Cassiopeia the Queen in autumn

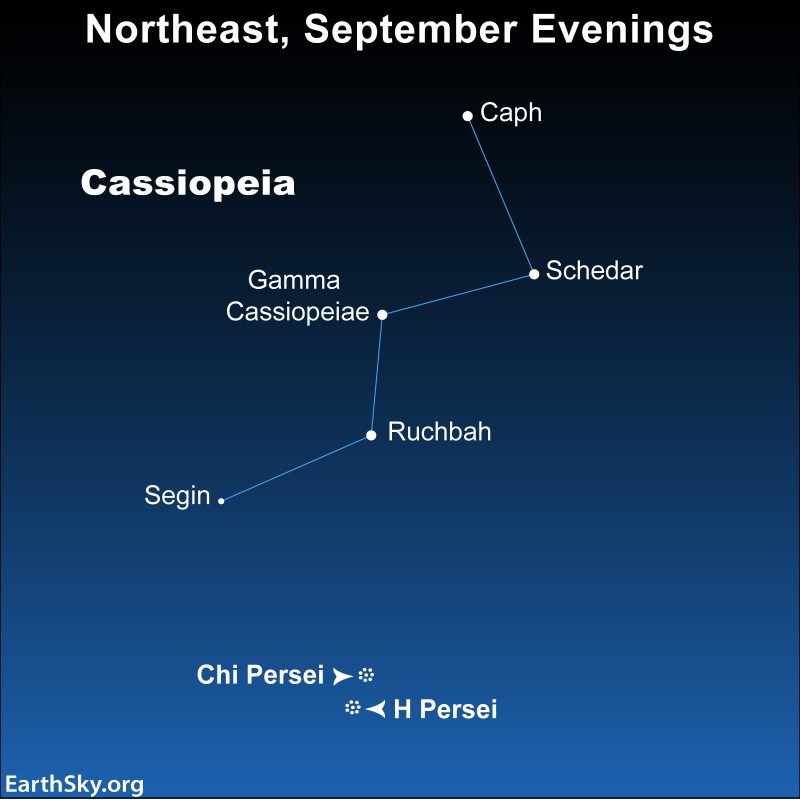

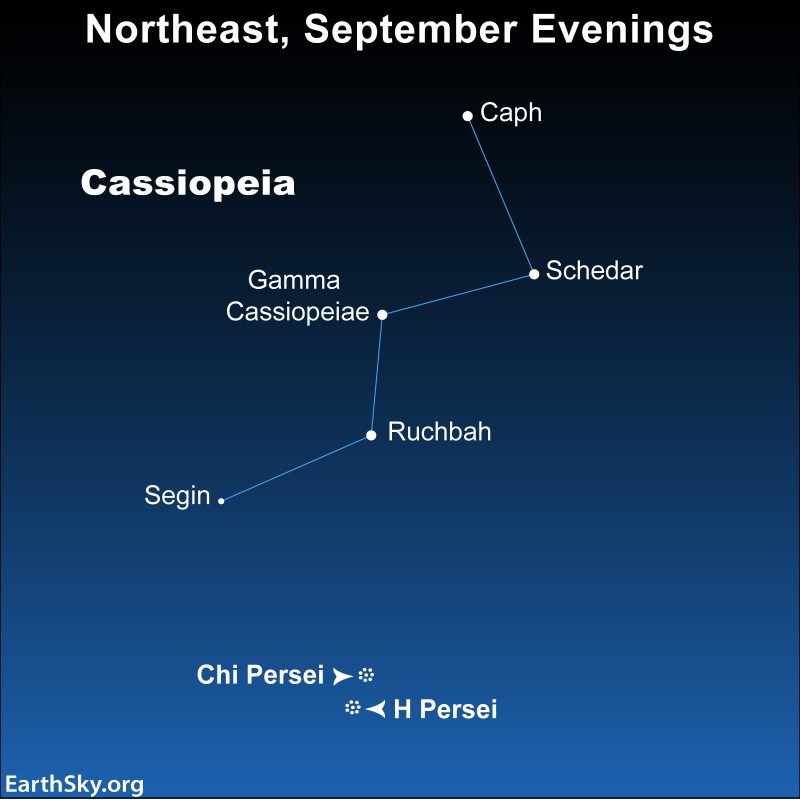

Any late summer evening and throughout northern autumn, Cassiopeia the Queen can be found ascending in the northeast after nightfall. The shape of this constellation makes Cassiopeia’s stars very noticeable. Cassiopeia looks like the letter W (or M).

Look for the Queen starting at nightfall every September. She’ll be higher up in the northeast as autumn unfolds.

For those in the northern U.S. and Canada, Cassiopeia is circumpolar, meaning above the horizon all night long.

How to see Cassiopeia

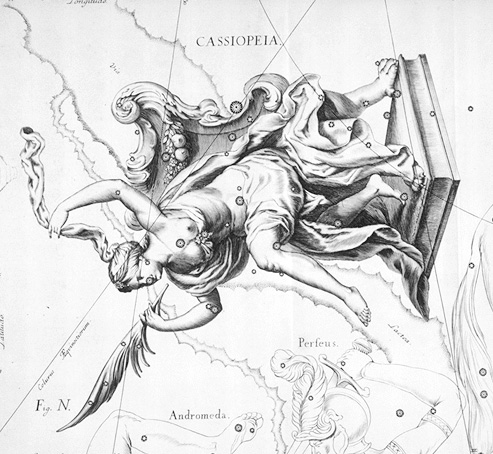

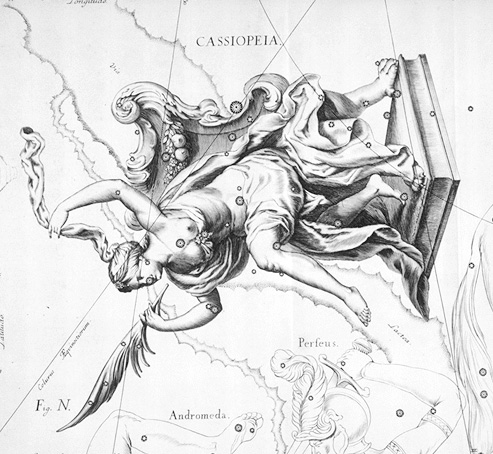

Cassiopeia represents an ancient queen of Ethiopia. You still sometimes hear the old name for this constellation: Cassiopeia’s Chair. And some old star maps depict the queen sitting on the chair, marked by five stars.

These stars – the brightest ones in Cassiopeia – are Schedar, Caph, Gamma Cassiopeiae, Ruchbah and Segin.

Around the middle of the night during the autumn months, Cassiopeia swings above Polaris, the North Star.

Before dawn, look in the northwest.

Opposite the Big Dipper

Cassiopeia is opposite the Big Dipper in the northern sky.

That is, the two constellations lie on opposite sides of the pole star, Polaris.

So when Cassiopeia is high in the sky, as it is on evenings from about September through February, the Big Dipper is low in the sky. Every March, when the Dipper is ascending in the northeast, getting ready to appear prominent again in the evening sky, Cassiopeia can be seen descending in the northwest.

A guide to deep-sky beauties

If you have a dark sky, look below Cassiopeia in the northeast on these autumn evenings for the Double Cluster in Perseus.

These are two open star clusters, each of which consists of young stars still moving together from the primordial cloud of gas and dust that gave birth to the cluster’s stars.

These clusters are familiarly known to stargazers as H and Chi Persei.

Stargazers smile when they peer at them through their binoculars, not only because they are beautiful, but also because of their names. They are named from two different alphabets, the Greek and the Roman. Stars have Greek letter names, but most star clusters don’t. Johann Bayer (1572-1625) gave Chi Persei its Greek letter name.

Then, it’s said, he ran out of Greek letters. That’s when he used a Roman letter – the letter H – to name the other cluster.

Lore of Cassiopeia

In skylore and in Greek mythology, Cassiopeia was a beautiful and vain queen of Ethiopia. It’s said that she committed the sin of pride by boasting that both she and her daughter Andromeda were more beautiful than Nereids, or sea nymphs. Pridefulness, in mythology, is never wise.

Her boast angered Poseidon, god of the sea, who sent a sea monster (Cetus the Whale) to ravage the kingdom. To pacify the monster, Cassiopeia’s daughter, Princess Andromeda, was left tied to a rock by the sea. Cetus was about to devour her when Perseus the Hero happened by on Pegasus, the Flying Horse.

Perseus rescued the princess, and all lived happily … and the gods were pleased, so all of these characters were elevated to the heavens as stars.

But – because of her vanity – Cassiopeia suffered an indignity. At some times of the night or year, this constellation has more the shape of the letter M, and you might imagine the Queen reclining on her starry throne. At other times of year or night – as in the wee hours between midnight and dawn in February and March – Cassiopeia’s Chair dips below the celestial pole. And then this constellation appears to us on Earth more like the letter W.

It’s then that the Lady of the Chair, as she is sometimes called, is said to hang on for dear life. If Cassiopeia the Queen lets go, she will drop from the sky into the ocean below, where the Nereids must still be waiting.

Bottom line: Cassiopeia the Queen is an easy-to-find constellation. It has the shape of a W or M. Look in the north-northeast sky on September and October evenings.

Enjoying EarthSky so far? Sign up for our free daily newsletter today!

The post Cassiopeia ascends in September and October first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/QLm8D9X

Cassiopeia the Queen in autumn

Any late summer evening and throughout northern autumn, Cassiopeia the Queen can be found ascending in the northeast after nightfall. The shape of this constellation makes Cassiopeia’s stars very noticeable. Cassiopeia looks like the letter W (or M).

Look for the Queen starting at nightfall every September. She’ll be higher up in the northeast as autumn unfolds.

For those in the northern U.S. and Canada, Cassiopeia is circumpolar, meaning above the horizon all night long.

How to see Cassiopeia

Cassiopeia represents an ancient queen of Ethiopia. You still sometimes hear the old name for this constellation: Cassiopeia’s Chair. And some old star maps depict the queen sitting on the chair, marked by five stars.

These stars – the brightest ones in Cassiopeia – are Schedar, Caph, Gamma Cassiopeiae, Ruchbah and Segin.

Around the middle of the night during the autumn months, Cassiopeia swings above Polaris, the North Star.

Before dawn, look in the northwest.

Opposite the Big Dipper

Cassiopeia is opposite the Big Dipper in the northern sky.

That is, the two constellations lie on opposite sides of the pole star, Polaris.

So when Cassiopeia is high in the sky, as it is on evenings from about September through February, the Big Dipper is low in the sky. Every March, when the Dipper is ascending in the northeast, getting ready to appear prominent again in the evening sky, Cassiopeia can be seen descending in the northwest.

A guide to deep-sky beauties

If you have a dark sky, look below Cassiopeia in the northeast on these autumn evenings for the Double Cluster in Perseus.

These are two open star clusters, each of which consists of young stars still moving together from the primordial cloud of gas and dust that gave birth to the cluster’s stars.

These clusters are familiarly known to stargazers as H and Chi Persei.

Stargazers smile when they peer at them through their binoculars, not only because they are beautiful, but also because of their names. They are named from two different alphabets, the Greek and the Roman. Stars have Greek letter names, but most star clusters don’t. Johann Bayer (1572-1625) gave Chi Persei its Greek letter name.

Then, it’s said, he ran out of Greek letters. That’s when he used a Roman letter – the letter H – to name the other cluster.

Lore of Cassiopeia

In skylore and in Greek mythology, Cassiopeia was a beautiful and vain queen of Ethiopia. It’s said that she committed the sin of pride by boasting that both she and her daughter Andromeda were more beautiful than Nereids, or sea nymphs. Pridefulness, in mythology, is never wise.

Her boast angered Poseidon, god of the sea, who sent a sea monster (Cetus the Whale) to ravage the kingdom. To pacify the monster, Cassiopeia’s daughter, Princess Andromeda, was left tied to a rock by the sea. Cetus was about to devour her when Perseus the Hero happened by on Pegasus, the Flying Horse.

Perseus rescued the princess, and all lived happily … and the gods were pleased, so all of these characters were elevated to the heavens as stars.

But – because of her vanity – Cassiopeia suffered an indignity. At some times of the night or year, this constellation has more the shape of the letter M, and you might imagine the Queen reclining on her starry throne. At other times of year or night – as in the wee hours between midnight and dawn in February and March – Cassiopeia’s Chair dips below the celestial pole. And then this constellation appears to us on Earth more like the letter W.

It’s then that the Lady of the Chair, as she is sometimes called, is said to hang on for dear life. If Cassiopeia the Queen lets go, she will drop from the sky into the ocean below, where the Nereids must still be waiting.

Bottom line: Cassiopeia the Queen is an easy-to-find constellation. It has the shape of a W or M. Look in the north-northeast sky on September and October evenings.

Enjoying EarthSky so far? Sign up for our free daily newsletter today!

The post Cassiopeia ascends in September and October first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/QLm8D9X

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire