Project Nightflight, a Vienna-based astrophotography group, caught Canopus over the island of La Palma in Spain’s Canary Islands. Read more about this image.

Sirius is the brightest star in the sky. It’s visible to all of us across the globe. The 2nd-brightest star, Canopus, is more challenging to spot because it’s located so far south in the sky.

For those in the Southern Hemisphere, no problem. Canopus is visible most of the year high in the sky.

But those in the far-northern part of the Northern Hemisphere might never get a peek. If you want to see Canopus in the Northern Hemisphere, head to southern latitudes in winter time, as many snowbirds do, and look south for a bright star close to the horizon.

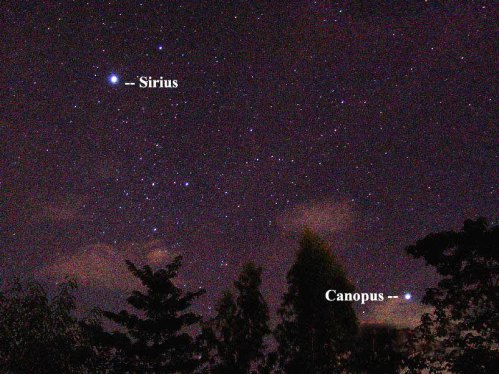

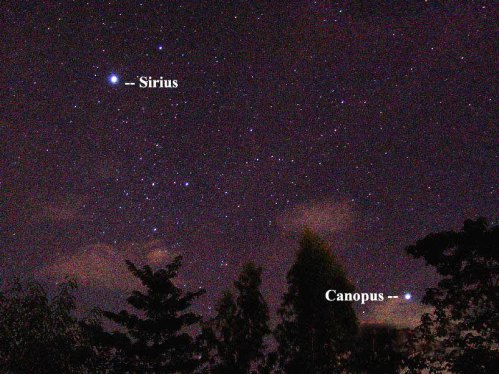

If you are far enough south on Earth’s globe, you can see the sky’s second-brightest star, Canopus, below the sky’s brightest star, Sirius. Photo taken by Jun Lao of the Philippines on December 29, 2005.

Look for Canopus below Sirius, the sky's brightest star.

Are you situated on Earth to be able to see Canopus? Will you see it? It depends on how far south you are, and what time of year you’re looking. Canopus never rises above the horizon for locations north of about 37 degrees north latitude. In the United States, that line runs from roughly Richmond, Virginia; westward to Bowling Green, Kentucky; through Trinidad, Colorado; and onward to San Jose, California – just south of San Francisco. You must be south of those places to see Canopus.

If you’re in the southern U.S., you’ll have no trouble finding Canopus on winter evenings. Just look to the south, below brilliant Sirius. February evenings are a perfect time to look, when Canopus is at its highest in the sky around 9 p.m.

Those who can see it from the Northern Hemisphere sometimes ask

What is that bright star below Sirius?

Fair question, because – from latitudes like those of the United States – Canopus appears in the southern sky almost directly south of Sirius, the brightest star of the nighttime sky. When Sirius is at its highest point to the south, Canopus is about 36 degrees below it.

At the end of December, Canopus stands at its highest point to the south after midnight. In January, it reaches that point at about 10 p.m. By the beginning of March, Canopus is due south at about 8 p.m., although the exact timing on all of these dates depends on the observer’s geographic location.

For observers in the Southern Hemisphere it is an entirely different story. From latitudes south of the equator, both Canopus and Sirius – the sky’s two brightest stars – appear high in the sky, and they often appear together. They are like twin beacons crossing the heavens. The sight of them is enough to make a northern observer envy the southern skies!

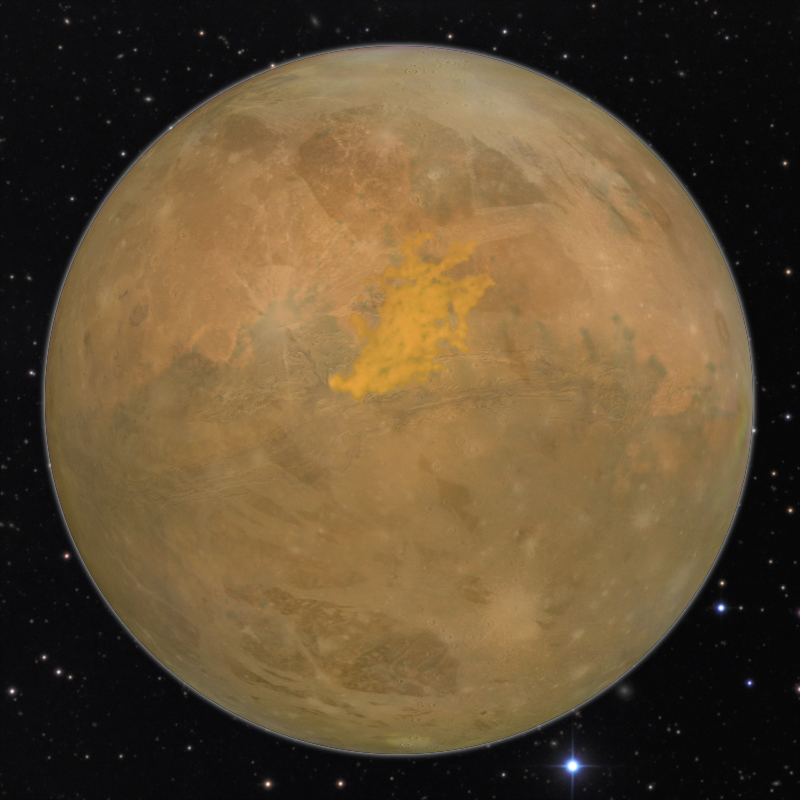

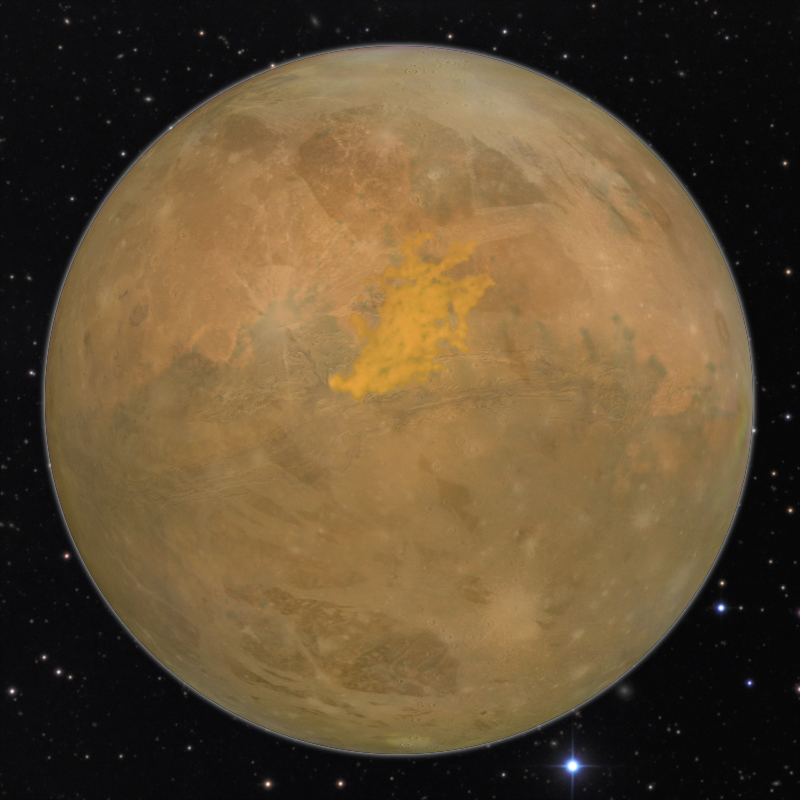

Artist’s concept of Arrakis, the third planet of Canopus in Frank Herbert’s science fiction novel “Dune.” Image via Wikipedia’s Stars and Planetary Systems in Fiction.

Canopus in science fiction. In Frank Herbert’s 1965 novel Dune and other novels in his Dune universe, the fictional planet Arrakis – a vast desert world, home to sandworms and Bedouin-like humans called the Fremen – is the third planet from a real star in our night sky. That star is Canopus – the second-brightest star visible in Earth’s sky – in what we know as the constellation Carina.

In Herbert’s novel, the desert planet Arrakis is the only source of “spice,” the most important and valuable substance in the Dune universe.

It’s possible, according to Wikipedia (which references the famous book Star Names: Their Lore and Meaning by Richard Allen), that Herbert was influenced in his choice of this star as the primary for Arrakis by a common etymological derivation of the name Canopus:

… as a Latinization (through Greek Kanobos) from the Coptic Kahi Nub (“Golden Earth”), which refers to how Canopus would have appeared over the southern desert horizon in ancient Egypt, reddened by atmospheric absorption.

Indeed, from much of the civilized world in ancient times, Canopus would have appeared low in the sky, when it was visible at all. And so, yes, its bright light would be reddened due to looking at it through a greater thickness of atmosphere in the direction toward the horizon – just as our sun or moon seen low in the sky looks redder than usual. Golden Earth indeed.

By the way, although Arrakis is fictional, Canopus is not only very real but also much hotter and larger than our sun. See the Science section below.

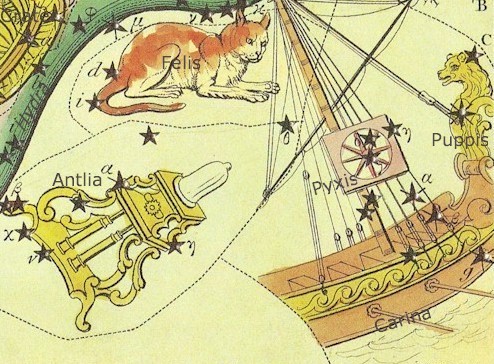

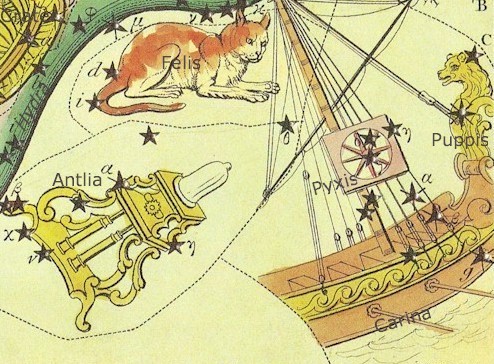

Drawing from Urania’s Mirror, 1825, showing Carina as part of the ancient ship Argo Navis. Via constellationofwords.com

History and mythology of Canopus. Canopus is also called Alpha Carinae, the brightest star in the constellation Carina the Keel. This constellation used to be considered part of Argo Navis, the ship of Jason and his famed Argonauts, as seen in our sky. Canopus originally marked a keel or rudder of this ancient celestial ship. Alas, the great Argo Navis constellation no longer exists. Modern imaginations see it as broken into three parts: the Keel (Carina, of which Canopus is part), sails (Vela) and the poop deck (Puppis).

For those far enough south to see it, Canopus was a star of great importance from ancient times to modern times as a primary navigational star. This is surely due to its brightness.

The origin of the name Canopus is subject to question. By some accounts it is the name of a ship’s captain from the Trojan War. Another theory is that it is from ancient Egyptian meaning Golden Earth, a possible reference to the star’s appearance as seen through atmospheric haze near the horizon from Egyptian latitudes.

Canopus is a supergiant of spectral type F and appears essentially white to the naked eye. Image via Fred Espenak/astropixels.com.

Canopus seen from the International Space Station (ISS).

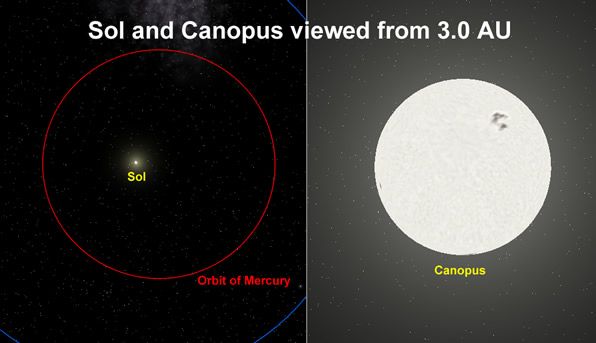

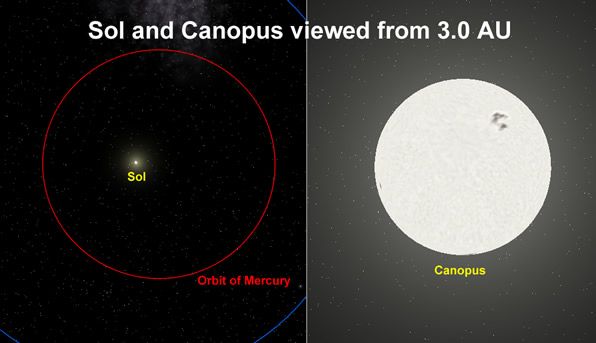

A comparison of the size of our sun to that of Canopus. Via dunenovels.com

Science of Canopus. According to data obtained by the Hipparcos Space Astrometry Mission, Canopus is about 313 light-years away. Spectroscopically, it is an F0 type star, making it significantly hotter than our sun (roughly 13,600 degrees F or 7538 C at its surface, compared to about 10,000 degrees F or 5538 C for the sun). Canopus also has a luminosity class rating of II, which makes it a “bright giant” star much larger than the sun. (Some classifications make it a type Ia “supergiant”.)

If they were placed side by side, it would take about 65 suns to fit across Canopus. Although Canopus appears significantly less bright than Sirius, it is really much brighter, blazing with the brilliance of 14,000 suns! With non-visible forms of light energy factored in, it surpasses the sun by more than 15,000 times.

Although its exact age is unknown, Canopus’ great mass dictates that this star must be near the end of its lifetime and is likely is a few million to a few tens of millions of years old. Compared to our sedate middle-aged five-billion-year-old sun, Canopus has lived in the stellar fast lane and is destined to die young.

Canopus’s position is RA: 6h 23m 57s, dec: -52° 41′ 45″

How can you be sure which star is Sirius? Orion’s Belt – three stars in a short, straight row (see top of this photo) – point to it. Here, you see Sirius, and, below it, the sky’s second-brightest star,Canopus. Photo via Ramalingam Rajaraman.

Enjoying EarthSky so far? Sign up for our free daily newsletter today!

Bottom line: Canopus is the second brightest star as seen from Earth. To see Canopus, you must either be in the Southern Hemisphere or in the southern latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere looking south during winter.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2GAt5zZ

Project Nightflight, a Vienna-based astrophotography group, caught Canopus over the island of La Palma in Spain’s Canary Islands. Read more about this image.

Sirius is the brightest star in the sky. It’s visible to all of us across the globe. The 2nd-brightest star, Canopus, is more challenging to spot because it’s located so far south in the sky.

For those in the Southern Hemisphere, no problem. Canopus is visible most of the year high in the sky.

But those in the far-northern part of the Northern Hemisphere might never get a peek. If you want to see Canopus in the Northern Hemisphere, head to southern latitudes in winter time, as many snowbirds do, and look south for a bright star close to the horizon.

If you are far enough south on Earth’s globe, you can see the sky’s second-brightest star, Canopus, below the sky’s brightest star, Sirius. Photo taken by Jun Lao of the Philippines on December 29, 2005.

Look for Canopus below Sirius, the sky's brightest star.

Are you situated on Earth to be able to see Canopus? Will you see it? It depends on how far south you are, and what time of year you’re looking. Canopus never rises above the horizon for locations north of about 37 degrees north latitude. In the United States, that line runs from roughly Richmond, Virginia; westward to Bowling Green, Kentucky; through Trinidad, Colorado; and onward to San Jose, California – just south of San Francisco. You must be south of those places to see Canopus.

If you’re in the southern U.S., you’ll have no trouble finding Canopus on winter evenings. Just look to the south, below brilliant Sirius. February evenings are a perfect time to look, when Canopus is at its highest in the sky around 9 p.m.

Those who can see it from the Northern Hemisphere sometimes ask

What is that bright star below Sirius?

Fair question, because – from latitudes like those of the United States – Canopus appears in the southern sky almost directly south of Sirius, the brightest star of the nighttime sky. When Sirius is at its highest point to the south, Canopus is about 36 degrees below it.

At the end of December, Canopus stands at its highest point to the south after midnight. In January, it reaches that point at about 10 p.m. By the beginning of March, Canopus is due south at about 8 p.m., although the exact timing on all of these dates depends on the observer’s geographic location.

For observers in the Southern Hemisphere it is an entirely different story. From latitudes south of the equator, both Canopus and Sirius – the sky’s two brightest stars – appear high in the sky, and they often appear together. They are like twin beacons crossing the heavens. The sight of them is enough to make a northern observer envy the southern skies!

Artist’s concept of Arrakis, the third planet of Canopus in Frank Herbert’s science fiction novel “Dune.” Image via Wikipedia’s Stars and Planetary Systems in Fiction.

Canopus in science fiction. In Frank Herbert’s 1965 novel Dune and other novels in his Dune universe, the fictional planet Arrakis – a vast desert world, home to sandworms and Bedouin-like humans called the Fremen – is the third planet from a real star in our night sky. That star is Canopus – the second-brightest star visible in Earth’s sky – in what we know as the constellation Carina.

In Herbert’s novel, the desert planet Arrakis is the only source of “spice,” the most important and valuable substance in the Dune universe.

It’s possible, according to Wikipedia (which references the famous book Star Names: Their Lore and Meaning by Richard Allen), that Herbert was influenced in his choice of this star as the primary for Arrakis by a common etymological derivation of the name Canopus:

… as a Latinization (through Greek Kanobos) from the Coptic Kahi Nub (“Golden Earth”), which refers to how Canopus would have appeared over the southern desert horizon in ancient Egypt, reddened by atmospheric absorption.

Indeed, from much of the civilized world in ancient times, Canopus would have appeared low in the sky, when it was visible at all. And so, yes, its bright light would be reddened due to looking at it through a greater thickness of atmosphere in the direction toward the horizon – just as our sun or moon seen low in the sky looks redder than usual. Golden Earth indeed.

By the way, although Arrakis is fictional, Canopus is not only very real but also much hotter and larger than our sun. See the Science section below.

Drawing from Urania’s Mirror, 1825, showing Carina as part of the ancient ship Argo Navis. Via constellationofwords.com

History and mythology of Canopus. Canopus is also called Alpha Carinae, the brightest star in the constellation Carina the Keel. This constellation used to be considered part of Argo Navis, the ship of Jason and his famed Argonauts, as seen in our sky. Canopus originally marked a keel or rudder of this ancient celestial ship. Alas, the great Argo Navis constellation no longer exists. Modern imaginations see it as broken into three parts: the Keel (Carina, of which Canopus is part), sails (Vela) and the poop deck (Puppis).

For those far enough south to see it, Canopus was a star of great importance from ancient times to modern times as a primary navigational star. This is surely due to its brightness.

The origin of the name Canopus is subject to question. By some accounts it is the name of a ship’s captain from the Trojan War. Another theory is that it is from ancient Egyptian meaning Golden Earth, a possible reference to the star’s appearance as seen through atmospheric haze near the horizon from Egyptian latitudes.

Canopus is a supergiant of spectral type F and appears essentially white to the naked eye. Image via Fred Espenak/astropixels.com.

Canopus seen from the International Space Station (ISS).

A comparison of the size of our sun to that of Canopus. Via dunenovels.com

Science of Canopus. According to data obtained by the Hipparcos Space Astrometry Mission, Canopus is about 313 light-years away. Spectroscopically, it is an F0 type star, making it significantly hotter than our sun (roughly 13,600 degrees F or 7538 C at its surface, compared to about 10,000 degrees F or 5538 C for the sun). Canopus also has a luminosity class rating of II, which makes it a “bright giant” star much larger than the sun. (Some classifications make it a type Ia “supergiant”.)

If they were placed side by side, it would take about 65 suns to fit across Canopus. Although Canopus appears significantly less bright than Sirius, it is really much brighter, blazing with the brilliance of 14,000 suns! With non-visible forms of light energy factored in, it surpasses the sun by more than 15,000 times.

Although its exact age is unknown, Canopus’ great mass dictates that this star must be near the end of its lifetime and is likely is a few million to a few tens of millions of years old. Compared to our sedate middle-aged five-billion-year-old sun, Canopus has lived in the stellar fast lane and is destined to die young.

Canopus’s position is RA: 6h 23m 57s, dec: -52° 41′ 45″

How can you be sure which star is Sirius? Orion’s Belt – three stars in a short, straight row (see top of this photo) – point to it. Here, you see Sirius, and, below it, the sky’s second-brightest star,Canopus. Photo via Ramalingam Rajaraman.

Enjoying EarthSky so far? Sign up for our free daily newsletter today!

Bottom line: Canopus is the second brightest star as seen from Earth. To see Canopus, you must either be in the Southern Hemisphere or in the southern latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere looking south during winter.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2GAt5zZ

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire