Artist’s illustration of the Leonid meteor shower in 1833, one of the most spectacular in history. Image via NJ.com/ Edmund Weiss.

November’s wonderful Leonid meteor shower is active from about November 6 to 30 each year. The peak is expected in 2020 on the morning of November 17. The shower happens as our world crosses the orbital path of Comet 55P/Tempel-Tuttle. Like many comets, Tempel-Tuttle litters its orbit with bits of debris. It’s when this cometary debris enters Earth’s atmosphere and vaporizes that we see the Leonid meteor shower. In 2020, the moon – in a waxing crescent phase – will set in early evening, to provide moon-free skies after midnight when the most meteors typically fall. In a dark sky, with no moon, you can see up to 10 to 15 meteors per hour at the peak.

Although this shower is known for its periodic storms, no Leonid storm is expected this year. Keep reading to learn more.

The lunar calendars are here! Order yours before they’re gone. Makes a great gift.

This isn’t a Leonid meteor. It’s an Orionid. But – as this photo shows – you can sometimes catch a meteor in moonlight, assuming the meteor is bright enough. Photo taken in late October 2016 by Eliot Herman in Tucson, Arizona. Thanks, Eliot!

View larger to see the colors better. | Another photo from Eliot Herman in Tucson, Arizona. This is a double Leonid meteor, captured 2 days before the peak of the shower in 2018. Eliot commented, “The Leonids are the greenest meteors I see.” And he has seen a lot of meteors!

How many Leonid meteors will you see in 2020? The answer always depends on when you watch, where you watch, and on the clarity and darkness of your night sky.

In 2020, we are lucky to have the waxing crescent moon set by early evening, to provide dark skies for this year’s Leonid meteor shower. So you might see as many as 10 to 15 meteors per hour during the dark hours before dawn.

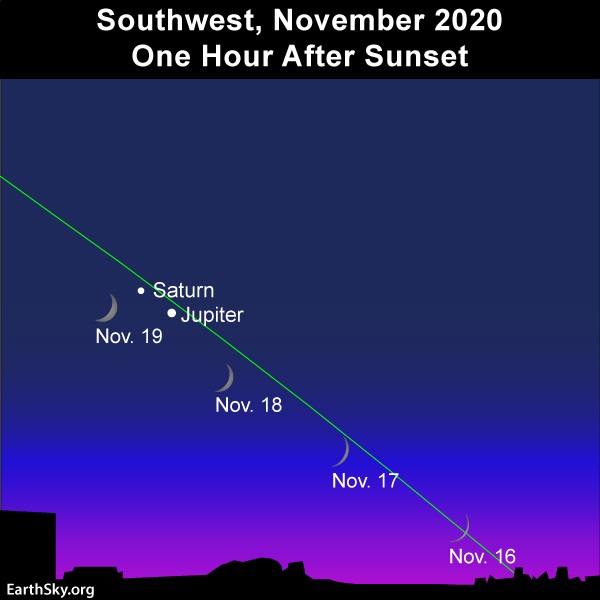

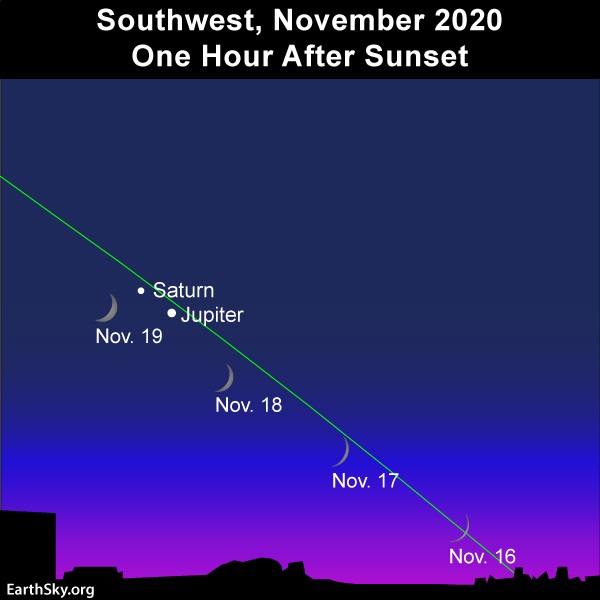

Look for the young moon at nightfall, and for meteors at late night. Read more.

Visit Sunrise Sunset Calendars and check the astronomical twilight and moonrise and moonset boxes to learn these key elements.

Leonid meteors, viewed from space in 1997. Image via NASA.

Where should you watch the meteor shower? We hear lots of reports from people who see meteors from yards, decks, streets and especially highways in and around cities. But the best place to watch a meteor shower is always in the country. Just go far enough from town that glittering stars, the same stars drowned by city lights, begin to pop into view.

Find a place to watch at EarthSky’s Best Places to Stargaze page.

City, state and national parks are often great places to watch meteor showers. Try Googling the name of your state or city with the words city park, state park or national park. Then, be sure to go to the park early in the day and find a wide open area with a good view of the sky in all directions.

When night falls, you’ll probably be impatient to see meteors. But remember that the shower is best after midnight. Catch a nap in early evening if you can. After midnight, lie back comfortably and watch as best you can in all parts of the sky.

Sometimes friends like to watch together, facing different directions. When somebody sees one, they can call out meteor! Then everyone can quickly turn to get a glimpse.

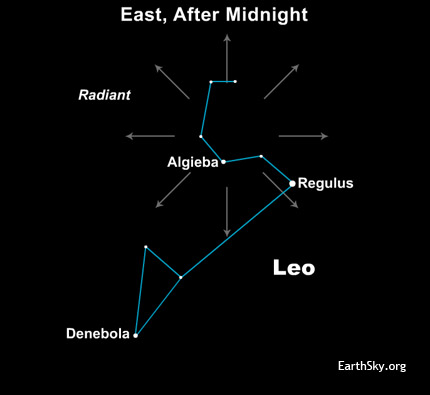

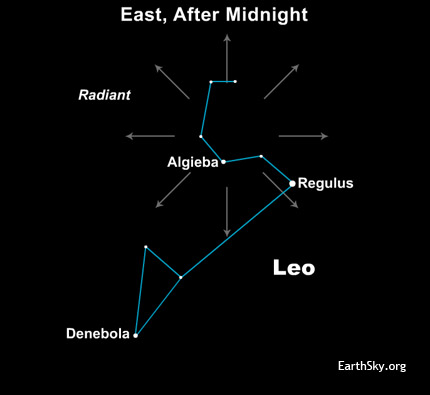

Regulus, the brightest star in the constellation Leo the Lion, dots a backwards question mark of stars known as the Sickle. If you trace all the Leonid meteors backward, they appear to radiate from this area of the sky.

Which direction should I look to see the Leonids? Meteors in annual showers are named for the point in the starry sky from which they appear to radiate. This shower is named for the constellation Leo the Lion, because these meteors radiate outward from the vicinity of stars representing the Lion’s Mane.

If you trace the paths of Leonid meteors backward on the sky’s dome, they do seem to stream from near the star Algieba in the constellation Leo. The point in the sky from which they appear to radiate is called the radiant point. This radiant point is an optical illusion. It’s like standing on railroad tracks and peering off into the distance to see the tracks converge. The illusion of the radiant point is caused by the fact that the meteors – much like the railroad tracks – are moving on parallel paths.

In recent years, people have gotten the mistaken idea that you must know the whereabouts of a meteor shower’s radiant point in order to watch the meteor shower. You don’t need to. The meteors often don’t become visible until they are 30 degrees or so from their radiant point. They are streaking out from the radiant in all directions.

Thus the Leonid meteors – like meteors in all annual showers – will appear in all parts of the sky.

Will the Leonids produce a meteor storm in 2020? No Leonid meteor storm is expected in 2020. Most astronomers say you need more than 1,000 meteors an hour to consider a shower as a storm. That’s a far cry from the 10 to 15 meteors per hour predicted for the Leonids in most years (including this year).

Of course, seeing even one bright meteor can make your night.

The Leonid shower is known for producing meteor storms, though. The parent comet – Tempel-Tuttle – completes a single orbit around the sun about once every 33 years. It releases fresh material every time it enters the inner solar system and approaches the sun. Since the 19th century, skywatchers have watched for Leonid meteor storms about every 33 years, beginning with the meteor storm of 1833, said to produce more than 100,000 meteors an hour.

The next great Leonid storms were seen about 33 years later, in 1866 and 1867.

Then a meteor storm was predicted for 1899, but did not materialize.

It wasn’t until 1966 that the next spectacular Leonid storm was seen, this time over the Americas. In 1966, observers in the southwest United States reported seeing 40 to 50 meteors per second (that’s 2,400 to 3,000 meteors per minute!) during a span of 15 minutes on the morning of November 17, 1966.

In 2001, another great Leonid meteor storm occurred. Spaceweather.com reported:

The display began on Sunday morning, November 18, when Earth glided into a dust cloud shed by Comet Tempel-Tuttle in 1766. Thousands of meteors per hour rained over North America and Hawaii. Then, on Monday morning November 19 (local time in Asia), it happened again: Earth entered a second cometary debris cloud from Tempel-Tuttle. Thousands more Leonids then fell over east Asian countries and Australia.

View SpaceWeather’s 2001 Leonid meteor gallery.

James Younger sent in this photo during the 2015 peak of the Leonid meteor shower. It’s a meteor over the San Juan Islands in the Pacific Northwest, between the U.S. mainland and Vancouver Island, British Columbia.

Bottom line: If you want to watch the 2020 Leonid meteor shower, just know that the hours between midnight and dawn are best for meteor-watching. Fortunately, this year, the waxing crescent moon will set at early evening, providing dark skies for this year’s production!

EarthSky’s meteor shower guide for 2020

Enjoying EarthSky? Sign up for our free daily newsletter today!

Easily locate stars and constellations during any day and time with EarthSky’s Planisphere.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2z7sobX

Artist’s illustration of the Leonid meteor shower in 1833, one of the most spectacular in history. Image via NJ.com/ Edmund Weiss.

November’s wonderful Leonid meteor shower is active from about November 6 to 30 each year. The peak is expected in 2020 on the morning of November 17. The shower happens as our world crosses the orbital path of Comet 55P/Tempel-Tuttle. Like many comets, Tempel-Tuttle litters its orbit with bits of debris. It’s when this cometary debris enters Earth’s atmosphere and vaporizes that we see the Leonid meteor shower. In 2020, the moon – in a waxing crescent phase – will set in early evening, to provide moon-free skies after midnight when the most meteors typically fall. In a dark sky, with no moon, you can see up to 10 to 15 meteors per hour at the peak.

Although this shower is known for its periodic storms, no Leonid storm is expected this year. Keep reading to learn more.

The lunar calendars are here! Order yours before they’re gone. Makes a great gift.

This isn’t a Leonid meteor. It’s an Orionid. But – as this photo shows – you can sometimes catch a meteor in moonlight, assuming the meteor is bright enough. Photo taken in late October 2016 by Eliot Herman in Tucson, Arizona. Thanks, Eliot!

View larger to see the colors better. | Another photo from Eliot Herman in Tucson, Arizona. This is a double Leonid meteor, captured 2 days before the peak of the shower in 2018. Eliot commented, “The Leonids are the greenest meteors I see.” And he has seen a lot of meteors!

How many Leonid meteors will you see in 2020? The answer always depends on when you watch, where you watch, and on the clarity and darkness of your night sky.

In 2020, we are lucky to have the waxing crescent moon set by early evening, to provide dark skies for this year’s Leonid meteor shower. So you might see as many as 10 to 15 meteors per hour during the dark hours before dawn.

Look for the young moon at nightfall, and for meteors at late night. Read more.

Visit Sunrise Sunset Calendars and check the astronomical twilight and moonrise and moonset boxes to learn these key elements.

Leonid meteors, viewed from space in 1997. Image via NASA.

Where should you watch the meteor shower? We hear lots of reports from people who see meteors from yards, decks, streets and especially highways in and around cities. But the best place to watch a meteor shower is always in the country. Just go far enough from town that glittering stars, the same stars drowned by city lights, begin to pop into view.

Find a place to watch at EarthSky’s Best Places to Stargaze page.

City, state and national parks are often great places to watch meteor showers. Try Googling the name of your state or city with the words city park, state park or national park. Then, be sure to go to the park early in the day and find a wide open area with a good view of the sky in all directions.

When night falls, you’ll probably be impatient to see meteors. But remember that the shower is best after midnight. Catch a nap in early evening if you can. After midnight, lie back comfortably and watch as best you can in all parts of the sky.

Sometimes friends like to watch together, facing different directions. When somebody sees one, they can call out meteor! Then everyone can quickly turn to get a glimpse.

Regulus, the brightest star in the constellation Leo the Lion, dots a backwards question mark of stars known as the Sickle. If you trace all the Leonid meteors backward, they appear to radiate from this area of the sky.

Which direction should I look to see the Leonids? Meteors in annual showers are named for the point in the starry sky from which they appear to radiate. This shower is named for the constellation Leo the Lion, because these meteors radiate outward from the vicinity of stars representing the Lion’s Mane.

If you trace the paths of Leonid meteors backward on the sky’s dome, they do seem to stream from near the star Algieba in the constellation Leo. The point in the sky from which they appear to radiate is called the radiant point. This radiant point is an optical illusion. It’s like standing on railroad tracks and peering off into the distance to see the tracks converge. The illusion of the radiant point is caused by the fact that the meteors – much like the railroad tracks – are moving on parallel paths.

In recent years, people have gotten the mistaken idea that you must know the whereabouts of a meteor shower’s radiant point in order to watch the meteor shower. You don’t need to. The meteors often don’t become visible until they are 30 degrees or so from their radiant point. They are streaking out from the radiant in all directions.

Thus the Leonid meteors – like meteors in all annual showers – will appear in all parts of the sky.

Will the Leonids produce a meteor storm in 2020? No Leonid meteor storm is expected in 2020. Most astronomers say you need more than 1,000 meteors an hour to consider a shower as a storm. That’s a far cry from the 10 to 15 meteors per hour predicted for the Leonids in most years (including this year).

Of course, seeing even one bright meteor can make your night.

The Leonid shower is known for producing meteor storms, though. The parent comet – Tempel-Tuttle – completes a single orbit around the sun about once every 33 years. It releases fresh material every time it enters the inner solar system and approaches the sun. Since the 19th century, skywatchers have watched for Leonid meteor storms about every 33 years, beginning with the meteor storm of 1833, said to produce more than 100,000 meteors an hour.

The next great Leonid storms were seen about 33 years later, in 1866 and 1867.

Then a meteor storm was predicted for 1899, but did not materialize.

It wasn’t until 1966 that the next spectacular Leonid storm was seen, this time over the Americas. In 1966, observers in the southwest United States reported seeing 40 to 50 meteors per second (that’s 2,400 to 3,000 meteors per minute!) during a span of 15 minutes on the morning of November 17, 1966.

In 2001, another great Leonid meteor storm occurred. Spaceweather.com reported:

The display began on Sunday morning, November 18, when Earth glided into a dust cloud shed by Comet Tempel-Tuttle in 1766. Thousands of meteors per hour rained over North America and Hawaii. Then, on Monday morning November 19 (local time in Asia), it happened again: Earth entered a second cometary debris cloud from Tempel-Tuttle. Thousands more Leonids then fell over east Asian countries and Australia.

View SpaceWeather’s 2001 Leonid meteor gallery.

James Younger sent in this photo during the 2015 peak of the Leonid meteor shower. It’s a meteor over the San Juan Islands in the Pacific Northwest, between the U.S. mainland and Vancouver Island, British Columbia.

Bottom line: If you want to watch the 2020 Leonid meteor shower, just know that the hours between midnight and dawn are best for meteor-watching. Fortunately, this year, the waxing crescent moon will set at early evening, providing dark skies for this year’s production!

EarthSky’s meteor shower guide for 2020

Enjoying EarthSky? Sign up for our free daily newsletter today!

Easily locate stars and constellations during any day and time with EarthSky’s Planisphere.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2z7sobX

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire