This year, persistent cold temperatures and strong circumpolar winds (also known as the polar vortex) helped contribute to the formation of a large and deep Antarctic ozone hole, just a year after scientists recorded that 2019’s was the smallest since the ozone hole was discovered in 1982, according to a report by NOAA and NASA scientists on October 30, 2020.

The annual Antarctic ozone hole – the 12th-largest on record – reached its peak size for 2020 on September 20, at about 9.6 million square miles (24.8 million square km), roughly three times the area of the continental United States, Observations revealed the nearly complete elimination of ozone in a 4-mile-high (6-km-hight) column of the stratosphere over the South Pole, the scientists report. Diego Loyola, from the German Aerospace Center, said in a statement:

Our observations show that the 2020 ozone hole has grown rapidly since mid-August, and covers most of the Antarctic continent – with its size well above average. What is also interesting to see is that the 2020 ozone hole is also one of the deepest and shows record-low ozone values.

Ozone is a molecule composed of three oxygen atoms. A layer of ozone high in the atmosphere – about 9 to 18 miles (15 to 30 km) up – surrounds the entire Earth. It protects life on our planet from the harmful effects of the sun’s ultraviolet rays. In the 1980s, scientists began to realize that ozone-depleting chemicals, such as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), were creating a thin spot – a hole – in the ozone layer over Antarctica.

The size of the ozone hole over Antarctica fluctuates on a regular basis. From August to October, during the Southern Hemisphere’s late winter as the returning sun’s rays start ozone-depleting reactions, the ozone hole increases in size – reaching a maximum between mid-September and mid-October. When temperatures high up in the stratosphere start to rise in the southern hemisphere, the ozone depletion slows, the polar vortex weakens and finally breaks down, and by the end of December ozone levels return to normal.

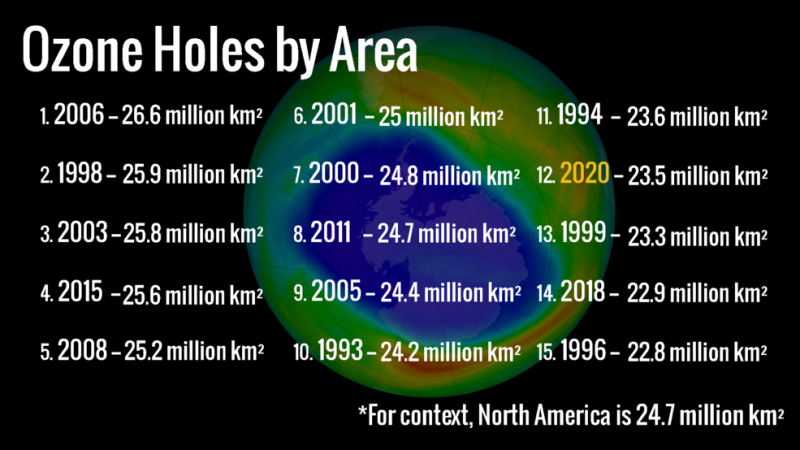

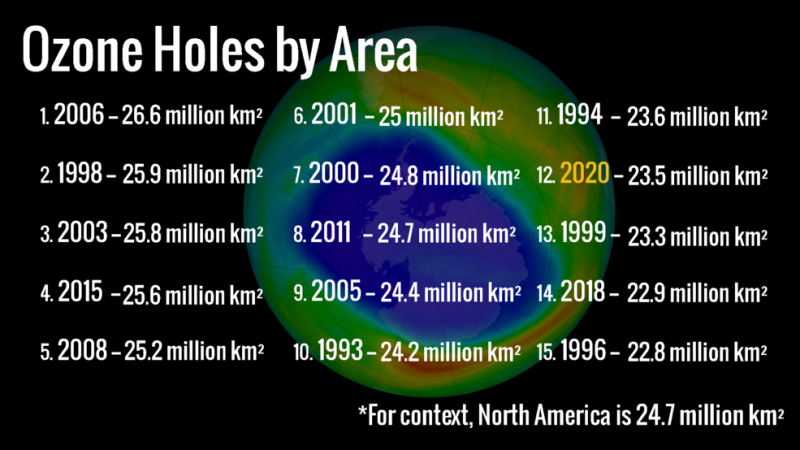

At 23.3 million square km, the average size of the ozone hole between September 7-October 13 used to compare to other years, 2020’s ozone hole is the 12th largest by area. Image via NASA/ NASA Ozone Watch/ Katy Mersmann

Ongoing declines in levels of ozone-depleting chemicals controlled by the Montreal Protocol – the 1987 treaty designed to phase out substances responsible for ozone depletion – prevented the hole from being as large as it would have been under the same weather conditions decades ago, say the scientists. Paul A. Newman is chief scientist for Earth Sciences at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. He said in a statement:

From the year 2000 peak, Antarctic stratosphere chlorine and bromine levels have fallen about 16% towards the natural level. We have a long way to go, but that improvement made a big difference this year. The hole would have been about a million square miles larger if there was still as much chlorine in the stratosphere as there was in 2000.

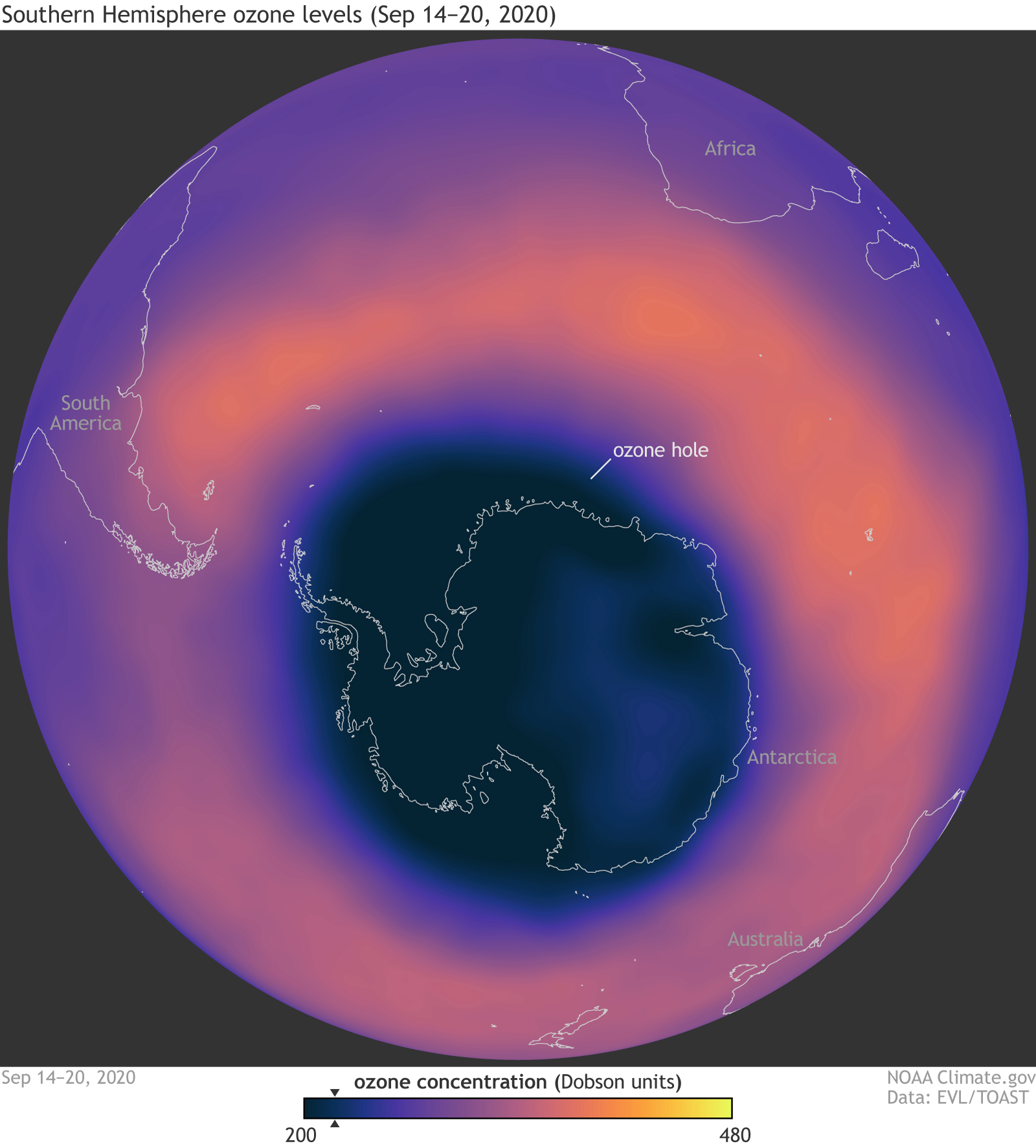

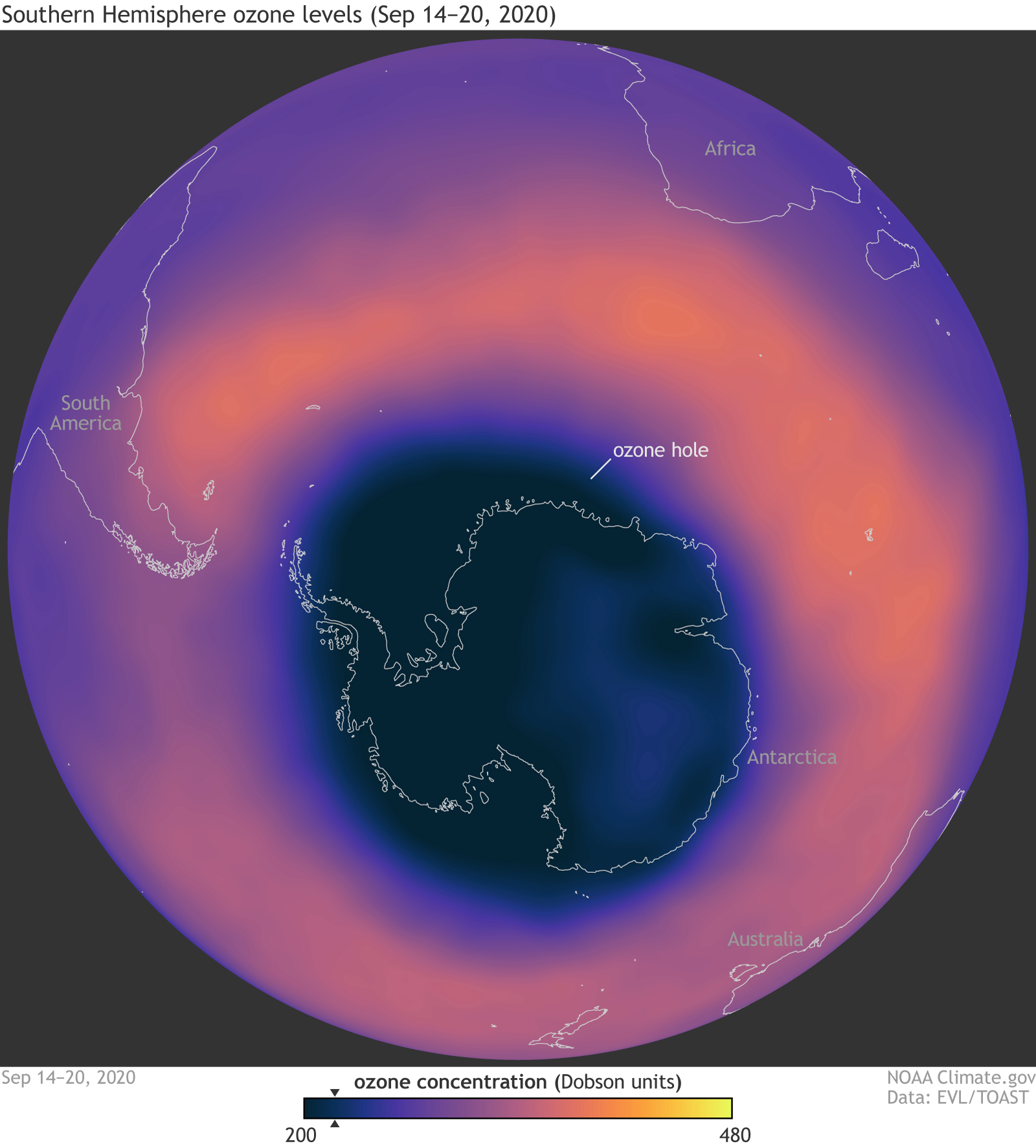

View larger. | Ozone concentration over Antarctica the week of September 14–20, 2020. To allow comparisons from year to year, experts define the “ozone hole” as the area in which ozone levels are below 220 Dobson Units (dark blue, marked with black triangle on color bar). Image via NOAA Climate.gov.

Here’s more from NASA, on what the ozone hole is and why it matters:

Ozone is composed of three oxygen atoms and is highly reactive with other chemicals. In the stratosphere, roughly 7 to 25 miles above Earth’s surface, the ozone layer acts like sunscreen, shielding the planet from ultraviolet radiation that can cause skin cancer and cataracts, suppress immune systems and damage plants and sensitive plankton at the base of the global food chain. By contrast, ozone that forms closer to Earth’s surface through photochemical reactions between the sun and pollution from vehicle emissions and other sources, forms harmful smog in the lower atmosphere.

The Antarctic ozone hole forms during the Southern Hemisphere’s late winter as the returning sun’s rays start ozone-depleting reactions. Cold winter temperatures persisting into the spring enable the ozone depletion process, which is why the “hole” forms over Antarctica. These reactions involve chemically active forms of chlorine and bromine derived from man-made compounds. The chemistry that leads to their formation involves chemical reactions that occur on the surfaces of cloud particles that form in cold stratospheric layers, leading ultimately to runaway reactions that destroy ozone molecules. In warmer temperatures fewer polar stratospheric clouds form and they don’t persist as long, limiting the ozone-depletion process.

This animation shows the size of the ozone hole from September 25 – October 18, 2020.

Learn more about NOAA and NASA efforts to monitor ozone and ozone-depleting gases

Bottom line: 2020’s Antarctic ozone hole is among the largest and deepest in recent years

Via World Meteorological Organization

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/3mPatgy

This year, persistent cold temperatures and strong circumpolar winds (also known as the polar vortex) helped contribute to the formation of a large and deep Antarctic ozone hole, just a year after scientists recorded that 2019’s was the smallest since the ozone hole was discovered in 1982, according to a report by NOAA and NASA scientists on October 30, 2020.

The annual Antarctic ozone hole – the 12th-largest on record – reached its peak size for 2020 on September 20, at about 9.6 million square miles (24.8 million square km), roughly three times the area of the continental United States, Observations revealed the nearly complete elimination of ozone in a 4-mile-high (6-km-hight) column of the stratosphere over the South Pole, the scientists report. Diego Loyola, from the German Aerospace Center, said in a statement:

Our observations show that the 2020 ozone hole has grown rapidly since mid-August, and covers most of the Antarctic continent – with its size well above average. What is also interesting to see is that the 2020 ozone hole is also one of the deepest and shows record-low ozone values.

Ozone is a molecule composed of three oxygen atoms. A layer of ozone high in the atmosphere – about 9 to 18 miles (15 to 30 km) up – surrounds the entire Earth. It protects life on our planet from the harmful effects of the sun’s ultraviolet rays. In the 1980s, scientists began to realize that ozone-depleting chemicals, such as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), were creating a thin spot – a hole – in the ozone layer over Antarctica.

The size of the ozone hole over Antarctica fluctuates on a regular basis. From August to October, during the Southern Hemisphere’s late winter as the returning sun’s rays start ozone-depleting reactions, the ozone hole increases in size – reaching a maximum between mid-September and mid-October. When temperatures high up in the stratosphere start to rise in the southern hemisphere, the ozone depletion slows, the polar vortex weakens and finally breaks down, and by the end of December ozone levels return to normal.

At 23.3 million square km, the average size of the ozone hole between September 7-October 13 used to compare to other years, 2020’s ozone hole is the 12th largest by area. Image via NASA/ NASA Ozone Watch/ Katy Mersmann

Ongoing declines in levels of ozone-depleting chemicals controlled by the Montreal Protocol – the 1987 treaty designed to phase out substances responsible for ozone depletion – prevented the hole from being as large as it would have been under the same weather conditions decades ago, say the scientists. Paul A. Newman is chief scientist for Earth Sciences at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. He said in a statement:

From the year 2000 peak, Antarctic stratosphere chlorine and bromine levels have fallen about 16% towards the natural level. We have a long way to go, but that improvement made a big difference this year. The hole would have been about a million square miles larger if there was still as much chlorine in the stratosphere as there was in 2000.

View larger. | Ozone concentration over Antarctica the week of September 14–20, 2020. To allow comparisons from year to year, experts define the “ozone hole” as the area in which ozone levels are below 220 Dobson Units (dark blue, marked with black triangle on color bar). Image via NOAA Climate.gov.

Here’s more from NASA, on what the ozone hole is and why it matters:

Ozone is composed of three oxygen atoms and is highly reactive with other chemicals. In the stratosphere, roughly 7 to 25 miles above Earth’s surface, the ozone layer acts like sunscreen, shielding the planet from ultraviolet radiation that can cause skin cancer and cataracts, suppress immune systems and damage plants and sensitive plankton at the base of the global food chain. By contrast, ozone that forms closer to Earth’s surface through photochemical reactions between the sun and pollution from vehicle emissions and other sources, forms harmful smog in the lower atmosphere.

The Antarctic ozone hole forms during the Southern Hemisphere’s late winter as the returning sun’s rays start ozone-depleting reactions. Cold winter temperatures persisting into the spring enable the ozone depletion process, which is why the “hole” forms over Antarctica. These reactions involve chemically active forms of chlorine and bromine derived from man-made compounds. The chemistry that leads to their formation involves chemical reactions that occur on the surfaces of cloud particles that form in cold stratospheric layers, leading ultimately to runaway reactions that destroy ozone molecules. In warmer temperatures fewer polar stratospheric clouds form and they don’t persist as long, limiting the ozone-depletion process.

This animation shows the size of the ozone hole from September 25 – October 18, 2020.

Learn more about NOAA and NASA efforts to monitor ozone and ozone-depleting gases

Bottom line: 2020’s Antarctic ozone hole is among the largest and deepest in recent years

Via World Meteorological Organization

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/3mPatgy

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire