Vega is bright and blue-white

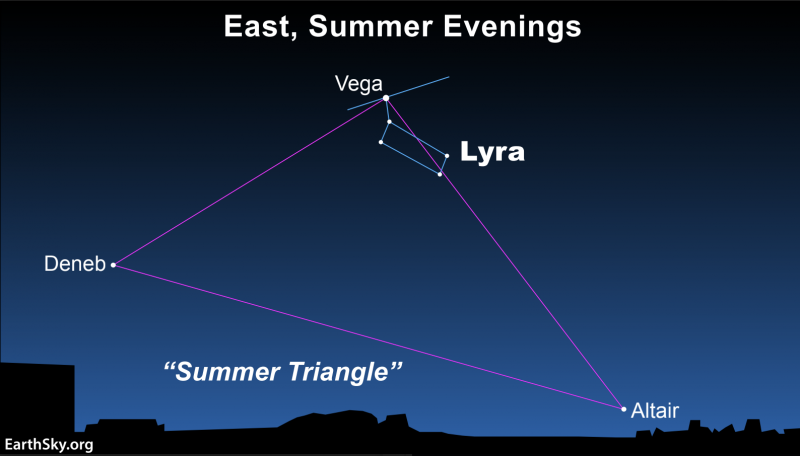

On July evenings, look eastward in the evening for the season’s signature star pattern. It’s an asterism called the Summer Triangle. And, as you might guess, this pattern consists of three stars. They are blue-white Vega, distant Deneb and fast-spinning Altair.

They’re the first three stars to light up the eastern half of the sky after sunset. You can see them even from light-polluted cities, or on a moonlit night.

Watch for the Summer Triangle pattern in the evening beginning around June, through the end of each year.

Blue-white Vega is the brightest of the three stars in the Summer Triangle. It’s the brightest star in the east in the evening on July evenings. And it’s the brightest light in the constellation Lyra the Harp. Thus Vega is also known as Alpha Lyrae.

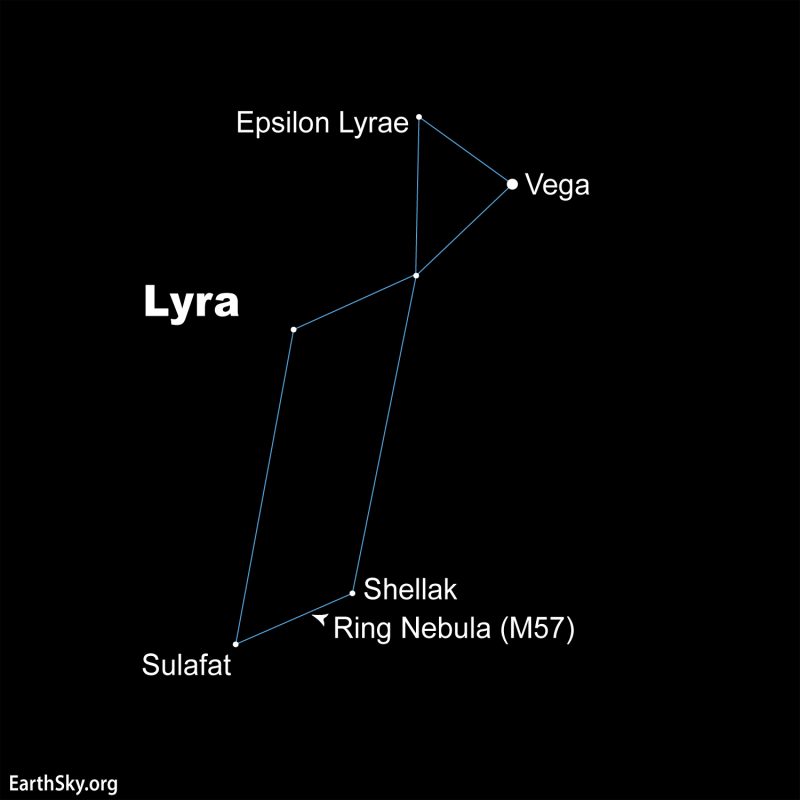

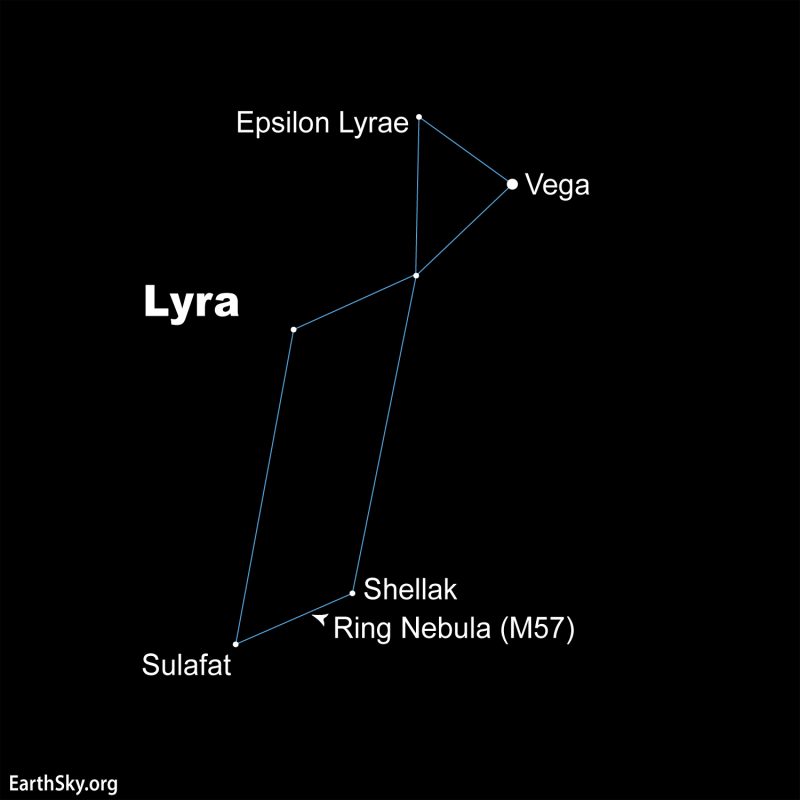

Vega is about 25 light-years away. And many people recognize Vega’s constellation, Lyra. This pattern of stars looks like a triangle of stars connected to a parallelogram.

This beautiful blue-white star – Vega – has a special place in the hearts of skywatchers around the world. Come to know it, and you will see.

How to see Vega and its constellation

Observers in the Northern Hemisphere typically begin noticing Vega in the evening around May, when this star comes into view in the northeast in mid-evening. Throughout northern summer, Vega shines brightly in the east in the evening. It’s high overhead on northern autumn evenings. It’s in the northwest by December evenings.

The little constellation Lyra has some interesting features. Near Vega is Epsilon Lyrae, which telescope users know as a famous double-double star. In other words, through small telescopes, you can see Epsilon Lyrae as double, with each of the two components also a double star.

Meanwhile, between the Gamma and Beta stars in Lyra is another famous telescopic sight, the Ring Nebula, also called M57.

You can see Vega, Epsilon Lyrae and M57 (the Ring Nebula) marked on the chart below.

Vega in history and myth

In western skylore, Vega’s constellation Lyra is said to be a harp played by the legendary Greek musician Orpheus. According to legend, when Orpheus played his harp, neither god nor mortal could turn away.

In western culture, Vega is often called the Harp Star.

But the most beautiful story relating to Vega comes from Asia. There are many variations. In China, the legend speaks of a forbidden romance between the goddess Zhinu – represented by Vega – and a humble farm boy, Niulang – represented by the star Altair. Separated in the night sky by the Milky Way, or Celestial River, the two lovers are allowed to meet only once a year. It’s said that their meeting comes on the 7th night of the 7th moon, when a bridge of magpies forms across the Celestial River, and the two lovers are reunited.

Their reunion marks the time of the Qixi Festival.

In Japan, Vega is called Orihime, a celestial princess or goddess. She falls in love with a mortal, Hikoboshi, represented by the star Altair. But when Orihime’s father finds out, he is enraged and forbids her to see this mere mortal. Then … you know the story. The two lovers are placed in the sky, separated by the Celestial River or Milky Way. Yet the sky gods are kind, and they reunite on the 7th night of the 7th moon each year. Sometimes Hikoboshi’s annual trip across the Celestial River is treacherous, though, and he doesn’t make it. In that case, Orihime’s tears form raindrops that fall over Japan.

Many Japanese celebrations of Tanabata are held in July, but sometimes they are held in August. If it rains, the raindrops are thought to be Orihime’s tears because Hikoboshi could not meet her. Sometimes, the Perseid meteor shower is said to represent Orihime’s tears.

Science of the star Vega

Vega is the 5th-brightest star visible from Earth, and the 3rd-brightest easily visible from mid-northern latitudes, after Sirius and Arcturus. At about 25 light-years in distance, it is the 6th-closest of all the bright stars, or 5th if you exclude Alpha Centauri, which is not easily visible from most of the Northern Hemisphere.

Vega’s distinctly blue color indicates a surface temperature of nearly 17,000 degrees Fahrenheit (9,400 Celsius). So Vega is about 7,000 degrees F (4,000 C) hotter than our sun. This star is roughly 2.5 times the diameter of the sun, and just less than that in mass. But Vega’s internal pressures and temperatures are far greater than our sun’s. And so Vega will burn its internal fuel faster. At only half a billion years old, Vega is already middle-aged. That’s in contrast to our middle-aged sun; the sun is 4-and-a-half billion years old. Vega is only about a 10th our sun’s age. But it will run out of fuel in another half-billion years.

In astronomer-speak, Vega is an “A0V main sequence star.” The “A0” signifies its temperature, whereas the “V” is a measure of energy output (luminosity), indicating that Vega is a normal star (not a giant). “Main sequence” again testifies to the fact that it belongs in the category of normal stars, and that it produces energy through stable fusion of hydrogen into helium. With a visual magnitude (apparent brightness) of 0.03, Vega is only marginally dimmer than Arcturus, but with a distinctly different, cool-blue color.

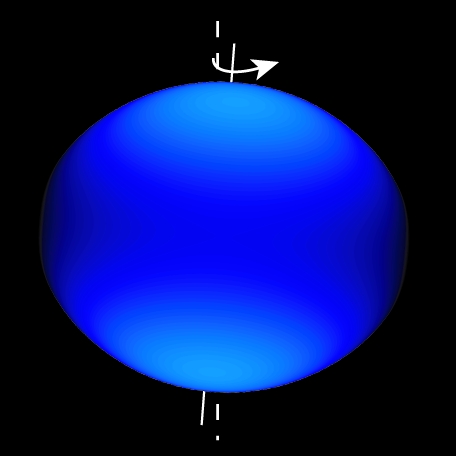

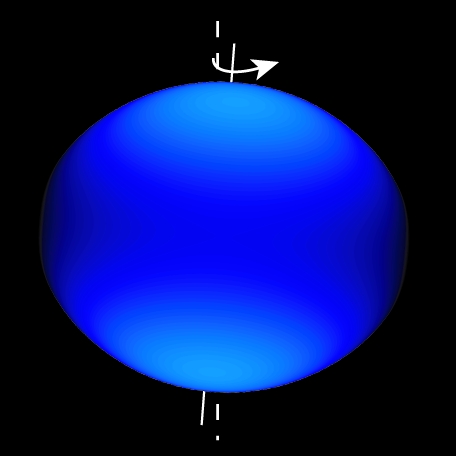

Vega rotates rapidly. It makes a single full rotation about its axis once in about every 12.5 hours. In contrast, our sun requires 27 days to spin once. As a result, if you could visit Vega in space, you’d find it noticeably flattened, as shown in the computer simulation below. Vega is a fast spinner, but’s not the fastest of the three Summer Triangle stars. The star Altair rotates in only about 10 hours!

Vega’s position is RA: 18h 36m 56.3s, dec: +38° 47′ 1.3″.

Bottom line: The star Vega in the constellation Lyra is one of the sky’s most beloved stars, for people around the world.

Our Summer Triangle series includes:

Summer Triangle star: Vega is bright and blue-white

Summer Triangle star: Deneb is distant and very luminous

Summer Triange star: Altair spins fast!

The post Summer Triangle star: Vega is bright and blue-white first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2UZhhzE

Vega is bright and blue-white

On July evenings, look eastward in the evening for the season’s signature star pattern. It’s an asterism called the Summer Triangle. And, as you might guess, this pattern consists of three stars. They are blue-white Vega, distant Deneb and fast-spinning Altair.

They’re the first three stars to light up the eastern half of the sky after sunset. You can see them even from light-polluted cities, or on a moonlit night.

Watch for the Summer Triangle pattern in the evening beginning around June, through the end of each year.

Blue-white Vega is the brightest of the three stars in the Summer Triangle. It’s the brightest star in the east in the evening on July evenings. And it’s the brightest light in the constellation Lyra the Harp. Thus Vega is also known as Alpha Lyrae.

Vega is about 25 light-years away. And many people recognize Vega’s constellation, Lyra. This pattern of stars looks like a triangle of stars connected to a parallelogram.

This beautiful blue-white star – Vega – has a special place in the hearts of skywatchers around the world. Come to know it, and you will see.

How to see Vega and its constellation

Observers in the Northern Hemisphere typically begin noticing Vega in the evening around May, when this star comes into view in the northeast in mid-evening. Throughout northern summer, Vega shines brightly in the east in the evening. It’s high overhead on northern autumn evenings. It’s in the northwest by December evenings.

The little constellation Lyra has some interesting features. Near Vega is Epsilon Lyrae, which telescope users know as a famous double-double star. In other words, through small telescopes, you can see Epsilon Lyrae as double, with each of the two components also a double star.

Meanwhile, between the Gamma and Beta stars in Lyra is another famous telescopic sight, the Ring Nebula, also called M57.

You can see Vega, Epsilon Lyrae and M57 (the Ring Nebula) marked on the chart below.

Vega in history and myth

In western skylore, Vega’s constellation Lyra is said to be a harp played by the legendary Greek musician Orpheus. According to legend, when Orpheus played his harp, neither god nor mortal could turn away.

In western culture, Vega is often called the Harp Star.

But the most beautiful story relating to Vega comes from Asia. There are many variations. In China, the legend speaks of a forbidden romance between the goddess Zhinu – represented by Vega – and a humble farm boy, Niulang – represented by the star Altair. Separated in the night sky by the Milky Way, or Celestial River, the two lovers are allowed to meet only once a year. It’s said that their meeting comes on the 7th night of the 7th moon, when a bridge of magpies forms across the Celestial River, and the two lovers are reunited.

Their reunion marks the time of the Qixi Festival.

In Japan, Vega is called Orihime, a celestial princess or goddess. She falls in love with a mortal, Hikoboshi, represented by the star Altair. But when Orihime’s father finds out, he is enraged and forbids her to see this mere mortal. Then … you know the story. The two lovers are placed in the sky, separated by the Celestial River or Milky Way. Yet the sky gods are kind, and they reunite on the 7th night of the 7th moon each year. Sometimes Hikoboshi’s annual trip across the Celestial River is treacherous, though, and he doesn’t make it. In that case, Orihime’s tears form raindrops that fall over Japan.

Many Japanese celebrations of Tanabata are held in July, but sometimes they are held in August. If it rains, the raindrops are thought to be Orihime’s tears because Hikoboshi could not meet her. Sometimes, the Perseid meteor shower is said to represent Orihime’s tears.

Science of the star Vega

Vega is the 5th-brightest star visible from Earth, and the 3rd-brightest easily visible from mid-northern latitudes, after Sirius and Arcturus. At about 25 light-years in distance, it is the 6th-closest of all the bright stars, or 5th if you exclude Alpha Centauri, which is not easily visible from most of the Northern Hemisphere.

Vega’s distinctly blue color indicates a surface temperature of nearly 17,000 degrees Fahrenheit (9,400 Celsius). So Vega is about 7,000 degrees F (4,000 C) hotter than our sun. This star is roughly 2.5 times the diameter of the sun, and just less than that in mass. But Vega’s internal pressures and temperatures are far greater than our sun’s. And so Vega will burn its internal fuel faster. At only half a billion years old, Vega is already middle-aged. That’s in contrast to our middle-aged sun; the sun is 4-and-a-half billion years old. Vega is only about a 10th our sun’s age. But it will run out of fuel in another half-billion years.

In astronomer-speak, Vega is an “A0V main sequence star.” The “A0” signifies its temperature, whereas the “V” is a measure of energy output (luminosity), indicating that Vega is a normal star (not a giant). “Main sequence” again testifies to the fact that it belongs in the category of normal stars, and that it produces energy through stable fusion of hydrogen into helium. With a visual magnitude (apparent brightness) of 0.03, Vega is only marginally dimmer than Arcturus, but with a distinctly different, cool-blue color.

Vega rotates rapidly. It makes a single full rotation about its axis once in about every 12.5 hours. In contrast, our sun requires 27 days to spin once. As a result, if you could visit Vega in space, you’d find it noticeably flattened, as shown in the computer simulation below. Vega is a fast spinner, but’s not the fastest of the three Summer Triangle stars. The star Altair rotates in only about 10 hours!

Vega’s position is RA: 18h 36m 56.3s, dec: +38° 47′ 1.3″.

Bottom line: The star Vega in the constellation Lyra is one of the sky’s most beloved stars, for people around the world.

Our Summer Triangle series includes:

Summer Triangle star: Vega is bright and blue-white

Summer Triangle star: Deneb is distant and very luminous

Summer Triange star: Altair spins fast!

The post Summer Triangle star: Vega is bright and blue-white first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2UZhhzE

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire