Mercury’s sodium tail

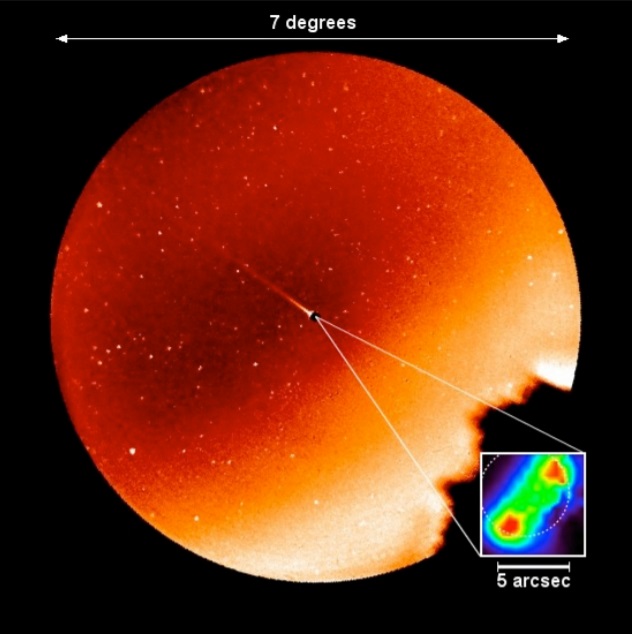

Mercury has a long flowing tail trailing away from the sun, much like a comet, visible in long-exposure photographs. Scientists first predicted Mercury had a tail in the 1980s, then discovered it in 2001. NASA’s Messenger mission also revealed many tail details between 2011 and 2015 when it orbited Mercury. Nowadays, astrophotographers here on Earth are able to capture great shots of Mercury’s tail with the right equipment and a little know-how. Steven Bellavia shares his images and techniques for capturing this unusual phenomenon, below.

Why does Mercury have a tail?

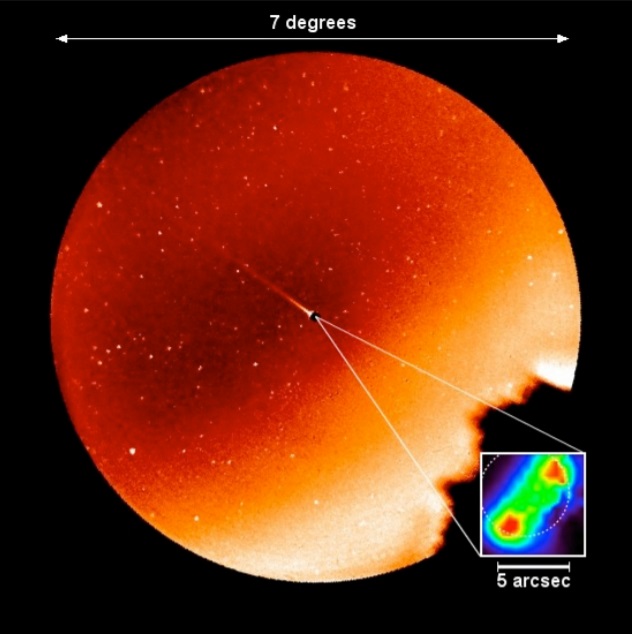

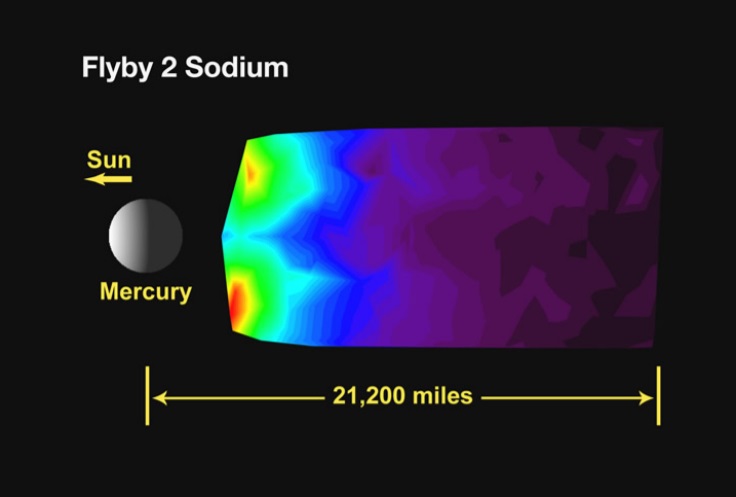

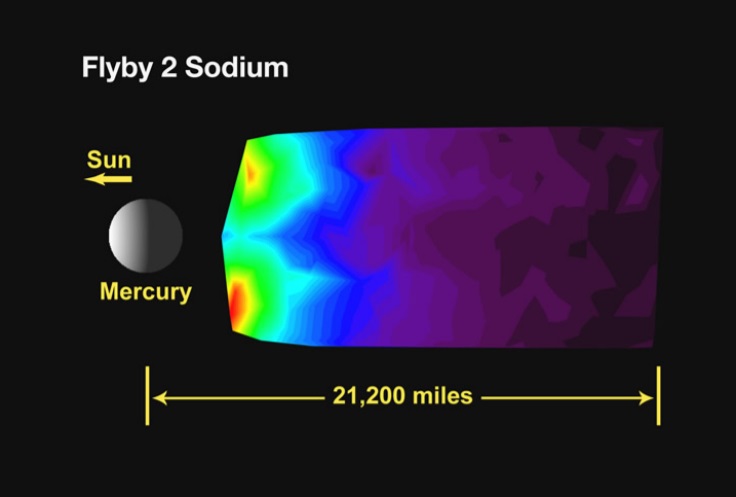

The answer lies in part in sodium atoms. These atoms are freed from Mercury’s surface by the push of sunlight and micrometeorite impacts. The sodium atoms from the surface are blasted into Mercury’s atmosphere and into space, where they form the planet’s tail. Messenger discovered that sunlight scatters off the sodium atoms, giving them a yellow or orange glow. The sun isn’t just selectively blowing sodium off the surface of Mercury, though. Mercury’s tail is made up of many elements, but sodium gets the top billing because it does such a good job of scattering yellow light. This allows the tail to appear on long-exposure photographs.

And how big is Mercury’s sodium tail? It’s roughly 100 times longer than the diameter of Earth!

How to photograph Mercury’s tail

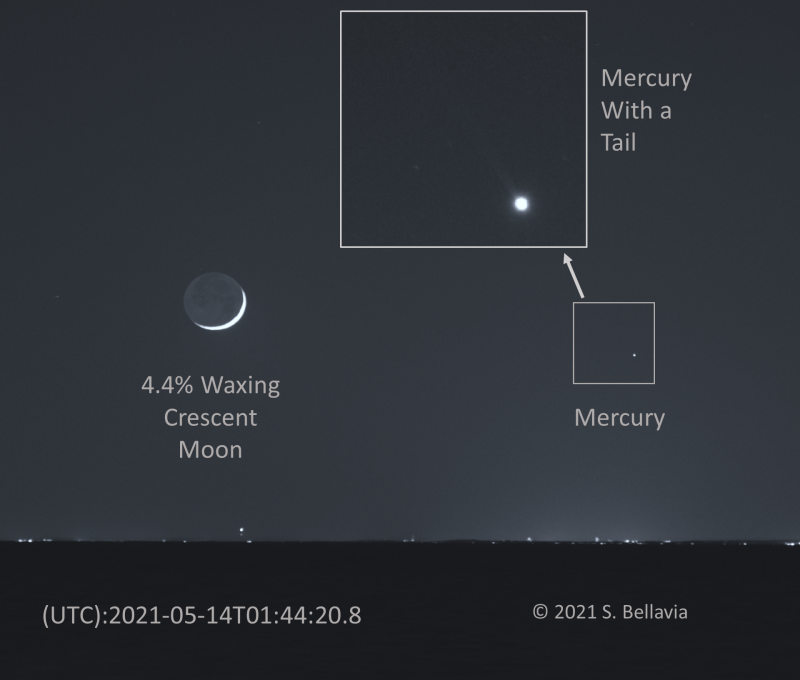

Mercury’s tail is brightest within 16 days of perihelion, the planet’s closest point to the sun. Mercury reaches perihelion every 88 days (it takes 88 days to orbit the sun once). In the photo at top, Steven Bellavia captured Mercury on October 11, 2022, five days past Mercury’s most recent perihelion on October 6, 2022.

Bellavia told EarthSky that an article at Spaceweather.com on May 10, 2021, inspired him to try photographing Mercury’s sodium tail using a 589 nanometer (nm) wavelength filter that lets the sodium light signature through. After reading about it, he was eager to try it for himself. He explained:

On the morning of Wednesday, May 11, 2021, I ordered a 589 nm narrowband filter, with 10 nm of bandpass [the wavelength range of the filter], from Edmund Optics. A friend who owns a 3D printer printed me two rings that I designed to hold the filter, as the filter did not come with standard mounting used in astronomy. I used the new setup within hours of getting it all together.

Ingenious!

Bellavia’s 1st photos of Mercury’s sodium tail

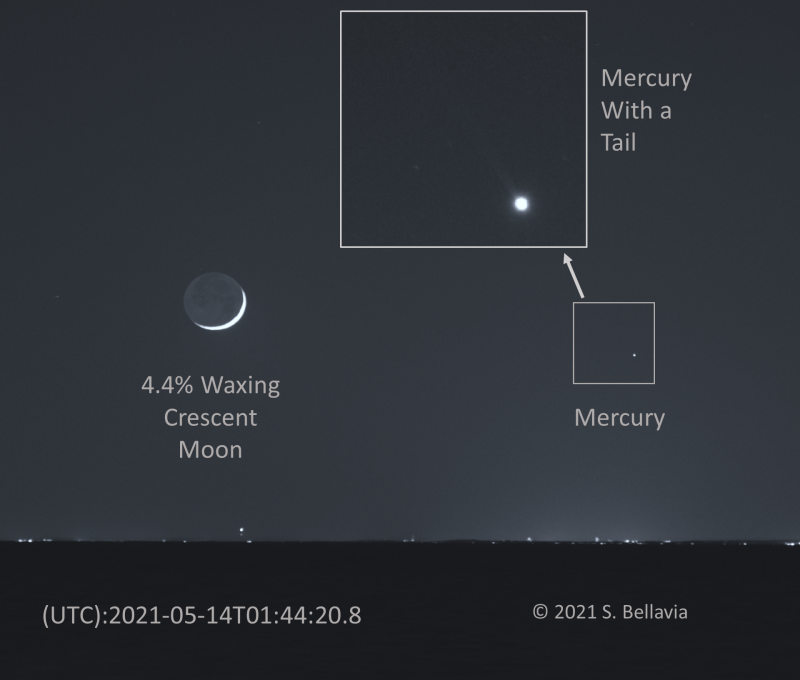

Bellavia first captured photos of Mercury’s tail on both May 13 and 14, 2021. He used a tracking German equatorial mount affixed with a Canon 100mm lens and the filter mounted in front of the lens. On the first night he took 30 exposures of 30 seconds each, while on the second night he took 20 exposures of 60 seconds each using a Borg 90mm refractor. He said:

On the second night, having seen the results from my first attempt, I realized that it would be better to have the telescope and mount track on Mercury itself, as the tail is faint, and all photons collected need to land as frequently as possible on the same pixels in each individual image to reveal it. Also note that on both nights, I would have liked to have taken many more images, but I needed to wait for the background sky to be dark enough to reveal the tail. But Mercury was also setting at this time, either behind land or into clouds near the horizon.

Even with these limitations, Bellavia’s photos of Mercury’s sodium tail are remarkable. Read more about Bellavia’s camera setting here and here at EarthSky Community Photos, and check out his setup and gear for photographing Mercury’s sodium tail at his page on Flickr.

Photos of Mercury’s tail

Sodium in the universe

Astronomers can use filters in the 589 nm range to learn about more objects than just Mercury’s tail. The sun and comets are good targets for sodium filters. Astronomers have also seen sodium streaming from our moon, as well as surrounding Jupiter in a haze after being blown off its moon Io. Discovery of sodium in other star systems allows scientists to learn about rocky exoplanets. They can even use sodium absorption bands to measure redshifts and the size of the universe.

Thank you, Steven Bellavia, for your help in assembling this information.

Have a photo of Mercury’s tail? Submit it to EarthSky Community Photos

Bottom line: Mercury has a long tail flowing away from the sun. Photographers can capture it using filters for the sodium range of the electromagnetic spectrum. See great photos here from Steven Bellavia.

The post See Mercury’s sodium tail in specially filtered photographs first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/TZ928dY

Mercury’s sodium tail

Mercury has a long flowing tail trailing away from the sun, much like a comet, visible in long-exposure photographs. Scientists first predicted Mercury had a tail in the 1980s, then discovered it in 2001. NASA’s Messenger mission also revealed many tail details between 2011 and 2015 when it orbited Mercury. Nowadays, astrophotographers here on Earth are able to capture great shots of Mercury’s tail with the right equipment and a little know-how. Steven Bellavia shares his images and techniques for capturing this unusual phenomenon, below.

Why does Mercury have a tail?

The answer lies in part in sodium atoms. These atoms are freed from Mercury’s surface by the push of sunlight and micrometeorite impacts. The sodium atoms from the surface are blasted into Mercury’s atmosphere and into space, where they form the planet’s tail. Messenger discovered that sunlight scatters off the sodium atoms, giving them a yellow or orange glow. The sun isn’t just selectively blowing sodium off the surface of Mercury, though. Mercury’s tail is made up of many elements, but sodium gets the top billing because it does such a good job of scattering yellow light. This allows the tail to appear on long-exposure photographs.

And how big is Mercury’s sodium tail? It’s roughly 100 times longer than the diameter of Earth!

How to photograph Mercury’s tail

Mercury’s tail is brightest within 16 days of perihelion, the planet’s closest point to the sun. Mercury reaches perihelion every 88 days (it takes 88 days to orbit the sun once). In the photo at top, Steven Bellavia captured Mercury on October 11, 2022, five days past Mercury’s most recent perihelion on October 6, 2022.

Bellavia told EarthSky that an article at Spaceweather.com on May 10, 2021, inspired him to try photographing Mercury’s sodium tail using a 589 nanometer (nm) wavelength filter that lets the sodium light signature through. After reading about it, he was eager to try it for himself. He explained:

On the morning of Wednesday, May 11, 2021, I ordered a 589 nm narrowband filter, with 10 nm of bandpass [the wavelength range of the filter], from Edmund Optics. A friend who owns a 3D printer printed me two rings that I designed to hold the filter, as the filter did not come with standard mounting used in astronomy. I used the new setup within hours of getting it all together.

Ingenious!

Bellavia’s 1st photos of Mercury’s sodium tail

Bellavia first captured photos of Mercury’s tail on both May 13 and 14, 2021. He used a tracking German equatorial mount affixed with a Canon 100mm lens and the filter mounted in front of the lens. On the first night he took 30 exposures of 30 seconds each, while on the second night he took 20 exposures of 60 seconds each using a Borg 90mm refractor. He said:

On the second night, having seen the results from my first attempt, I realized that it would be better to have the telescope and mount track on Mercury itself, as the tail is faint, and all photons collected need to land as frequently as possible on the same pixels in each individual image to reveal it. Also note that on both nights, I would have liked to have taken many more images, but I needed to wait for the background sky to be dark enough to reveal the tail. But Mercury was also setting at this time, either behind land or into clouds near the horizon.

Even with these limitations, Bellavia’s photos of Mercury’s sodium tail are remarkable. Read more about Bellavia’s camera setting here and here at EarthSky Community Photos, and check out his setup and gear for photographing Mercury’s sodium tail at his page on Flickr.

Photos of Mercury’s tail

Sodium in the universe

Astronomers can use filters in the 589 nm range to learn about more objects than just Mercury’s tail. The sun and comets are good targets for sodium filters. Astronomers have also seen sodium streaming from our moon, as well as surrounding Jupiter in a haze after being blown off its moon Io. Discovery of sodium in other star systems allows scientists to learn about rocky exoplanets. They can even use sodium absorption bands to measure redshifts and the size of the universe.

Thank you, Steven Bellavia, for your help in assembling this information.

Have a photo of Mercury’s tail? Submit it to EarthSky Community Photos

Bottom line: Mercury has a long tail flowing away from the sun. Photographers can capture it using filters for the sodium range of the electromagnetic spectrum. See great photos here from Steven Bellavia.

The post See Mercury’s sodium tail in specially filtered photographs first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/TZ928dY

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire