NASA’s newest planet-hunting space telescope – the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, aka TESS – has just completed its primary mission, the space agency announced on August 11, 2020. Its initial survey of the sky took two years. In this time, TESS helped revolutionize our knowledge about exoplanets, worlds orbiting distant stars, continuing on from where the Kepler space telescope, NASA’s first planet-hunter, left off.

TESS’ primary mission officially finished on July 4, 2020. After this, TESS will continue with its extended mission phase.

During the two-year survey, TESS images about 75 percent of the sky, and so far has found 66 new confirmed exoplanets and nearly 2,100 additional candidates that are awaiting confirmation. Patricia Boyd, project scientist for TESS at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, said in a statement:

TESS is producing a torrent of high-quality observations providing valuable data across a wide range of science topics.

During the first year, TESS observed 13 different sectors of the sky seen from the southern hemisphere, and then turned its attention to the northern sky in the second year. Each sector is a 24-by-96-degree strip of the sky, and TESS spends about a month surveying each sector.

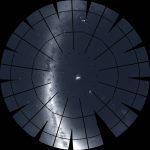

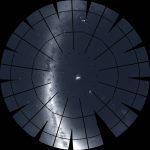

View of the Southern Hemisphere sky from TESS. You can see the glowing band of our Milky Way galaxy (left), the Orion Nebula (top), and the Large Magellanic Cloud (center). The dark lines are gaps between the detectors in TESS’s camera system. Image via NASA/ MIT/ TESS/ Ethan Kruse (USRA).

Patricia Boyd, project scientist for TESS at Goddard Space Flight Center. Image via NASA/ Goddard Space Flight Center.

Now, TESS has returned to watching the northern sky again as it enters its extended mission. With that shift comes some other changes and improvements as well, according to NASA.

TESS is now collecting data faster and more efficiently than it did during the primary mission, NASA said. The telescope’s cameras can now capture a full image every 10 minutes, three times faster than they did in the primary mission. Also, by using a new fast mode, TESS can measure the brightness of thousands of stars every 20 seconds. Previously, the telescope would make similar measurements every two minutes. These improvements are not just good for planet-hunting, they also help TESS better resolve brightness changes caused by stellar oscillations and observe explosive flares from active stars in greater detail.

This extended mission phase will continue until September 2022. TESS will spend the next year observing the southern sky, then will once again go back to surveying the northern sky for a period of 15 months. Those surveys will include observations along the ecliptic – the plane of Earth’s orbit around the sun – that TESS has not yet imaged.

How does TESS find exoplanets?

Like many other telescopes, TESS uses the transit method of detecting exoplanets. That is, its instruments are geared to detecting slight decreases in the brightnesses of stars as planets pass in front of those stars, as seen from Earth. Those temporary dips in brightness are very tiny, but TESS is able to see them, and determine whether they are caused by a planet (in most cases, NASA said, they are).

Last January, NASA announced that TESS had discovered its first Earth-sized planet in the habitable zone of its red dwarf star, TOI 700 d. The habitable zone is the region around a star where temperatures on a rocky planet could allow liquid water to exist. The planet was later confirmed by NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope. This planetary system is just over 100 light-years away in the constellation Dorado. According to Paul Hertz, astrophysics division director at NASA Headquarters in Washington:

TESS was designed and launched specifically to find Earth-sized planets orbiting nearby stars. Planets around nearby stars are easiest to follow-up with larger telescopes in space and on Earth. Discovering TOI 700 d is a key science finding for TESS. Confirming the planet’s size and habitable zone status with Spitzer is another win for Spitzer as it approaches the end of science operations this January.

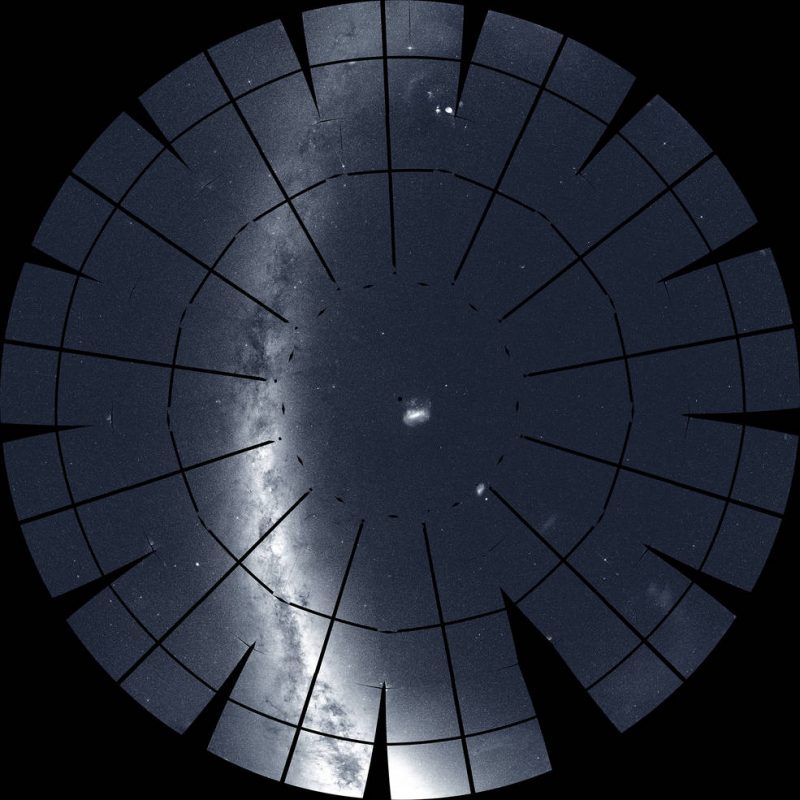

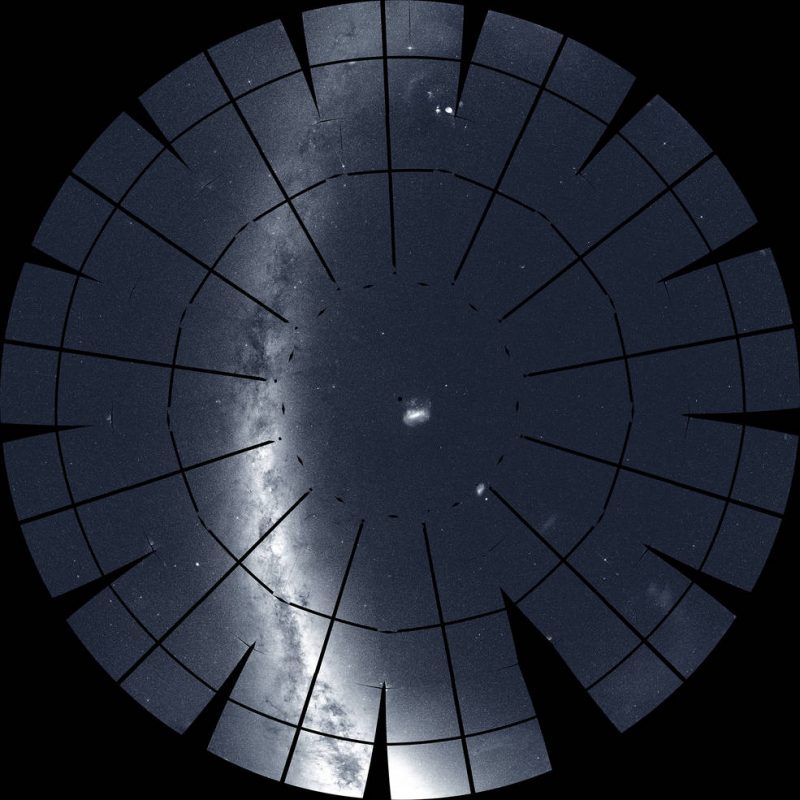

Artist’s concept of TOI 700 d, the first Earth-sized exoplanet that TESS found in the habitable zone of its star. This planetary system is 100 light-years away in the constellation Dorado. Image via Goddard Space Flight Center/ Wikipedia.

TOI 700 d is the outermost of three known planets in the system and the only one in the habitable zone. It measures 20% larger than Earth, orbits its red dwarf star every 37 days and receives from its star 86% of the energy that the sun provides to Earth.

It is expected that TESS will find many more Earth-sized worlds, including ones that are potentially habitable.

In June, scientists reported that TESS found a Neptune-sized planet, AU Mic b, orbiting a very young red dwarf star. Bryson Cale, a doctoral student at George Mason University, said:

AU Mic is a young, nearby M dwarf star. It’s surrounded by a vast debris disk in which moving clumps of dust have been tracked, and now, thanks to TESS and Spitzer, it has a planet with a direct size measurement. There is no other known system that checks all of these important boxes.

The star is only 10 – 20 million years old, and the planet completes an orbit in only 8.5 days.

TESS also recently found its first circumbinary planet – one that orbits two stars – called TOI 1338 b. The two stars orbit each other every 15 days. One is about 10% more massive than our sun, while the other is cooler, dimmer and only one-third the sun’s mass. The planet is about 6.9 times the size of Earth, between the size of Neptune and Saturn.

TESS is good at multi-tasking too, NASA said, and has been studying more than just exoplanets. It has observed the outburst of a comet in our own solar system, as well as numerous exploding stars. It also found surprise eclipses in a well-known binary star system, solved a mystery about a class of pulsating stars, and explored a world experiencing star-modulated seasons.

TESS even caught a black hole in a distant galaxy in the act of tearing apart a sun-like star with its enormous gravity! Thomas Holoien, of the Carnegie Observatories is lead author of a paper that described the findings on September 27, 2019 in The Astrophysical Journal. Holoien said:

TESS data let us see exactly when this destructive event, named ASASSN-19bt, started to get brighter, which we’ve never been able to do before. Because we identified the tidal disruption quickly with the ground-based All-Sky Automated Survey for Supernovae (ASAS-SN), we were able to trigger multiwavelength follow-up observations in the first few days. The early data will be incredibly helpful for modeling the physics of these outbursts.

Last November, it was also announced that TESS would be teaming up with Breakthrough Listen (part of Breakthrough Initiatives) in the search for extraterrestrial intelligence, aka SETI. Basically, TESS will identify objects of interest, such as potentially habitable exoplanets, for other telescopes to point at and search for radio signals or other signs of advanced technologies, called technosignatures.

In only the first couple years of its mission, TESS has not only found thousands of new exoplanets, but has observed and witnessed a wide variety of incredible cosmic objects and phenomena. What else will it find in the years ahead?

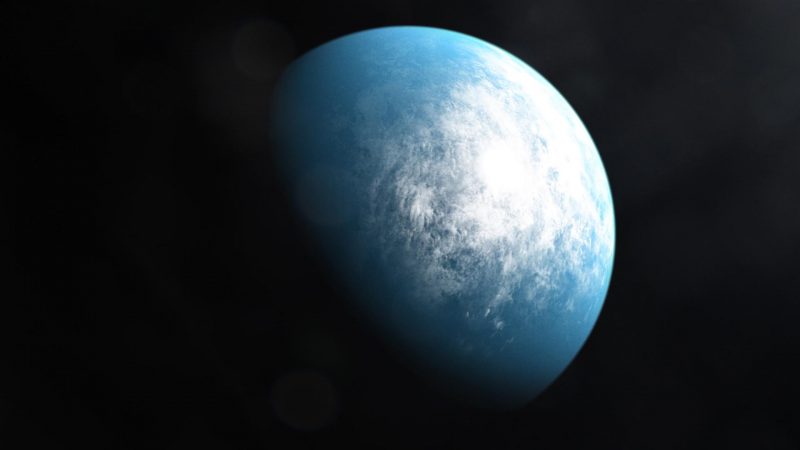

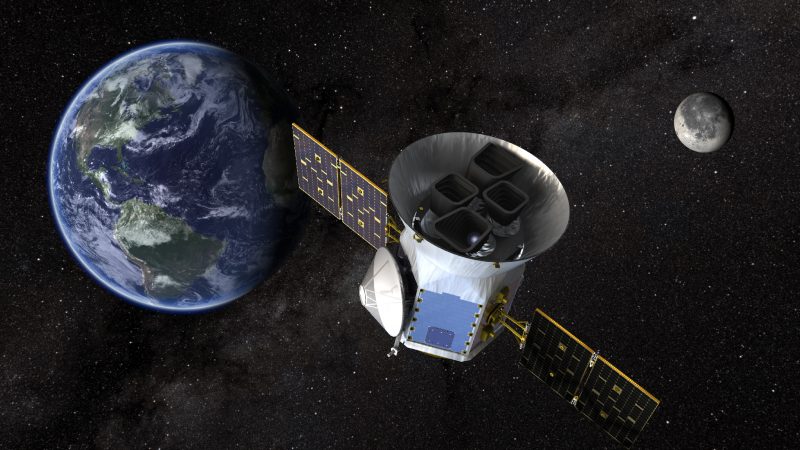

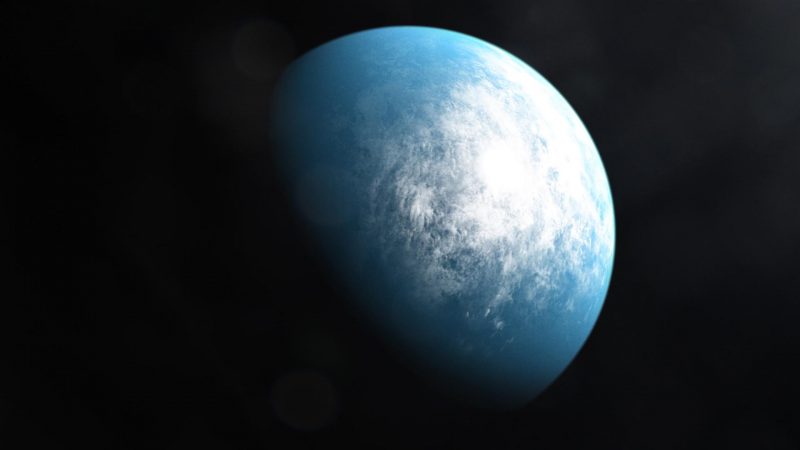

Artist’s illustration of TESS. The planet-hunting space telescope has now completed its primary mission and is now moving into its extended mission. It has already found nearly 2,100 exoplanet candidates and 66 confirmed new worlds. Image via NASA/ Goddard Space Flight Center.

Bottom line: NASA’s planet-hunting space telescope TESS has completed its primary mission.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/320NKWd

NASA’s newest planet-hunting space telescope – the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, aka TESS – has just completed its primary mission, the space agency announced on August 11, 2020. Its initial survey of the sky took two years. In this time, TESS helped revolutionize our knowledge about exoplanets, worlds orbiting distant stars, continuing on from where the Kepler space telescope, NASA’s first planet-hunter, left off.

TESS’ primary mission officially finished on July 4, 2020. After this, TESS will continue with its extended mission phase.

During the two-year survey, TESS images about 75 percent of the sky, and so far has found 66 new confirmed exoplanets and nearly 2,100 additional candidates that are awaiting confirmation. Patricia Boyd, project scientist for TESS at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, said in a statement:

TESS is producing a torrent of high-quality observations providing valuable data across a wide range of science topics.

During the first year, TESS observed 13 different sectors of the sky seen from the southern hemisphere, and then turned its attention to the northern sky in the second year. Each sector is a 24-by-96-degree strip of the sky, and TESS spends about a month surveying each sector.

View of the Southern Hemisphere sky from TESS. You can see the glowing band of our Milky Way galaxy (left), the Orion Nebula (top), and the Large Magellanic Cloud (center). The dark lines are gaps between the detectors in TESS’s camera system. Image via NASA/ MIT/ TESS/ Ethan Kruse (USRA).

Patricia Boyd, project scientist for TESS at Goddard Space Flight Center. Image via NASA/ Goddard Space Flight Center.

Now, TESS has returned to watching the northern sky again as it enters its extended mission. With that shift comes some other changes and improvements as well, according to NASA.

TESS is now collecting data faster and more efficiently than it did during the primary mission, NASA said. The telescope’s cameras can now capture a full image every 10 minutes, three times faster than they did in the primary mission. Also, by using a new fast mode, TESS can measure the brightness of thousands of stars every 20 seconds. Previously, the telescope would make similar measurements every two minutes. These improvements are not just good for planet-hunting, they also help TESS better resolve brightness changes caused by stellar oscillations and observe explosive flares from active stars in greater detail.

This extended mission phase will continue until September 2022. TESS will spend the next year observing the southern sky, then will once again go back to surveying the northern sky for a period of 15 months. Those surveys will include observations along the ecliptic – the plane of Earth’s orbit around the sun – that TESS has not yet imaged.

How does TESS find exoplanets?

Like many other telescopes, TESS uses the transit method of detecting exoplanets. That is, its instruments are geared to detecting slight decreases in the brightnesses of stars as planets pass in front of those stars, as seen from Earth. Those temporary dips in brightness are very tiny, but TESS is able to see them, and determine whether they are caused by a planet (in most cases, NASA said, they are).

Last January, NASA announced that TESS had discovered its first Earth-sized planet in the habitable zone of its red dwarf star, TOI 700 d. The habitable zone is the region around a star where temperatures on a rocky planet could allow liquid water to exist. The planet was later confirmed by NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope. This planetary system is just over 100 light-years away in the constellation Dorado. According to Paul Hertz, astrophysics division director at NASA Headquarters in Washington:

TESS was designed and launched specifically to find Earth-sized planets orbiting nearby stars. Planets around nearby stars are easiest to follow-up with larger telescopes in space and on Earth. Discovering TOI 700 d is a key science finding for TESS. Confirming the planet’s size and habitable zone status with Spitzer is another win for Spitzer as it approaches the end of science operations this January.

Artist’s concept of TOI 700 d, the first Earth-sized exoplanet that TESS found in the habitable zone of its star. This planetary system is 100 light-years away in the constellation Dorado. Image via Goddard Space Flight Center/ Wikipedia.

TOI 700 d is the outermost of three known planets in the system and the only one in the habitable zone. It measures 20% larger than Earth, orbits its red dwarf star every 37 days and receives from its star 86% of the energy that the sun provides to Earth.

It is expected that TESS will find many more Earth-sized worlds, including ones that are potentially habitable.

In June, scientists reported that TESS found a Neptune-sized planet, AU Mic b, orbiting a very young red dwarf star. Bryson Cale, a doctoral student at George Mason University, said:

AU Mic is a young, nearby M dwarf star. It’s surrounded by a vast debris disk in which moving clumps of dust have been tracked, and now, thanks to TESS and Spitzer, it has a planet with a direct size measurement. There is no other known system that checks all of these important boxes.

The star is only 10 – 20 million years old, and the planet completes an orbit in only 8.5 days.

TESS also recently found its first circumbinary planet – one that orbits two stars – called TOI 1338 b. The two stars orbit each other every 15 days. One is about 10% more massive than our sun, while the other is cooler, dimmer and only one-third the sun’s mass. The planet is about 6.9 times the size of Earth, between the size of Neptune and Saturn.

TESS is good at multi-tasking too, NASA said, and has been studying more than just exoplanets. It has observed the outburst of a comet in our own solar system, as well as numerous exploding stars. It also found surprise eclipses in a well-known binary star system, solved a mystery about a class of pulsating stars, and explored a world experiencing star-modulated seasons.

TESS even caught a black hole in a distant galaxy in the act of tearing apart a sun-like star with its enormous gravity! Thomas Holoien, of the Carnegie Observatories is lead author of a paper that described the findings on September 27, 2019 in The Astrophysical Journal. Holoien said:

TESS data let us see exactly when this destructive event, named ASASSN-19bt, started to get brighter, which we’ve never been able to do before. Because we identified the tidal disruption quickly with the ground-based All-Sky Automated Survey for Supernovae (ASAS-SN), we were able to trigger multiwavelength follow-up observations in the first few days. The early data will be incredibly helpful for modeling the physics of these outbursts.

Last November, it was also announced that TESS would be teaming up with Breakthrough Listen (part of Breakthrough Initiatives) in the search for extraterrestrial intelligence, aka SETI. Basically, TESS will identify objects of interest, such as potentially habitable exoplanets, for other telescopes to point at and search for radio signals or other signs of advanced technologies, called technosignatures.

In only the first couple years of its mission, TESS has not only found thousands of new exoplanets, but has observed and witnessed a wide variety of incredible cosmic objects and phenomena. What else will it find in the years ahead?

Artist’s illustration of TESS. The planet-hunting space telescope has now completed its primary mission and is now moving into its extended mission. It has already found nearly 2,100 exoplanet candidates and 66 confirmed new worlds. Image via NASA/ Goddard Space Flight Center.

Bottom line: NASA’s planet-hunting space telescope TESS has completed its primary mission.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/320NKWd

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire