Watch for the waning crescent moon to pair up with red Antares, the brightest star in the constellation Scorpius the Scorpion, on the morning of February 6, 2021. After that, you might try your luck at catching the Venus-Saturn conjunction – also February 6 – but in a bright morning twilight sky. Be aware that Antares and the moon will be easy to see, and Venus and Saturn will be hard to see, even with binoculars.

What’s more – after Antares has disappeared in the light of the coming sunrise – the lit side of the moon will still be visible, and it’ll still be pointing more or less toward the horizon, toward two other planets that you might or might not see, Jupiter and Saturn. They are both just now entering the morning sky, having dazzled us all with their Great Conjunction in the evening sky in December 2020. Jupiter is very bright, second only to Venus among the planets. Still, all of these planets are very near the sunrise glare. You might not see any of them.

Read more: Moon and morning planets February 8, 9 and 10

Read more: EarthSky’s February 2021 guide to the bright planets

Maybe you can’t see any of these planets right now. If not, be sure to get up early enough to see and contemplate mighty Antares near the moon. It’ll look like a pinpoint of light. But Antares is a huge red supergiant star, with some 15 to 18 times our sun’s mass. It’s a truly enormous star, with a radius in excess of three astronomical units, or three times Earth’s average distance from the sun. If, by some bit of magic, Antares were suddenly substituted for our sun, its surface would consume the Earth and extend well past the orbit of Mars!

Unlike red dwarf stars (discussed below), the lifespan of supergiant stars is short (by stellar standards). Antares is only about 12 million years old, and already well into the autumn of its years. That’s in contrast to our sun, which is 4.5 billion years old, and only middle-aged.

Notice the ruddy color of Antares. It indicates a low surface temperature of about 3,500 kelvins (5,800 degrees F or 3,200 C). That’s in contrast to a surface temperature of about 6,000 kelvins (10,000 F or 5,500 C) for our yellow-colored sun. Or contrast Antares to a very hot star, like blue-white Spica in the constellation Virgo the Maiden. Spica boasts a surface temperature of around 22,400 kelvins (39,900 F or 22,100 C).

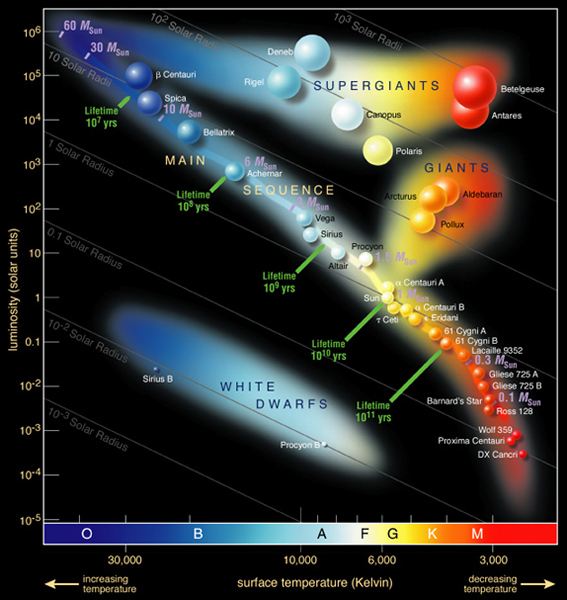

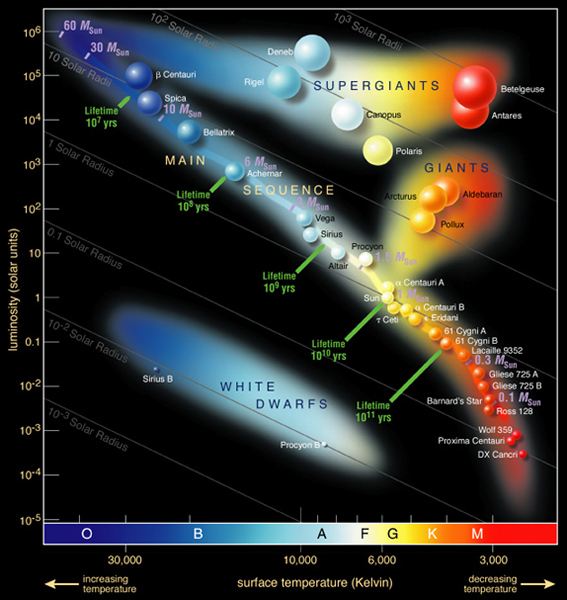

A star that is blue or blue-white in color, such as Spica at the upper left, has a high surface temperature. In contrast, a red-colored star (such as Antares and Betelgeuse at the upper right), has a lower surface temperature. Image of Hertzsprung-Russell diagram via ESO.

Most red-colored stars are invisible to the unaided eye because they’re small and faint red dwarf stars. Cool red dwarf stars are only a fraction the size and luminosity of our sun, but are thought to make up about 70% of the stars in our Milky Way galaxy. These red dwarfs are extremely long-living stars with an expected life span of about a trillion years (1,000,000 million years).

Red-colored stars that are visible to the naked eye are fairly rare. In fact, all the bright red stars that we see in the night sky with the unaided eye are either red giants (such as the star Aldebaran) or red supergiants (such as the stars Antares and Betelgeuse).

Red supergiant stars are remarkably rare, accounting for one of every million or so stars in our Milky Way galaxy. Approximately 10 red supergiant stars are visible to the unaided eye in a dark sky. The great size of these red supergiants makes these stars quite luminous, despite being rather distant. For example, Antares is thought to reside some 600 light-years away, but this star shines at 1st-magnitude brightness all the same.

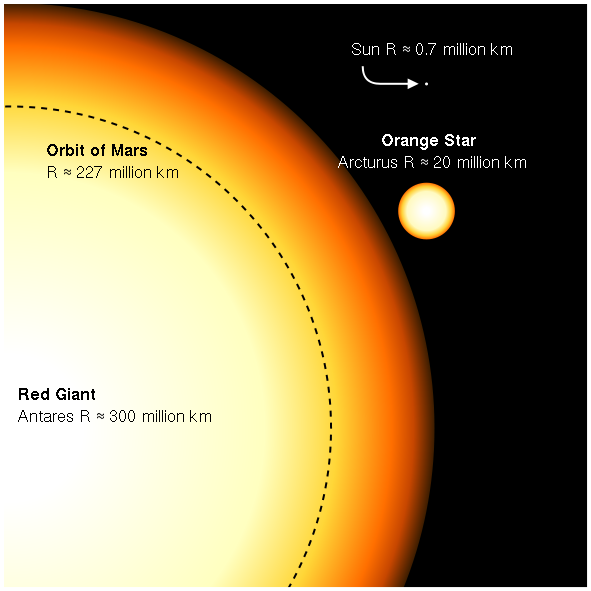

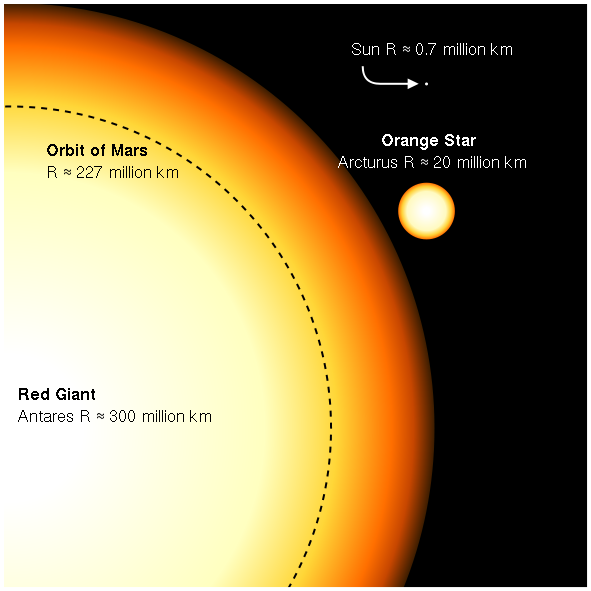

If Antares replaced the sun in our solar system, its circumference would extend beyond the orbit of the fourth planet, Mars. Here, Antares is shown in contrast to another star, Arcturus, and our sun. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

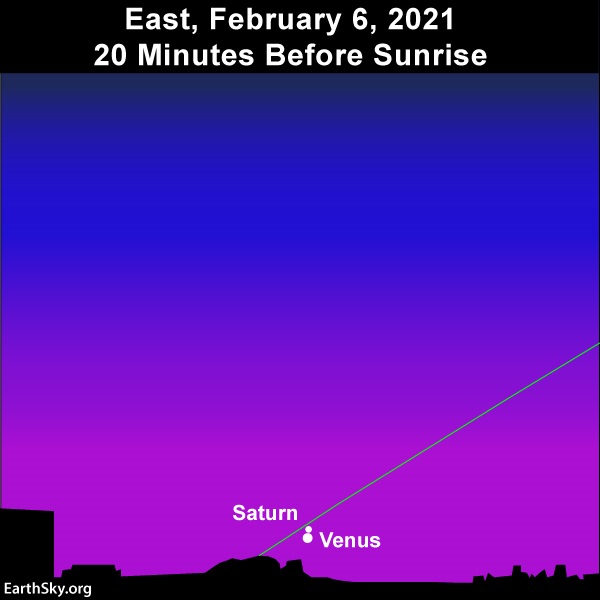

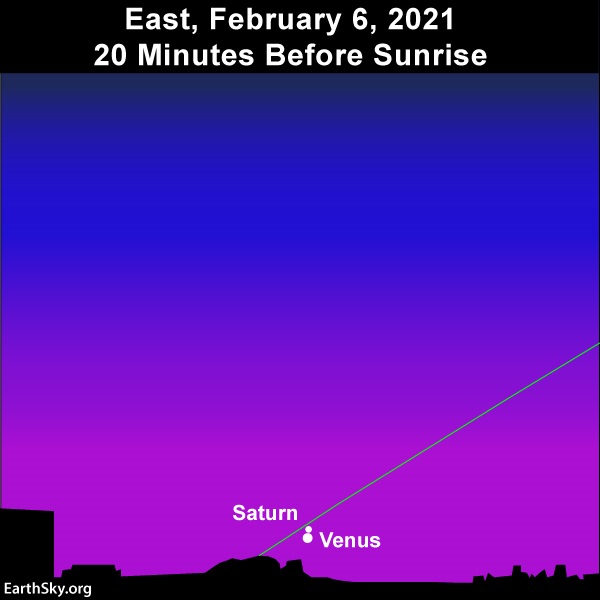

After Antares disappears into the brightening morning dawn, you might or might not catch the conjunction of planets Venus and Saturn sitting low in the sky in the glare of late morning twilight. You’ll probably need binoculars for any chance of catching these two worlds, but more especially Saturn. Venus ranks as the third-brightest celestial body to light up the heavens, after the sun and moon, and outshines Saturn by some 65 times. Keep in mind that this conjunction won’t be nearly as obvious in the real sky as it is on our sky charts. You might not be able to see it at all!

The shallow tilt of the ecliptic will make the Venus-Saturn conjunction hard to spot from northerly latitudes, even with binoculars.

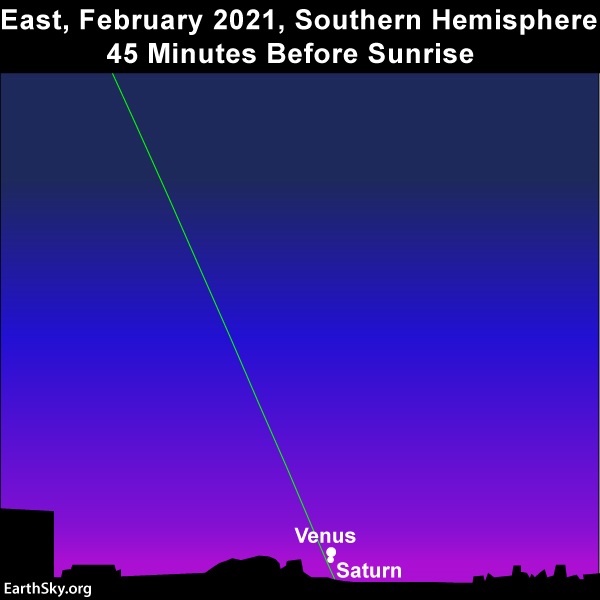

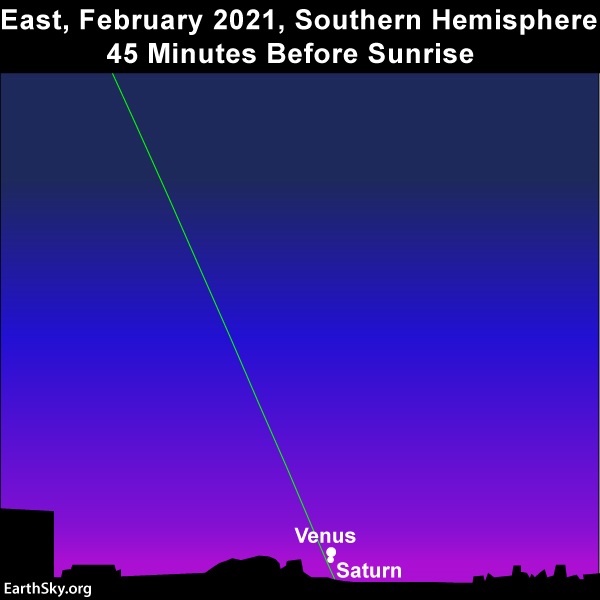

The steeper tilt of the ecliptic gives the Southern Hemisphere the advantage for catching the conjunction of Venus and Saturn before sunrise February 6, 2021.

Bottom line: Let the moon show you Antares, the red supergiant star, on the morning of February 6, 2021.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/36LtECg

Watch for the waning crescent moon to pair up with red Antares, the brightest star in the constellation Scorpius the Scorpion, on the morning of February 6, 2021. After that, you might try your luck at catching the Venus-Saturn conjunction – also February 6 – but in a bright morning twilight sky. Be aware that Antares and the moon will be easy to see, and Venus and Saturn will be hard to see, even with binoculars.

What’s more – after Antares has disappeared in the light of the coming sunrise – the lit side of the moon will still be visible, and it’ll still be pointing more or less toward the horizon, toward two other planets that you might or might not see, Jupiter and Saturn. They are both just now entering the morning sky, having dazzled us all with their Great Conjunction in the evening sky in December 2020. Jupiter is very bright, second only to Venus among the planets. Still, all of these planets are very near the sunrise glare. You might not see any of them.

Read more: Moon and morning planets February 8, 9 and 10

Read more: EarthSky’s February 2021 guide to the bright planets

Maybe you can’t see any of these planets right now. If not, be sure to get up early enough to see and contemplate mighty Antares near the moon. It’ll look like a pinpoint of light. But Antares is a huge red supergiant star, with some 15 to 18 times our sun’s mass. It’s a truly enormous star, with a radius in excess of three astronomical units, or three times Earth’s average distance from the sun. If, by some bit of magic, Antares were suddenly substituted for our sun, its surface would consume the Earth and extend well past the orbit of Mars!

Unlike red dwarf stars (discussed below), the lifespan of supergiant stars is short (by stellar standards). Antares is only about 12 million years old, and already well into the autumn of its years. That’s in contrast to our sun, which is 4.5 billion years old, and only middle-aged.

Notice the ruddy color of Antares. It indicates a low surface temperature of about 3,500 kelvins (5,800 degrees F or 3,200 C). That’s in contrast to a surface temperature of about 6,000 kelvins (10,000 F or 5,500 C) for our yellow-colored sun. Or contrast Antares to a very hot star, like blue-white Spica in the constellation Virgo the Maiden. Spica boasts a surface temperature of around 22,400 kelvins (39,900 F or 22,100 C).

A star that is blue or blue-white in color, such as Spica at the upper left, has a high surface temperature. In contrast, a red-colored star (such as Antares and Betelgeuse at the upper right), has a lower surface temperature. Image of Hertzsprung-Russell diagram via ESO.

Most red-colored stars are invisible to the unaided eye because they’re small and faint red dwarf stars. Cool red dwarf stars are only a fraction the size and luminosity of our sun, but are thought to make up about 70% of the stars in our Milky Way galaxy. These red dwarfs are extremely long-living stars with an expected life span of about a trillion years (1,000,000 million years).

Red-colored stars that are visible to the naked eye are fairly rare. In fact, all the bright red stars that we see in the night sky with the unaided eye are either red giants (such as the star Aldebaran) or red supergiants (such as the stars Antares and Betelgeuse).

Red supergiant stars are remarkably rare, accounting for one of every million or so stars in our Milky Way galaxy. Approximately 10 red supergiant stars are visible to the unaided eye in a dark sky. The great size of these red supergiants makes these stars quite luminous, despite being rather distant. For example, Antares is thought to reside some 600 light-years away, but this star shines at 1st-magnitude brightness all the same.

If Antares replaced the sun in our solar system, its circumference would extend beyond the orbit of the fourth planet, Mars. Here, Antares is shown in contrast to another star, Arcturus, and our sun. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

After Antares disappears into the brightening morning dawn, you might or might not catch the conjunction of planets Venus and Saturn sitting low in the sky in the glare of late morning twilight. You’ll probably need binoculars for any chance of catching these two worlds, but more especially Saturn. Venus ranks as the third-brightest celestial body to light up the heavens, after the sun and moon, and outshines Saturn by some 65 times. Keep in mind that this conjunction won’t be nearly as obvious in the real sky as it is on our sky charts. You might not be able to see it at all!

The shallow tilt of the ecliptic will make the Venus-Saturn conjunction hard to spot from northerly latitudes, even with binoculars.

The steeper tilt of the ecliptic gives the Southern Hemisphere the advantage for catching the conjunction of Venus and Saturn before sunrise February 6, 2021.

Bottom line: Let the moon show you Antares, the red supergiant star, on the morning of February 6, 2021.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/36LtECg

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire