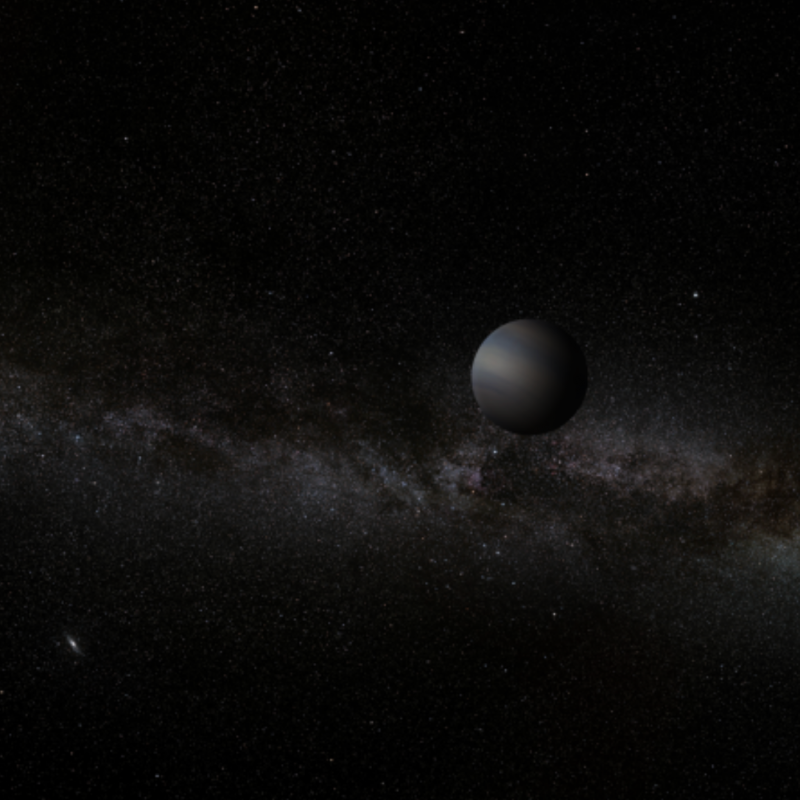

Astronomers said on July 6, 2021, that they’ve used data from the Kepler planet-hunter to find a new crop of rogue planets. They are free-floating planets, unconnected to any star. Like children shoved from a schoolyard by a bigger bully, these rogues might have been ejected from their own star systems by interactions with larger planets. Astronomers used gravitational microlensing to find these lonely planets, amongst a sea of stars, located toward the center of our Milky Way galaxy.

Kepler wasn’t designed for this particular use, but the team teased out the new results anyway.

The peer-reviewed journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society published the new study on July 6.

Rogue planets via gravitational microlensing

What is gravitational microlensing? Albert Einstein first discussed this concept in his 1916 paper on general relativity. He showed that light from a background object, passing another massive body along our line of sight from Earth, would be deflected by the intervening object’s gravity. And he hypothesized that the light of a background object can grow brighter, temporarily, as the intervening body acts as a lens. The light of the background objects might be magnified – brightened – for a few hours or days.

Astronomers regularly use gravitational microlensing to observe distant stars with the help of closer stars. They’ve rarely identified lensing events caused by planets because planets are smaller and less massive than stars. The “lenses” they create in space aren’t as noticeable.

Enter the planet-finding telescope Kepler, which wasn’t initially designed to study the universe via gravitational microlensing. But every 30 minutes for two months, Kepler looked at millions of stars huddled near the center of our home galaxy, the Milky Way. Afterwards, a team of astronomers used new data reduction techniques to look through the information. They found 27 short-lived microlensing signals that could have been caused by small objects, such as rogue planets.

The microlensing signals revealed in Kepler’s data lasted from an hour to 10 days.

Within the 27 signals, the scientists found, four of them (the shortest events) indicate planets that might have masses similar to Earth’s mass.

Like watching for a firefly

Iain McDonald of the University of Manchester in the United Kingdom, now based at the Open University, used Kepler data from 2016 to make these discoveries. He said:

These signals are extremely difficult to find. Our observations pointed an elderly, ailing telescope with blurred vision at one the most densely crowded parts of the sky. There are already thousands of bright stars in that field of view that vary in brightness. Thousands of asteroids skimmed across our field.

From that cacophony, we try to extract tiny, characteristic brightenings caused by planets, and we only have one chance to see a signal before it’s gone.

It’s about as easy as looking for the single blink of a firefly in the middle of a motorway, using only a handheld phone.

Future confirmation

The scientists hope to confirm the existence of these untethered planets with the help of upcoming missions such as NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, scheduled to launch in the mid-2020s. They’re also looking toward ESA’s Euclid mission, which has a launch date in late 2022. Both missions will be able to look for microlensing signals.

Eamonn Kerins of the University of Manchester said:

Kepler has achieved what it was never designed to do, in providing further tentative evidence for the existence of a population of Earth-mass, free-floating planets. Now it passes the baton on to Roman that will be designed to find such signals. These signals are so elusive that Einstein himself thought that they were unlikely ever to be observed.

Bottom line: Scientists using data from the Kepler telescope have discovered a new population of free-floating planets, including four that are similar in size to Earth.

Via the University of Manchester

The post More rogue planets found drifting in Milky Way first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2TFm5K7

Astronomers said on July 6, 2021, that they’ve used data from the Kepler planet-hunter to find a new crop of rogue planets. They are free-floating planets, unconnected to any star. Like children shoved from a schoolyard by a bigger bully, these rogues might have been ejected from their own star systems by interactions with larger planets. Astronomers used gravitational microlensing to find these lonely planets, amongst a sea of stars, located toward the center of our Milky Way galaxy.

Kepler wasn’t designed for this particular use, but the team teased out the new results anyway.

The peer-reviewed journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society published the new study on July 6.

Rogue planets via gravitational microlensing

What is gravitational microlensing? Albert Einstein first discussed this concept in his 1916 paper on general relativity. He showed that light from a background object, passing another massive body along our line of sight from Earth, would be deflected by the intervening object’s gravity. And he hypothesized that the light of a background object can grow brighter, temporarily, as the intervening body acts as a lens. The light of the background objects might be magnified – brightened – for a few hours or days.

Astronomers regularly use gravitational microlensing to observe distant stars with the help of closer stars. They’ve rarely identified lensing events caused by planets because planets are smaller and less massive than stars. The “lenses” they create in space aren’t as noticeable.

Enter the planet-finding telescope Kepler, which wasn’t initially designed to study the universe via gravitational microlensing. But every 30 minutes for two months, Kepler looked at millions of stars huddled near the center of our home galaxy, the Milky Way. Afterwards, a team of astronomers used new data reduction techniques to look through the information. They found 27 short-lived microlensing signals that could have been caused by small objects, such as rogue planets.

The microlensing signals revealed in Kepler’s data lasted from an hour to 10 days.

Within the 27 signals, the scientists found, four of them (the shortest events) indicate planets that might have masses similar to Earth’s mass.

Like watching for a firefly

Iain McDonald of the University of Manchester in the United Kingdom, now based at the Open University, used Kepler data from 2016 to make these discoveries. He said:

These signals are extremely difficult to find. Our observations pointed an elderly, ailing telescope with blurred vision at one the most densely crowded parts of the sky. There are already thousands of bright stars in that field of view that vary in brightness. Thousands of asteroids skimmed across our field.

From that cacophony, we try to extract tiny, characteristic brightenings caused by planets, and we only have one chance to see a signal before it’s gone.

It’s about as easy as looking for the single blink of a firefly in the middle of a motorway, using only a handheld phone.

Future confirmation

The scientists hope to confirm the existence of these untethered planets with the help of upcoming missions such as NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, scheduled to launch in the mid-2020s. They’re also looking toward ESA’s Euclid mission, which has a launch date in late 2022. Both missions will be able to look for microlensing signals.

Eamonn Kerins of the University of Manchester said:

Kepler has achieved what it was never designed to do, in providing further tentative evidence for the existence of a population of Earth-mass, free-floating planets. Now it passes the baton on to Roman that will be designed to find such signals. These signals are so elusive that Einstein himself thought that they were unlikely ever to be observed.

Bottom line: Scientists using data from the Kepler telescope have discovered a new population of free-floating planets, including four that are similar in size to Earth.

Via the University of Manchester

The post More rogue planets found drifting in Milky Way first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2TFm5K7

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire