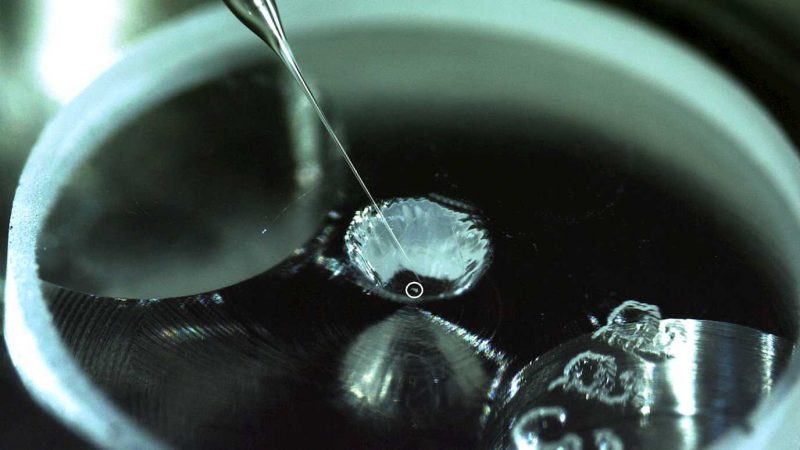

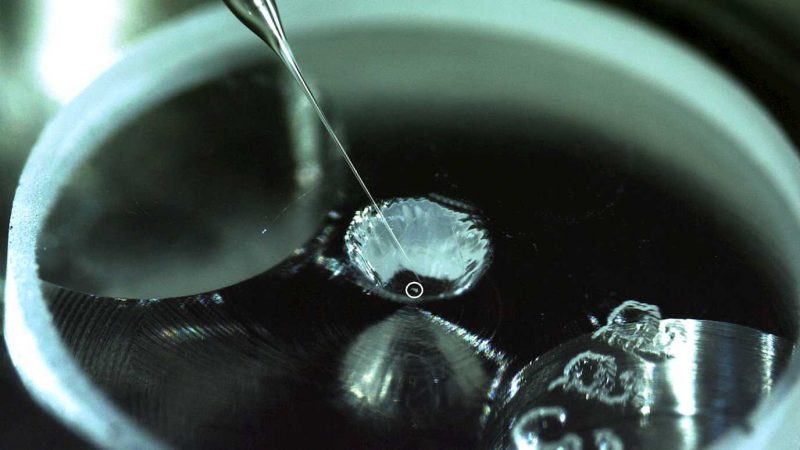

The single grain sample nicknamed Amazon is located in the small white circle in the center of the image. This tiny sample from the asteroid Itokawa confirmed, for the first time, the presence of organic materials and water necessary for life on an asteroid. Image via ISAS/ JAXA/ Royal Holloway.

Asteroids are primordial rocky bodies left over from the formation of the solar system billions of years ago. Some asteroids are rich in carbon, a key building block of life as we know it, and this makes them a prime target for finding clues as to how life first originated on Earth. Now, for the first time, other organic materials essential for life have been found on the surface of an asteroid. These findings, published by scientists at Royal Holloway, University of London, prove that organic materials necessary for life exist on more types of asteroids than previously thought, and are likely common throughout the solar system.

The new research was published in peer-reviewed Scientific Reports on March 4, 2021.

This exciting discovery was made by researchers studying a grain sample from asteroid 25143 Itokawa in the inner solar system, which was visited by Japan’s Hayabusa spacecraft in 2005. The spacecraft landed on the asteroid and collected samples of rock and dust from its surface that it returned to Earth in 2010. These samples have been intensely studied by scientists around the world since then.

What’s significant is that the samples showed evidence that the organic material and water had evolved chemically over time in a way similar to what is thought to have occurred on Earth. This indicates that asteroids can evolve in similar ways to planets even though they are much smaller. Like other asteroids, Itokawa has gone through stages of extreme heating, dehydration and shattering due to impacts from other rocky bodies.

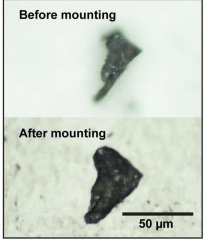

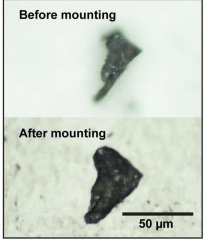

A closer view of the grain-sized sample called Amazon. Image via Q. H. S. Chan et al./ Scientific Reports.

But now we believe that Itokawa was able to assemble again from its fragments and be re-hydrated with water from dust or meteorites.

Water had also previously been found in samples from Itokawa recently, in 2019.

Remarkably, the scientists were able to make these findings from only that one sand-like grain, which was nicknamed Amazon. They found both heated and unheated organic material next to each other in the sample, which provided clues as to how the organic compounds evolved over time. As lead scientist Queenie Chan at Royal Holloway explained:

The Hayabusa mission was a robotic spacecraft developed by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) to return samples from a small near-Earth asteroid named Itokawa, for detailed analysis in laboratories on Earth.

After being studied in great detail by an international team of researchers, our analysis of a single grain, nicknamed ‘Amazon’, has preserved both primitive (unheated) and processed (heated) organic matter within ten microns (a thousandth of a centimeter) of distance.

The organic matter that has been heated indicates that the asteroid had been heated to over 600°C in the past. The presence of unheated organic matter very close to it means that the in-fall of primitive organics arrived on the surface of Itokawa after the asteroid had cooled down.

Scientist Queenie Chan at Royal Holloway led the new research. Image via Royal Holloway.

The discovery will also have an impact on long-held views of the origin of life on Earth, according to the researchers.

Studying ‘Amazon’ has allowed us to better understand how the asteroid constantly evolved by incorporating newly-arrived exogenous water and organic compounds.

These findings are really exciting as they reveal complex details of an asteroid’s history and how its evolution pathway is so similar to that of the prebiotic Earth.

The success of this mission and the analysis of the sample that returned to Earth has since paved the way for a more detailed analysis of carbonaceous material returned by missions such as JAXA’s Hayabusa2 and NASA’s OSIRIS-REx missions. Both of these missions have identified exogenous materials on the target asteroids Ryugu and Bennu, respectively. Our findings suggest that mixing of materials is a common process in our solar system.

Itokawa is an S-type asteroid, meaning it has a siliceous (stony) composition, which is the second most common kind of asteroid. Until now, scientists have focused onC-type asteroids when it comes to studying the origin of life on Earth, since they are rich in organic carbon. They are also the most common type of asteroids in our solar system. But these new results show that S-type asteroids can also contain the organic materials needed for life.

Itokawa is more than 1,000 feet (305 meters) long and between 700 – 1,000 feet (213 – 305 meters) wide, and is the remnant of a once larger body that was about 12 miles (19 km) wide. The parent body was broken apart by impacts. In the aftermath, two of the fragments merged and formed Itokawa, which reached its current size and shape about 8 million years ago.

The asteroid Itokawa as seen by the Japanese spacecraft Hayabusa in 2005. Image via JAXA.

The presence of organics themselves in Itokawa doesn’t prove there was life, but they are the building blocks of life as we know it. The latest findings seem to imply that such organic materials are common throughout our solar system, increasing the chances that perhaps life could be found elsewhere as well, even if only as microbes.

Japan’s second asteroid sampling mission, Hyabusa2, successfully brought back samples from the asteroid Ryugu. Those samples were delivered to Earth on December 6, 2020. Ryugu is a C-type asteroid, meaning it has an abundancy of carbon. Only a few grams of surface material was collected, but that is still more than what was obtained at Itokawa.

As with Itokawa, those samples are being carefully studied to see what organic compounds they contain, such as amino acids, which proteins in earthly life are made of. By the end of 2021, JAXA will disperse samples of Ryugu to six teams of scientists around the globe.

Similar to Itokawa, Ryugu is also a fragment of a once larger asteroid.

Hayabusa photographed its own shadow on Itokawa in 2005. Image via JAXA/ NASA.

On October 20, 2020, NASA’s OSIRIS-REx spacecraft successfully acquired samples from the asteroid Bennu. OSIRIS-REx is scheduled to return those samples to Earth on September 24, 2023. Bennu is a more rare primitive B-type asteroid about 500 meters in diameter and is expected to also contain both organic compounds and water.

Bottom line: For the first time, scientists have confirmed the presence of organic materials essential for life on the surface of an asteroid.

Source: Organic matter and water from asteroid Itokawa

Via Royal Holloway, University of London

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/3tq4fXP

The single grain sample nicknamed Amazon is located in the small white circle in the center of the image. This tiny sample from the asteroid Itokawa confirmed, for the first time, the presence of organic materials and water necessary for life on an asteroid. Image via ISAS/ JAXA/ Royal Holloway.

Asteroids are primordial rocky bodies left over from the formation of the solar system billions of years ago. Some asteroids are rich in carbon, a key building block of life as we know it, and this makes them a prime target for finding clues as to how life first originated on Earth. Now, for the first time, other organic materials essential for life have been found on the surface of an asteroid. These findings, published by scientists at Royal Holloway, University of London, prove that organic materials necessary for life exist on more types of asteroids than previously thought, and are likely common throughout the solar system.

The new research was published in peer-reviewed Scientific Reports on March 4, 2021.

This exciting discovery was made by researchers studying a grain sample from asteroid 25143 Itokawa in the inner solar system, which was visited by Japan’s Hayabusa spacecraft in 2005. The spacecraft landed on the asteroid and collected samples of rock and dust from its surface that it returned to Earth in 2010. These samples have been intensely studied by scientists around the world since then.

What’s significant is that the samples showed evidence that the organic material and water had evolved chemically over time in a way similar to what is thought to have occurred on Earth. This indicates that asteroids can evolve in similar ways to planets even though they are much smaller. Like other asteroids, Itokawa has gone through stages of extreme heating, dehydration and shattering due to impacts from other rocky bodies.

A closer view of the grain-sized sample called Amazon. Image via Q. H. S. Chan et al./ Scientific Reports.

But now we believe that Itokawa was able to assemble again from its fragments and be re-hydrated with water from dust or meteorites.

Water had also previously been found in samples from Itokawa recently, in 2019.

Remarkably, the scientists were able to make these findings from only that one sand-like grain, which was nicknamed Amazon. They found both heated and unheated organic material next to each other in the sample, which provided clues as to how the organic compounds evolved over time. As lead scientist Queenie Chan at Royal Holloway explained:

The Hayabusa mission was a robotic spacecraft developed by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) to return samples from a small near-Earth asteroid named Itokawa, for detailed analysis in laboratories on Earth.

After being studied in great detail by an international team of researchers, our analysis of a single grain, nicknamed ‘Amazon’, has preserved both primitive (unheated) and processed (heated) organic matter within ten microns (a thousandth of a centimeter) of distance.

The organic matter that has been heated indicates that the asteroid had been heated to over 600°C in the past. The presence of unheated organic matter very close to it means that the in-fall of primitive organics arrived on the surface of Itokawa after the asteroid had cooled down.

Scientist Queenie Chan at Royal Holloway led the new research. Image via Royal Holloway.

The discovery will also have an impact on long-held views of the origin of life on Earth, according to the researchers.

Studying ‘Amazon’ has allowed us to better understand how the asteroid constantly evolved by incorporating newly-arrived exogenous water and organic compounds.

These findings are really exciting as they reveal complex details of an asteroid’s history and how its evolution pathway is so similar to that of the prebiotic Earth.

The success of this mission and the analysis of the sample that returned to Earth has since paved the way for a more detailed analysis of carbonaceous material returned by missions such as JAXA’s Hayabusa2 and NASA’s OSIRIS-REx missions. Both of these missions have identified exogenous materials on the target asteroids Ryugu and Bennu, respectively. Our findings suggest that mixing of materials is a common process in our solar system.

Itokawa is an S-type asteroid, meaning it has a siliceous (stony) composition, which is the second most common kind of asteroid. Until now, scientists have focused onC-type asteroids when it comes to studying the origin of life on Earth, since they are rich in organic carbon. They are also the most common type of asteroids in our solar system. But these new results show that S-type asteroids can also contain the organic materials needed for life.

Itokawa is more than 1,000 feet (305 meters) long and between 700 – 1,000 feet (213 – 305 meters) wide, and is the remnant of a once larger body that was about 12 miles (19 km) wide. The parent body was broken apart by impacts. In the aftermath, two of the fragments merged and formed Itokawa, which reached its current size and shape about 8 million years ago.

The asteroid Itokawa as seen by the Japanese spacecraft Hayabusa in 2005. Image via JAXA.

The presence of organics themselves in Itokawa doesn’t prove there was life, but they are the building blocks of life as we know it. The latest findings seem to imply that such organic materials are common throughout our solar system, increasing the chances that perhaps life could be found elsewhere as well, even if only as microbes.

Japan’s second asteroid sampling mission, Hyabusa2, successfully brought back samples from the asteroid Ryugu. Those samples were delivered to Earth on December 6, 2020. Ryugu is a C-type asteroid, meaning it has an abundancy of carbon. Only a few grams of surface material was collected, but that is still more than what was obtained at Itokawa.

As with Itokawa, those samples are being carefully studied to see what organic compounds they contain, such as amino acids, which proteins in earthly life are made of. By the end of 2021, JAXA will disperse samples of Ryugu to six teams of scientists around the globe.

Similar to Itokawa, Ryugu is also a fragment of a once larger asteroid.

Hayabusa photographed its own shadow on Itokawa in 2005. Image via JAXA/ NASA.

On October 20, 2020, NASA’s OSIRIS-REx spacecraft successfully acquired samples from the asteroid Bennu. OSIRIS-REx is scheduled to return those samples to Earth on September 24, 2023. Bennu is a more rare primitive B-type asteroid about 500 meters in diameter and is expected to also contain both organic compounds and water.

Bottom line: For the first time, scientists have confirmed the presence of organic materials essential for life on the surface of an asteroid.

Source: Organic matter and water from asteroid Itokawa

Via Royal Holloway, University of London

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/3tq4fXP

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire