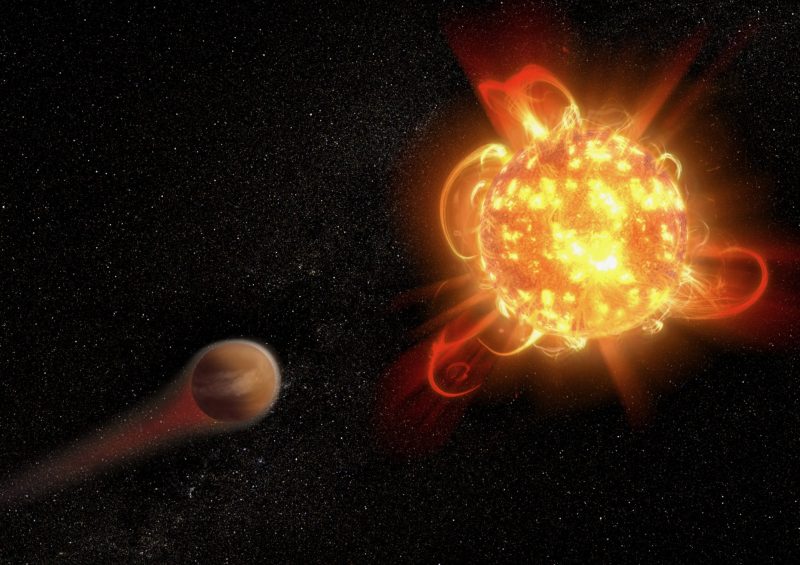

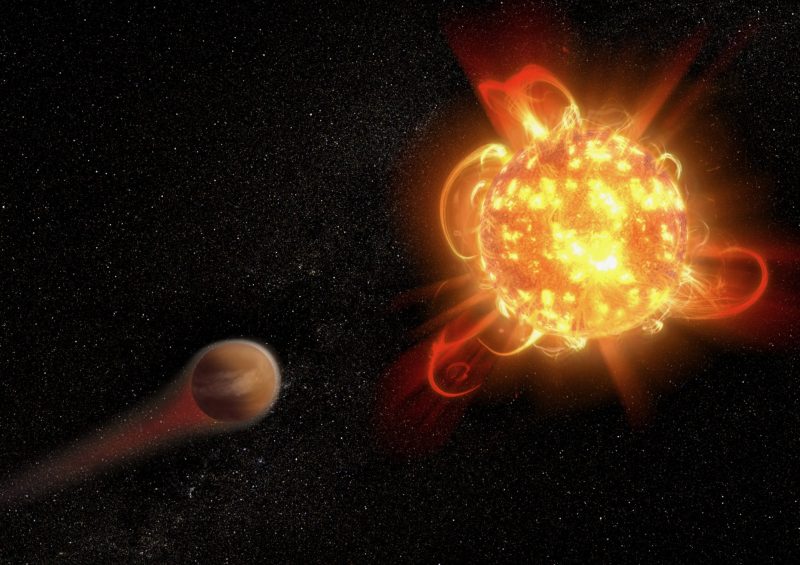

Artist’s concept of a distant red dwarf star and accompanying exoplanet. Red dwarfs are common in our galaxy. They produce volatile, deadly flares – and accompanying space weather – that can erode the atmospheres of any nearby planets and severely endanger any existing life. But … maybe not always, according to a new study. Image via NASA/ ESA/ D. Player (STScI).

A few days ago, we reported new findings about how space weather in the vicinity of Proxima Centauri, the nearest star to our sun, might inhibit life on Proxima’s planets. Space weather stems from powerful radiation from flares on volatile red dwarf (or M dwarf) stars like Proxima. There are a lot of these stars in our galaxy, and it’s been with some wistfulness that astronomers in recent years have reported on how red dwarf flares can lead to space weather, decreasing the chance of exoplanet life. But science marches on, and now there’s a newly-announced study, from researchers at Northwestern University, that provides some hope for those searching for life. The study suggests that space weather might not always be fatal to life. Hostile space weather might even help astronomers detect life on exoplanets around red dwarfs or other stars.

The researchers published the new peer-reviewed findings in Nature Astronomy on December 21, 2020.

It is known that intense solar flares from red dwarfs or other active stars can erode or even strip the atmospheres from planets that orbit too close. In the case of red dwarfs, these stars are cooler and smaller than the sun, which means such planets are often in the habitable zone, where temperatures are suitable for liquid water on their surfaces. But, they orbit very close to their stars, so they are pummelled by intense radiation. So how could it be that this space weather is not always as bad for life as it is assumed to be?

EarthSky 2021 lunar calendars now available! Order now. Going fast!

It all comes down to chemistry. In the new study, the researchers found that such flares play a significant role in the development of a planet’s atmosphere. Howard Chen, first author of the study, said in a statement:

We compared the atmospheric chemistry of planets experiencing frequent flares with planets experiencing no flares. The long-term atmospheric chemistry is very different.

The senior author of the study, Daniel Horton, added:

We’ve found that stellar flares might not preclude the existence of life. In some cases, flaring doesn’t erode all of the atmospheric ozone. Surface life might still have a fighting chance.

That’s good news for the possibility of life on at least some otherwise potentially habitable worlds orbiting red dwarf stars.

As Horton further explained:

We studied planets orbiting within the habitable zones of M and K dwarf stars, the most common stars in the universe. Habitable zones around these stars are narrower because the stars are smaller and less powerful than stars like our sun. On the flip side, M and K dwarf stars are thought to have more frequent flaring activity than our sun, and their tidally locked planets are unlikely to have magnetic fields helping deflect their stellar winds.

Daniel Horton at Northwestern University, senior author of the new paper. Image via Northwestern University.

The study found that it might be easier in some cases for life to survive around red dwarfs than previously thought, but it, and previous studies, also showed that hostile space weather might even make it easier to detect such life. How?

If there were gases in a planet’s atmosphere that were a sign of life – such as nitrogen dioxide, nitrous oxide or nitric acid – stellar flares could actually increase their abundance. If such gases were at a very low level and difficult to detect from Earth, flares could increase their amounts to levels that were detectable. It’s an intriguing and ironic possibility, that the same space weather that could extinguish life on a planet might also aid astronomers in detecting life. As Chen explained:

Space weather events are typically viewed as a detriment to habitability. But our study quantitatively showed that some space weather can actually help us detect signatures of important gases that might signify biological processes.

Chen and his colleagues had also incorporated stellar flare data from NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Satellite Survey (TESS) mission, launched in 2018, into their model simulations. This helps researchers better understand the overall effects of space weather on exoplanet atmospheres.

Red dwarf stars are more active than our sun, frequently releasing deadly flares that could erode the atmospheres of planets that orbit too close. The sun has flares, too, of course, but in the case of Earth, our planet’s magnetic field protects us from them. While they might cause problems with power or communications systems, including satellites, they don’t endanger life itself on Earth’s surface. As Allison Youngblood, an astronomer at the University of Colorado Boulder and co-author of the study, described it:

Our sun is more of a gentle giant. It’s older and not as active as younger and smaller stars. Earth also has a strong magnetic field, which deflects the sun’s damaging winds.

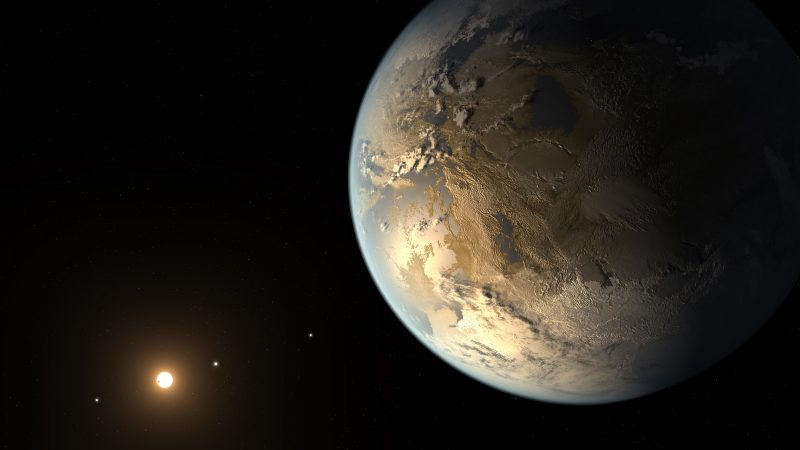

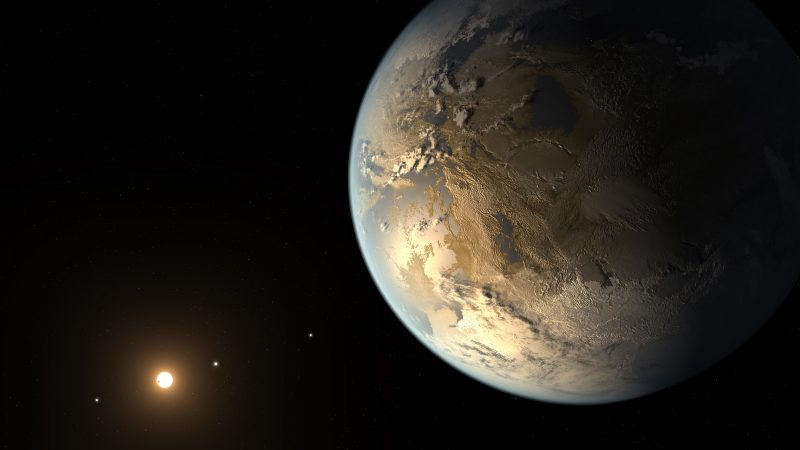

Artist’s concept of Kepler-186f, a potentially habitable exoplanet that orbits a red dwarf star 500 light-years from Earth. Unlike some other planets found around red dwarfs, it orbits a bit farther out, in the outer edge region of the star’s habitable zone, and may not be as affected by solar flares. Image via NASA/ NASA Ames/ SETI Institute/ JPL-Caltech.

The findings illustrate just how complex the possibility of alien life can be, that it’s not always as straightforward as we might think. It’s not just whether or not a planet is in the habitable zone of a star, for example, but rather there are many factors to consider relating to conditions both on the planet itself as well as its host star. The search for extraterrestrial life requires input from a wide range of scientific disciplines. As Eric T. Wolf, a planetary scientist at the University of Colorado Boulder and a co-author of the study, summed it up:

This project was a result of fantastic collective team effort. Our work highlights the benefits of interdisciplinary efforts when investigating conditions on extrasolar planets.

Bottom line: New research shows that solar flares – space weather – might not always be as dangerous for life on exoplanets as typically thought. It might even help astronomers discover alien life on distant worlds.

Source: Persistence of flare-driven atmospheric chemistry on rocky habitable zone worlds

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/3hNjQvM

Artist’s concept of a distant red dwarf star and accompanying exoplanet. Red dwarfs are common in our galaxy. They produce volatile, deadly flares – and accompanying space weather – that can erode the atmospheres of any nearby planets and severely endanger any existing life. But … maybe not always, according to a new study. Image via NASA/ ESA/ D. Player (STScI).

A few days ago, we reported new findings about how space weather in the vicinity of Proxima Centauri, the nearest star to our sun, might inhibit life on Proxima’s planets. Space weather stems from powerful radiation from flares on volatile red dwarf (or M dwarf) stars like Proxima. There are a lot of these stars in our galaxy, and it’s been with some wistfulness that astronomers in recent years have reported on how red dwarf flares can lead to space weather, decreasing the chance of exoplanet life. But science marches on, and now there’s a newly-announced study, from researchers at Northwestern University, that provides some hope for those searching for life. The study suggests that space weather might not always be fatal to life. Hostile space weather might even help astronomers detect life on exoplanets around red dwarfs or other stars.

The researchers published the new peer-reviewed findings in Nature Astronomy on December 21, 2020.

It is known that intense solar flares from red dwarfs or other active stars can erode or even strip the atmospheres from planets that orbit too close. In the case of red dwarfs, these stars are cooler and smaller than the sun, which means such planets are often in the habitable zone, where temperatures are suitable for liquid water on their surfaces. But, they orbit very close to their stars, so they are pummelled by intense radiation. So how could it be that this space weather is not always as bad for life as it is assumed to be?

EarthSky 2021 lunar calendars now available! Order now. Going fast!

It all comes down to chemistry. In the new study, the researchers found that such flares play a significant role in the development of a planet’s atmosphere. Howard Chen, first author of the study, said in a statement:

We compared the atmospheric chemistry of planets experiencing frequent flares with planets experiencing no flares. The long-term atmospheric chemistry is very different.

The senior author of the study, Daniel Horton, added:

We’ve found that stellar flares might not preclude the existence of life. In some cases, flaring doesn’t erode all of the atmospheric ozone. Surface life might still have a fighting chance.

That’s good news for the possibility of life on at least some otherwise potentially habitable worlds orbiting red dwarf stars.

As Horton further explained:

We studied planets orbiting within the habitable zones of M and K dwarf stars, the most common stars in the universe. Habitable zones around these stars are narrower because the stars are smaller and less powerful than stars like our sun. On the flip side, M and K dwarf stars are thought to have more frequent flaring activity than our sun, and their tidally locked planets are unlikely to have magnetic fields helping deflect their stellar winds.

Daniel Horton at Northwestern University, senior author of the new paper. Image via Northwestern University.

The study found that it might be easier in some cases for life to survive around red dwarfs than previously thought, but it, and previous studies, also showed that hostile space weather might even make it easier to detect such life. How?

If there were gases in a planet’s atmosphere that were a sign of life – such as nitrogen dioxide, nitrous oxide or nitric acid – stellar flares could actually increase their abundance. If such gases were at a very low level and difficult to detect from Earth, flares could increase their amounts to levels that were detectable. It’s an intriguing and ironic possibility, that the same space weather that could extinguish life on a planet might also aid astronomers in detecting life. As Chen explained:

Space weather events are typically viewed as a detriment to habitability. But our study quantitatively showed that some space weather can actually help us detect signatures of important gases that might signify biological processes.

Chen and his colleagues had also incorporated stellar flare data from NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Satellite Survey (TESS) mission, launched in 2018, into their model simulations. This helps researchers better understand the overall effects of space weather on exoplanet atmospheres.

Red dwarf stars are more active than our sun, frequently releasing deadly flares that could erode the atmospheres of planets that orbit too close. The sun has flares, too, of course, but in the case of Earth, our planet’s magnetic field protects us from them. While they might cause problems with power or communications systems, including satellites, they don’t endanger life itself on Earth’s surface. As Allison Youngblood, an astronomer at the University of Colorado Boulder and co-author of the study, described it:

Our sun is more of a gentle giant. It’s older and not as active as younger and smaller stars. Earth also has a strong magnetic field, which deflects the sun’s damaging winds.

Artist’s concept of Kepler-186f, a potentially habitable exoplanet that orbits a red dwarf star 500 light-years from Earth. Unlike some other planets found around red dwarfs, it orbits a bit farther out, in the outer edge region of the star’s habitable zone, and may not be as affected by solar flares. Image via NASA/ NASA Ames/ SETI Institute/ JPL-Caltech.

The findings illustrate just how complex the possibility of alien life can be, that it’s not always as straightforward as we might think. It’s not just whether or not a planet is in the habitable zone of a star, for example, but rather there are many factors to consider relating to conditions both on the planet itself as well as its host star. The search for extraterrestrial life requires input from a wide range of scientific disciplines. As Eric T. Wolf, a planetary scientist at the University of Colorado Boulder and a co-author of the study, summed it up:

This project was a result of fantastic collective team effort. Our work highlights the benefits of interdisciplinary efforts when investigating conditions on extrasolar planets.

Bottom line: New research shows that solar flares – space weather – might not always be as dangerous for life on exoplanets as typically thought. It might even help astronomers discover alien life on distant worlds.

Source: Persistence of flare-driven atmospheric chemistry on rocky habitable zone worlds

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/3hNjQvM

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire