Artemis moon program logo and graphic via NASA.

NASA’s ongoing Artemis mission – a mission to return humans to the moon by 2024 – got a positive mention in a White House press briefing this week (February 4, 2021), a welcome boost to those waiting to hear how Artemis will fare under the new Joe Biden administration. During the briefing, White House press secretary Jen Psaki (@PressSec on Twitter) said:

… I’m very excited about it now to tell my daughter all about it.

So, for those of you who have not been following it as closely: Through the Artemis program, the United States government will work with industry and international partners to send astronauts to the surface of the moon – another man and a woman to the moon – which is very exciting; conduct new and exciting science; prepare for future missions to Mars; and demonstrate America’s values.

To date, only 12 humans have walked on the moon; that was half a century ago. The Artemis program, a waypoint to Mars, provides exactly the opportunity to add numbers to that, of course. Lunar exploration has broad and bicameral support in Congress, most recently detailed in the FY2021 omnibus spending bill. And certainly we support this effort and endeavor.

Watch the entire February 4 press briefing on YouTube, or read the official transcript.

The idea to launch the first man since 1972, and the first woman, to the moon – with the mission originally aimed at a 2024 landing – came from the Trump administration. The Democratic Party platform – a practical list of Democratic Party objectives for the next four years – announced in summer 2020 had a brief mention of Artemis, along with other space priorities:

Democrats continue to support NASA and are committed to continuing space exploration and discovery. We believe in continuing the spirit of discovery that has animated NASA’s human space exploration, in addition to its scientific and medical research, technological innovation, and educational mission that allows us to better understand our own planet and place in the universe. We will strengthen support for the United States’ role in space through our continued presence on the International Space Station, working in partnership with the international community to continue scientific and medical innovation. We support NASA’s work to return Americans to the moon and go beyond to Mars, taking the next step in exploring our solar system. Democrats additionally support strengthening NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Earth observation missions to better understand how climate change is impacting our home planet.

However, despite technical challenges that many have suggested will delay the Artemis mission, no newly scheduled date – other than the 2024 date – has been announced for sending humans back to the moon.

There has been speculation that the Biden administration would, at the very least, slow down the Artemis program, perhaps freeing up money for Earth science and other priorities elsewhere in the agency. On December 20, 2020 – as mentioned by Psaki in her February 4 comments – the United States government’s two houses of Congress agreed on NASA’s final budget for fiscal year 2021. In the report accompanying the bill, Senate appropriators noted that it is:

… difficult to analyze the future impacts that funding the accelerated moon mission will have on NASA’s other important missions.

But now 2021 is here, and, once again, the Biden administration has confirmed its support for Artemis. That is music to the ears of those longing to send humans beyond Earth orbit again, for the first time in decades.

An Orion spacecraft, traveling by truck, passes the Vehicle Assembly Building at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station on November 11, 2014. Image via Tampa Bay Times.

All indications so far are that the first Artemis mission, an uncrewed mission, is still scheduled for launch in November 2021 from the agency’s Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Florida. That mission will be Artemis 1. That’s despite a reported component failure on the cone-shaped Orion space capsule, the vehicle that ultimately will carry astronauts back to the moon.

The November 2021 launch will be a test of both the Orion capsule and the rocket intended to launch it, called the SLS, or Space Launch System.

The second Artemis mission – planned for 2023 – will test Orion’s critical systems with humans aboard. It’s expected to be the first crewed mission to travel beyond low Earth orbit since Apollo 17 in 1972.

Then will come the Artemis 3 mission, the one expected to carry astronauts back to the moon, hopefully in 2024. The Artemis program is part of Donald Trump’s Space Policy Directive 1, approved in December 2017. The stated goal is to return American astronauts to the moon for the first time since 1972 and to:

… establish a foundation for an eventual mission to Mars.

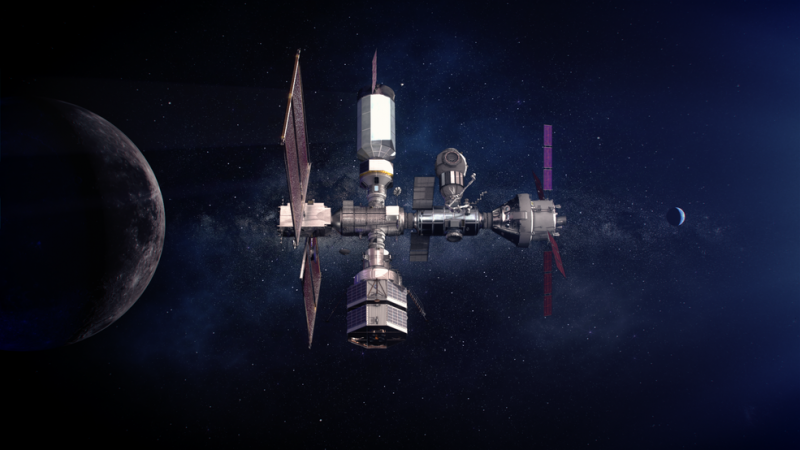

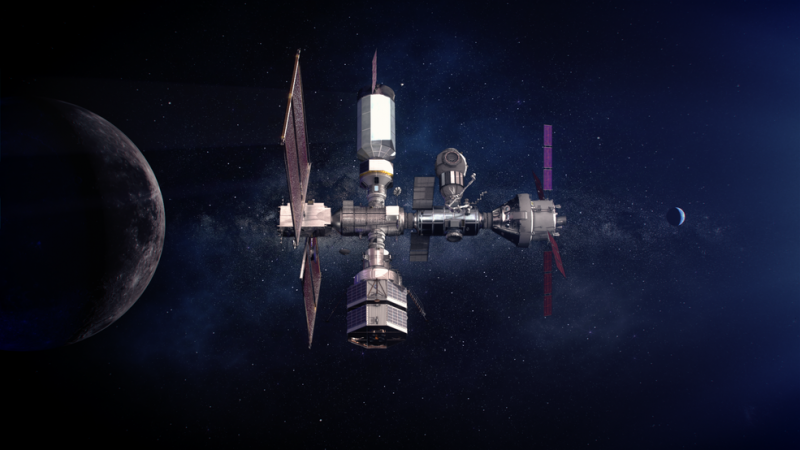

Illustration of the orbiting Gateway lunar outpost, a planned space station in lunar orbit, intended for use in astronaut missions to the moon and later Mars. The plan is to build it with commercial and international partners. NASA has said, “… the Gateway is critical to sustainable lunar exploration and will serve as a model for future missions to Mars.” Read more about Gateway.

In the Artemis 1 mission, the crew module Orion and SLS rocket are expected to launch together from Kennedy Space Center’s historic Launch Complex 39B. The SLS – a rocket more powerful than the Saturn V that propelled the Apollo astronauts to the moon – will produce 8.8 million pounds of thrust (39 million newtons) with its five boosters and four engines during liftoff to bring 6 million pounds (2.7 million kg) of vehicle into orbit.

After releasing the boosters, the engines will shut down and the core stage (main body) of the rocket will separate from the spacecraft.

Following that are a series of technical propulsion stages that will give Orion the brawn needed to leave Earth’s orbit and head in the direction of the moon, but not before dropping off a number of small satellites called CubeSats while on its way. These CubeSats will perform a series of experiments and demonstrations unrelated to the Artemis mission in deep space, such as exposing living microorganisms to a deep space radiation environment for the first time in more than 40 years.

An artist’s rendering of SLS Block 1 with Orion spacecraft on the pad before launch. Image via Wikipedia.

Once in lunar orbit, Orion will collect data and enable mission controllers to assess its performance for about a week. When ready to return home, Orion will use its in-space propulsion system provided by the European Space Agency (ESA), together with the moon’s gravity, to head back to Earth.

The ESA service module will provide – apart from in-space propulsion – power, air and water for the astronauts of the future missions.

About three weeks and more than 1.3 million miles (2.1 million km) later, the Artemis 1 mission will end with a test of Orion’s return capabilities by directing it to land near a recovery ship off the coast of Baja, California. All of this might sound like a lot of intricate, technical work. The NASA video below illustrates the entire Artemis 1 mission.

The coronavirus pandemic slowed down the testing of SLS, but the process has now resumed at the agency’s Stennis Space Center in Mississippi. Although a hot fire test earlier this year – January 16, 2021 – did not go as planned, NASA has since announced via the Artemis blog that a second test could happen in the fourth week of February. The hot fire is the final test of the Green Run test series, a comprehensive assessment of the Space Launch System’s core stage before launching the Artemis 1 mission.

Testing delays like the one that happened with the January hot fire test leave little margin to keep things on track for the Artemis 1 launch in late 2021.

After the hot fire test, the core stage will be refurbished and brought to NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida for even more tests. The development of Orion, led by Lockheed Martin and Airbus Defense and Space, has encountered its own delays, although the spacecraft is on track to begin Artemis 1 launch preparations in the first part of 2021.

The second mission – the crewed Orion capsule test mission, Artemis 2 – is scheduled for August 2023.

Future crewed exploration missions onboard Orion will dock with Gateway, an outpost NASA plans to build in orbit around the moon to support sustainable, long-term human return to the lunar surface. NASA lunar director Marshall Smith said:

We don’t need to take the giant leap all at one time. For a future mission, after we demonstrate that we can get to the moon and get a lander to work, we can then have them both dock with the Gateway.

Meanwhile, in early December 2020, NASA announced that it has selected 18 astronauts from its corps to form what it’s calling the Artemis Team. Two of these astronauts are expected to become the first American man and woman to return to the moon since 1972. NASA said then it will announce flight assignments for astronauts later, pulling from the Artemis Team.

The Artemis program, by the way, is named for the sister to the sun-god, Apollo, in Greek mythology.

You’ll find names and brief bios for the Artemis Team members here.

Bottom line: During a White House press briefing on February 4, 2021, White House press secretary Jen Psaki confirmed the Biden administration’s support fo NASA’s Artemis program, whose long-term goal is to send the next man and first woman to the moon by 2024. The program has had some technical setbacks, but – at this writing – the first launch in the series, Artemis 1, is still scheduled for late 2021.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/3mdiJWR

Artemis moon program logo and graphic via NASA.

NASA’s ongoing Artemis mission – a mission to return humans to the moon by 2024 – got a positive mention in a White House press briefing this week (February 4, 2021), a welcome boost to those waiting to hear how Artemis will fare under the new Joe Biden administration. During the briefing, White House press secretary Jen Psaki (@PressSec on Twitter) said:

… I’m very excited about it now to tell my daughter all about it.

So, for those of you who have not been following it as closely: Through the Artemis program, the United States government will work with industry and international partners to send astronauts to the surface of the moon – another man and a woman to the moon – which is very exciting; conduct new and exciting science; prepare for future missions to Mars; and demonstrate America’s values.

To date, only 12 humans have walked on the moon; that was half a century ago. The Artemis program, a waypoint to Mars, provides exactly the opportunity to add numbers to that, of course. Lunar exploration has broad and bicameral support in Congress, most recently detailed in the FY2021 omnibus spending bill. And certainly we support this effort and endeavor.

Watch the entire February 4 press briefing on YouTube, or read the official transcript.

The idea to launch the first man since 1972, and the first woman, to the moon – with the mission originally aimed at a 2024 landing – came from the Trump administration. The Democratic Party platform – a practical list of Democratic Party objectives for the next four years – announced in summer 2020 had a brief mention of Artemis, along with other space priorities:

Democrats continue to support NASA and are committed to continuing space exploration and discovery. We believe in continuing the spirit of discovery that has animated NASA’s human space exploration, in addition to its scientific and medical research, technological innovation, and educational mission that allows us to better understand our own planet and place in the universe. We will strengthen support for the United States’ role in space through our continued presence on the International Space Station, working in partnership with the international community to continue scientific and medical innovation. We support NASA’s work to return Americans to the moon and go beyond to Mars, taking the next step in exploring our solar system. Democrats additionally support strengthening NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Earth observation missions to better understand how climate change is impacting our home planet.

However, despite technical challenges that many have suggested will delay the Artemis mission, no newly scheduled date – other than the 2024 date – has been announced for sending humans back to the moon.

There has been speculation that the Biden administration would, at the very least, slow down the Artemis program, perhaps freeing up money for Earth science and other priorities elsewhere in the agency. On December 20, 2020 – as mentioned by Psaki in her February 4 comments – the United States government’s two houses of Congress agreed on NASA’s final budget for fiscal year 2021. In the report accompanying the bill, Senate appropriators noted that it is:

… difficult to analyze the future impacts that funding the accelerated moon mission will have on NASA’s other important missions.

But now 2021 is here, and, once again, the Biden administration has confirmed its support for Artemis. That is music to the ears of those longing to send humans beyond Earth orbit again, for the first time in decades.

An Orion spacecraft, traveling by truck, passes the Vehicle Assembly Building at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station on November 11, 2014. Image via Tampa Bay Times.

All indications so far are that the first Artemis mission, an uncrewed mission, is still scheduled for launch in November 2021 from the agency’s Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Florida. That mission will be Artemis 1. That’s despite a reported component failure on the cone-shaped Orion space capsule, the vehicle that ultimately will carry astronauts back to the moon.

The November 2021 launch will be a test of both the Orion capsule and the rocket intended to launch it, called the SLS, or Space Launch System.

The second Artemis mission – planned for 2023 – will test Orion’s critical systems with humans aboard. It’s expected to be the first crewed mission to travel beyond low Earth orbit since Apollo 17 in 1972.

Then will come the Artemis 3 mission, the one expected to carry astronauts back to the moon, hopefully in 2024. The Artemis program is part of Donald Trump’s Space Policy Directive 1, approved in December 2017. The stated goal is to return American astronauts to the moon for the first time since 1972 and to:

… establish a foundation for an eventual mission to Mars.

Illustration of the orbiting Gateway lunar outpost, a planned space station in lunar orbit, intended for use in astronaut missions to the moon and later Mars. The plan is to build it with commercial and international partners. NASA has said, “… the Gateway is critical to sustainable lunar exploration and will serve as a model for future missions to Mars.” Read more about Gateway.

In the Artemis 1 mission, the crew module Orion and SLS rocket are expected to launch together from Kennedy Space Center’s historic Launch Complex 39B. The SLS – a rocket more powerful than the Saturn V that propelled the Apollo astronauts to the moon – will produce 8.8 million pounds of thrust (39 million newtons) with its five boosters and four engines during liftoff to bring 6 million pounds (2.7 million kg) of vehicle into orbit.

After releasing the boosters, the engines will shut down and the core stage (main body) of the rocket will separate from the spacecraft.

Following that are a series of technical propulsion stages that will give Orion the brawn needed to leave Earth’s orbit and head in the direction of the moon, but not before dropping off a number of small satellites called CubeSats while on its way. These CubeSats will perform a series of experiments and demonstrations unrelated to the Artemis mission in deep space, such as exposing living microorganisms to a deep space radiation environment for the first time in more than 40 years.

An artist’s rendering of SLS Block 1 with Orion spacecraft on the pad before launch. Image via Wikipedia.

Once in lunar orbit, Orion will collect data and enable mission controllers to assess its performance for about a week. When ready to return home, Orion will use its in-space propulsion system provided by the European Space Agency (ESA), together with the moon’s gravity, to head back to Earth.

The ESA service module will provide – apart from in-space propulsion – power, air and water for the astronauts of the future missions.

About three weeks and more than 1.3 million miles (2.1 million km) later, the Artemis 1 mission will end with a test of Orion’s return capabilities by directing it to land near a recovery ship off the coast of Baja, California. All of this might sound like a lot of intricate, technical work. The NASA video below illustrates the entire Artemis 1 mission.

The coronavirus pandemic slowed down the testing of SLS, but the process has now resumed at the agency’s Stennis Space Center in Mississippi. Although a hot fire test earlier this year – January 16, 2021 – did not go as planned, NASA has since announced via the Artemis blog that a second test could happen in the fourth week of February. The hot fire is the final test of the Green Run test series, a comprehensive assessment of the Space Launch System’s core stage before launching the Artemis 1 mission.

Testing delays like the one that happened with the January hot fire test leave little margin to keep things on track for the Artemis 1 launch in late 2021.

After the hot fire test, the core stage will be refurbished and brought to NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida for even more tests. The development of Orion, led by Lockheed Martin and Airbus Defense and Space, has encountered its own delays, although the spacecraft is on track to begin Artemis 1 launch preparations in the first part of 2021.

The second mission – the crewed Orion capsule test mission, Artemis 2 – is scheduled for August 2023.

Future crewed exploration missions onboard Orion will dock with Gateway, an outpost NASA plans to build in orbit around the moon to support sustainable, long-term human return to the lunar surface. NASA lunar director Marshall Smith said:

We don’t need to take the giant leap all at one time. For a future mission, after we demonstrate that we can get to the moon and get a lander to work, we can then have them both dock with the Gateway.

Meanwhile, in early December 2020, NASA announced that it has selected 18 astronauts from its corps to form what it’s calling the Artemis Team. Two of these astronauts are expected to become the first American man and woman to return to the moon since 1972. NASA said then it will announce flight assignments for astronauts later, pulling from the Artemis Team.

The Artemis program, by the way, is named for the sister to the sun-god, Apollo, in Greek mythology.

You’ll find names and brief bios for the Artemis Team members here.

Bottom line: During a White House press briefing on February 4, 2021, White House press secretary Jen Psaki confirmed the Biden administration’s support fo NASA’s Artemis program, whose long-term goal is to send the next man and first woman to the moon by 2024. The program has had some technical setbacks, but – at this writing – the first launch in the series, Artemis 1, is still scheduled for late 2021.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/3mdiJWR

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire