharing fermented breadfruit on a regular basis. They wonder if the practice might be significant to fostering socialization:

For humans, we know that drinking alcohol leads to a release of dopamine and endorphins, and resulting feelings of happiness and relaxation. We also know that sharing alcohol – including through traditions such as feasting – helps to form and strengthen social bonds. So – now we know that wild chimpanzees are eating and sharing ethanolic fruits – the question is: could they be getting similar benefits?

Dominy and his co-authors conclude their paper with reasons why scrumping was greatly beneficial. It was safer to stay on the ground, and more importantly gave them a feeding advantage among greedy adversaries:

Arboreal monkeys are unapologetic consumers of unripe fruits, exploiting a critical resource during an early stage of development. Such temporal competition is thought to have exerted a strong selective pressure on the cognitive faculties of apes, including tool-use and careful route-planning. Scrumping with a turbocharged ADH4 may have given African apes a similar advantage, yielding access to fruit resources beyond the temporal window preferred by monkeys.

The social aspect, however, may have been even more important for humans:

Co-feeding, and even proactive sharing of high-value foods, including fruit, is common among apes, whereas human co-consumption of alcohol is often integral to feasting and sacred rituals, events that produce and reinforce community identity and cohesion. Is it possible to trace the roots of these human foodways to social scrumping of fermented fruits in the rainforests of Africa?

The research is ongoing to bolster the idea. The next area to explore is finding out how scrumping and the sharing of fermented fruit influences ape society, and thus perhaps influenced our own. Dominy and his team know what questions they must answer:

How does sharing fermented fruits shape the formation and maintenance of social bonds? Does sharing produce social capital for specific individuals, affecting power structures and social relationships? Could regular scrumping influence long-term group stability?

The connection between scrumping fermented fruit and civilization is tenuous, but the evidence is slowly mounting in its favor. As the paper concludes, their new approach – and their new anthropological term, scrumping – may eventually yield a more definitive answer:

Connecting these dots may seem far-fetched, but now we have a word to consider the possibility.

Bottom line: The ability to tolerate alcoholic fruit may have encouraged early hominid socialization. Later, humanity’s love of alcohol may even have driven the rise of agriculture and civilization.

Read more: Microbe-brewery: Favorite fermentation microorganisms

The post Did alcohol and evolution go hand in hand for humanity? first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/7ipGQUW

Are alcohol and evolution related? Millions of years ago, animals that would eventually evolve into modern humanity ate enough fermented fruit that it altered our genome. And the adaptation stuck. Humans, chimps, bonobos and gorillas can metabolize booze 40 times better than other primates. A team of anthropologists and biologists led by Nathaniel Dominy of Dartmouth University wonder if our love of social drinking led us to develop agriculture and even civilization just so we could brew beer. Dominy joins EarthSky’s Dave Adalian at 12:15 p.m. CDT (17:15 UTC) today to talk about our possibly alcohol-fueled evolution. Watch here or on YouTube.

Alcohol and evolution

Humans and some other great apes share an unusual adaptation: They can metabolize ethyl alcohol – the intoxicating ingredient in beer, wine and cocktail spirits – 40 times more efficiently than other primates.

This genetic change – called the A294V mutation by scientists – gave the last common ancestor of African apes and humans two things: the ability to consume fermented fruits, and a reason to gather in large groups in a relaxed atmosphere. That’s the conclusion of a recently published paper by researchers from the University of St Andrews and Dartmouth College.

The ancient mutation, they said, might be the driving force behind agriculture and civilization:

The significance of this mutation is rather profound, representing, potentially, a signal moment in the history of life on Earth. If the early domestication of cereals revolved around making beer instead of bread, then the A294V mutation was the preadaptation that fueled the Neolithic Revolution and everything that followed.

Why humans and apes can still metabolize booze

The question then becomes one of how the mutation for more effectively metabolizing alcohol survived to the present day. The key, the authors say, was a matter of taste, ease and safety:

The quality, availability, and accessibility of fruit are integral to almost every aspect of ape biology and behavior, and it is practically axiomatic to describe apes as frugivores. It is a classification that rings true even when fruit is scarce, because all apes show a categorical preference for ripening fruit when available …

But that doesn’t explain why large African apes would eat fallen fruit on the ground when there’s still fruit on the trees. Asian apes and most monkeys, by contrast, feed almost exclusively on fruit by climbing up to get it. The authors cite an important previous anthropological work from 2015 to explain why there’s a difference.

Past research on alcohol and evolution

The older work demonstrated gorillas, chimps and bonobos (and humans, too) inherited the critical ability to metabolize booze from a common ancestor that developed it roughly 10 million years ago. That study also speculated that previously these distant ancestors of modern animals starting spending more of their time on the ground during the Middle Miocene period 11.4 million or more years ago, and they simply ran into more fallen fruit. When the mutation came along, it made it possible for animals who had it to take advantage of fruit that was toxic to others. And so they thrived.

The study’s authors put these facts together and reasonably assume that eating perfectly edible fallen fruit was far less dangerous and tiring – and just as rewarding – as trying to get at the fresher stuff. And so early ancestors of humans and modern apes probably relaxed together under fruit trees, eating slightly alcoholic windfall and socializing.

Let the feasting begin

And so happy hour was born somewhere under the boughs of ancient groves where the ground was covered with overripe fruit. It is an idea that seems to make sense given the circumstances of our evolution. But where is the evidence it’s true? The obvious model is the behavior of modern apes. They should still be carrying on this behavior. But the 2025 paper’s authors point out no one had ever checked:

It is a compelling idea that suffers from two problems: the ethanol exposure of African apes is all but unknown, and primatologists seldom differentiate fallen fruits from arborescent ones in their field notes, meaning we have little sense of how often apes consume fruits from the ground. In fact, we don’t even have a word for this behavior.

Lead author Nathaniel Dominy pointed out other anthropologists have used the drunken monkey hypothesis to encapsulate the idea of primates consuming fermented fruit. But, he said, that is likely misleading. His team instead picked an obscure English word – scrumping – to describe the behavior:

Scrumping is the act of gathering – or sometimes stealing – windfallen apples and other fruit. It is an English derivation of the Middle Low German word schrimpen (“shriveled, shrunken”), a medieval noun for describing overripe or fermented fruit. It is an obscure origin perhaps, but its legacy echoes in many British pubs today, where patrons can order scrumpy, a cloudy apple cider with an alcohol by volume content that ranges between 6% and 9%. The adjective scrumptious (something delicious, alluring) alludes to fruit and temptation, a frequent motif in Gothic art and architecture. Indeed, the Gothic tradition recognized scrumping as an essential behavior of nonhuman primates.

Scrumping among the primates

With this new term, they had a way to communicate distinctly with field researchers about exactly what data they needed:

Equipped with this word, we were curious to quantify the frequency of scrumping among great apes. We surveyed dietary reports for orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus), western gorillas (Gorilla gorilla), mountain gorillas (Gorilla beringei), and chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes), cross-referencing fruit-feeding observations with the vertical height of the focal animal or group.

What they found was definitive:

African apes are regular scrumpers …

Editor’s Note: A scrumper is British slang for someone, often a young person, who steals fruit, particularly apples, from a garden or orchard.

Did booze really lead to modern civilization?

And the question of whether alcohol is something apes seek seems to have been answered by another paper on fermented fruit consumption in modern chimps. In April of this year, researchers from the University of Exeter provided evidence of chimps sharing fermented breadfruit on a regular basis. They wonder if the practice might be significant to fostering socialization:

For humans, we know that drinking alcohol leads to a release of dopamine and endorphins, and resulting feelings of happiness and relaxation. We also know that sharing alcohol – including through traditions such as feasting – helps to form and strengthen social bonds. So – now we know that wild chimpanzees are eating and sharing ethanolic fruits – the question is: could they be getting similar benefits?

Dominy and his co-authors conclude their paper with reasons why scrumping was greatly beneficial. It was safer to stay on the ground, and more importantly gave them a feeding advantage among greedy adversaries:

Arboreal monkeys are unapologetic consumers of unripe fruits, exploiting a critical resource during an early stage of development. Such temporal competition is thought to have exerted a strong selective pressure on the cognitive faculties of apes, including tool-use and careful route-planning. Scrumping with a turbocharged ADH4 may have given African apes a similar advantage, yielding access to fruit resources beyond the temporal window preferred by monkeys.

The social aspect, however, may have been even more important for humans:

Co-feeding, and even proactive sharing of high-value foods, including fruit, is common among apes, whereas human co-consumption of alcohol is often integral to feasting and sacred rituals, events that produce and reinforce community identity and cohesion. Is it possible to trace the roots of these human foodways to social scrumping of fermented fruits in the rainforests of Africa?

The research is ongoing to bolster the idea. The next area to explore is finding out how scrumping and the sharing of fermented fruit influences ape society, and thus perhaps influenced our own. Dominy and his team know what questions they must answer:

How does sharing fermented fruits shape the formation and maintenance of social bonds? Does sharing produce social capital for specific individuals, affecting power structures and social relationships? Could regular scrumping influence long-term group stability?

The connection between scrumping fermented fruit and civilization is tenuous, but the evidence is slowly mounting in its favor. As the paper concludes, their new approach – and their new anthropological term, scrumping – may eventually yield a more definitive answer:

Connecting these dots may seem far-fetched, but now we have a word to consider the possibility.

Bottom line: The ability to tolerate alcoholic fruit may have encouraged early hominid socialization. Later, humanity’s love of alcohol may even have driven the rise of agriculture and civilization.

Read more: Microbe-brewery: Favorite fermentation microorganisms

The post Did alcohol and evolution go hand in hand for humanity? first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/7ipGQUW

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire