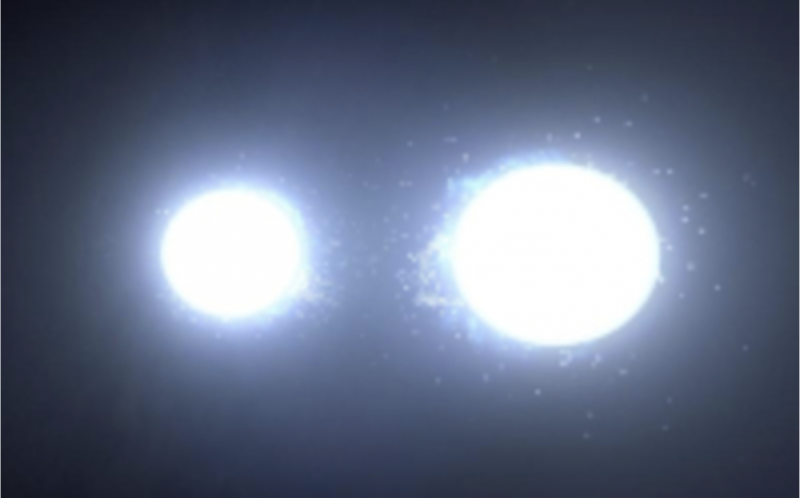

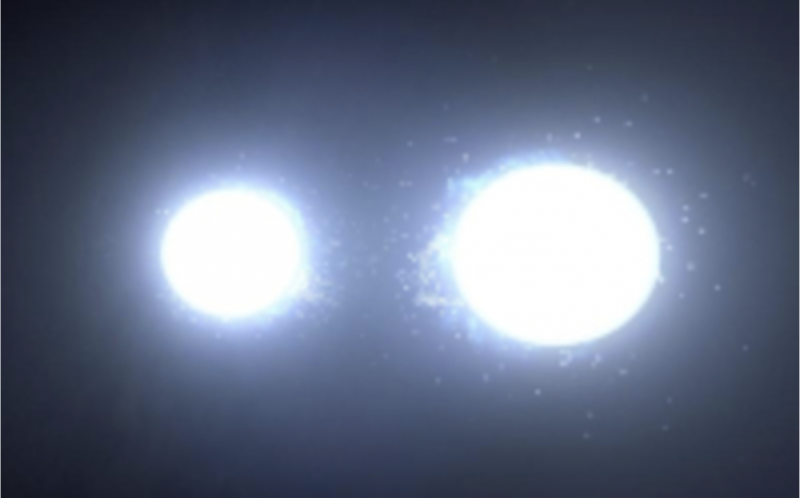

Artist’s concept of the 2 large, hot stars in the Spica system via UA Little Rock.

From a distance of 262 light-years away, Spica appears to us on Earth to be a lone bluish-white star in a quiet region of the sky. But Spica consists of two stars and maybe more. The pair are both larger and hotter than our sun, and they’re separated by only 11 million miles (less than 18 million km), orbiting their common center of gravity in only four days. In contrast, Earth is 93.3 million miles (150 million km, or 1 astronomical unit, aka AU) from our sun, while the two stars in Spica are only .12 AU from each other.

The two stars in the Spica system are individually indistinguishable from a single point of light, even with a telescope. The dual nature of this star was revealed only by analysis of its light with a spectroscope, an instrument that splits light into its component colors.

The star Spica is also called Alpha Virginis, because it’s the brightest star in the constellation Virgo the Maiden. Our eyes see it as distinctly blue-white. Photo by Fred Espenak at AstroPixels.

The two stars are so close, and they orbit so quickly around each other, that their mutual gravity distorts each star into an egg shape. It’s thought that the pointed ends of these egg-shaped stars face each other as they whirl around. Slight magnitude variations may be evidence for such a distortion. The magnitude changes could be the result of the stars showing more or less surface area as they move through different orientations in their orbits.

The pair of stars are both dwarfs brightening near the end of their lifetimes, making them so hot that Spica is considered one of the hottest first magnitude stars. The hottest of the pair is 22,400 Kelvin – blistering compared to the sun’s 5,800 Kelvin – and it may someday explode in a supernova.

The light from Spica’s two stars, taken together, is on average more than 2,200 times brighter than our sun’s light. Their diameters are estimated to be 7.8 and 4 times the sun’s diameter.

Spica is one of several bright stars that the moon can occult (eclipse). Based on observations of how the star’s light is extinguished when the moon passes in front, some astronomers think that it may not just be a spectroscopic binary star. Instead, they feel that there may be as many as three other stars in the system. This would make Spica not a single or even a double, but a quintuple star!

Artist’s concept of Spica from a hypothetical planet. Image via Glyphweb.com

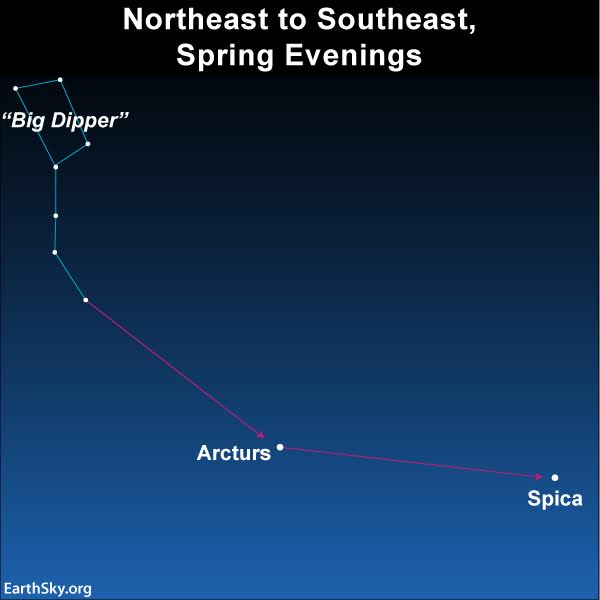

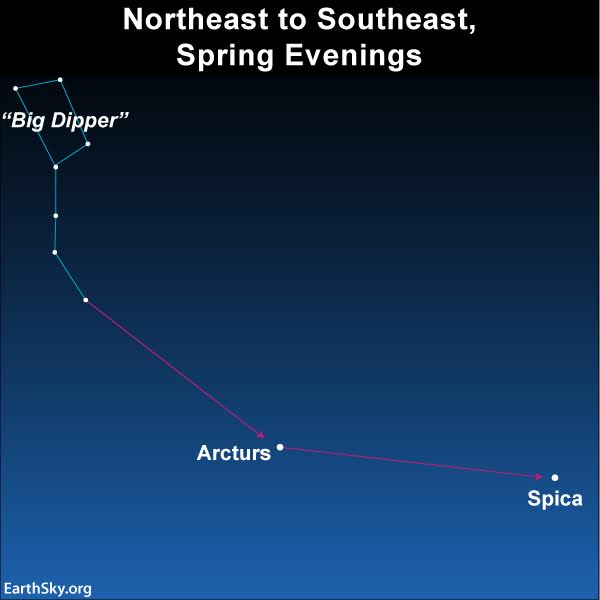

How to find Spica. The best evening views of Spica come from spring to late summer when this star arcs across the southern sky. In the month of May, as seen from the Northern Hemisphere, you’ll find Spica in the southeast in early evening. From the Southern Hemisphere, Spica is closer to due east. From all of Earth in May, as night passes, Spica appears to move westward. Spica rises earlier each evening so that – by the end of August – Spica can be viewed only briefly in the west to west-southwest sky as darkness falls.

Look for the Big Dipper in the northern sky. The Dipper is highest in the sky in northern spring and summer. Notice that the Big Dipper has a bowl and a long, curved handle. Find the Dipper, and then follow the curve of its handle outward, away from the Dipper itself. The first bright star you come to is orange Arcturus, but if you continue past it in the curving path, the next bright star is Spica. Scouts and stargazers remember this trick with the saying: Follow the arc to Arcturus, and speed on (or drive a spike) to Spica.

Spica shines at magnitude 1.04, making it the brightest light in the constellation Virgo the Maiden. Spica is the 15th brightest star visible from anywhere on Earth. It’s virtually the same brightness as Antares in the constellation Scorpius, so sometimes Antares is listed as the 15th and Spica as the 16th brightest. No matter. Identify this beautiful blue-white star with the Big Dipper’s help to spot it in the sky. If you do, this star will be your friend for life.

Use the Big Dipper to “follow the arc to Arcturus” and “drive a spike to Spica.” Read more.

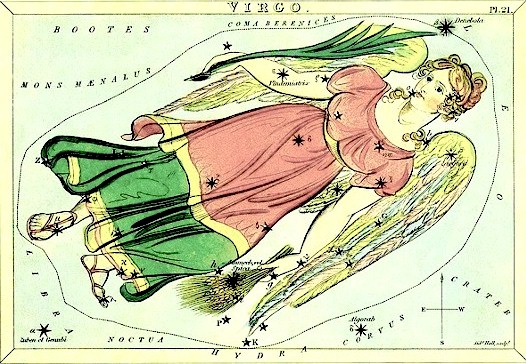

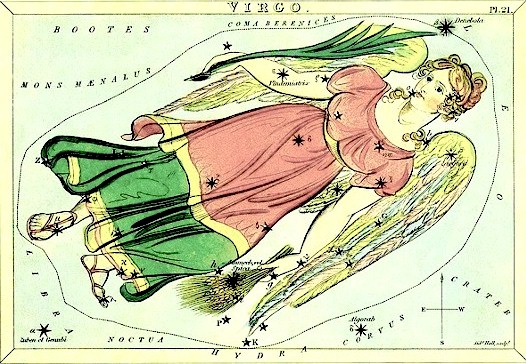

History and mythology of Spica. Spica is from the Latin word for “ear,” and the general connotation is that it refers to an “ear of wheat.” Indeed, the star and the constellation Virgo itself were sometimes associated with the Greek goddess of the harvest, Ceres.

Classical illustration of the constellation Virgo the Maiden, via constellationsofwords.com.

There are many names and stories for Spica’s constellation – Virgo – in mythology, and by association with Spica as well. Fewer stories refer to Spica independently. Many classical references refer to Virgo’s stars as a goddess or with some association with wheat or the harvest, due to the fact that the sun passes through Virgo in the fall. In Greece and Rome she typically was Astraea, the very personification of Justice; or Persephone, daughter of Ceres. In Egypt, Virgo was identified with Isis, and Spica was considered her lute bearer. In ancient China, Spica was a special star of spring known as the Horn.

One Arabic name was Azimech, derived from words meaning Defenseless One or Solitary One. This title may be in reference to Spica’s solitary status with no other bright stars nearby. But Spica is not the most solitary star. That honor goes to Fomalhaut, sometimes called the Autumn Star.

Spica’s position is RA: 13h 25m 12s, dec: -11° 09′ 41″

Bottom line: Spica is the brightest star in Virgo. Spica is at least two stars orbiting extremely close together, distorting each other into egg shapes.

Virgo? Here’s your constellation

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/3xVwEbm

Artist’s concept of the 2 large, hot stars in the Spica system via UA Little Rock.

From a distance of 262 light-years away, Spica appears to us on Earth to be a lone bluish-white star in a quiet region of the sky. But Spica consists of two stars and maybe more. The pair are both larger and hotter than our sun, and they’re separated by only 11 million miles (less than 18 million km), orbiting their common center of gravity in only four days. In contrast, Earth is 93.3 million miles (150 million km, or 1 astronomical unit, aka AU) from our sun, while the two stars in Spica are only .12 AU from each other.

The two stars in the Spica system are individually indistinguishable from a single point of light, even with a telescope. The dual nature of this star was revealed only by analysis of its light with a spectroscope, an instrument that splits light into its component colors.

The star Spica is also called Alpha Virginis, because it’s the brightest star in the constellation Virgo the Maiden. Our eyes see it as distinctly blue-white. Photo by Fred Espenak at AstroPixels.

The two stars are so close, and they orbit so quickly around each other, that their mutual gravity distorts each star into an egg shape. It’s thought that the pointed ends of these egg-shaped stars face each other as they whirl around. Slight magnitude variations may be evidence for such a distortion. The magnitude changes could be the result of the stars showing more or less surface area as they move through different orientations in their orbits.

The pair of stars are both dwarfs brightening near the end of their lifetimes, making them so hot that Spica is considered one of the hottest first magnitude stars. The hottest of the pair is 22,400 Kelvin – blistering compared to the sun’s 5,800 Kelvin – and it may someday explode in a supernova.

The light from Spica’s two stars, taken together, is on average more than 2,200 times brighter than our sun’s light. Their diameters are estimated to be 7.8 and 4 times the sun’s diameter.

Spica is one of several bright stars that the moon can occult (eclipse). Based on observations of how the star’s light is extinguished when the moon passes in front, some astronomers think that it may not just be a spectroscopic binary star. Instead, they feel that there may be as many as three other stars in the system. This would make Spica not a single or even a double, but a quintuple star!

Artist’s concept of Spica from a hypothetical planet. Image via Glyphweb.com

How to find Spica. The best evening views of Spica come from spring to late summer when this star arcs across the southern sky. In the month of May, as seen from the Northern Hemisphere, you’ll find Spica in the southeast in early evening. From the Southern Hemisphere, Spica is closer to due east. From all of Earth in May, as night passes, Spica appears to move westward. Spica rises earlier each evening so that – by the end of August – Spica can be viewed only briefly in the west to west-southwest sky as darkness falls.

Look for the Big Dipper in the northern sky. The Dipper is highest in the sky in northern spring and summer. Notice that the Big Dipper has a bowl and a long, curved handle. Find the Dipper, and then follow the curve of its handle outward, away from the Dipper itself. The first bright star you come to is orange Arcturus, but if you continue past it in the curving path, the next bright star is Spica. Scouts and stargazers remember this trick with the saying: Follow the arc to Arcturus, and speed on (or drive a spike) to Spica.

Spica shines at magnitude 1.04, making it the brightest light in the constellation Virgo the Maiden. Spica is the 15th brightest star visible from anywhere on Earth. It’s virtually the same brightness as Antares in the constellation Scorpius, so sometimes Antares is listed as the 15th and Spica as the 16th brightest. No matter. Identify this beautiful blue-white star with the Big Dipper’s help to spot it in the sky. If you do, this star will be your friend for life.

Use the Big Dipper to “follow the arc to Arcturus” and “drive a spike to Spica.” Read more.

History and mythology of Spica. Spica is from the Latin word for “ear,” and the general connotation is that it refers to an “ear of wheat.” Indeed, the star and the constellation Virgo itself were sometimes associated with the Greek goddess of the harvest, Ceres.

Classical illustration of the constellation Virgo the Maiden, via constellationsofwords.com.

There are many names and stories for Spica’s constellation – Virgo – in mythology, and by association with Spica as well. Fewer stories refer to Spica independently. Many classical references refer to Virgo’s stars as a goddess or with some association with wheat or the harvest, due to the fact that the sun passes through Virgo in the fall. In Greece and Rome she typically was Astraea, the very personification of Justice; or Persephone, daughter of Ceres. In Egypt, Virgo was identified with Isis, and Spica was considered her lute bearer. In ancient China, Spica was a special star of spring known as the Horn.

One Arabic name was Azimech, derived from words meaning Defenseless One or Solitary One. This title may be in reference to Spica’s solitary status with no other bright stars nearby. But Spica is not the most solitary star. That honor goes to Fomalhaut, sometimes called the Autumn Star.

Spica’s position is RA: 13h 25m 12s, dec: -11° 09′ 41″

Bottom line: Spica is the brightest star in Virgo. Spica is at least two stars orbiting extremely close together, distorting each other into egg shapes.

Virgo? Here’s your constellation

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/3xVwEbm

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire