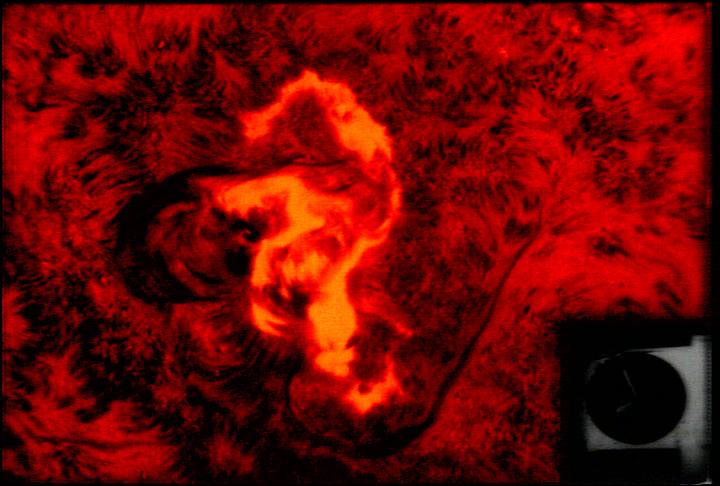

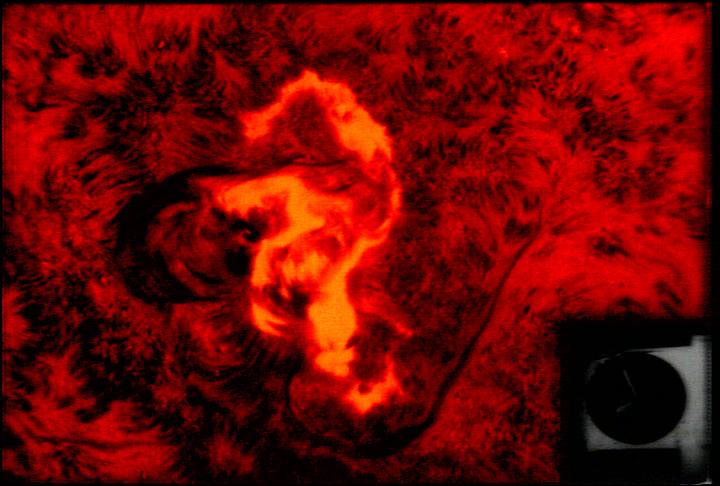

This seahorse-shaped solar flare erupted from an active region on the sun on August 7, 1972. It was one of a number of powerful solar storms in 1972 that caused earthly effects: for example, widespread electrical and communication grid disturbances through large portions of North America as well as satellite disruptions. Image via NASA/ Big Bear Observatory.

Powerful solar storms can hammer Earth, causing major technology glitches. One of the best-remembered events is the Quebec power grid failure of 1989, a 12-hour blackout in which millions of people found themselves in dark office buildings, stalled elevators, and underground pedestrian tunnels. Going farther back, there’s the famous Carrington Event of 1859, which fried telegraph wires. Scientists agree it’s only a matter of time until the next powerful solar storm affects earthly technologies. Next time, we might expect steeper consequences, since today’s world relies so heavily on technology. But, with few events to go on, no one knows when the next powerful Earth-directed event will erupt on the sun. That’s one reason researchers were happy to announce in March 2021 that they’ve unearthed new eyewitness accounts from a 1582 solar storm that startled skywatchers across the globe.

Pero Ruiz Soares was a 16th-century Portuguese author in Lisbon. He and his contemporaries were unaware of the connection between solar storms and the northern lights when he wrote of the 1582 event:

A great fire appeared in the sky to the north, and lasted three nights.

All that part of the sky appeared burning in fiery flames; it seemed that the sky was burning. Nobody remembered having seen something like that … At midnight, great fire rays arose above the castle which were dreadful and fearful. The following day, it happened the same at the same hour but it was not so great and terrifying. Everybody went to the countryside to see this great sign.

According to a statement from scientists who studied the event:

Across the globe in feudal Japan, observers in Kyoto noted the same fiery red display in their skies, too. Similar accounts of strange nighttime lights were recorded in Leipzig, Germany; Yecheon, South Korea; and a dozen other cities across Europe and East Asia.

During those few days in 1582, people looking skyward – not understanding what they saw – were marveling at a strong display of the northern lights, or aurora borealis, which was little understood at the time and the subject of many myths and legends. The northern lights are seen mostly at high latitudes on Earth. They’re not often seen at lower latitudes, like Portugal. That’s another thing a powerful solar storm can do, however; it can cause northern lights to be seen closer to Earth’s equator.

Today’s researchers look to uncover events in the past, such as the 1582 solar storm, in order to investigate the pattern of these strong storms on the sun. They want to know how often they occur. They hope historical records, like that of the 1582 storm, will help them predict future solar storms. At present, with scientists’ limited understanding of the patterns, the historical record suggests that such powerful Earth-sun events occur at least once a century. Their statement said:

The historical record seems to suggest that major storms like the one in 1582 are, at minimum, a once-in-a-century occurrence, and so we should expect one or more of them to hit Earth in the 21st century.

This 2010 aurora resulted from a coronal mass ejection, an event that can ripple through our solar system after a powerful solar storm. Astronauts on the International Space Station (ISS) photographed the amazing show. Astronauts are vulnerable to solar storms, by the way, especially while performing spacewalks, or moving around unshielded on, say, the surface of the moon. In August 1972, between the April Apollo 16 moon mission and December Apollo 17 moon mission, the sun unleashed a solar storm with enough radiation that would have killed moon-walking astronauts. Image via NASA/ ISS Expedition 23 Crew.

The sun waxes and wanes in activity on about an 11-year cycle. Solar Cycle 25 officially began in late 2020. In other words, we’re heading toward another solar maximum, when the sun should be at its most active. Scientists expect this solar maximum to occur around 2025.

In the coming few years, we can expect Earth to undergo some effects as activity on the sun increases. At the peak of the sun’s activity, charged particles from the sun may affect satellites in orbit, and may disrupt communications or navigation on Earth. But, for the most part, these effects are expected to be manageable.

In the meantime, scientists are looking out for the next truly big solar storm. For example, Rami Qahwaji of the University of Bradford wrote at The Conversation:

My colleagues and I developed a real-time automated computer system which uses image processing and artificial intelligence technologies to monitor and analyze solar satellite data. This helps predict the likelihood of solar flares in the coming 24 hours.

This team has also created a process for automatically classifying sunspots and detecting different solar features, such as active regions and sunspots. Their space weather prediction system is publicly available here.

How else can you learn about activity on the sun? NASA has a whole fleet of spacecraft aimed sunward. Go to NASA Heliophysics.

Another wonderful place for information about solar storms is the website SpaceWeather.com. There, you’ll find daily updates on the day-to-day activity on the sun, which can be expected to increase in the coming few years.

You might also try NOAA’s SpaceWeather Prediction Center.

During a strong solar storm, auroras will appear much farther south than usual and shine so brightly that they illuminate the ground below. During the 1859 Carrington Event, auroras shone so brightly in the nighttime sky that birds began tweeting and people rose to start their daily chores, believing the sun was rising. Image via v2osk/ Unsplash.

Bottom line: In March 2021, scientists said they’ve unearthed new eyewitness accounts from a 1582 solar storm that startled skywatchers across the globe. They were glad to have these reports, which might help them understand long-term patterns in solar activity, as it affects Earth.

Source: Portuguese eyewitness accounts of the great space weather event of 1582

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/39rkITR

This seahorse-shaped solar flare erupted from an active region on the sun on August 7, 1972. It was one of a number of powerful solar storms in 1972 that caused earthly effects: for example, widespread electrical and communication grid disturbances through large portions of North America as well as satellite disruptions. Image via NASA/ Big Bear Observatory.

Powerful solar storms can hammer Earth, causing major technology glitches. One of the best-remembered events is the Quebec power grid failure of 1989, a 12-hour blackout in which millions of people found themselves in dark office buildings, stalled elevators, and underground pedestrian tunnels. Going farther back, there’s the famous Carrington Event of 1859, which fried telegraph wires. Scientists agree it’s only a matter of time until the next powerful solar storm affects earthly technologies. Next time, we might expect steeper consequences, since today’s world relies so heavily on technology. But, with few events to go on, no one knows when the next powerful Earth-directed event will erupt on the sun. That’s one reason researchers were happy to announce in March 2021 that they’ve unearthed new eyewitness accounts from a 1582 solar storm that startled skywatchers across the globe.

Pero Ruiz Soares was a 16th-century Portuguese author in Lisbon. He and his contemporaries were unaware of the connection between solar storms and the northern lights when he wrote of the 1582 event:

A great fire appeared in the sky to the north, and lasted three nights.

All that part of the sky appeared burning in fiery flames; it seemed that the sky was burning. Nobody remembered having seen something like that … At midnight, great fire rays arose above the castle which were dreadful and fearful. The following day, it happened the same at the same hour but it was not so great and terrifying. Everybody went to the countryside to see this great sign.

According to a statement from scientists who studied the event:

Across the globe in feudal Japan, observers in Kyoto noted the same fiery red display in their skies, too. Similar accounts of strange nighttime lights were recorded in Leipzig, Germany; Yecheon, South Korea; and a dozen other cities across Europe and East Asia.

During those few days in 1582, people looking skyward – not understanding what they saw – were marveling at a strong display of the northern lights, or aurora borealis, which was little understood at the time and the subject of many myths and legends. The northern lights are seen mostly at high latitudes on Earth. They’re not often seen at lower latitudes, like Portugal. That’s another thing a powerful solar storm can do, however; it can cause northern lights to be seen closer to Earth’s equator.

Today’s researchers look to uncover events in the past, such as the 1582 solar storm, in order to investigate the pattern of these strong storms on the sun. They want to know how often they occur. They hope historical records, like that of the 1582 storm, will help them predict future solar storms. At present, with scientists’ limited understanding of the patterns, the historical record suggests that such powerful Earth-sun events occur at least once a century. Their statement said:

The historical record seems to suggest that major storms like the one in 1582 are, at minimum, a once-in-a-century occurrence, and so we should expect one or more of them to hit Earth in the 21st century.

This 2010 aurora resulted from a coronal mass ejection, an event that can ripple through our solar system after a powerful solar storm. Astronauts on the International Space Station (ISS) photographed the amazing show. Astronauts are vulnerable to solar storms, by the way, especially while performing spacewalks, or moving around unshielded on, say, the surface of the moon. In August 1972, between the April Apollo 16 moon mission and December Apollo 17 moon mission, the sun unleashed a solar storm with enough radiation that would have killed moon-walking astronauts. Image via NASA/ ISS Expedition 23 Crew.

The sun waxes and wanes in activity on about an 11-year cycle. Solar Cycle 25 officially began in late 2020. In other words, we’re heading toward another solar maximum, when the sun should be at its most active. Scientists expect this solar maximum to occur around 2025.

In the coming few years, we can expect Earth to undergo some effects as activity on the sun increases. At the peak of the sun’s activity, charged particles from the sun may affect satellites in orbit, and may disrupt communications or navigation on Earth. But, for the most part, these effects are expected to be manageable.

In the meantime, scientists are looking out for the next truly big solar storm. For example, Rami Qahwaji of the University of Bradford wrote at The Conversation:

My colleagues and I developed a real-time automated computer system which uses image processing and artificial intelligence technologies to monitor and analyze solar satellite data. This helps predict the likelihood of solar flares in the coming 24 hours.

This team has also created a process for automatically classifying sunspots and detecting different solar features, such as active regions and sunspots. Their space weather prediction system is publicly available here.

How else can you learn about activity on the sun? NASA has a whole fleet of spacecraft aimed sunward. Go to NASA Heliophysics.

Another wonderful place for information about solar storms is the website SpaceWeather.com. There, you’ll find daily updates on the day-to-day activity on the sun, which can be expected to increase in the coming few years.

You might also try NOAA’s SpaceWeather Prediction Center.

During a strong solar storm, auroras will appear much farther south than usual and shine so brightly that they illuminate the ground below. During the 1859 Carrington Event, auroras shone so brightly in the nighttime sky that birds began tweeting and people rose to start their daily chores, believing the sun was rising. Image via v2osk/ Unsplash.

Bottom line: In March 2021, scientists said they’ve unearthed new eyewitness accounts from a 1582 solar storm that startled skywatchers across the globe. They were glad to have these reports, which might help them understand long-term patterns in solar activity, as it affects Earth.

Source: Portuguese eyewitness accounts of the great space weather event of 1582

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/39rkITR

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire