The search for habitable exoplanets

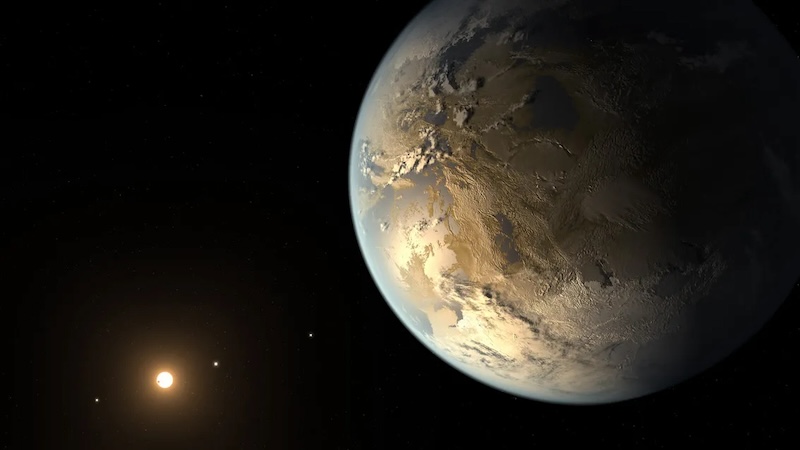

Searching for habitable exoplanets, or even evidence of life itself, is by no means an easy task. In particular, detecting possible biosignatures – chemical traces of life in atmospheres – is painstaking. Now, there is a new way that scientists can determine if an exoplanet may be at least potentially habitable. On December 28, 2023, an international team of scientists said a good strategy might be to look for a lower-than-expected abundance of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere of a rocky planet. This could indicate the presence of liquid water and a habitable environment.

The research team, co-led by researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and the University of Birmingham in the U.K., published their peer-reviewed findings in Nature Astronomy on December 28, 2023. You can also read a free preprint version of the paper on arXiv.

Co-lead author Julien de Wit at MIT stated:

The Holy Grail in exoplanet science is to look for habitable worlds, and the presence of life, but all the features that have been talked about so far have been beyond the reach of the newest observatories. Now we have a way to find out if there’s liquid water on another planet. And it’s something we can get to in the next few years.

The 2024 lunar calendars are here! Best New Year’s gifts in the universe! Check ’em out here.

Lack of carbon dioxide could indicate liquid water

In our solar system, Venus, Earth and Mars all have carbon dioxide in their atmospheres. Notably, however, Earth has much less carbon dioxide, percentage-wise. (Even though Mars’ atmosphere is much thinner, it is still primarily composed of carbon dioxide). The researchers also noted that Earth is the only one of the three to have liquid water on its surface. They propose there is a connection between that and the less abundant carbon dioxide. Hence, habitable exoplanets with reduced amounts of carbon dioxide could also be more likely to have liquid water.

Co-lead author Amaury Triaud of the University of Birmingham said:

An idea came to us, by looking at what’s going on with the terrestrial planets in our own system.

De Wit added:

We assume that these planets were created in a similar fashion, and if we see one planet with much less carbon now, it must have gone somewhere. The only process that could remove that much carbon from an atmosphere is a strong water cycle involving oceans of liquid water.

The paper further stated:

The conventional observables to identify a habitable or inhabited environment in exoplanets, such as an ocean glint or abundant atmospheric O2, will be challenging to detect with present or upcoming observatories. Here we suggest a new signature. A low carbon abundance in the atmosphere of a temperate rocky planet, relative to other planets of the same system, traces the presence of a substantial amount of liquid water, plate tectonics and/or biomass.

Earth as an analog for habitable exoplanets

On Earth, the oceans absorb carbon dioxide. In fact, they have absorbed almost as much carbon dioxide that exists in Venus’ atmosphere, over hundreds of millions of years. This means that our planet now has much less carbon dioxide in its atmosphere than it once did. As co-author Frieder Klein at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts said:

On Earth, much of the atmospheric carbon dioxide has been sequestered in seawater and solid rock over geological timescales, which has helped to regulate climate and habitability for billions of years.

The idea then is that if astronomers found a rocky exoplanet with a similar depletion of carbon dioxide, that could be a good indicator of oceans and possibly even life on the planet. De Wit said:

After reviewing extensively the literature of many fields from biology, to chemistry, and even carbon sequestration in the context of climate change, we believe that indeed if we detect carbon depletion, it has a good chance of being a strong sign of liquid water and/or life.

What about life itself?

So how would scientists look for such carbon-depleted worlds? And would it be possible to find signs of life? Even if a planet is habitable, by earthly standards, that doesn’t necessarily mean it is inhabited.

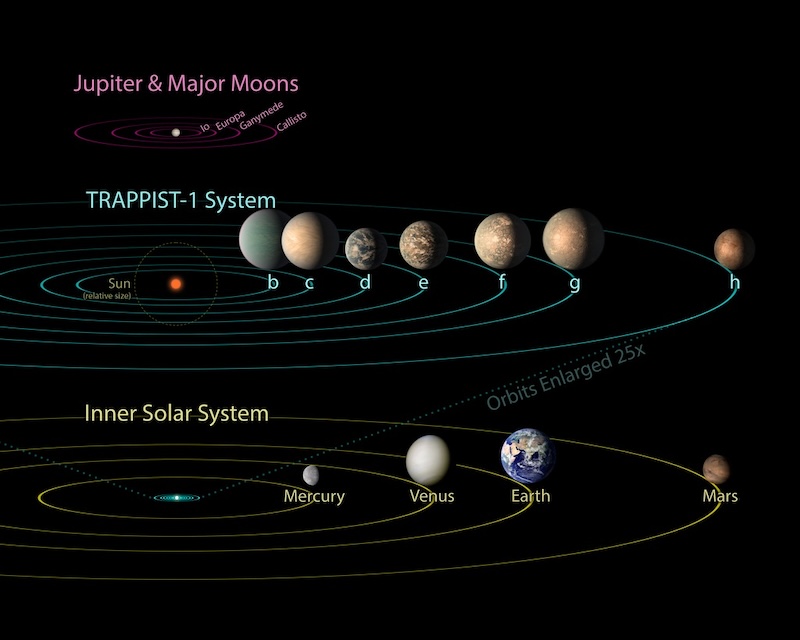

The researchers say that the first step is to focus on peas-in-a-pod planetary systems. Those are ones that have multiple rocky planets relatively close to each other. In our own solar system, Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars are peas in a pod. TRAPPIST-1, only 40 light-years away, is a good example of such a system, with seven rocky planets, all close in size to Earth and with fairly close orbits.

Astronomers can then compare the planets and their atmospheres, if they have them, to see if any have significantly less carbon dioxide than the others. If any of them do, then, as described above, there is a good chance that they have oceans and may be habitable. Luckily, carbon dioxide is easy to detect in exoplanetary atmospheres, as de Wit noted:

Carbon dioxide is a very strong absorber in the infrared, and can be easily detected in the atmospheres of exoplanets. A signal of carbon dioxide can then reveal the presence of exoplanet atmospheres.

Look for ozone, too

That’s still not enough, however, to prove there is life on the planet. That is a more difficult task, but there is something else that astronomers can look for: ozone.

We said that oceans absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Well, so do plants and even some kinds of microbes. As a by-product they release oxygen, which on Earth is what more advanced lifeforms breathe, including humans. Then, that oxygen reacts with photons from the sun to create ozone. If a planet had reduced carbon dioxide alone, then it would still be hard to determine if it’s inhabited by any kind of life. But if it had reduced carbon dioxide and ozone, then the chances that it hosts life go up significantly. Triaud explained:

If we see ozone, chances are pretty high that it’s connected to carbon dioxide being consumed by life. And if it’s life, it’s glorious life. It would not be just a few bacteria. It would be a planetary-scale biomass that’s able to process a huge amount of carbon, and interact with it.

A new roadmap

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) will be able to analyze the atmospheres of some nearby rocky planets, such as in the TRAPPIST-1 system, for both carbon dioxide and ozone. De Wit said:

TRAPPIST-1 is one of only a handful of systems where we could do terrestrial atmospheric studies with the JWST. Now we have a roadmap for finding habitable planets. If we all work together, paradigm-shifting discoveries could be done within the next few years.

Bottom line: A new study says that rocky habitable exoplanets likely have less carbon dioxide in their atmospheres as compared to similar planets in the same system.

Read more: Searching for habitable exoplanets? Look for phosphorus

Read more: Are the TRAPPIST-1 exoplanets habitable, or not?

The post Habitable exoplanets may have less carbon dioxide first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/gOEevj8

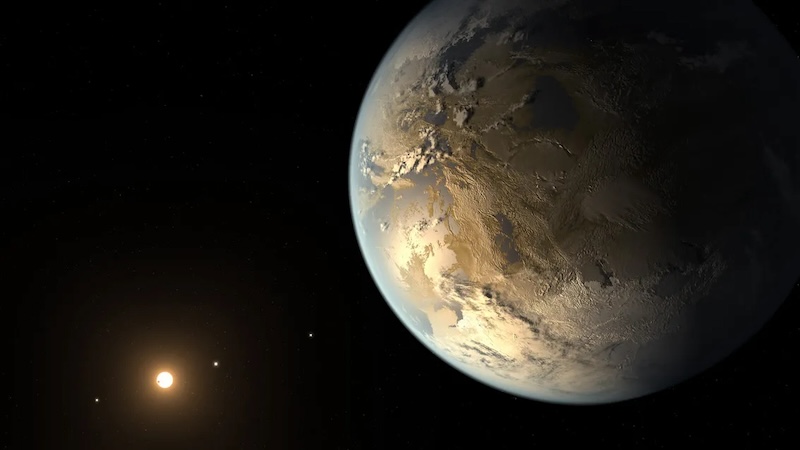

The search for habitable exoplanets

Searching for habitable exoplanets, or even evidence of life itself, is by no means an easy task. In particular, detecting possible biosignatures – chemical traces of life in atmospheres – is painstaking. Now, there is a new way that scientists can determine if an exoplanet may be at least potentially habitable. On December 28, 2023, an international team of scientists said a good strategy might be to look for a lower-than-expected abundance of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere of a rocky planet. This could indicate the presence of liquid water and a habitable environment.

The research team, co-led by researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and the University of Birmingham in the U.K., published their peer-reviewed findings in Nature Astronomy on December 28, 2023. You can also read a free preprint version of the paper on arXiv.

Co-lead author Julien de Wit at MIT stated:

The Holy Grail in exoplanet science is to look for habitable worlds, and the presence of life, but all the features that have been talked about so far have been beyond the reach of the newest observatories. Now we have a way to find out if there’s liquid water on another planet. And it’s something we can get to in the next few years.

The 2024 lunar calendars are here! Best New Year’s gifts in the universe! Check ’em out here.

Lack of carbon dioxide could indicate liquid water

In our solar system, Venus, Earth and Mars all have carbon dioxide in their atmospheres. Notably, however, Earth has much less carbon dioxide, percentage-wise. (Even though Mars’ atmosphere is much thinner, it is still primarily composed of carbon dioxide). The researchers also noted that Earth is the only one of the three to have liquid water on its surface. They propose there is a connection between that and the less abundant carbon dioxide. Hence, habitable exoplanets with reduced amounts of carbon dioxide could also be more likely to have liquid water.

Co-lead author Amaury Triaud of the University of Birmingham said:

An idea came to us, by looking at what’s going on with the terrestrial planets in our own system.

De Wit added:

We assume that these planets were created in a similar fashion, and if we see one planet with much less carbon now, it must have gone somewhere. The only process that could remove that much carbon from an atmosphere is a strong water cycle involving oceans of liquid water.

The paper further stated:

The conventional observables to identify a habitable or inhabited environment in exoplanets, such as an ocean glint or abundant atmospheric O2, will be challenging to detect with present or upcoming observatories. Here we suggest a new signature. A low carbon abundance in the atmosphere of a temperate rocky planet, relative to other planets of the same system, traces the presence of a substantial amount of liquid water, plate tectonics and/or biomass.

Earth as an analog for habitable exoplanets

On Earth, the oceans absorb carbon dioxide. In fact, they have absorbed almost as much carbon dioxide that exists in Venus’ atmosphere, over hundreds of millions of years. This means that our planet now has much less carbon dioxide in its atmosphere than it once did. As co-author Frieder Klein at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts said:

On Earth, much of the atmospheric carbon dioxide has been sequestered in seawater and solid rock over geological timescales, which has helped to regulate climate and habitability for billions of years.

The idea then is that if astronomers found a rocky exoplanet with a similar depletion of carbon dioxide, that could be a good indicator of oceans and possibly even life on the planet. De Wit said:

After reviewing extensively the literature of many fields from biology, to chemistry, and even carbon sequestration in the context of climate change, we believe that indeed if we detect carbon depletion, it has a good chance of being a strong sign of liquid water and/or life.

What about life itself?

So how would scientists look for such carbon-depleted worlds? And would it be possible to find signs of life? Even if a planet is habitable, by earthly standards, that doesn’t necessarily mean it is inhabited.

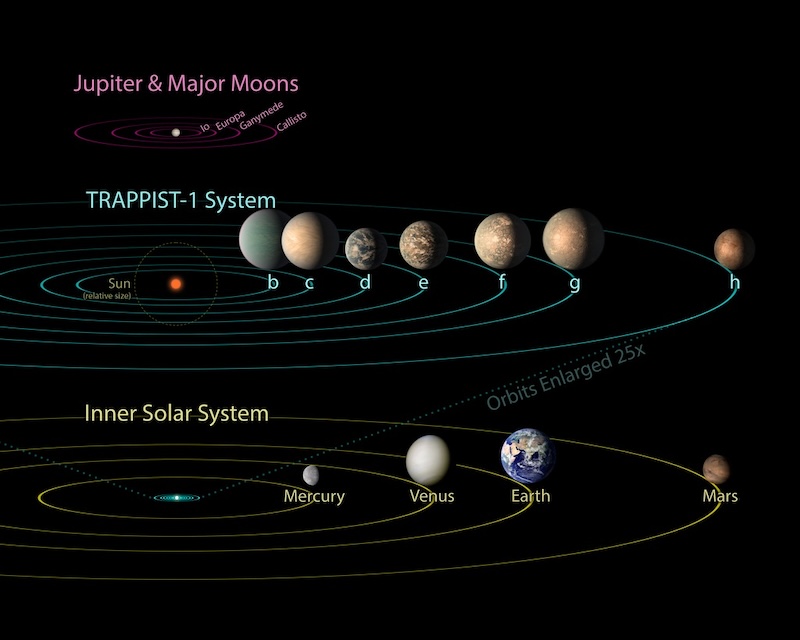

The researchers say that the first step is to focus on peas-in-a-pod planetary systems. Those are ones that have multiple rocky planets relatively close to each other. In our own solar system, Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars are peas in a pod. TRAPPIST-1, only 40 light-years away, is a good example of such a system, with seven rocky planets, all close in size to Earth and with fairly close orbits.

Astronomers can then compare the planets and their atmospheres, if they have them, to see if any have significantly less carbon dioxide than the others. If any of them do, then, as described above, there is a good chance that they have oceans and may be habitable. Luckily, carbon dioxide is easy to detect in exoplanetary atmospheres, as de Wit noted:

Carbon dioxide is a very strong absorber in the infrared, and can be easily detected in the atmospheres of exoplanets. A signal of carbon dioxide can then reveal the presence of exoplanet atmospheres.

Look for ozone, too

That’s still not enough, however, to prove there is life on the planet. That is a more difficult task, but there is something else that astronomers can look for: ozone.

We said that oceans absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Well, so do plants and even some kinds of microbes. As a by-product they release oxygen, which on Earth is what more advanced lifeforms breathe, including humans. Then, that oxygen reacts with photons from the sun to create ozone. If a planet had reduced carbon dioxide alone, then it would still be hard to determine if it’s inhabited by any kind of life. But if it had reduced carbon dioxide and ozone, then the chances that it hosts life go up significantly. Triaud explained:

If we see ozone, chances are pretty high that it’s connected to carbon dioxide being consumed by life. And if it’s life, it’s glorious life. It would not be just a few bacteria. It would be a planetary-scale biomass that’s able to process a huge amount of carbon, and interact with it.

A new roadmap

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) will be able to analyze the atmospheres of some nearby rocky planets, such as in the TRAPPIST-1 system, for both carbon dioxide and ozone. De Wit said:

TRAPPIST-1 is one of only a handful of systems where we could do terrestrial atmospheric studies with the JWST. Now we have a roadmap for finding habitable planets. If we all work together, paradigm-shifting discoveries could be done within the next few years.

Bottom line: A new study says that rocky habitable exoplanets likely have less carbon dioxide in their atmospheres as compared to similar planets in the same system.

Read more: Searching for habitable exoplanets? Look for phosphorus

Read more: Are the TRAPPIST-1 exoplanets habitable, or not?

The post Habitable exoplanets may have less carbon dioxide first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/gOEevj8

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire