Archaeologist Gabriele Franke of Goethe University, inspecting Nok vessels at the Janjala research station in Nigeria. Franke is a co-author on a new paper about honey-collecting in prehistoric West Africa. Image via Peter Breunig/ University of Bristol.

Terracotta pottery pieces, unearthed at excavation sites in central Nigeria – some as old as 3,500 years – carry direct evidence that the vessels once held honey, humanity’s oldest sweetener. Analyses of residue found in the shards show compounds found in beeswax, suggesting that waxy combs might have been heated in the vessels to separate out the honey. This new knowledge is an exciting find in the world of archeology. Direct evidence from sub-Saharan Africa – related to bees and bee-keeping – has been lacking until now.

The new findings were published on April 14, 2021, in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Communications.

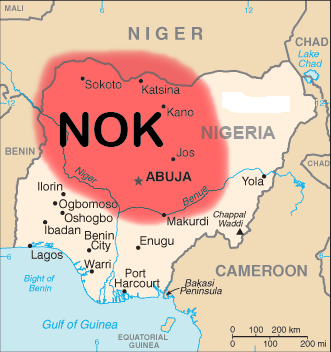

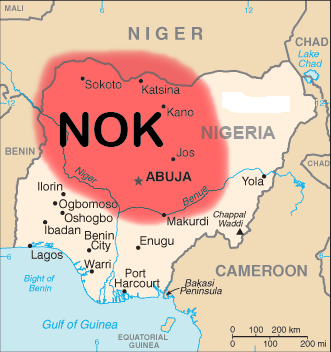

A map showing the ancient Nok territory in modern-day Nigeria. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

The pottery is associated with the Nok culture, a civilization that first arose in 1,500 B.C. and lasted for about 1,500 years. The Nok were known for elaborate terracotta sculptures that were the oldest known figurine art in Africa. The Nok culture was present in a time and place where early farmers and foragers co-existed. But it’s not known, for example, if people of the Nok culture had domesticated animals, or if, instead, they were primarily hunters. Archaeologists have been studying Nok figurines and other artifacts to learn more about this early culture. That includes identifying the foods they ate.

Nok terracotta figurines. Image via Goethe University/ University of Bristol.

At archaeological sites, scientists look for food remains to learn about foraging, hunting, and agricultural practices. For instance, animal bones in the soil offer valuable clues. But at the central Nigeria sites, the acidic soil does not preserve animal remains. So the scientists turned their attention to pottery shards, over 450 pieces, running chemical analyses to look for food residue caught in the porous terracotta.

The scientists were surprised to find that about a third of the pottery pieces contained complex lipids found in beeswax. The beeswax could have been trapped in the vessels’ terracotta pores when it melted during heating, or was absorbed into the pottery during storage of the honeycombs. Stable lipids in the beeswax were then preserved for thousands of years. A chemical analysis technique called gas chromatography was used to identify the lipid compounds as originating from beeswax.

Julie Dunne of the University of Bristol is the new paper’s lead author. She said in a statement:

This is a remarkable example of how biomolecular information extracted from prehistoric pottery, combined with ethnographic data, has provided the first insights into ancient honey hunting in West Africa, 3,500 years ago.

Check out my blog in @NatureEcoEvo on our @NatureComms honey hunting in West Africa 3500 years ago paper #lipids #bees #honey #Nok #Nigeriahttps://t.co/urkVLhXGQh

— Dr Julie Dunne (@thepotlady) April 15, 2021

It’s hard to know for sure how honey was used by the ancient Nok. They most likely heated the combs in the pots to separate out the honey in it. Perhaps the honey was processed with other foods. It’s even possible that the vessels were used for making mead. Beeswax may have been used medicinally, as cosmetics, or for other practical applications like creating a sealant or adhesive. The pottery itself could have been used to house beehives, as is done today by some traditional societies in Africa.

Bees and their association with honey have been featured in prehistoric petroglyphs and paintings. For instance, an 8,000-year-old cave painting in Valencia, Spain, shows a man collecting honey from a wild hive. There are over 4,000 documented instances of prehistoric rock art featuring bees and honey in Africa. According to records maintained by ancient Egyptians, beekeeping was practiced as early as 2,600 B.C. But until now, little was directly known about honey collection in sub-Saharan Africa. Richard Evershed, also of Bristol University and a co-author of the paper, commented in the statement:

The association of prehistoric people with the honeybee is a recurring theme across the ancient world; however, the discovery of the chemical components of beeswax in the pottery of the Nok people provides a unique window on this relationship, when all other sources of evidence are lacking.

Excavation at a Nok site in Ifana, Nigeria. Image via Peter Breunig/ University of Bristol.

Bottom line: The earliest direct evidence of honey collection in sub-Saharan Africa, from 3,500 years ago, was announced by scientists who found residue from beeswax in ancient terracotta pottery associated with the Nok culture of central Nigeria.

Source: Honey-collecting in prehistoric West Africa from 3500 years ago

Read “behind the paper” from its lead author Julie Dunne

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/3e0JV9a

Archaeologist Gabriele Franke of Goethe University, inspecting Nok vessels at the Janjala research station in Nigeria. Franke is a co-author on a new paper about honey-collecting in prehistoric West Africa. Image via Peter Breunig/ University of Bristol.

Terracotta pottery pieces, unearthed at excavation sites in central Nigeria – some as old as 3,500 years – carry direct evidence that the vessels once held honey, humanity’s oldest sweetener. Analyses of residue found in the shards show compounds found in beeswax, suggesting that waxy combs might have been heated in the vessels to separate out the honey. This new knowledge is an exciting find in the world of archeology. Direct evidence from sub-Saharan Africa – related to bees and bee-keeping – has been lacking until now.

The new findings were published on April 14, 2021, in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Communications.

A map showing the ancient Nok territory in modern-day Nigeria. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

The pottery is associated with the Nok culture, a civilization that first arose in 1,500 B.C. and lasted for about 1,500 years. The Nok were known for elaborate terracotta sculptures that were the oldest known figurine art in Africa. The Nok culture was present in a time and place where early farmers and foragers co-existed. But it’s not known, for example, if people of the Nok culture had domesticated animals, or if, instead, they were primarily hunters. Archaeologists have been studying Nok figurines and other artifacts to learn more about this early culture. That includes identifying the foods they ate.

Nok terracotta figurines. Image via Goethe University/ University of Bristol.

At archaeological sites, scientists look for food remains to learn about foraging, hunting, and agricultural practices. For instance, animal bones in the soil offer valuable clues. But at the central Nigeria sites, the acidic soil does not preserve animal remains. So the scientists turned their attention to pottery shards, over 450 pieces, running chemical analyses to look for food residue caught in the porous terracotta.

The scientists were surprised to find that about a third of the pottery pieces contained complex lipids found in beeswax. The beeswax could have been trapped in the vessels’ terracotta pores when it melted during heating, or was absorbed into the pottery during storage of the honeycombs. Stable lipids in the beeswax were then preserved for thousands of years. A chemical analysis technique called gas chromatography was used to identify the lipid compounds as originating from beeswax.

Julie Dunne of the University of Bristol is the new paper’s lead author. She said in a statement:

This is a remarkable example of how biomolecular information extracted from prehistoric pottery, combined with ethnographic data, has provided the first insights into ancient honey hunting in West Africa, 3,500 years ago.

Check out my blog in @NatureEcoEvo on our @NatureComms honey hunting in West Africa 3500 years ago paper #lipids #bees #honey #Nok #Nigeriahttps://t.co/urkVLhXGQh

— Dr Julie Dunne (@thepotlady) April 15, 2021

It’s hard to know for sure how honey was used by the ancient Nok. They most likely heated the combs in the pots to separate out the honey in it. Perhaps the honey was processed with other foods. It’s even possible that the vessels were used for making mead. Beeswax may have been used medicinally, as cosmetics, or for other practical applications like creating a sealant or adhesive. The pottery itself could have been used to house beehives, as is done today by some traditional societies in Africa.

Bees and their association with honey have been featured in prehistoric petroglyphs and paintings. For instance, an 8,000-year-old cave painting in Valencia, Spain, shows a man collecting honey from a wild hive. There are over 4,000 documented instances of prehistoric rock art featuring bees and honey in Africa. According to records maintained by ancient Egyptians, beekeeping was practiced as early as 2,600 B.C. But until now, little was directly known about honey collection in sub-Saharan Africa. Richard Evershed, also of Bristol University and a co-author of the paper, commented in the statement:

The association of prehistoric people with the honeybee is a recurring theme across the ancient world; however, the discovery of the chemical components of beeswax in the pottery of the Nok people provides a unique window on this relationship, when all other sources of evidence are lacking.

Excavation at a Nok site in Ifana, Nigeria. Image via Peter Breunig/ University of Bristol.

Bottom line: The earliest direct evidence of honey collection in sub-Saharan Africa, from 3,500 years ago, was announced by scientists who found residue from beeswax in ancient terracotta pottery associated with the Nok culture of central Nigeria.

Source: Honey-collecting in prehistoric West Africa from 3500 years ago

Read “behind the paper” from its lead author Julie Dunne

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/3e0JV9a

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire