Mars methane mystery: Curiouser and curiouser

For years now, scientists have been trying to figure out what is creating the methane on Mars. A new study released June 29, 2021, might put them a step closer to solving the Mars methane mystery. On Earth, methane is produced primarily by life. On Mars, methane has been detected by telescopes, orbiters and the Curiosity rover. The evidence seems conclusive. The methane appears to be there, albeit in smaller amounts than on Earth. But there are still nagging inconsistencies. Some instruments detect the gas, while others that should detect it don’t. Why?

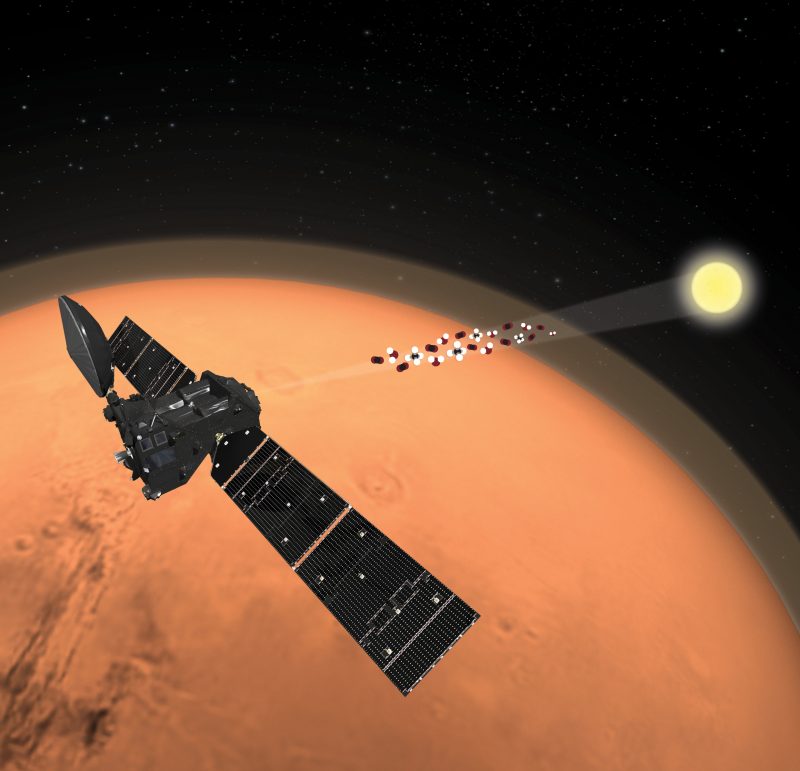

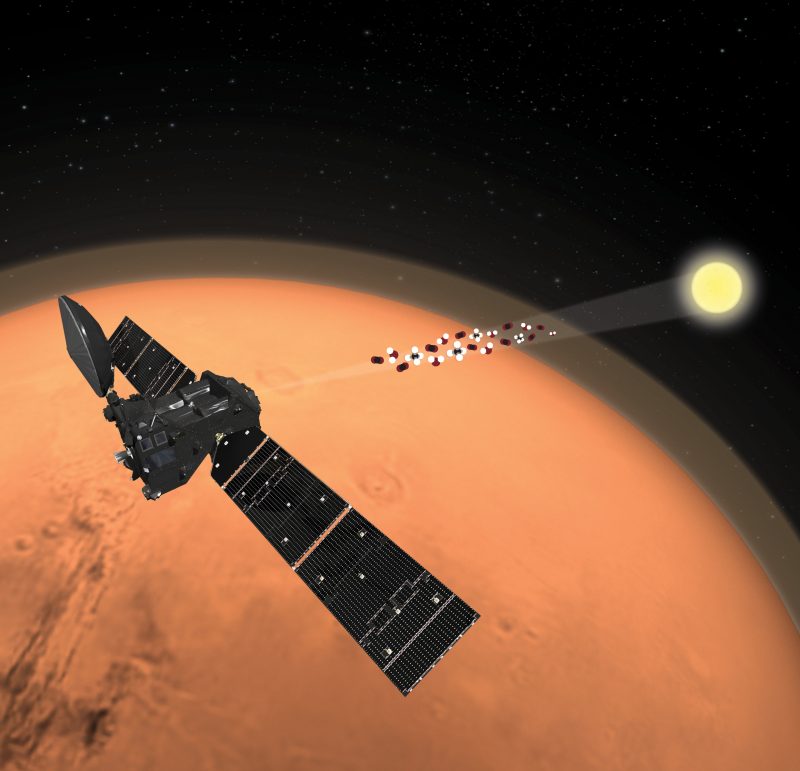

Scientists with the Curiosity rover mission have proposed a solution for the puzzle. The research focuses on the discrepancies between the detection of methane by Curiosity, in Gale Crater, but not by the Trace Gas Orbiter, part of ESA’s ExoMars mission. While Curiosity has made repeated observations of periodic spikes in methane, the Trace Gas Orbiter has yet to detect it definitively.

The new results suggest that it’s the time of day that makes all the difference. Curiosity and the Trace Gas Orbiter are looking for methane at different times of day on Mars.

The journal Astronomy & Astrophysics published the peer-reviewed results on June 29.

Methane on Mars: Yes or no?

The ExoMars mission is really two missions. The first is the Trace Gas Orbiter, launched in 2016. The second consists of a rover and surface platform, and is planned for launch in 2022. Together, they’ll address the question of whether life has ever existed on Mars. In 2016, when the ExoMars mission began, scientists thought it would find Mars methane. Its instruments are extremely sensitive to even trace amounts of the gas.

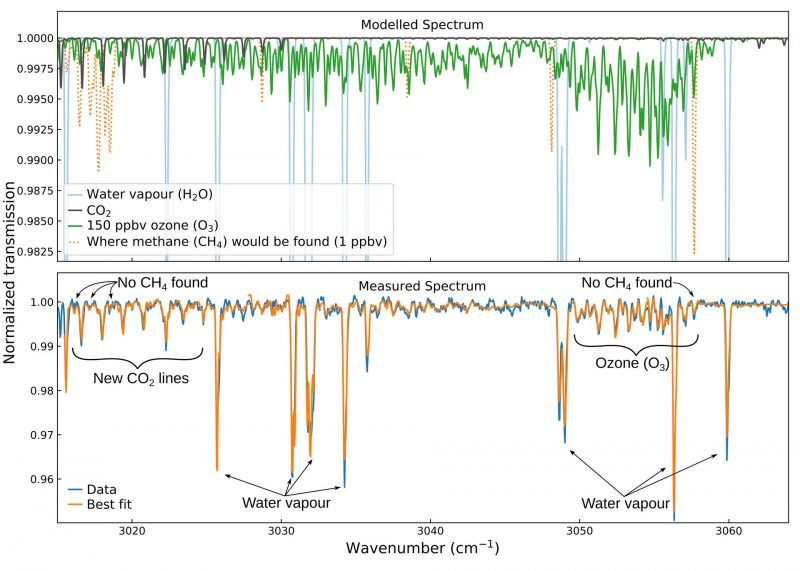

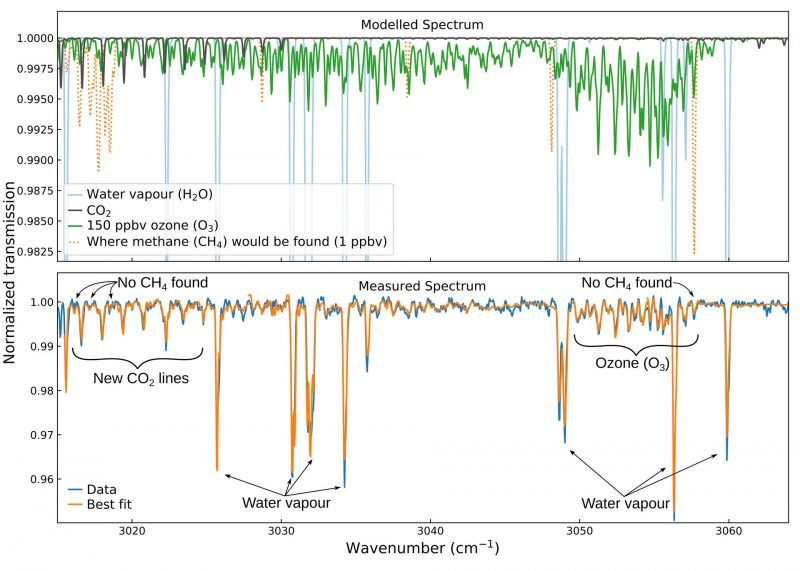

But the Trace Gas Orbiter didn’t detect Mars methane. And that result drove scientists a bit bonkers. It was just so contrary to what Curiosity, and other Mars orbiters and telescopes, had found.

Chris Webster is lead of the Tunable Laser Spectrometer instrument on the Mars Curiosity rover. He commented:

When the Trace Gas Orbiter came on board in 2016, I was fully expecting the orbiter team to report that there’s a small amount of methane everywhere on Mars.

And he said, when Europe’s Trace Gas Orbiter found nothing, no methane at all:

… I was definitely shocked.

Two instruments, two contradictory results

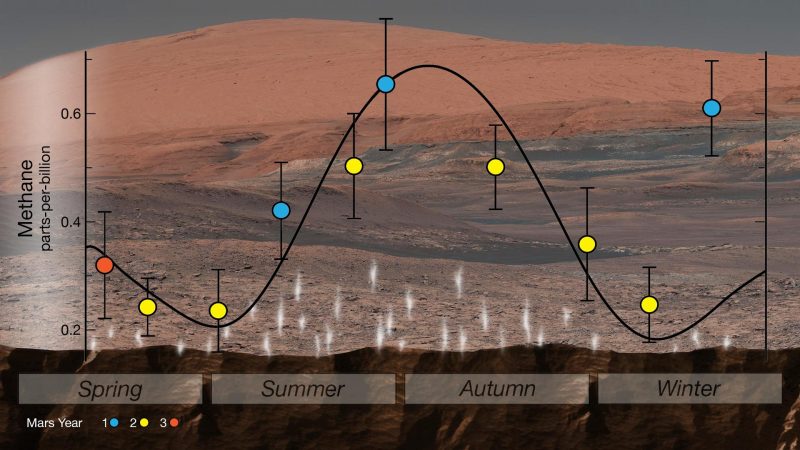

Webster’s instrument aboard Curiosity (the Tunable Laser Spectrometer) was one that helped analyze the methane found at Gale Crater. It found that, on average, there’s less than 1/2 part per billion in volume of background methane at this crater. At times, however, the instrument has detected bursts of methane up to 20 parts per billion (which is significant even if it doesn’t sound like it).

Instruments aboard both the Trace Gas Orbiter and Curiosity should be able to detect exceedingly small amounts of methane. So what the heck? Why such a discrepancy in their results?

Since Curiosity did find methane, could the rover itself have released it? The mission team looked at all possible ways in which the rover could have produced the gas, but found nothing. Webster said:

So we looked at correlations with the pointing of the rover, the ground, the crushing of rocks, the wheel degradation, you name it. I cannot overstate the effort the team has put into looking at every little detail to make sure those measurements are correct, and they are.

With Curiosity’s results seemingly confirmed, another scientist – John E. Moores at York University in Toronto – began looking at the problem. He explained:

I took what some of my colleagues are calling a very Canadian view of this, in the sense that I asked the question: ‘What if Curiosity and the Trace Gas Orbiter are both right?’

A difference of day and night

That’s when Moores suggested the answer might have to do with time of day. Specifically, the Tunable Laser Spectrometer on Curiosity – the instrument that had detected the methane – is used primarily at night. It’s used when no other instruments aboard Curiosity are being used. That’s primarily due to the large amount of power it requires. As Moores reasoned, it would be easier for Curiosity to detect the methane near the surface at night when the air is calmer.

The Trace Gas Orbiter, on the other hand, operates differently. This instrument, in Mars orbit, relies on sunlight to detect methane 3 miles (5 km) above Mars’ surface. So while Curiosity looks for methane at night, the Trace Gas Orbiter looks for it when it’s over Mars’ day side.

And we all know that warmer air rises, and cooler air sinks. During the day on Mars, the thin atmosphere is churned by the sun’s warmth. So any methane that is present at night near the surface – detectable by Curisity – will make its way higher up, into the atmosphere at large, during the Martian day. As it does, it’ll be diluted by the larger atmosphere, to the point that the Trace Gas Orbiter can’t detect it. As Moores explained:

Any atmosphere near a planet’s surface goes through a cycle during the day. So I realized no instrument, especially an orbiting one, would see anything.

Mars methane mystery solved?

Could the answer be as simple as day and night? To check, the Curiosity team collected precise measurements of the atmosphere during the daytime. One nighttime measurement was bracketed by two daytime ones. Its instruments sucked in the air for two hours each time, removing whatever carbon dioxide was present. Since carbon dioxide makes up most (95%) of Mars’ atmosphere, the small amount of remaining air made it easier to detect the methane.

John Moores had predicted that, during the daytime, the amount of methane at Gale Crater – where Curiosity is situated – should go down almost to zero. And indeed it did, according to Paul Mahaffy, who leads the instrument group for the Curiosity rover. He said:

John predicted that methane should effectively go down to zero during the day, and our two daytime measurements confirmed that. So that’s one way of putting to bed this big discrepancy.

Is something destroying the methane?

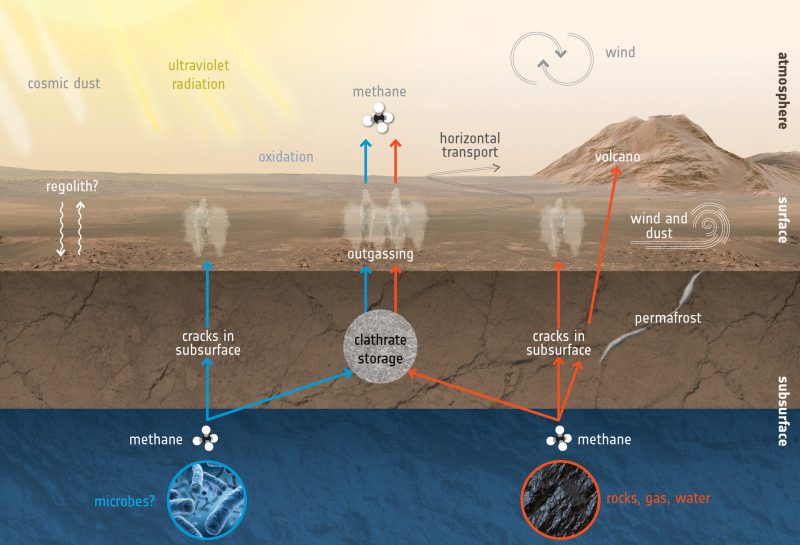

These recent observations might explain why methane was detected at night by Curiosity, but not during the day by the Trace Gas Orbiter. They might … if there weren’t still another mystery that needs explaining. That is, scientists estimate that the methane molecules should be able to last about 300 years in Mars’ atmosphere before being destroyed by solar radiation.

If that’s true, then clearly the methane seeping from Gale Crater and other craters should be detectable by the Trace Gas Orbiter. But the methane seems to disappear. And that means there must be something else destroying it.

But what?

Scientists don’t know. They theorize it might be low-level electric discharges caused by dust (Mars has a lot of dust). Or there might be enough oxygen near Mars’ surface to wipe out the methane before it reaches the upper atmosphere, where the Trace Gas Orbiter could detect it. Webster said:

We need to determine whether there’s a faster destruction mechanism than normal to fully reconcile the data sets from the rover and the orbiter.

And so the search for answers continues.

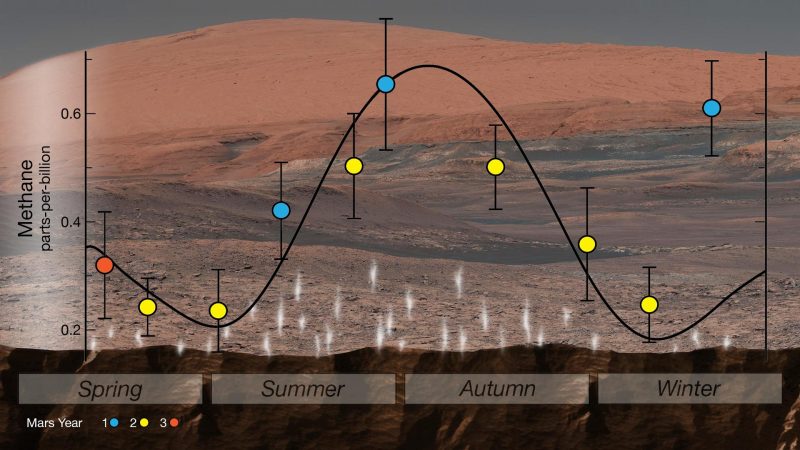

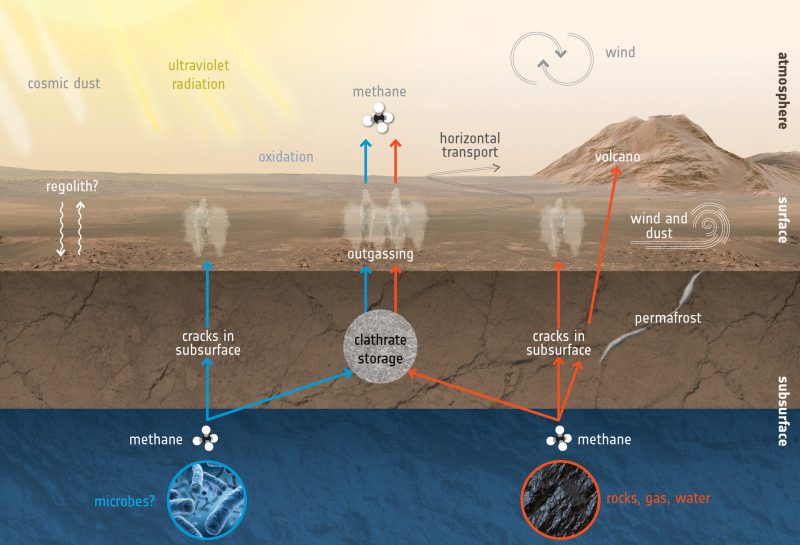

Methane comes from underground

Another study in 2019 also concluded that the amount of methane in Mars’ atmosphere varies on a daily basis, not just seasonally. Wind scouring of rocks was eliminated as a possible source in 2019. Scientists now think the methane originates from underground, but still don’t know if the source is biological, geological or both. It could ancient methane trapped in subsurface ice that periodically gets released to the surface, or it could be currently produced in some other way.

Either explanation could involve biology or geology. The Mars methane mystery still stands!

Bottom line: Scientists think they understand why NASA’s Curiosity rover can detect methane at Mars’ surface, but ESA’s Trace Gas Orbiter can’t detect it from Mars orbit. The difference might be due to the time of day each is looking for methane.

Source: Day-night differences in Mars methane suggest nighttime containment at Gale crater

The post Mars methane mystery? Depends on the time of day first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/3dIvwPT

Mars methane mystery: Curiouser and curiouser

For years now, scientists have been trying to figure out what is creating the methane on Mars. A new study released June 29, 2021, might put them a step closer to solving the Mars methane mystery. On Earth, methane is produced primarily by life. On Mars, methane has been detected by telescopes, orbiters and the Curiosity rover. The evidence seems conclusive. The methane appears to be there, albeit in smaller amounts than on Earth. But there are still nagging inconsistencies. Some instruments detect the gas, while others that should detect it don’t. Why?

Scientists with the Curiosity rover mission have proposed a solution for the puzzle. The research focuses on the discrepancies between the detection of methane by Curiosity, in Gale Crater, but not by the Trace Gas Orbiter, part of ESA’s ExoMars mission. While Curiosity has made repeated observations of periodic spikes in methane, the Trace Gas Orbiter has yet to detect it definitively.

The new results suggest that it’s the time of day that makes all the difference. Curiosity and the Trace Gas Orbiter are looking for methane at different times of day on Mars.

The journal Astronomy & Astrophysics published the peer-reviewed results on June 29.

Methane on Mars: Yes or no?

The ExoMars mission is really two missions. The first is the Trace Gas Orbiter, launched in 2016. The second consists of a rover and surface platform, and is planned for launch in 2022. Together, they’ll address the question of whether life has ever existed on Mars. In 2016, when the ExoMars mission began, scientists thought it would find Mars methane. Its instruments are extremely sensitive to even trace amounts of the gas.

But the Trace Gas Orbiter didn’t detect Mars methane. And that result drove scientists a bit bonkers. It was just so contrary to what Curiosity, and other Mars orbiters and telescopes, had found.

Chris Webster is lead of the Tunable Laser Spectrometer instrument on the Mars Curiosity rover. He commented:

When the Trace Gas Orbiter came on board in 2016, I was fully expecting the orbiter team to report that there’s a small amount of methane everywhere on Mars.

And he said, when Europe’s Trace Gas Orbiter found nothing, no methane at all:

… I was definitely shocked.

Two instruments, two contradictory results

Webster’s instrument aboard Curiosity (the Tunable Laser Spectrometer) was one that helped analyze the methane found at Gale Crater. It found that, on average, there’s less than 1/2 part per billion in volume of background methane at this crater. At times, however, the instrument has detected bursts of methane up to 20 parts per billion (which is significant even if it doesn’t sound like it).

Instruments aboard both the Trace Gas Orbiter and Curiosity should be able to detect exceedingly small amounts of methane. So what the heck? Why such a discrepancy in their results?

Since Curiosity did find methane, could the rover itself have released it? The mission team looked at all possible ways in which the rover could have produced the gas, but found nothing. Webster said:

So we looked at correlations with the pointing of the rover, the ground, the crushing of rocks, the wheel degradation, you name it. I cannot overstate the effort the team has put into looking at every little detail to make sure those measurements are correct, and they are.

With Curiosity’s results seemingly confirmed, another scientist – John E. Moores at York University in Toronto – began looking at the problem. He explained:

I took what some of my colleagues are calling a very Canadian view of this, in the sense that I asked the question: ‘What if Curiosity and the Trace Gas Orbiter are both right?’

A difference of day and night

That’s when Moores suggested the answer might have to do with time of day. Specifically, the Tunable Laser Spectrometer on Curiosity – the instrument that had detected the methane – is used primarily at night. It’s used when no other instruments aboard Curiosity are being used. That’s primarily due to the large amount of power it requires. As Moores reasoned, it would be easier for Curiosity to detect the methane near the surface at night when the air is calmer.

The Trace Gas Orbiter, on the other hand, operates differently. This instrument, in Mars orbit, relies on sunlight to detect methane 3 miles (5 km) above Mars’ surface. So while Curiosity looks for methane at night, the Trace Gas Orbiter looks for it when it’s over Mars’ day side.

And we all know that warmer air rises, and cooler air sinks. During the day on Mars, the thin atmosphere is churned by the sun’s warmth. So any methane that is present at night near the surface – detectable by Curisity – will make its way higher up, into the atmosphere at large, during the Martian day. As it does, it’ll be diluted by the larger atmosphere, to the point that the Trace Gas Orbiter can’t detect it. As Moores explained:

Any atmosphere near a planet’s surface goes through a cycle during the day. So I realized no instrument, especially an orbiting one, would see anything.

Mars methane mystery solved?

Could the answer be as simple as day and night? To check, the Curiosity team collected precise measurements of the atmosphere during the daytime. One nighttime measurement was bracketed by two daytime ones. Its instruments sucked in the air for two hours each time, removing whatever carbon dioxide was present. Since carbon dioxide makes up most (95%) of Mars’ atmosphere, the small amount of remaining air made it easier to detect the methane.

John Moores had predicted that, during the daytime, the amount of methane at Gale Crater – where Curiosity is situated – should go down almost to zero. And indeed it did, according to Paul Mahaffy, who leads the instrument group for the Curiosity rover. He said:

John predicted that methane should effectively go down to zero during the day, and our two daytime measurements confirmed that. So that’s one way of putting to bed this big discrepancy.

Is something destroying the methane?

These recent observations might explain why methane was detected at night by Curiosity, but not during the day by the Trace Gas Orbiter. They might … if there weren’t still another mystery that needs explaining. That is, scientists estimate that the methane molecules should be able to last about 300 years in Mars’ atmosphere before being destroyed by solar radiation.

If that’s true, then clearly the methane seeping from Gale Crater and other craters should be detectable by the Trace Gas Orbiter. But the methane seems to disappear. And that means there must be something else destroying it.

But what?

Scientists don’t know. They theorize it might be low-level electric discharges caused by dust (Mars has a lot of dust). Or there might be enough oxygen near Mars’ surface to wipe out the methane before it reaches the upper atmosphere, where the Trace Gas Orbiter could detect it. Webster said:

We need to determine whether there’s a faster destruction mechanism than normal to fully reconcile the data sets from the rover and the orbiter.

And so the search for answers continues.

Methane comes from underground

Another study in 2019 also concluded that the amount of methane in Mars’ atmosphere varies on a daily basis, not just seasonally. Wind scouring of rocks was eliminated as a possible source in 2019. Scientists now think the methane originates from underground, but still don’t know if the source is biological, geological or both. It could ancient methane trapped in subsurface ice that periodically gets released to the surface, or it could be currently produced in some other way.

Either explanation could involve biology or geology. The Mars methane mystery still stands!

Bottom line: Scientists think they understand why NASA’s Curiosity rover can detect methane at Mars’ surface, but ESA’s Trace Gas Orbiter can’t detect it from Mars orbit. The difference might be due to the time of day each is looking for methane.

Source: Day-night differences in Mars methane suggest nighttime containment at Gale crater

The post Mars methane mystery? Depends on the time of day first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/3dIvwPT

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire