Artist’s concept of huge flares on Proxima Centauri, which unleash ionizing radiation. This radiation could be dangerous for any possible life on planets orbiting close to the star. Image via NASA/ ESA/ G. Bacon (STScI)/ Phys.org.

This month, even as some astronomers are talking about a possible mystery radio signal from Proxima Centauri – a signal of interest to astronomers who search for intelligent life beyond Earth – other astronomers are talking about space weather in the vicinity of this star, which is the nearest star to our sun. Space weather in Proxima’s vicinity, they are saying, might make life on its planets difficult or even impossible.

What is space weather?

When we hear about weather, we might think of Earth – sun, clouds, rain, wind and so on – or we might think about conditions on other planets or moons that have atmospheres. Space weather isn’t about that. It’s a sort of “weather” that originates in stars, including our own sun, and that permeates the space near a star. Space weather consists of ionizing radiation released during flares on the sun or other stars. The radiation can be deadly for any life forms that may exist on distant planets. That’s especially true, astronomers say, for red dwarf stars, which have more frequent flares than our sun. Red dwarf stars can be very volatile. Proxima Centauri is a red dwarf star.

EarthSky lunar calendars are back in stock! We’re guaranteed to sell out – get one while you can!

Astronomers at the University of Sydney in Australia announced the new study on December 10, 2020. These researchers used radio waves to detect and probe the space weather in Proxima’s vicinity. Our sun’s nearest neighbor at only 4.2 light-years away, Proxima is known to have at least two planets orbiting it. One, Proxima Centauri b, is almost the same mass as Earth and the other, Proxima Centauri c, is about seven times more massive. Proxima Centauri b also orbits within its star’s habitable zone, where temperatures might allow liquid water to exist on planet’s surface. Sounds promising, right? But the new findings about flares on stars like Proxima suggest a grim prospect for life on the planets in this system.

The researchers published their peer-reviewed findings in The Astronomical Journal on December 9, 2020.

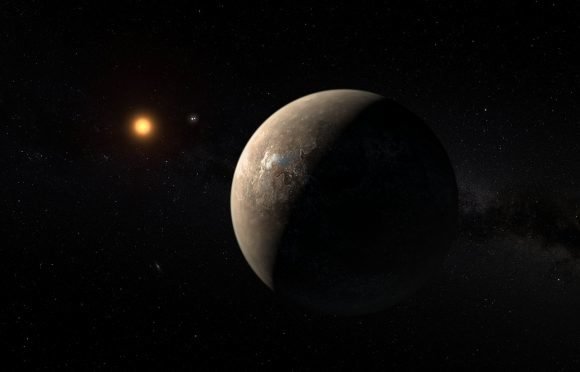

Hubble Space Telescope image of Proxima Centauri, the closest known star to the sun. Read more about this image. Image via ESA/ Hubble/ NASA.

These astronomers worked with CSIRO’s Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder (ASKAP) telescope in Western Australia and the Zadko Telescope at the University of Western Australia, as well as other instruments. Tara Murphy of the University of Sydney helped lead the study.

The new observations corroborate previous studies, showing that the planet known as Proxima Centauri b is subject to intense outbursts of ionizing radiation from its star. Proxima Centauri b is close to the star Proxima Centauri, as Andrew Zic, lead author of the study, explained:

But given Proxima Centauri is a cool, small red-dwarf star, it means this habitable zone is very close to the star; much closer in than Mercury is to our sun. What our research shows is that this makes the planets very vulnerable to dangerous ionizing radiation that could effectively sterilize the planets.

Our sun also emits deadly radiation during its occasional coronal mass ejections. Luckily, Earth is relatively far from our star, in contrast to Proxima’s planets; this radiation doesn’t affect us as powerfully. Plus, Earth has an atmosphere and magnetic field that also help to protect us. Zic commented:

Our own sun regularly emits hot clouds of ionized particles during what we call ‘coronal mass ejections.’ But given the sun is much hotter than Proxima Centauri and other red-dwarf stars, our ‘habitable zone’ is far from the sun’s surface, meaning the Earth is a relatively long way from these events.

Further, the Earth has a very powerful planetary magnetic field that shields us from these intense blasts of solar plasma.

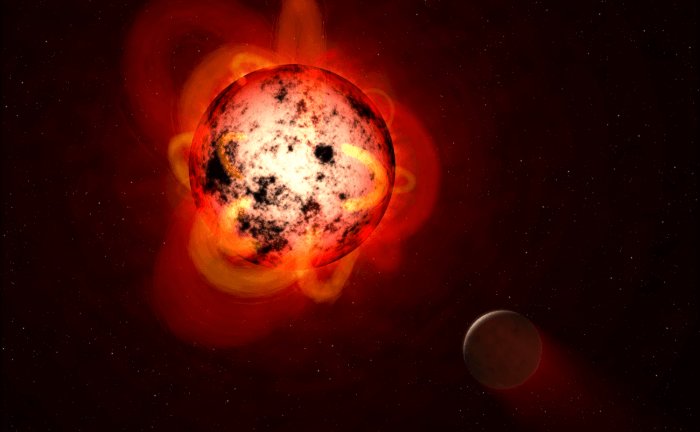

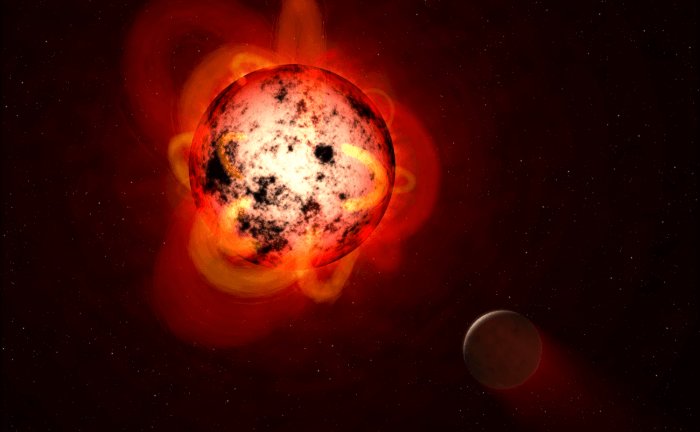

Artist’s concept of Proxima Centauri b, which is about 1.3 times the mass of Earth and orbits within the star’s habitable zone where liquid water could exist. The new data support previous studies, showing that the planet is subjected to intense radiation bursts from its star, putting its potential habitability in doubt. Image via ESO/ M. Kornmesser/ Phys.org.

The new study is the first that definitively links optical flares and radio bursts on a star other than the sun. This means that scientists can now use radio waves to study space weather around distant stars, which will provide important clues as to the potential habitability of any rocky planets orbiting them.

The success of these observations is exciting for astronomers. Tara Murphy at the University of Sydney reflected this in her comments:

This is an exciting result from ASKAP. The incredible data quality allowed us to view the stellar flare from Proxima Centauri over its full evolution in amazing detail.

Most importantly, we can see polarized light, which is a signature of these events. It’s a bit like looking at the star with sunglasses on. Once ASKAP is operating in full survey mode we should be able to observe many more events on nearby stars.

The ASKAP observations were also backed up by NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) and the Zadko Telescope.

Although there could be other explanations, the radio bursts from Proxima Centauri are thought to be connected to coronal mass ejections on the star, just like with our own sun. Zic said:

M-dwarf radio bursts might happen for different reasons than on the sun, where they are usually associated with coronal mass ejections. But it’s highly likely that there are similar events associated with the stellar flares and radio bursts we have seen in this study.

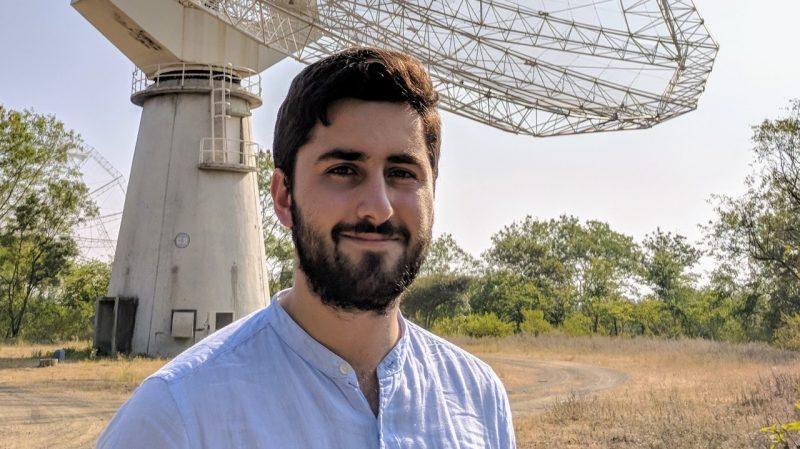

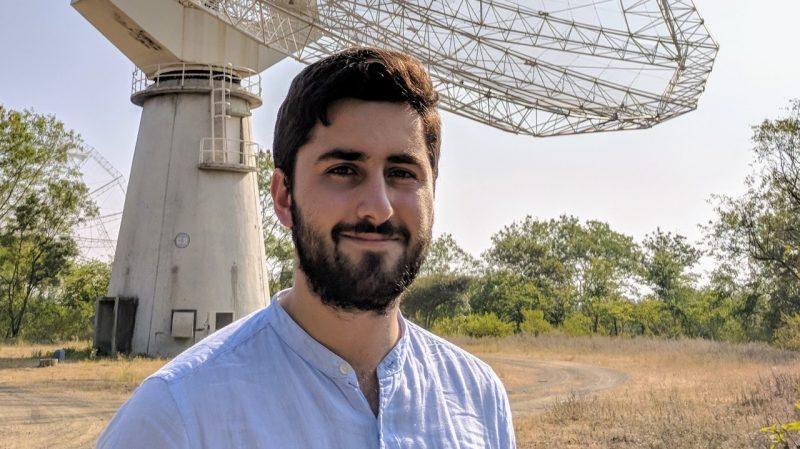

Andrew Zic at The University of Sydney, lead author of the new study. Image via the University of Sydney.

If Proxima Centauri is any indication, then red dwarf stars, by and large, are not the friendliest places for life. Of course, that also depends on other factors for any given planet, such as just how far it is from the star, how strong its magnetic field is if it has one, etc. Some red dwarfs are probably also more active than others, relatively speaking. As Zic commented:

This is probably bad news on the space weather front. It seems likely that the galaxy’s most common stars – red dwarfs – won’t be great places to find life as we know it.

The presence or lack of magnetic fields around the Proxima Centauri planets, or other red dwarf worlds, might be crucial to their habitability. We just don’t know yet how many of them do have such protective barriers against their stars’ radiation. According to Zac:

This remains an open question. How many exoplanets have magnetic fields like ours? But even if there were magnetic fields, given the stellar proximity of habitable zone planets around M-dwarf stars, this might not be enough to protect them.

On a more positive note, however, as Zic noted, red dwarfs are the most common stars, making up about 70% of the stars in our galaxy. That alone might suggest that at least some of their planets could still be habitable.

The Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder (ASKAP) radio telescope, at CSIRO’s Murchison Radio-astronomy Observatory in Western Australia. Image via CSIRO/ Dragonfly Media/ Spatial Source.

These new results can also be applied not only to the study of Earth’s own biosphere as it exists now and has evolved, but in the future as well. Bruce Gendre at the University of Western Australia noted:

Understanding space weather is critical for understanding how our own planet’s biosphere evolved, but also for what the future is.

Bottom line: Astronomers have used radio waves to study space weather around the nearest star to the sun, Proxima Centauri. The results show that the two known planets are probably subjected to intense radiation from their star, casting doubt on their potential habitability.

Source: A Flare-type IV Burst Event from Proxima Centauri and Implications for Space Weather

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/3nOYJLW

Artist’s concept of huge flares on Proxima Centauri, which unleash ionizing radiation. This radiation could be dangerous for any possible life on planets orbiting close to the star. Image via NASA/ ESA/ G. Bacon (STScI)/ Phys.org.

This month, even as some astronomers are talking about a possible mystery radio signal from Proxima Centauri – a signal of interest to astronomers who search for intelligent life beyond Earth – other astronomers are talking about space weather in the vicinity of this star, which is the nearest star to our sun. Space weather in Proxima’s vicinity, they are saying, might make life on its planets difficult or even impossible.

What is space weather?

When we hear about weather, we might think of Earth – sun, clouds, rain, wind and so on – or we might think about conditions on other planets or moons that have atmospheres. Space weather isn’t about that. It’s a sort of “weather” that originates in stars, including our own sun, and that permeates the space near a star. Space weather consists of ionizing radiation released during flares on the sun or other stars. The radiation can be deadly for any life forms that may exist on distant planets. That’s especially true, astronomers say, for red dwarf stars, which have more frequent flares than our sun. Red dwarf stars can be very volatile. Proxima Centauri is a red dwarf star.

EarthSky lunar calendars are back in stock! We’re guaranteed to sell out – get one while you can!

Astronomers at the University of Sydney in Australia announced the new study on December 10, 2020. These researchers used radio waves to detect and probe the space weather in Proxima’s vicinity. Our sun’s nearest neighbor at only 4.2 light-years away, Proxima is known to have at least two planets orbiting it. One, Proxima Centauri b, is almost the same mass as Earth and the other, Proxima Centauri c, is about seven times more massive. Proxima Centauri b also orbits within its star’s habitable zone, where temperatures might allow liquid water to exist on planet’s surface. Sounds promising, right? But the new findings about flares on stars like Proxima suggest a grim prospect for life on the planets in this system.

The researchers published their peer-reviewed findings in The Astronomical Journal on December 9, 2020.

Hubble Space Telescope image of Proxima Centauri, the closest known star to the sun. Read more about this image. Image via ESA/ Hubble/ NASA.

These astronomers worked with CSIRO’s Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder (ASKAP) telescope in Western Australia and the Zadko Telescope at the University of Western Australia, as well as other instruments. Tara Murphy of the University of Sydney helped lead the study.

The new observations corroborate previous studies, showing that the planet known as Proxima Centauri b is subject to intense outbursts of ionizing radiation from its star. Proxima Centauri b is close to the star Proxima Centauri, as Andrew Zic, lead author of the study, explained:

But given Proxima Centauri is a cool, small red-dwarf star, it means this habitable zone is very close to the star; much closer in than Mercury is to our sun. What our research shows is that this makes the planets very vulnerable to dangerous ionizing radiation that could effectively sterilize the planets.

Our sun also emits deadly radiation during its occasional coronal mass ejections. Luckily, Earth is relatively far from our star, in contrast to Proxima’s planets; this radiation doesn’t affect us as powerfully. Plus, Earth has an atmosphere and magnetic field that also help to protect us. Zic commented:

Our own sun regularly emits hot clouds of ionized particles during what we call ‘coronal mass ejections.’ But given the sun is much hotter than Proxima Centauri and other red-dwarf stars, our ‘habitable zone’ is far from the sun’s surface, meaning the Earth is a relatively long way from these events.

Further, the Earth has a very powerful planetary magnetic field that shields us from these intense blasts of solar plasma.

Artist’s concept of Proxima Centauri b, which is about 1.3 times the mass of Earth and orbits within the star’s habitable zone where liquid water could exist. The new data support previous studies, showing that the planet is subjected to intense radiation bursts from its star, putting its potential habitability in doubt. Image via ESO/ M. Kornmesser/ Phys.org.

The new study is the first that definitively links optical flares and radio bursts on a star other than the sun. This means that scientists can now use radio waves to study space weather around distant stars, which will provide important clues as to the potential habitability of any rocky planets orbiting them.

The success of these observations is exciting for astronomers. Tara Murphy at the University of Sydney reflected this in her comments:

This is an exciting result from ASKAP. The incredible data quality allowed us to view the stellar flare from Proxima Centauri over its full evolution in amazing detail.

Most importantly, we can see polarized light, which is a signature of these events. It’s a bit like looking at the star with sunglasses on. Once ASKAP is operating in full survey mode we should be able to observe many more events on nearby stars.

The ASKAP observations were also backed up by NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) and the Zadko Telescope.

Although there could be other explanations, the radio bursts from Proxima Centauri are thought to be connected to coronal mass ejections on the star, just like with our own sun. Zic said:

M-dwarf radio bursts might happen for different reasons than on the sun, where they are usually associated with coronal mass ejections. But it’s highly likely that there are similar events associated with the stellar flares and radio bursts we have seen in this study.

Andrew Zic at The University of Sydney, lead author of the new study. Image via the University of Sydney.

If Proxima Centauri is any indication, then red dwarf stars, by and large, are not the friendliest places for life. Of course, that also depends on other factors for any given planet, such as just how far it is from the star, how strong its magnetic field is if it has one, etc. Some red dwarfs are probably also more active than others, relatively speaking. As Zic commented:

This is probably bad news on the space weather front. It seems likely that the galaxy’s most common stars – red dwarfs – won’t be great places to find life as we know it.

The presence or lack of magnetic fields around the Proxima Centauri planets, or other red dwarf worlds, might be crucial to their habitability. We just don’t know yet how many of them do have such protective barriers against their stars’ radiation. According to Zac:

This remains an open question. How many exoplanets have magnetic fields like ours? But even if there were magnetic fields, given the stellar proximity of habitable zone planets around M-dwarf stars, this might not be enough to protect them.

On a more positive note, however, as Zic noted, red dwarfs are the most common stars, making up about 70% of the stars in our galaxy. That alone might suggest that at least some of their planets could still be habitable.

The Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder (ASKAP) radio telescope, at CSIRO’s Murchison Radio-astronomy Observatory in Western Australia. Image via CSIRO/ Dragonfly Media/ Spatial Source.

These new results can also be applied not only to the study of Earth’s own biosphere as it exists now and has evolved, but in the future as well. Bruce Gendre at the University of Western Australia noted:

Understanding space weather is critical for understanding how our own planet’s biosphere evolved, but also for what the future is.

Bottom line: Astronomers have used radio waves to study space weather around the nearest star to the sun, Proxima Centauri. The results show that the two known planets are probably subjected to intense radiation from their star, casting doubt on their potential habitability.

Source: A Flare-type IV Burst Event from Proxima Centauri and Implications for Space Weather

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/3nOYJLW

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire