The great 1967 solar storm

On May 23, 1967, more than two decades into the high drama of the Cold War, surveillance radars on far-northern parts of the globe (northern Alaska, Greenland, and the U.K.) suddenly and inexplicably jammed. These radars were designed to detect incoming Soviet nuclear missiles. An attack on them by another nation was considered an act of war.

It was a time when tensions between the U.S. and Soviet Union were running high. U.S. military commanders did consider that the jammed radars might be an attack by our enemies. On that fateful day in 1967, these commanders ordered a high alert. They authorized aircraft armed with nuclear weapons to take to the skies. Luckily, before they did, another reason for the jammed radar emerged.

In the end, an unlikely set of heroes – some of the earliest space-weather forecasters – emerged to save the day. They realized that the effects of a powerful solar flare had jammed the radar. Their knowledge of the sun averted what might have become an all-out nuclear war.

Atmospheric physicist Delores Knipp of the University of Colorado and the National Center for Atmospheric Research (both in Boulder, Colorado) collaborated with retired U.S. Air Force officers to bring this story to light in 2016. Their article – how a solar flare nearly triggered a nuclear war – was published on August 9, 2016, in the American Geophysical Union’s journal Space Weather. The authors wrote:

We explain how the May 1967 storm was nearly one with ultimate societal impact, were it not for the nascent efforts of the United States Air Force in expanding its terrestrial weather monitoring-analysis-warning-prediction efforts into the realm of space weather forecasting.

How could this happen?!

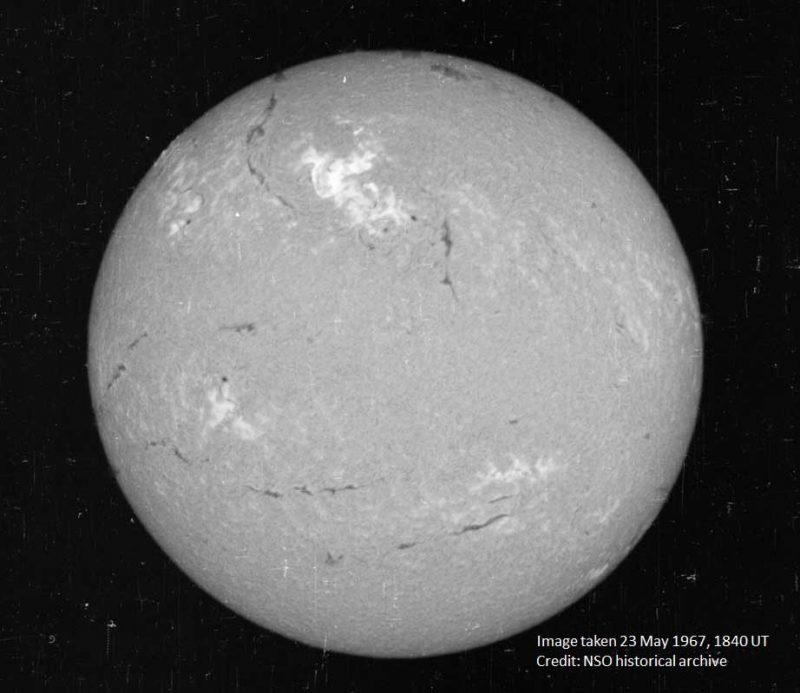

Solar flares are massive bursts of radiation from the sun, associated with sunspots. They’re our solar system’s largest explosive events, lasting from minutes to hours. They’re seen as bright patches on the sun’s surface. But solar flares are ordinary events. Especially near the peak of the sun’s 11-year cycle of activity, they happen often.

So how could people in the 1960s not know about the chance of radar disruption due to a solar flare?

The fact is, they did know. But solar flares weren’t examined widely or regularly until the 1960s. Radio astronomy was a new discipline and prior to that time, studies of the sun and its flares tended to be relatively few and scattered around the globe. Thankfully, by 1967, observatories from around the world were sharing daily updates with solar forecasters at the North American Aerospace Defence Command (NORAD).

And in mid-May that year, a large group of sunspots formed in an area of the sun’s surface. Sunspots are cool, dark patches indicative of atmospheric unrest. Forecasters predicted that a big solar flare was likely to occur. And, indeed, it did. A solar radio observatory in Massachusetts reported unprecedented levels of radio waves due to this activity on the sun. According to Knipp’s 2016 study, observatories in New Mexico and Colorado also reported seeing the flare with their instruments.

As the flare’s effects on Earth unfolded, the three different Ballistic Missile Early Warning System radar sites – the Clear Air Force Station in Alaska, Thule Air Base in Greenland, and Fylingdales in the U.K. – all stopped working. The sudden influx of solar radio waves had overwhelmed their systems, the study authors wrote.

The sun takes blame

Fortunately, scientists quickly recognized the signs that the culprit was somewhere off-Earth. One clue was that all three of the missile sites happened to be in full sunlight. Radar systems rely on detecting radio waves. And, as Earth turned, and the solar radio emissions waned, so did the jamming.

According to the study authors, it was NORAD’s correct diagnosis of the solar storm that prevented the U.S. military from taking disastrous action. Knipp noted in their paper that the critical information was likely relayed to the highest levels of government. It possibly even reached then-President Lyndon B. Johnson.

Solar flares contain tremendous amounts of energy. And after the May 1967 flare died down, its effects were felt on Earth for more than a week. For example, northern lights, and their southern counterparts, aka auroras, are typically seen only at high latitudes, like those near Earth’s poles. During the May 1967 solar storm, they were seen in the sky as far south as New Mexico.

How would a space superstorm affect us today?

The solar storm demonstrated why reliable forecasting of what’s come to be called space weather is so important. The world learned this lesson: intense solar flares are capable of disrupting radio communications.

Today, NASA has a fleet of spacecraft studying the sun at all times. We know that solar flares have the poetnail to disrupt power grids and satellite communication systems.

Knipp and her colleagues wrote in the study:

As a magnetospheric disturbance, the [1967] event ranks near the top in the record books.

The number-one record is maintained by what’s called the Carrington Event of 1859. It’s considered the largest known solar superstorm in recorded history. Telegraph systems failed from the U.S. to Europe. And the northern lights were visible as far south as the Caribbean. However, technology was sparse in 1859. An event of this magnitude would be challenging in our modern world, which is heavily dependent on technological infrastructure.

Bottom line: The U.S. Air Force began preparing for war on May 23, 1967, thinking that the Soviet Union had jammed a set of American surveillance radars. But military space-weather forecasters intervened in time, telling top officials that a powerful sun eruption was to blame. Physicists and Air Force officers described the close call in an August 2016 paper published by the American Geophysical Union.

Source: The May 1967 great storm and radio disruption event

Read more from NASA: Heliophysics missions: Studying the sun and its effects on interplanetary space

The post A 1967 solar storm nearly caused a nuclear war first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/3Cl2h0j

The great 1967 solar storm

On May 23, 1967, more than two decades into the high drama of the Cold War, surveillance radars on far-northern parts of the globe (northern Alaska, Greenland, and the U.K.) suddenly and inexplicably jammed. These radars were designed to detect incoming Soviet nuclear missiles. An attack on them by another nation was considered an act of war.

It was a time when tensions between the U.S. and Soviet Union were running high. U.S. military commanders did consider that the jammed radars might be an attack by our enemies. On that fateful day in 1967, these commanders ordered a high alert. They authorized aircraft armed with nuclear weapons to take to the skies. Luckily, before they did, another reason for the jammed radar emerged.

In the end, an unlikely set of heroes – some of the earliest space-weather forecasters – emerged to save the day. They realized that the effects of a powerful solar flare had jammed the radar. Their knowledge of the sun averted what might have become an all-out nuclear war.

Atmospheric physicist Delores Knipp of the University of Colorado and the National Center for Atmospheric Research (both in Boulder, Colorado) collaborated with retired U.S. Air Force officers to bring this story to light in 2016. Their article – how a solar flare nearly triggered a nuclear war – was published on August 9, 2016, in the American Geophysical Union’s journal Space Weather. The authors wrote:

We explain how the May 1967 storm was nearly one with ultimate societal impact, were it not for the nascent efforts of the United States Air Force in expanding its terrestrial weather monitoring-analysis-warning-prediction efforts into the realm of space weather forecasting.

How could this happen?!

Solar flares are massive bursts of radiation from the sun, associated with sunspots. They’re our solar system’s largest explosive events, lasting from minutes to hours. They’re seen as bright patches on the sun’s surface. But solar flares are ordinary events. Especially near the peak of the sun’s 11-year cycle of activity, they happen often.

So how could people in the 1960s not know about the chance of radar disruption due to a solar flare?

The fact is, they did know. But solar flares weren’t examined widely or regularly until the 1960s. Radio astronomy was a new discipline and prior to that time, studies of the sun and its flares tended to be relatively few and scattered around the globe. Thankfully, by 1967, observatories from around the world were sharing daily updates with solar forecasters at the North American Aerospace Defence Command (NORAD).

And in mid-May that year, a large group of sunspots formed in an area of the sun’s surface. Sunspots are cool, dark patches indicative of atmospheric unrest. Forecasters predicted that a big solar flare was likely to occur. And, indeed, it did. A solar radio observatory in Massachusetts reported unprecedented levels of radio waves due to this activity on the sun. According to Knipp’s 2016 study, observatories in New Mexico and Colorado also reported seeing the flare with their instruments.

As the flare’s effects on Earth unfolded, the three different Ballistic Missile Early Warning System radar sites – the Clear Air Force Station in Alaska, Thule Air Base in Greenland, and Fylingdales in the U.K. – all stopped working. The sudden influx of solar radio waves had overwhelmed their systems, the study authors wrote.

The sun takes blame

Fortunately, scientists quickly recognized the signs that the culprit was somewhere off-Earth. One clue was that all three of the missile sites happened to be in full sunlight. Radar systems rely on detecting radio waves. And, as Earth turned, and the solar radio emissions waned, so did the jamming.

According to the study authors, it was NORAD’s correct diagnosis of the solar storm that prevented the U.S. military from taking disastrous action. Knipp noted in their paper that the critical information was likely relayed to the highest levels of government. It possibly even reached then-President Lyndon B. Johnson.

Solar flares contain tremendous amounts of energy. And after the May 1967 flare died down, its effects were felt on Earth for more than a week. For example, northern lights, and their southern counterparts, aka auroras, are typically seen only at high latitudes, like those near Earth’s poles. During the May 1967 solar storm, they were seen in the sky as far south as New Mexico.

How would a space superstorm affect us today?

The solar storm demonstrated why reliable forecasting of what’s come to be called space weather is so important. The world learned this lesson: intense solar flares are capable of disrupting radio communications.

Today, NASA has a fleet of spacecraft studying the sun at all times. We know that solar flares have the poetnail to disrupt power grids and satellite communication systems.

Knipp and her colleagues wrote in the study:

As a magnetospheric disturbance, the [1967] event ranks near the top in the record books.

The number-one record is maintained by what’s called the Carrington Event of 1859. It’s considered the largest known solar superstorm in recorded history. Telegraph systems failed from the U.S. to Europe. And the northern lights were visible as far south as the Caribbean. However, technology was sparse in 1859. An event of this magnitude would be challenging in our modern world, which is heavily dependent on technological infrastructure.

Bottom line: The U.S. Air Force began preparing for war on May 23, 1967, thinking that the Soviet Union had jammed a set of American surveillance radars. But military space-weather forecasters intervened in time, telling top officials that a powerful sun eruption was to blame. Physicists and Air Force officers described the close call in an August 2016 paper published by the American Geophysical Union.

Source: The May 1967 great storm and radio disruption event

Read more from NASA: Heliophysics missions: Studying the sun and its effects on interplanetary space

The post A 1967 solar storm nearly caused a nuclear war first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/3Cl2h0j

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire