Image via CNT News.

The date of a new year is a human-made creation, not precisely fixed by any natural or seasonal marker. Our celebration of New Year’s Day on January 1 is a civil event, despite the fact that for us in the Northern Hemisphere – where daylight has ebbed to almost its lowest point and the days are starting to get longer again – there’s a feeling of rebirth in the air, a time of renewal. Hence why New Year’s resolutions are so popular.

So where does the New Year’s Day concept come from?

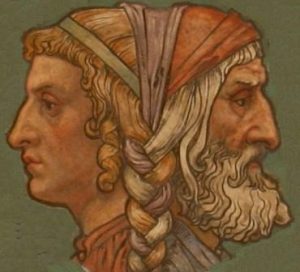

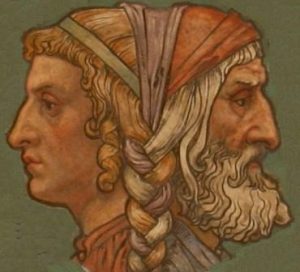

It stems from an ancient Roman custom, the feast of the Roman god Janus, who was the god of beginnings, gates, transitions, time, duality, doorways, passages, frames, and endings. This is also where the name for the month of January comes from, since Janus was depicted as having two faces. One face looked back into the past, and the other peered forward to the future, just like how on January 1, we can look back at the year that just ended, and look forward to the new year that lies ahead. There was no equivalent of Janus in Greek mythology.

To celebrate the new year, the Romans made promises to Janus. This is where the tradition of making New Year’s Day resolutions comes from. On that day it was customary to exchange cheerful words of good wishes. Shortly afterwards, on January 9, the rex sacrorum offered the sacrifice of a ram to Janus.

The ancient Roman god Janus. Image via tablesbeyondbelief.

Today, although many do celebrate New Year’s Day on January 1, some cultures and religions do not.

For example, Jews use a lunar calendar and celebrate the New Year in the fall on Rosh Hashanah, the first day of the month of Tishri, which is the seventh month of the Jewish year. This date usually occurs in September. Similar to other cultures’ New Year’s Day, the two-day holiday is both a time of rejoicing and of serious introspection, a time to celebrate the completion of another year while also taking stock of one’s life and looking ahead.

Learn more about Rosh Hashanah.

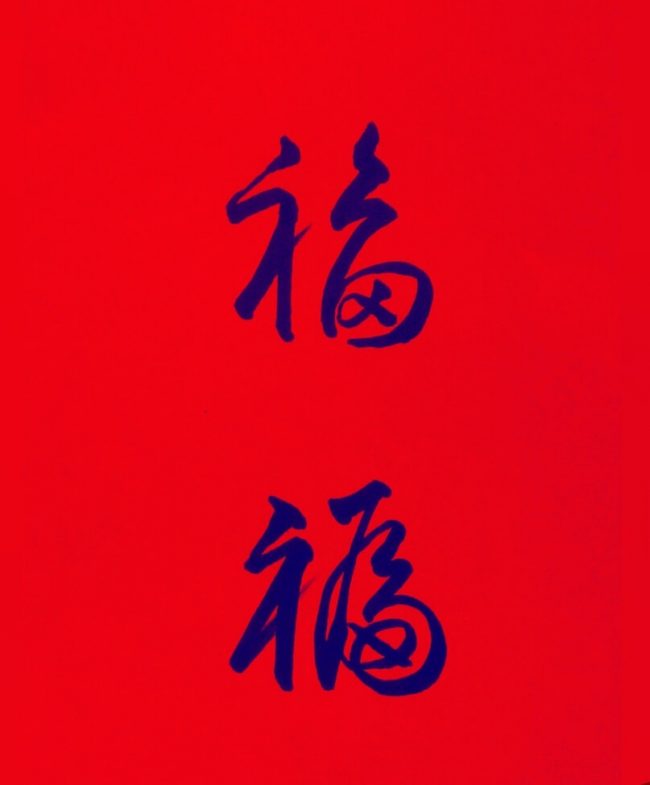

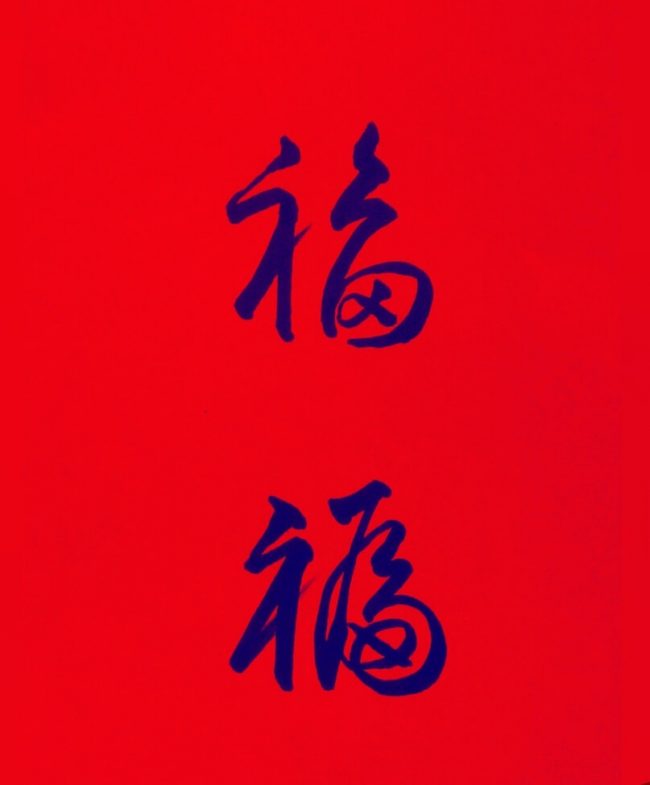

There is also the famous Chinese New Year, also known as the Lunar New Year, celebrated for weeks in January or early February. The Chinese New Year is the most important of Chinese holidays. Countries in Southeast Asia celebrate it including China, Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines. It’s also celebrated in Chinatowns and Asian homes around the world, and is considered a time to honor deities and ancestors and to be with family. The event always sparks a rush of travel that the New York Times has called the world’s largest annual human migration.

For 2020, the Chinese New Year was the Year of the Rat on the Chinese zodiac, which began on January 25. 2021 will be the Year of the Ox. The Chinese New Year will start on February 12th, and it will last until January 31st of 2022. Previous years of the ox were 1913, 1925, 1937, 1949, 1961, 1973, 1985, 1997, and 2009.

Learn more about the Chinese New Year.

Challah, a traditional round Jewish bread, eaten for Rosh Hashanah. Image via My Jewish Learning.

Our friend Matthew Chin in Hong Kong created this graphic and wrote: “The two Chinese characters are the same. It means ‘blessing,’ a hope that other people will get good luck. It is commonly used during Lunar New Year. The red background is also a kind of ‘good’ as Chinese people use red to represent ‘good luck.’” Thank you, Matthew!

For 2021, the Chinese New Year will be the Year of the Ox. Image via thechinesezodiac.org.

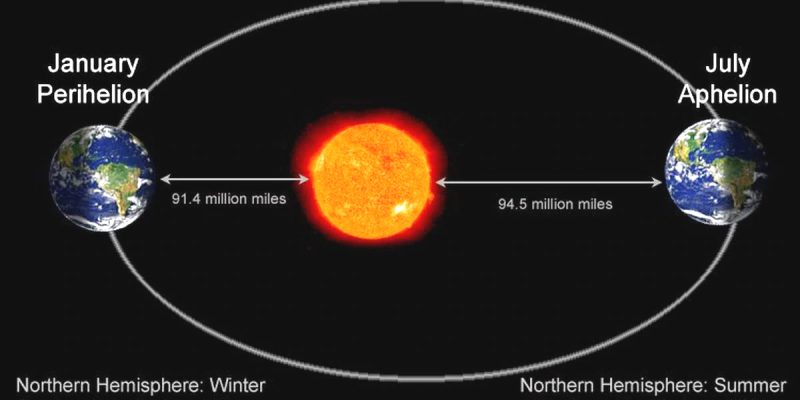

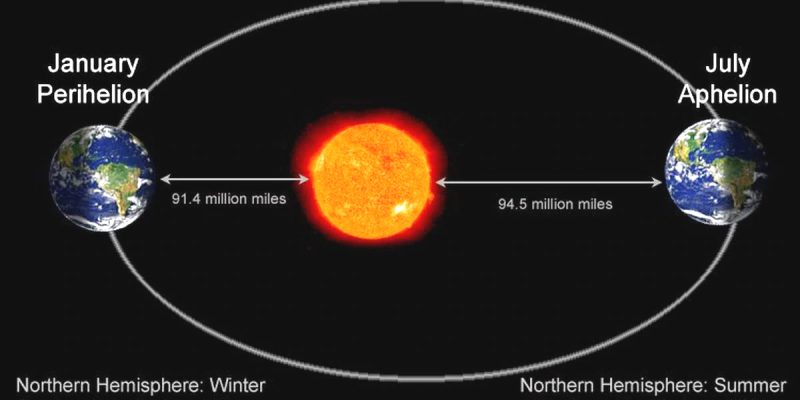

By the way, in addition to the longer days here in the Northern Hemisphere, there’s another astronomical occurrence around January 1 each year that’s also related to Earth’s year, as defined by our orbit around the sun. That is, Earth’s perihelion – or closest point to the sun – happens every year in early January.

January 1 hasn’t always been New Year’s Day throughout history, though.

In the past, some New Year’s celebrations took place at an equinox, a day when the sun is above Earth’s equator, and night and day are equal in length. In many cultures, the March or vernal equinox marks a time of transition and new beginnings, and so cultural celebrations of a new year were natural for that equinox. The September or autumnal equinox also had its proponents for the beginning of a new year. For example, the French Republican Calendar – implemented during the French Revolution and used for about 12 years from late 1793 to 1805 – started its year at the September equinox.

We don’t celebrate New Year’s Day on January 1 for this reason, but it would make sense if we did. Perihelion – our closest point to the sun in our yearly orbit – takes place each year in early January. Aphelion is when the Earth is farthest from the sun. Image via Corey S. Powell/ Twitter.

The Greeks celebrated the new year on the winter solstice, the shortest day of the year.

Bottom line: The reason to celebrate New Year’s Day on January 1 is historical, not astronomical. The New Year was celebrated according to astronomical events – such as equinoxes and solstices – eons ago. Our modern New Year’s Day celebration stems from the ancient, two-faced Roman god Janus, after whom the month of January is also named. One face of Janus looked back into the past, and the other peered forward to the future.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/35glNci

Image via CNT News.

The date of a new year is a human-made creation, not precisely fixed by any natural or seasonal marker. Our celebration of New Year’s Day on January 1 is a civil event, despite the fact that for us in the Northern Hemisphere – where daylight has ebbed to almost its lowest point and the days are starting to get longer again – there’s a feeling of rebirth in the air, a time of renewal. Hence why New Year’s resolutions are so popular.

So where does the New Year’s Day concept come from?

It stems from an ancient Roman custom, the feast of the Roman god Janus, who was the god of beginnings, gates, transitions, time, duality, doorways, passages, frames, and endings. This is also where the name for the month of January comes from, since Janus was depicted as having two faces. One face looked back into the past, and the other peered forward to the future, just like how on January 1, we can look back at the year that just ended, and look forward to the new year that lies ahead. There was no equivalent of Janus in Greek mythology.

To celebrate the new year, the Romans made promises to Janus. This is where the tradition of making New Year’s Day resolutions comes from. On that day it was customary to exchange cheerful words of good wishes. Shortly afterwards, on January 9, the rex sacrorum offered the sacrifice of a ram to Janus.

The ancient Roman god Janus. Image via tablesbeyondbelief.

Today, although many do celebrate New Year’s Day on January 1, some cultures and religions do not.

For example, Jews use a lunar calendar and celebrate the New Year in the fall on Rosh Hashanah, the first day of the month of Tishri, which is the seventh month of the Jewish year. This date usually occurs in September. Similar to other cultures’ New Year’s Day, the two-day holiday is both a time of rejoicing and of serious introspection, a time to celebrate the completion of another year while also taking stock of one’s life and looking ahead.

Learn more about Rosh Hashanah.

There is also the famous Chinese New Year, also known as the Lunar New Year, celebrated for weeks in January or early February. The Chinese New Year is the most important of Chinese holidays. Countries in Southeast Asia celebrate it including China, Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines. It’s also celebrated in Chinatowns and Asian homes around the world, and is considered a time to honor deities and ancestors and to be with family. The event always sparks a rush of travel that the New York Times has called the world’s largest annual human migration.

For 2020, the Chinese New Year was the Year of the Rat on the Chinese zodiac, which began on January 25. 2021 will be the Year of the Ox. The Chinese New Year will start on February 12th, and it will last until January 31st of 2022. Previous years of the ox were 1913, 1925, 1937, 1949, 1961, 1973, 1985, 1997, and 2009.

Learn more about the Chinese New Year.

Challah, a traditional round Jewish bread, eaten for Rosh Hashanah. Image via My Jewish Learning.

Our friend Matthew Chin in Hong Kong created this graphic and wrote: “The two Chinese characters are the same. It means ‘blessing,’ a hope that other people will get good luck. It is commonly used during Lunar New Year. The red background is also a kind of ‘good’ as Chinese people use red to represent ‘good luck.’” Thank you, Matthew!

For 2021, the Chinese New Year will be the Year of the Ox. Image via thechinesezodiac.org.

By the way, in addition to the longer days here in the Northern Hemisphere, there’s another astronomical occurrence around January 1 each year that’s also related to Earth’s year, as defined by our orbit around the sun. That is, Earth’s perihelion – or closest point to the sun – happens every year in early January.

January 1 hasn’t always been New Year’s Day throughout history, though.

In the past, some New Year’s celebrations took place at an equinox, a day when the sun is above Earth’s equator, and night and day are equal in length. In many cultures, the March or vernal equinox marks a time of transition and new beginnings, and so cultural celebrations of a new year were natural for that equinox. The September or autumnal equinox also had its proponents for the beginning of a new year. For example, the French Republican Calendar – implemented during the French Revolution and used for about 12 years from late 1793 to 1805 – started its year at the September equinox.

We don’t celebrate New Year’s Day on January 1 for this reason, but it would make sense if we did. Perihelion – our closest point to the sun in our yearly orbit – takes place each year in early January. Aphelion is when the Earth is farthest from the sun. Image via Corey S. Powell/ Twitter.

The Greeks celebrated the new year on the winter solstice, the shortest day of the year.

Bottom line: The reason to celebrate New Year’s Day on January 1 is historical, not astronomical. The New Year was celebrated according to astronomical events – such as equinoxes and solstices – eons ago. Our modern New Year’s Day celebration stems from the ancient, two-faced Roman god Janus, after whom the month of January is also named. One face of Janus looked back into the past, and the other peered forward to the future.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/35glNci

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire