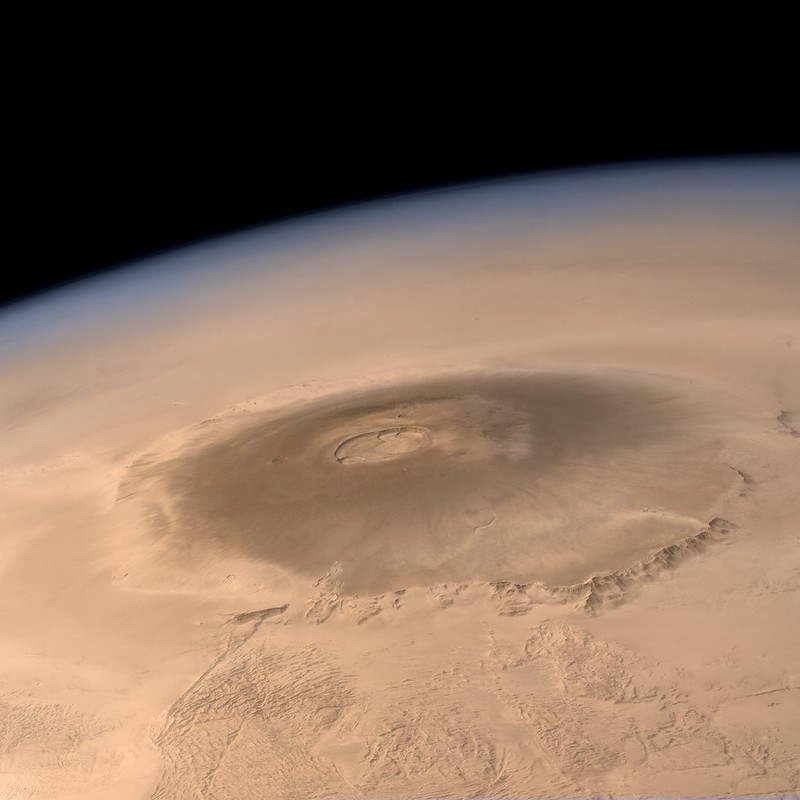

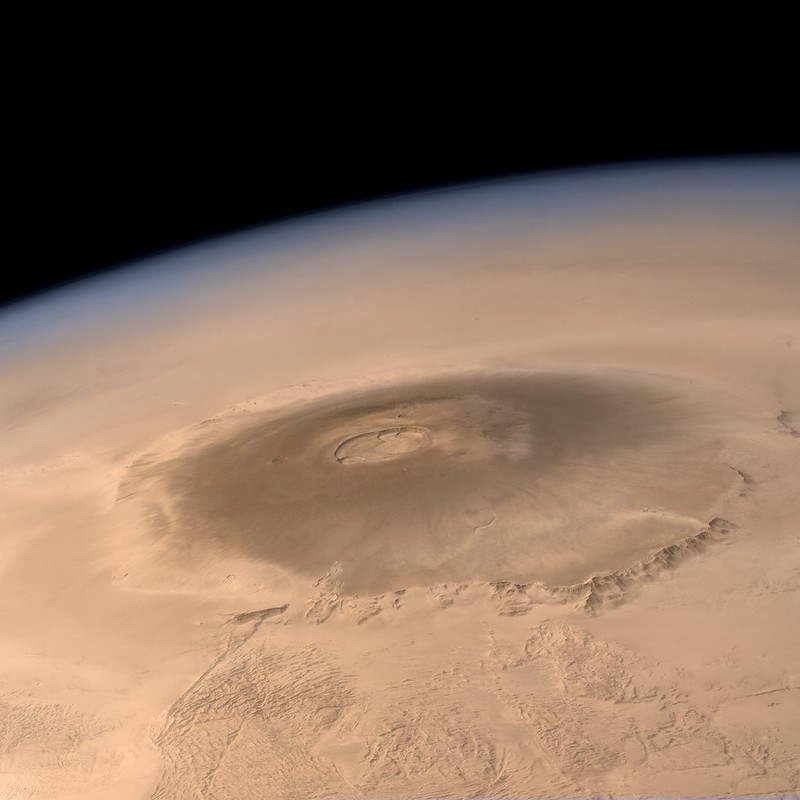

Mars may be home to the largest known volcano in the solar system, Olympus Mons, but today its volcanoes all appear dead or dormant. This calmness belies the shocking violence in Mars’ past. NASA announced on September 15, 2021, that four billion years ago, the little red planet experienced thousands of super eruptions that lasted for 500 million years. These super volcano eruptions buried parts of Mars in ten million cubic kilometers of lava and ash, equivalent to 400 million Olympic-sized swimming pools.

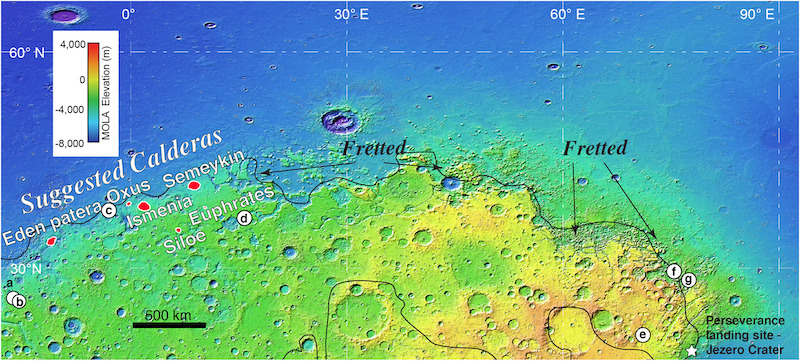

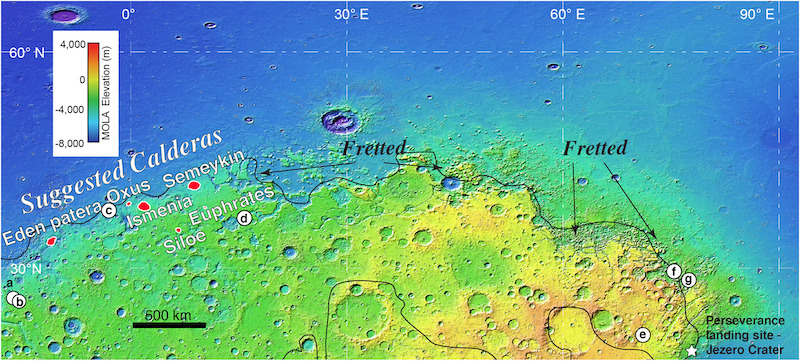

The researchers say that the eruptions occurred in the Arabia Terra region in the northern hemisphere. They published their peer-reviewed findings in Geophysical Research Letters on July 16, 2021.

Martian super volcanoes in Arabia Terra

Over a 500-million-year period, there were thousands of these eruptions in the Arabia Terra region … and they were big. These eruptions were known as super eruptions, the largest and most violent type of volcanic eruption known. They can release so much dust and gas that a planet’s climate becomes altered for decades. The explosive eruptions spewed water vapor, carbon dioxide and sulfur dioxide into the Martian atmosphere.

Patrick Whelley, a geologist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center who led the new research, said:

Each one of these eruptions would have had a significant climate impact, maybe the released gas made the atmosphere thicker or blocked the sun and made the atmosphere colder. Modelers of the Martian climate will have some work to do to try to understand the impact of the volcanoes.

Based on the volume of each caldera, the researchers calculated that thousands of eruptions would have been required to produce the thickness of ash deposits found.

Impact craters were actually calderas

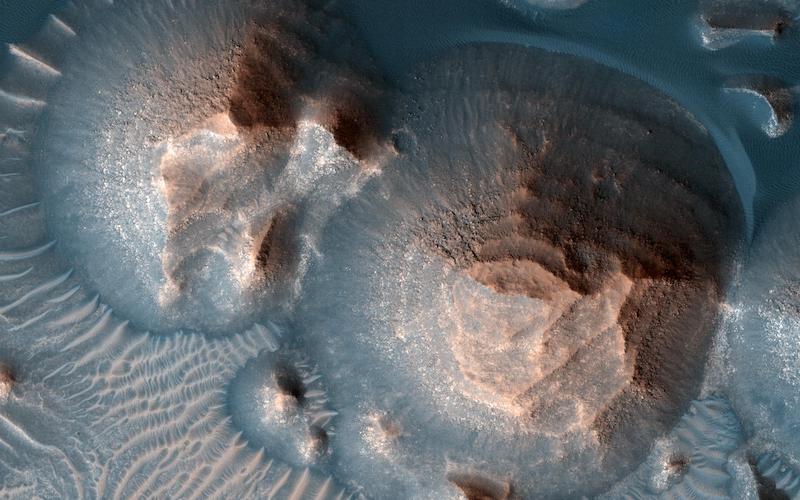

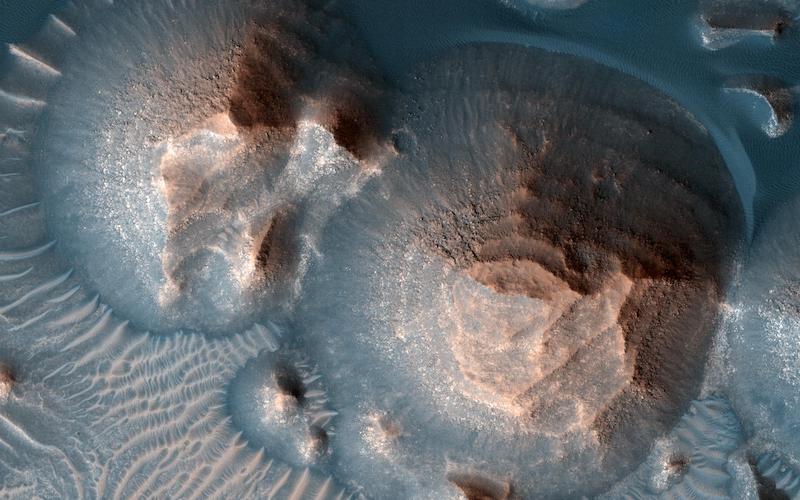

Scientists had previously overlooked the seven volcanoes in Arabia Terra because they mistook the calderas – where the top of a volcano collapses to form a giant hole – for impact craters. Other scientists proposed back in 2013 that they might be volcanic calderas, but there was little follow-up at the time.

These depressions weren’t nicely rounded like most impact craters. Instead, they showed signs of collapse, with deep floors and benches of rock near the outer walls. Whelley and his colleagues read about this and were intrigued. They proposed a different approach; searching for the ash deposits instead of just the volcanoes themselves. Whelley said:

We read that paper and were interested in following up, but instead of looking for volcanoes themselves, we looked for the ash, because you can’t hide that evidence.

As the team of scientists outlined in the paper:

Several large and deep craters in western Arabia Terra, Mars, are thought to be explosive calderas, a type of volcano capable of producing super eruptions. If these craters are calderas, vast layers of volcanic ash should be common in Arabia Terra. While layered deposits have been observed previously in Arabia, until now, no deposits have been associated with the suggested calderas. We present mineral signatures of volcanic ash deposits that thin (from 1 km to 100 m thickness) away from the suggested calderas. Our observations support the idea that explosive calderas do exist in western Arabia Terra, and they produced thousands of super eruptions spread out over 500 million years of ancient Mars history.

Minerals provide clues to volcanic eruptions

So how did the researchers determine that the supposed craters were actually calderas? They studied images from the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) instrument on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO). They found volcanic minerals that water had turned into clay, including montmorillonite, imogolite and allophane. These minerals were located in canyons and craters well away from the calderas, consistent with wind-transported ash deposits.

Another clue came from three-dimensional topographic maps made from other MRO images. When they laid the mineral data over the topographic maps, the researchers found the ash was still well-preserved, instead of jumbled by wind and water as they might expect. The ash layers were still pretty much as pristine as when they first formed. Co-author Jacob Richardson, a geologist at NASA Goddard, said:

That’s when I realized this isn’t a fluke, this is a real signal. We’re actually seeing what was predicted, and that was the most exciting moment for me.

Other scientists previously suggested that the minerals in Arabia Terra had a volcanic origin. This new study now supports that hypothesis. Researchers also suggested that winds would have carried the ash downwind to the east of the volcanoes, which the study also supports. According to co-author Alexandra Matiella Novak:

So we picked it up at that point and said, “OK, well these are minerals that are associated with altered volcanic ash, which has already been documented, so now we’re going to look at how the minerals are distributed to see if they follow the pattern we would expect to see from super eruptions.”

Why only one type of volcano in Arabia Terra?

One lingering mystery is why there seems to have been only one type of volcano, the super volcano, in Arabia Terra. On Earth, various types of volcanoes exist in the same regions in many different places. The researchers say that there may have been similar regions on Earth in the past, but those volcanoes eroded or moved around due to plate tectonics. Mars lacks plate tectonics, so volcanoes tend to remain “anchored” in the same places. That’s also why Olympus Mons is so huge; it just kept growing continuously in one location.

As Richardson noted:

People are going to read our paper and go, “How? How could Mars do that? How can such a tiny planet melt enough rock to power thousands of super eruptions in one location?” I hope these questions bring about a lot of other research.

Is Mars active today?

While these volcanoes, and others, are no longer active on Mars’ surface, there is growing evidence that there may still be residual volcanic activity below ground. There may even be eruptions today, but spaced apart in time by a few million years.

If so, that may potentially provide habitable conditions for microbes below the frigid surface.

Current volcanism, if confirmed, could possibly also help explain the mystery of methane in Mars’ atmosphere.

Bottom line: NASA scientists say that there were once thousands of volcanic eruptions on Mars. These explosive blasts, in the northern Arabia Terra region, were super eruptions, the largest and most powerful kind known. The intense activity began about four billion years ago and continued for about 500 million years.

Source: Stratigraphic Evidence for Early Martian Explosive Volcanism in Arabia Terra

The post Martian super volcanoes lasted millions of years first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/3i67tfI

Mars may be home to the largest known volcano in the solar system, Olympus Mons, but today its volcanoes all appear dead or dormant. This calmness belies the shocking violence in Mars’ past. NASA announced on September 15, 2021, that four billion years ago, the little red planet experienced thousands of super eruptions that lasted for 500 million years. These super volcano eruptions buried parts of Mars in ten million cubic kilometers of lava and ash, equivalent to 400 million Olympic-sized swimming pools.

The researchers say that the eruptions occurred in the Arabia Terra region in the northern hemisphere. They published their peer-reviewed findings in Geophysical Research Letters on July 16, 2021.

Martian super volcanoes in Arabia Terra

Over a 500-million-year period, there were thousands of these eruptions in the Arabia Terra region … and they were big. These eruptions were known as super eruptions, the largest and most violent type of volcanic eruption known. They can release so much dust and gas that a planet’s climate becomes altered for decades. The explosive eruptions spewed water vapor, carbon dioxide and sulfur dioxide into the Martian atmosphere.

Patrick Whelley, a geologist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center who led the new research, said:

Each one of these eruptions would have had a significant climate impact, maybe the released gas made the atmosphere thicker or blocked the sun and made the atmosphere colder. Modelers of the Martian climate will have some work to do to try to understand the impact of the volcanoes.

Based on the volume of each caldera, the researchers calculated that thousands of eruptions would have been required to produce the thickness of ash deposits found.

Impact craters were actually calderas

Scientists had previously overlooked the seven volcanoes in Arabia Terra because they mistook the calderas – where the top of a volcano collapses to form a giant hole – for impact craters. Other scientists proposed back in 2013 that they might be volcanic calderas, but there was little follow-up at the time.

These depressions weren’t nicely rounded like most impact craters. Instead, they showed signs of collapse, with deep floors and benches of rock near the outer walls. Whelley and his colleagues read about this and were intrigued. They proposed a different approach; searching for the ash deposits instead of just the volcanoes themselves. Whelley said:

We read that paper and were interested in following up, but instead of looking for volcanoes themselves, we looked for the ash, because you can’t hide that evidence.

As the team of scientists outlined in the paper:

Several large and deep craters in western Arabia Terra, Mars, are thought to be explosive calderas, a type of volcano capable of producing super eruptions. If these craters are calderas, vast layers of volcanic ash should be common in Arabia Terra. While layered deposits have been observed previously in Arabia, until now, no deposits have been associated with the suggested calderas. We present mineral signatures of volcanic ash deposits that thin (from 1 km to 100 m thickness) away from the suggested calderas. Our observations support the idea that explosive calderas do exist in western Arabia Terra, and they produced thousands of super eruptions spread out over 500 million years of ancient Mars history.

Minerals provide clues to volcanic eruptions

So how did the researchers determine that the supposed craters were actually calderas? They studied images from the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) instrument on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO). They found volcanic minerals that water had turned into clay, including montmorillonite, imogolite and allophane. These minerals were located in canyons and craters well away from the calderas, consistent with wind-transported ash deposits.

Another clue came from three-dimensional topographic maps made from other MRO images. When they laid the mineral data over the topographic maps, the researchers found the ash was still well-preserved, instead of jumbled by wind and water as they might expect. The ash layers were still pretty much as pristine as when they first formed. Co-author Jacob Richardson, a geologist at NASA Goddard, said:

That’s when I realized this isn’t a fluke, this is a real signal. We’re actually seeing what was predicted, and that was the most exciting moment for me.

Other scientists previously suggested that the minerals in Arabia Terra had a volcanic origin. This new study now supports that hypothesis. Researchers also suggested that winds would have carried the ash downwind to the east of the volcanoes, which the study also supports. According to co-author Alexandra Matiella Novak:

So we picked it up at that point and said, “OK, well these are minerals that are associated with altered volcanic ash, which has already been documented, so now we’re going to look at how the minerals are distributed to see if they follow the pattern we would expect to see from super eruptions.”

Why only one type of volcano in Arabia Terra?

One lingering mystery is why there seems to have been only one type of volcano, the super volcano, in Arabia Terra. On Earth, various types of volcanoes exist in the same regions in many different places. The researchers say that there may have been similar regions on Earth in the past, but those volcanoes eroded or moved around due to plate tectonics. Mars lacks plate tectonics, so volcanoes tend to remain “anchored” in the same places. That’s also why Olympus Mons is so huge; it just kept growing continuously in one location.

As Richardson noted:

People are going to read our paper and go, “How? How could Mars do that? How can such a tiny planet melt enough rock to power thousands of super eruptions in one location?” I hope these questions bring about a lot of other research.

Is Mars active today?

While these volcanoes, and others, are no longer active on Mars’ surface, there is growing evidence that there may still be residual volcanic activity below ground. There may even be eruptions today, but spaced apart in time by a few million years.

If so, that may potentially provide habitable conditions for microbes below the frigid surface.

Current volcanism, if confirmed, could possibly also help explain the mystery of methane in Mars’ atmosphere.

Bottom line: NASA scientists say that there were once thousands of volcanic eruptions on Mars. These explosive blasts, in the northern Arabia Terra region, were super eruptions, the largest and most powerful kind known. The intense activity began about four billion years ago and continued for about 500 million years.

Source: Stratigraphic Evidence for Early Martian Explosive Volcanism in Arabia Terra

The post Martian super volcanoes lasted millions of years first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/3i67tfI

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire