Did sunscreen help ancient humans when Earth’s magnetic field grew dangerously thin some 41,000 years ago? EarthSky’s Will Triggs speaks with scientist Agnit Mukhopadhyay about a time 41,000 years ago when Earth’s magnetic poles went wandering. Watch in the player above or on YouTube.

When Earth’s poles shifted …

When Earth’s magnetic field grew dangerously thin some 41,000 years ago, early humans might have used a natural clay – ocher – as a sunscreen to help them survive the sun’s radiation and outlive the Neanderthals. So says a new study into the Laschamps event, a roughly two-millennia period in which Earth’s magnetic poles shifted rapidly across the globe.

Scientists from the University of Michigan said on April 16, 2025, that this shift allowed vivid auroras to be seen night after night across Earth, extending as far south as the equator. But it also meant that dangerous levels of ultraviolet radiation were able to pass through Earth’s atmosphere. And around that same time – 41,000 years ago – early humans appear to have done other things, besides using ocher, to protect themselves from the sun’s harmful rays. They started spending more time in caves. And they began tailoring sun-protective clothing.

The researchers published their peer-reviewed findings in the journal Science Advances on April 16, 2025.

Earth’s magnetic poles aren’t fixed

Our planet is encased in an invisible protective bubble. This global magnetic field, which shields us from cosmic radiation and charged solar particles, is generated by the motion of molten metals in Earth’s outer core. As the metals flow, they create electrical currents, which in turn produces a global magnetic field with one pole near our planet’s geographic North Pole, and one around the South Pole.

But these magnetic poles aren’t static. Earth’s magnetic North Pole is currently moving toward Siberia at around 35 kilometers (22 miles) a year. And roughly every 300,000 years, these poles swap places entirely. This is called a geomagnetic reversal, and it’s happened 183 times in the last 83 million years.

On some occasions, a pole reversal begins but isn’t quite completed. Known as a geomagnetic excursion, these events see the poles move vast distances around the globe on human timescales, before returning to their original orientation within as little as hundreds of years.

The Laschamps event was the most recent confirmed geomagnetic excursion. It occurred when ancient humans were coexisting in Europe with Neanderthals. And scientists have just mapped this event in unprecedented detail.

Mapping the Laschamps event

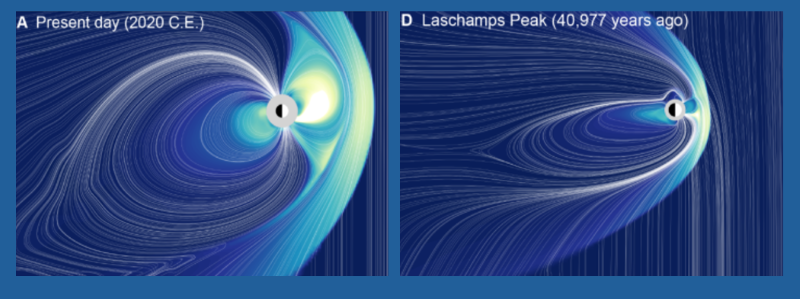

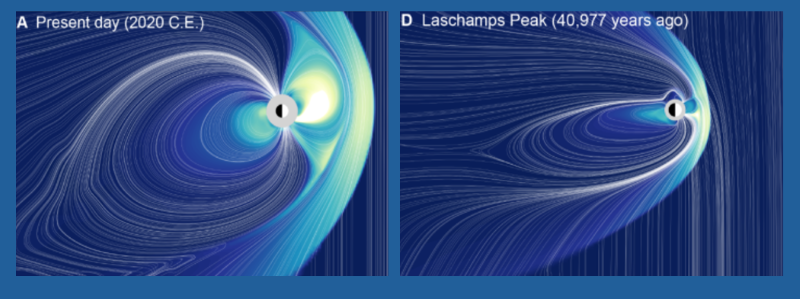

To find new insights into the Laschamps event – likely the most well-studied geomagnetic excursion – the researchers combined 3 models. One reconstructed the global geomagnetic field during the excursion, another modeled the wider space environment around Earth – the magnetosphere – and another predicted auroral coverage during the period.

The resulting 3D model revealed that our planet’s auroral ovals – the rings around the North and South poles where auroras are most likely to occur – would have plunged towards the equator. With the magnetic North Pole dropping as far south as the Sahara Desert, vivid light displays would have been visible across the globe in this period.

Auroral ovals consist largely of so-called open magnetic field lines. Unlike closed lines, which loop from one hemisphere to the other, these lines stretch out from one pole into space, where they connect to the sun’s magnetic field. Charged solar particles are pulled along open lines toward Earth’s poles, where they react with our atmosphere to create auroras. And during the Laschamps excursion, far more of Earth’s magnetic field lines were open.

This is because the strength of the magnetic field plummeted. At the peak of the excursion, it dropped to just 10% of its current strength. And this meant a huge increase in cosmic radiation and solar particles penetrating Earth’s atmosphere, particularly in these auroral ovals.

This influx of radiation would have started to strip away our planet’s ozone layer. And that means for the roughly 1,800 years the Laschamps event was felt on Earth’s surface, life on our planet was exposed to a dangerous onslaught of ultraviolet radiation.

Did sunscreen help ancient humans?

Intriguingly, researchers have identified changes in human behavior around this time. For instance, Homo sapiens started to spend more time in caves, away from sunlight. And the period saw an increased use of ochre: a naturally occurring mineral that protects against ultraviolet radiation when applied to the skin, and which human communities have historically used for that purpose.

The scientists mapped archaeological records of these behaviours onto their new model of Earth during the Laschamps event. And they found that these behaviours occurred mainly within the auroral ovals. That is, signs of ochre use and cave dwelling were found in areas where humans would have been most affected by the increased radiation. Study lead Agnit Mukhopadhyay explained:

In the study, we combined all of the regions where the magnetic field would not have been connected, allowing cosmic radiation, or any kind of energetic particles from the sun, to seep all the way in to the ground. We found that many of those regions actually match pretty closely with early human activity from 41,000 years ago, specifically an increase in the use of caves and an increase in the use of prehistoric sunscreen.

Similarly, archaeologists have found tools from these sites which appear designed to make closely tailored clothing. The researchers noted that not only would tailored clothes have provided increased warmth, but they might have provided the unintended benefit of sun protection.

Neanderthals might have struggled to adapt

Whether intentional or not, behaviours that limited sun exposure would have been hugely beneficial at this time, when ultraviolet radiation levels were high enough to cause birth defects and cancers. Anthropologist and study co-author Raven Garvey surmised:

Having protection against solar radiation would have conferred significant advantage to anyone who possessed it.

And it seems, potentially, that this was an advantage our ancestors held over the Neanderthals. Archaeologists have not found evidence that Neanderthals, our evolutionary rivals, adopted ochre or tailored clothing around this time. And a thousand years later, at the end of the Laschamps event, they had become extinct.

The researchers are keen to note that this is only a correlation; it’s not possible with current evidence to say that this was a direct cause of the Neanderthal extinction. But it’s a potentially enlightening piece to add to the puzzle. Mukhopadhyay told EarthSky:

The extinction of any species is a multifaceted problem. All that we can say is that this definitely had a hand in exacerbating the effects.

What if this happens today?

As well as helping us understand how our ancestors might have managed to survived on a changing world, the study could also help us predict how a similar event might affect us in the future.

Although it’s often said that we are ‘overdue’ a pole reversal, scientists aren’t expecting this to occur any time soon. But if our poles were to wander as much as they did during the Laschamps event, our current infrastructure would be severely affected, Mukhopadhyay warns:

If such an event were to happen today, we would see a complete blackout in several different sectors. Our communication satellites would not work. Many of our telecommunication arrays, which are on the ground, would be severely affected by the smallest of space weather events, not to mention the human impacts which would also play a pretty massive role in our day-to-day lives.

In this future, sunscreen would perhaps be the least of our concerns. But it might have been crucial to the survival of our ancestors 41,000 years ago.

Bottom line: Did sunscreen help ancient humans when Earth’s magnetic field grew dangerously thin some 41,000 years ago? A new study suggests it did.

Source: Wandering of the auroral oval 41,000 years ago

Read more: Creepy sound of Earth’s magnetic field flip: Listen here!

Read more: Magnetic pole flip on Earth? Probably not soon

The post Did sunscreen help ancient humans survive a pole shift? first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/xX5hWD1

Did sunscreen help ancient humans when Earth’s magnetic field grew dangerously thin some 41,000 years ago? EarthSky’s Will Triggs speaks with scientist Agnit Mukhopadhyay about a time 41,000 years ago when Earth’s magnetic poles went wandering. Watch in the player above or on YouTube.

When Earth’s poles shifted …

When Earth’s magnetic field grew dangerously thin some 41,000 years ago, early humans might have used a natural clay – ocher – as a sunscreen to help them survive the sun’s radiation and outlive the Neanderthals. So says a new study into the Laschamps event, a roughly two-millennia period in which Earth’s magnetic poles shifted rapidly across the globe.

Scientists from the University of Michigan said on April 16, 2025, that this shift allowed vivid auroras to be seen night after night across Earth, extending as far south as the equator. But it also meant that dangerous levels of ultraviolet radiation were able to pass through Earth’s atmosphere. And around that same time – 41,000 years ago – early humans appear to have done other things, besides using ocher, to protect themselves from the sun’s harmful rays. They started spending more time in caves. And they began tailoring sun-protective clothing.

The researchers published their peer-reviewed findings in the journal Science Advances on April 16, 2025.

Earth’s magnetic poles aren’t fixed

Our planet is encased in an invisible protective bubble. This global magnetic field, which shields us from cosmic radiation and charged solar particles, is generated by the motion of molten metals in Earth’s outer core. As the metals flow, they create electrical currents, which in turn produces a global magnetic field with one pole near our planet’s geographic North Pole, and one around the South Pole.

But these magnetic poles aren’t static. Earth’s magnetic North Pole is currently moving toward Siberia at around 35 kilometers (22 miles) a year. And roughly every 300,000 years, these poles swap places entirely. This is called a geomagnetic reversal, and it’s happened 183 times in the last 83 million years.

On some occasions, a pole reversal begins but isn’t quite completed. Known as a geomagnetic excursion, these events see the poles move vast distances around the globe on human timescales, before returning to their original orientation within as little as hundreds of years.

The Laschamps event was the most recent confirmed geomagnetic excursion. It occurred when ancient humans were coexisting in Europe with Neanderthals. And scientists have just mapped this event in unprecedented detail.

Mapping the Laschamps event

To find new insights into the Laschamps event – likely the most well-studied geomagnetic excursion – the researchers combined 3 models. One reconstructed the global geomagnetic field during the excursion, another modeled the wider space environment around Earth – the magnetosphere – and another predicted auroral coverage during the period.

The resulting 3D model revealed that our planet’s auroral ovals – the rings around the North and South poles where auroras are most likely to occur – would have plunged towards the equator. With the magnetic North Pole dropping as far south as the Sahara Desert, vivid light displays would have been visible across the globe in this period.

Auroral ovals consist largely of so-called open magnetic field lines. Unlike closed lines, which loop from one hemisphere to the other, these lines stretch out from one pole into space, where they connect to the sun’s magnetic field. Charged solar particles are pulled along open lines toward Earth’s poles, where they react with our atmosphere to create auroras. And during the Laschamps excursion, far more of Earth’s magnetic field lines were open.

This is because the strength of the magnetic field plummeted. At the peak of the excursion, it dropped to just 10% of its current strength. And this meant a huge increase in cosmic radiation and solar particles penetrating Earth’s atmosphere, particularly in these auroral ovals.

This influx of radiation would have started to strip away our planet’s ozone layer. And that means for the roughly 1,800 years the Laschamps event was felt on Earth’s surface, life on our planet was exposed to a dangerous onslaught of ultraviolet radiation.

Did sunscreen help ancient humans?

Intriguingly, researchers have identified changes in human behavior around this time. For instance, Homo sapiens started to spend more time in caves, away from sunlight. And the period saw an increased use of ochre: a naturally occurring mineral that protects against ultraviolet radiation when applied to the skin, and which human communities have historically used for that purpose.

The scientists mapped archaeological records of these behaviours onto their new model of Earth during the Laschamps event. And they found that these behaviours occurred mainly within the auroral ovals. That is, signs of ochre use and cave dwelling were found in areas where humans would have been most affected by the increased radiation. Study lead Agnit Mukhopadhyay explained:

In the study, we combined all of the regions where the magnetic field would not have been connected, allowing cosmic radiation, or any kind of energetic particles from the sun, to seep all the way in to the ground. We found that many of those regions actually match pretty closely with early human activity from 41,000 years ago, specifically an increase in the use of caves and an increase in the use of prehistoric sunscreen.

Similarly, archaeologists have found tools from these sites which appear designed to make closely tailored clothing. The researchers noted that not only would tailored clothes have provided increased warmth, but they might have provided the unintended benefit of sun protection.

Neanderthals might have struggled to adapt

Whether intentional or not, behaviours that limited sun exposure would have been hugely beneficial at this time, when ultraviolet radiation levels were high enough to cause birth defects and cancers. Anthropologist and study co-author Raven Garvey surmised:

Having protection against solar radiation would have conferred significant advantage to anyone who possessed it.

And it seems, potentially, that this was an advantage our ancestors held over the Neanderthals. Archaeologists have not found evidence that Neanderthals, our evolutionary rivals, adopted ochre or tailored clothing around this time. And a thousand years later, at the end of the Laschamps event, they had become extinct.

The researchers are keen to note that this is only a correlation; it’s not possible with current evidence to say that this was a direct cause of the Neanderthal extinction. But it’s a potentially enlightening piece to add to the puzzle. Mukhopadhyay told EarthSky:

The extinction of any species is a multifaceted problem. All that we can say is that this definitely had a hand in exacerbating the effects.

What if this happens today?

As well as helping us understand how our ancestors might have managed to survived on a changing world, the study could also help us predict how a similar event might affect us in the future.

Although it’s often said that we are ‘overdue’ a pole reversal, scientists aren’t expecting this to occur any time soon. But if our poles were to wander as much as they did during the Laschamps event, our current infrastructure would be severely affected, Mukhopadhyay warns:

If such an event were to happen today, we would see a complete blackout in several different sectors. Our communication satellites would not work. Many of our telecommunication arrays, which are on the ground, would be severely affected by the smallest of space weather events, not to mention the human impacts which would also play a pretty massive role in our day-to-day lives.

In this future, sunscreen would perhaps be the least of our concerns. But it might have been crucial to the survival of our ancestors 41,000 years ago.

Bottom line: Did sunscreen help ancient humans when Earth’s magnetic field grew dangerously thin some 41,000 years ago? A new study suggests it did.

Source: Wandering of the auroral oval 41,000 years ago

Read more: Creepy sound of Earth’s magnetic field flip: Listen here!

Read more: Magnetic pole flip on Earth? Probably not soon

The post Did sunscreen help ancient humans survive a pole shift? first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/xX5hWD1

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire