Explorer 1 was a milestone

Explorer 1 was the first U.S. satellite. It was launched just four months after Russia’s Sputnik 1 went up on October 4, 1957. People around the globe heard Sputnik’s unassuming beep beep for 21 days, as this first-ever satellite orbited Earth. And they were riveted. It was over our heads! Such a thing had never been known before. Just a month after the launch of Sputnik 1, Russia launched Sputnik 2. It carried a living animal, a dog named Laika. So the U.S. was determined to launch its own satellite into orbit. And it did, with Explorer 1, on January 31, 1958.

This first U.S. satellite was a critical milestone in the earliest days of the 20th century’s space race. And Explorer 1, the third human-made object in space, also made a momentous discovery. It made the earliest detection of the Van Allen radiation belts that surround Earth. More about the Van Allen Belts below.

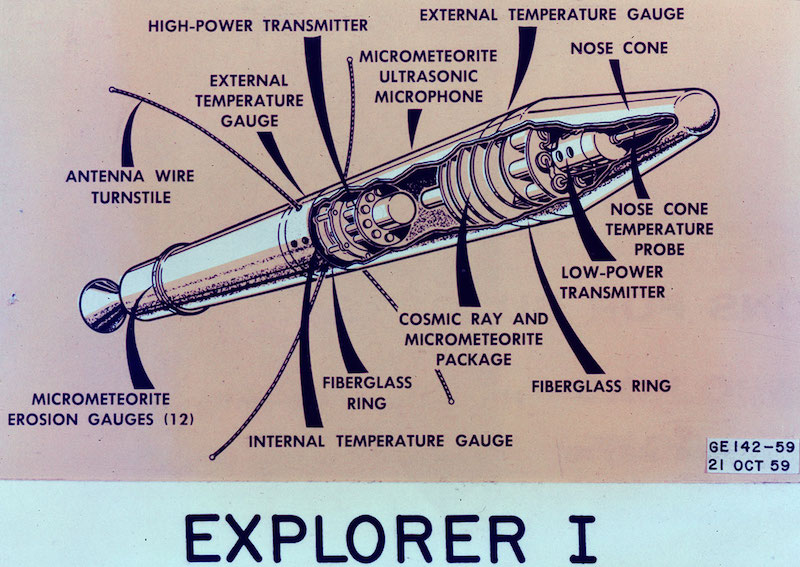

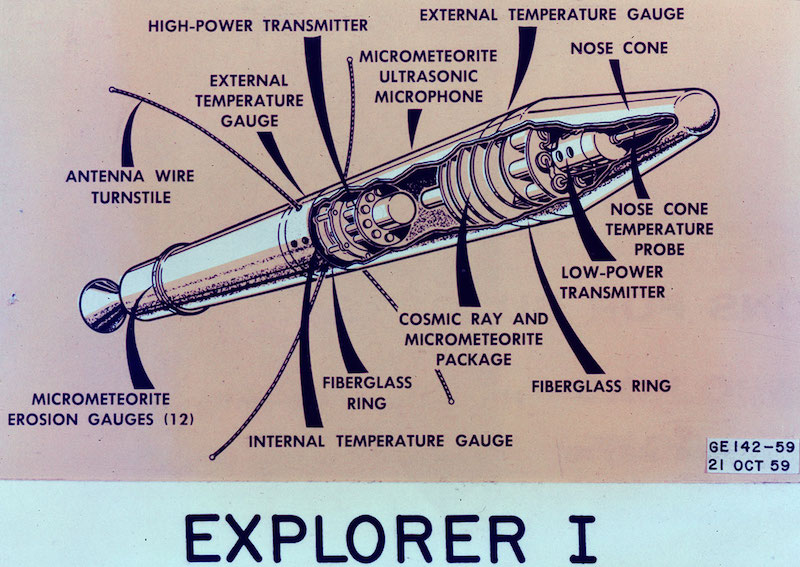

Explorer 1 weighed just 30 pounds (14 kilograms) and was under 7 feet (203 cm) long. It took 114.8 minutes to complete one orbit of Earth – that’s 12.54 orbits a day. Its orbit dipped as low as 220 miles (354 km) and reached a maximum altitude of 1,563 miles (2,515 km). One scientific instrument onboard, a cosmic ray detector, took measurements of radiation as the spacecraft orbited Earth. The data it provided led James Van Allen, the mission’s lead scientist, and his team, to conclude that they had discovered charged particles trapped by Earth’s magnetic field. Data from other satellites eventually confirmed their finding. These zones of trapped charge particles now bear Van Allen’s name.

It helped spur the space race

Explorer 1’s impact was enormous; it helped spur on what was to become an all-out space race.

Russia had launched Sputnik 1, the world’s first artificial satellite, on October 4, 1957. The U.S. quickly launched Explorer 1 in response. William Hayward Pickering led a team at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) that designed and built Explorer 1 in under three months. Pickering was JPL’s director for 22 years until his retirement in 1976.

Explorer 1 flew into space on a Jupiter-C rocket from the U.S Army Ballistic Missile Agency under the guidance of renowned rocket scientist Wernher von Braun. He had worked for the Nazis during World War II but afterward began working for the United States. During the Apollo program, von Braun was the chief architect of the Saturn V, the gargantuan rocket that ultimately sent people to the moon.

There were several science instruments aboard Explorer 1: temperature gauges, micrometeorite sensors and a cosmic-ray detector. The latter made scientific history by detecting the radiation belts that surrounded Earth. These are zones of charged particles – mostly electrons and protons – that Earth’s magnetic field captures from the solar wind.

Explorer 1 and the Van Allen belts

James Van Allen led a team at the University of Iowa that built Explorer 1’s cosmic ray detector. As the rocket ascended, Explorer 1 detected expected count rates from cosmic rays. But in orbit, between periods of expected cosmic ray count rates, the puzzled scientists saw periods of very high counts and zero counts. Adding to the confusion was difficulty in picking up satellite transmissions and tracking the satellite’s orbital path.

Van Allen’s graduate student Carl McIlwain suggested that the zero counts could be due to a very high concentration of charged particles that caused the detector to saturate and therefore record zero counts. McIlwain tested and confirmed this idea in a lab by subjecting a similar detector to an intense source of X-rays. That led the scientists to realize they had discovered a belt of charged particles trapped by the Earth’s magnetic field, a hypothesis that other scientists, Kristian Birkeland and Carl Stoermer, had proposed some time back.

Another satellite, Explorer 3, launched only two months later (after Explorer 2 failed). It was almost identical to Explorer 1 but had a tape recorder that was able to replay the cosmic-ray detector data back to the ground, providing radiation readings over each orbit.

Using this higher-quality data, the scientists confirmed the presence of a radiation belt. They’re now known as the Van Allen radiation belts.

Probing the Van Allen belts

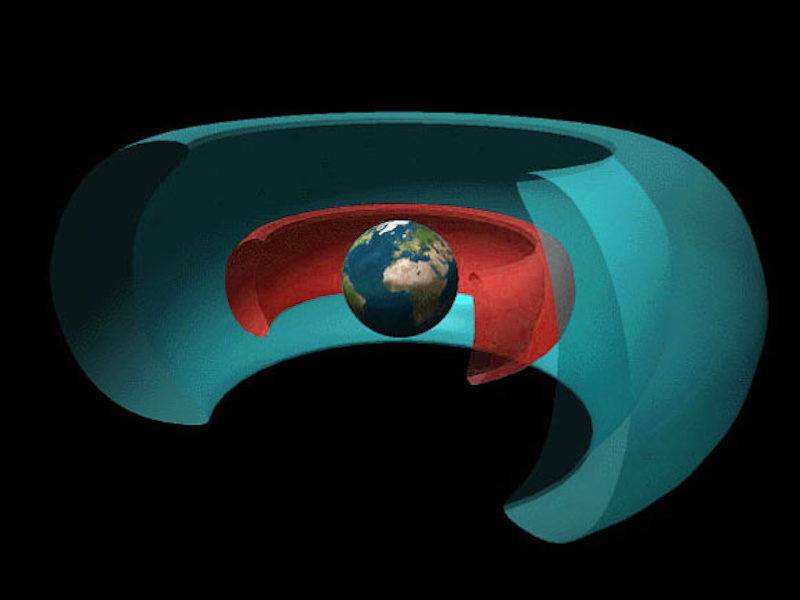

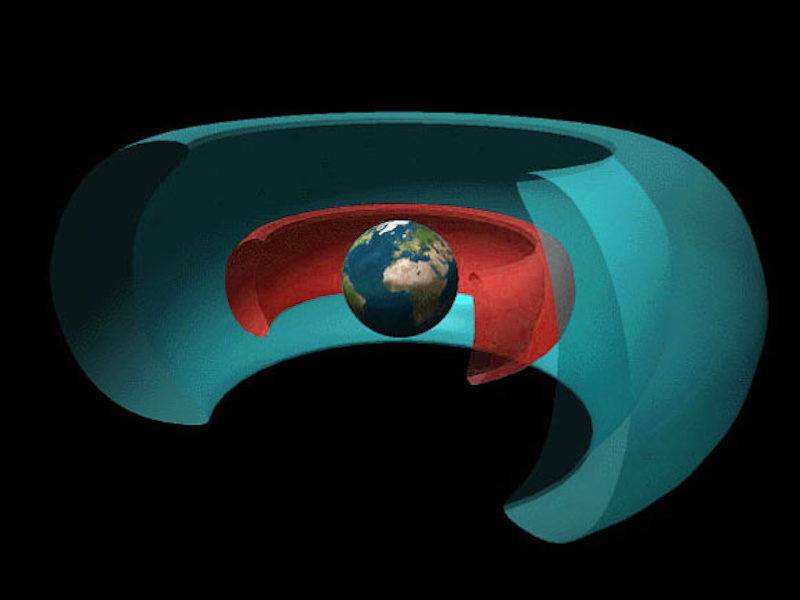

Subsequent space missions have returned data that better characterizes the Van Allen Belts. There are two main belts. The inner Van Allen Belt typically extends from 620 miles (1,000 kilometers) to 7,500 miles (12,000 kilometers) above the Earth but may vary based on solar activity. The outer belt can vary even more in shape and size, usually extending in altitude from 8,100 to 37,300 miles (13,000 to 60,000 km).

In February 2013, NASA announced the discovery of a third radiation belt. This one was a transient phenomenon tied to solar activity. NASA deployed satellites named the Van Allen probes to study the radiation belts, which discovered the new temporary belt.

We now know that radiation belts are quite common. Other planets in our solar system – such as Jupiter, Saturn and Uranus – also have radiation belts similar to Earth’s. Generally speaking, space radiation poses a risk both to astronauts and to spacecraft. But NASA and other space agencies have found ways to cope with the radiation. As this article in Forbes points out:

Charged particles [like those in the Van Allen belts] are damaging to human bodies. But the amount of damage done can range from none to lethal, depending on the energy those particles deposit, the density of those particles, and the length of time you spend being exposed to them.

So how do astronauts survive a passage through the Van Allen belts? They travel through quickly, minimizing their exposure to the radiation.

Explorer 1’s fate

Explorer 1 transmitted data for about four months till its batteries died on May 21, 1958. But it remained in orbit around Earth for 12 years. It circled Earth 58,376 times before burning up upon reentry into the atmosphere on March 31, 1970.

Check out this 1958 documentary about the Explorer 1 satellite (28 minutes).

Bottom line: Explorer 1 was the first satellite launched by the United States. It flew into Earth orbit on a Jupiter-C rocket on January 31, 1958. It gave the U.S. a big boost in the early days of the U.S.-Soviet space race. This pioneering satellite also carried a scientific instrument that detected what we now know as the Van Allen Belts.

The post 1st US satellite – Explorer 1 – launched 64 years ago this week first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/0J6iKg9ve

Explorer 1 was a milestone

Explorer 1 was the first U.S. satellite. It was launched just four months after Russia’s Sputnik 1 went up on October 4, 1957. People around the globe heard Sputnik’s unassuming beep beep for 21 days, as this first-ever satellite orbited Earth. And they were riveted. It was over our heads! Such a thing had never been known before. Just a month after the launch of Sputnik 1, Russia launched Sputnik 2. It carried a living animal, a dog named Laika. So the U.S. was determined to launch its own satellite into orbit. And it did, with Explorer 1, on January 31, 1958.

This first U.S. satellite was a critical milestone in the earliest days of the 20th century’s space race. And Explorer 1, the third human-made object in space, also made a momentous discovery. It made the earliest detection of the Van Allen radiation belts that surround Earth. More about the Van Allen Belts below.

Explorer 1 weighed just 30 pounds (14 kilograms) and was under 7 feet (203 cm) long. It took 114.8 minutes to complete one orbit of Earth – that’s 12.54 orbits a day. Its orbit dipped as low as 220 miles (354 km) and reached a maximum altitude of 1,563 miles (2,515 km). One scientific instrument onboard, a cosmic ray detector, took measurements of radiation as the spacecraft orbited Earth. The data it provided led James Van Allen, the mission’s lead scientist, and his team, to conclude that they had discovered charged particles trapped by Earth’s magnetic field. Data from other satellites eventually confirmed their finding. These zones of trapped charge particles now bear Van Allen’s name.

It helped spur the space race

Explorer 1’s impact was enormous; it helped spur on what was to become an all-out space race.

Russia had launched Sputnik 1, the world’s first artificial satellite, on October 4, 1957. The U.S. quickly launched Explorer 1 in response. William Hayward Pickering led a team at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) that designed and built Explorer 1 in under three months. Pickering was JPL’s director for 22 years until his retirement in 1976.

Explorer 1 flew into space on a Jupiter-C rocket from the U.S Army Ballistic Missile Agency under the guidance of renowned rocket scientist Wernher von Braun. He had worked for the Nazis during World War II but afterward began working for the United States. During the Apollo program, von Braun was the chief architect of the Saturn V, the gargantuan rocket that ultimately sent people to the moon.

There were several science instruments aboard Explorer 1: temperature gauges, micrometeorite sensors and a cosmic-ray detector. The latter made scientific history by detecting the radiation belts that surrounded Earth. These are zones of charged particles – mostly electrons and protons – that Earth’s magnetic field captures from the solar wind.

Explorer 1 and the Van Allen belts

James Van Allen led a team at the University of Iowa that built Explorer 1’s cosmic ray detector. As the rocket ascended, Explorer 1 detected expected count rates from cosmic rays. But in orbit, between periods of expected cosmic ray count rates, the puzzled scientists saw periods of very high counts and zero counts. Adding to the confusion was difficulty in picking up satellite transmissions and tracking the satellite’s orbital path.

Van Allen’s graduate student Carl McIlwain suggested that the zero counts could be due to a very high concentration of charged particles that caused the detector to saturate and therefore record zero counts. McIlwain tested and confirmed this idea in a lab by subjecting a similar detector to an intense source of X-rays. That led the scientists to realize they had discovered a belt of charged particles trapped by the Earth’s magnetic field, a hypothesis that other scientists, Kristian Birkeland and Carl Stoermer, had proposed some time back.

Another satellite, Explorer 3, launched only two months later (after Explorer 2 failed). It was almost identical to Explorer 1 but had a tape recorder that was able to replay the cosmic-ray detector data back to the ground, providing radiation readings over each orbit.

Using this higher-quality data, the scientists confirmed the presence of a radiation belt. They’re now known as the Van Allen radiation belts.

Probing the Van Allen belts

Subsequent space missions have returned data that better characterizes the Van Allen Belts. There are two main belts. The inner Van Allen Belt typically extends from 620 miles (1,000 kilometers) to 7,500 miles (12,000 kilometers) above the Earth but may vary based on solar activity. The outer belt can vary even more in shape and size, usually extending in altitude from 8,100 to 37,300 miles (13,000 to 60,000 km).

In February 2013, NASA announced the discovery of a third radiation belt. This one was a transient phenomenon tied to solar activity. NASA deployed satellites named the Van Allen probes to study the radiation belts, which discovered the new temporary belt.

We now know that radiation belts are quite common. Other planets in our solar system – such as Jupiter, Saturn and Uranus – also have radiation belts similar to Earth’s. Generally speaking, space radiation poses a risk both to astronauts and to spacecraft. But NASA and other space agencies have found ways to cope with the radiation. As this article in Forbes points out:

Charged particles [like those in the Van Allen belts] are damaging to human bodies. But the amount of damage done can range from none to lethal, depending on the energy those particles deposit, the density of those particles, and the length of time you spend being exposed to them.

So how do astronauts survive a passage through the Van Allen belts? They travel through quickly, minimizing their exposure to the radiation.

Explorer 1’s fate

Explorer 1 transmitted data for about four months till its batteries died on May 21, 1958. But it remained in orbit around Earth for 12 years. It circled Earth 58,376 times before burning up upon reentry into the atmosphere on March 31, 1970.

Check out this 1958 documentary about the Explorer 1 satellite (28 minutes).

Bottom line: Explorer 1 was the first satellite launched by the United States. It flew into Earth orbit on a Jupiter-C rocket on January 31, 1958. It gave the U.S. a big boost in the early days of the U.S.-Soviet space race. This pioneering satellite also carried a scientific instrument that detected what we now know as the Van Allen Belts.

The post 1st US satellite – Explorer 1 – launched 64 years ago this week first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/0J6iKg9ve

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire