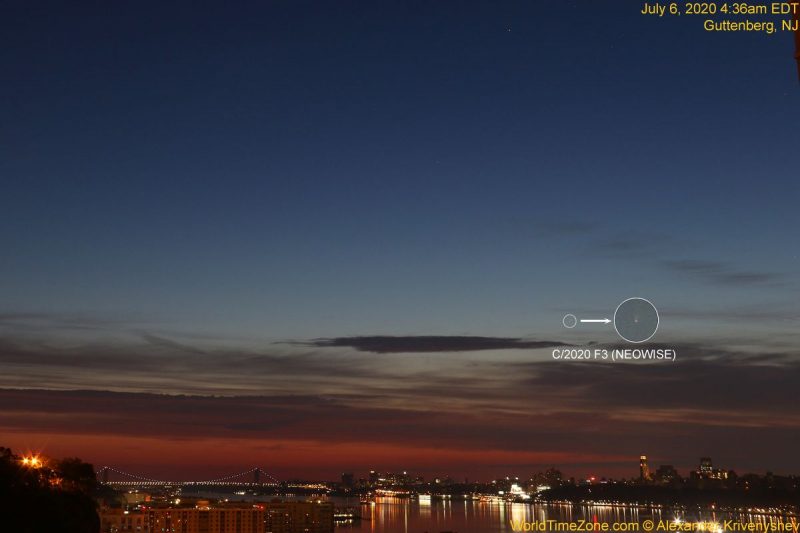

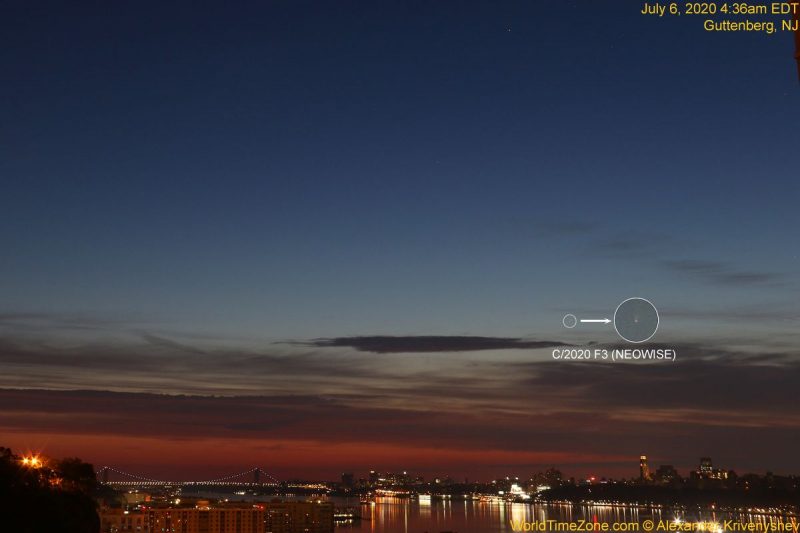

View at EarthSky Community Photos. | In early July 2020, people are getting amazing shots of comet C/2020 F3 (NEOWISE). It’s not a great comet, but it’s a pretty good one! Alexander Krivenyshev in Guttenberg, New Jersey – of the website WorldTimeZone.com – wrote: “Despite a layer of clouds on the horizon, I was able to capture my first comet over New York City on the early morning of July 6, 2020.” Cool shot, Alexander! Thank you. Here’s how to see Comet NEOWISE.

We’re now treated to a near-constant barrage of wonderful comet photos – including those coming in this week of comet C/2020 F3 (NEOWISE). Most are from experienced astrophotographers, most with excellent skies, employing telescopes and modern cameras and sometimes later creating composites of several images. We now sometimes see comet images from the International Space Station, too. Meanwhile, from the ground and with the eye alone? Yes, NEOWISE is a nice comet. But most will need binoculars to see it. The last two Great Comets – McNaught in 2007 and Lovejoy in 2011 – were mainly seen under Southern Hemisphere skies. Not since Hale-Bopp in 1996-97 has the Northern Hemisphere seen a magnificent comet.

What’s more, some skygazers wouldn’t even classify Hale-Bopp as a Great Comet. In that case, we in the Northern Hemisphere might have to look all the way back to comet West in 1976 – 44 years ago – to find a truly great Great Comet. When will we see the next one?

Let’s consider some of the incredible comets of recent times and historic records, to find out when the Northern and Southern Hemispheres might expect to see the next Great Comet.

A night under the stars and comet Hale-Bopp in 1997. It remained visible to the unaided eye for 18 months, and many in the Northern Hemisphere saw it. Photo via Jerry Lodriguss/ www.astropix.com. Used with permission.

First, how are we defining a Great Comet? There’s no official definition. The label Great Comet stems from some combination of a comet’s brightness, longevity and breadth across the sky.

For purposes of this article, to consider the question of Great Comets of the north and south, and their frequency, we’ll define Great Comets as those that achieve a brightness equal to the brightest planet Venus (magnitude -3 to -4) or brighter with tails that span 30 degrees or more of sky.

We can consider some other major comets, too, those that reached magnitude 1 or brighter – in other words, they became as bright as the brightest stars – with tails spanning 15 degrees or more. These major comets would have been visible long enough for Earth’s citizenry to take notice (some impressive comets have such extreme orbits that they aren’t visible long, and hardly anyone besides astronomers notices them).

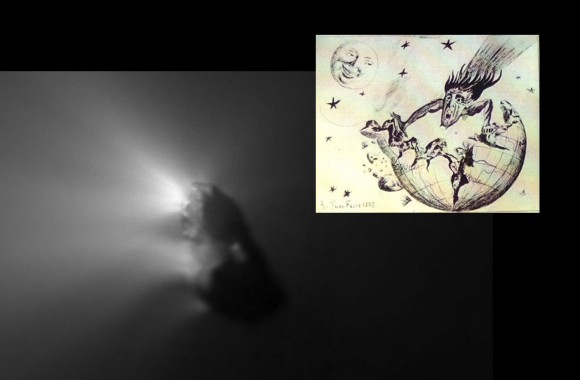

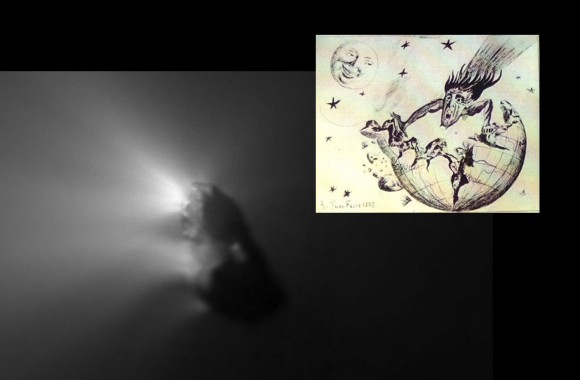

Halley’s comet in 1986 seconds before closest approach by the ESA spacecraft Giotto. The inset shows comets as depicted in popular illustration duration the time of Halley’s 1910 apparition. Big difference! Image via Giotto/ ESA.

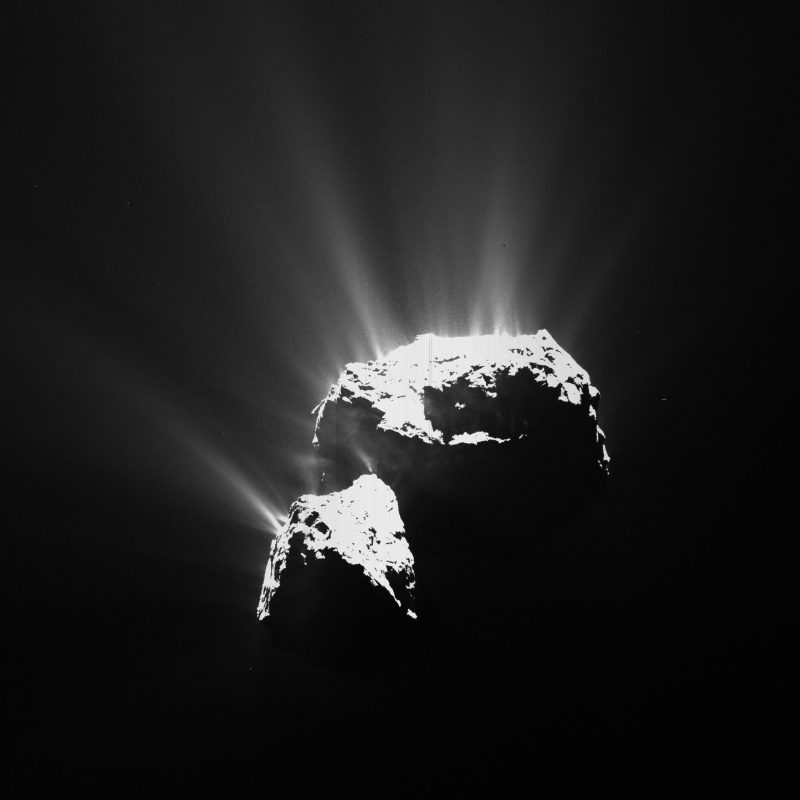

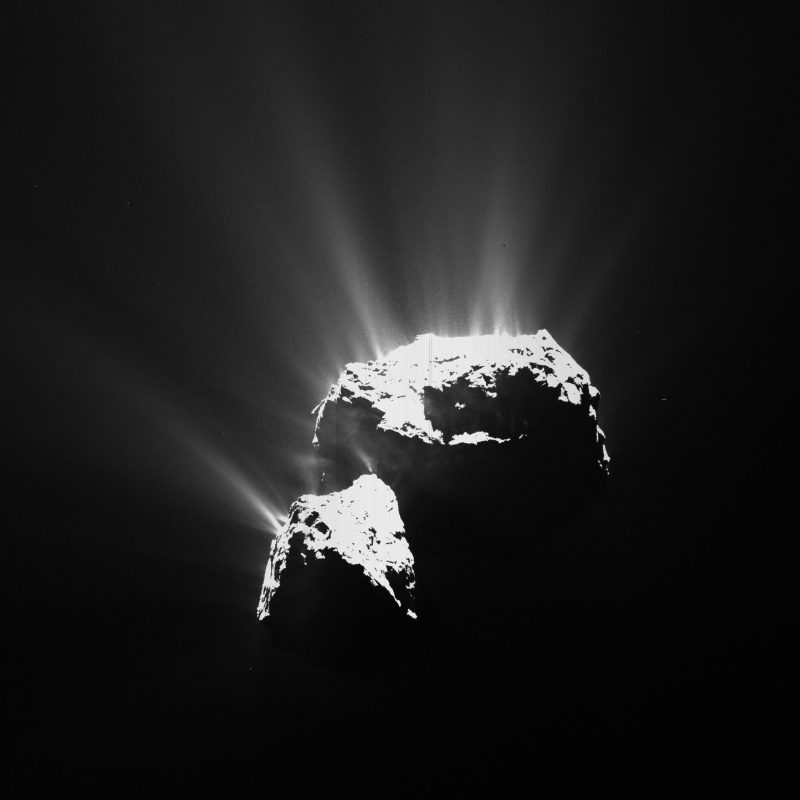

Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko in the days before its perihelion, or closest point to the sun, in August 2015, as seen by ESA’s Rosetta spacecraft. The image is intentionally overexposed to show the dust jets leaving the comet’s surface during its most active phase. Image via Rosetta/ OSIRIS Image Viewer/ Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research.

Consider, also, that humanity’s ability to view the heavens has completely changed in the last 50 years.

In that time, space travel has become a reality and solid-state electronics have revolutionized photography. Space probes have been sent to comets, most recently the European Space Agency’s Rosetta spacecraft, which spent two years (2014 to 2016) becoming intimately acquainted with comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko.

And the transistor and sensitive solid-state detectors revolutionized astrophotography providing amateurs with observing capabilities far exceeding professionals prior to modern electronics.

Everyone agrees that comet Lovejoy of 2011 was a Great Comet. Unfortunately, it was seen mainly from Earth’s Southern Hemisphere. In this image, comet Lovejoy is visible near Earth’s horizon behind airglow. December 22, 2011, image via NASA astronaut Dan Burbank, Expedition 30 commander, aboard the International Space Station/ Wikimedia Commons.

Comet Lovejoy (C/2014 Q2), photographed January 18, 2015, from Austria. This isn’t the comet Lovejoy that the Southern Hemisphere knew and loved as the Great Comet of 2011. Instead, it’s the rather spectacular comet Lovejoy of late 2014 and early 2015, made famous by the steady advances in digital astrophotography. Photo via G. Rhemann.

The years 1996-1997 were all about Hale-Bopp for comet fans. It was primarily a Northern Hemisphere comet. For weeks on end, Hale-Bopp was a fixture in our western sky, and it probably became one of the most-viewed comets in history.

This comet was indeed a major comet, but a Great Comet?

Nearly all comets have short periods of visibility. Hale-Bopp literally smashed the previous record for longevity in our skies, which had been held for nearly two centuries by the Great Comet of 1811. The 1811 comet remained visible to the unaided eye for nine months. Hale-Bopp was visible for a historic 18 months, truly the Cal Ripken Jr. of comets.

Hale-Bopp was bright early on, nearly but not quite as bright as Venus. The size of its nucleus – the icy core of the comet, hurtling through space – was estimated to be 60 kilometers +/- 20 km (37 miles +/- 12). That makes Hale-Bopp’s nucleus some six times larger than the nucleus of Halley’s comet and 20 times that of Rosetta’s comet, 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko.

Hale-Bopp had a long tail, up to 30 degrees long, but what was visible and bright was relatively a short tail, less than 10 degrees long, for nearly its entire period of visibility. Yes, some former Great Comets did not have 30 degree or longer tails, but those comets were, instead, extremely bright.

Bright generally means as bright as Venus or brighter. Hale-Bopp was not quite that bright. Some Great Comets are visible in daylight, but Hale-Bopp was not.

Finally, probably, we have to concede that Hale-Bopp straddles the edge of greatness.

Comet West as seen on January 11, 1974, and comet Kohoutek (inset) in 1973. Photo via University of Arizona/ Catalina Observatory/ NASA.

In 1973, skygazers were alerted to the early discovery of a comet called Kohoutek. At the distance at which it was discovered and its brightness, astronomers projected that this was going to be a Comet of the Century, perhaps a daylight comet, a once-in-a-lifetime event.

But Kohoutek fizzled. It really disappointed skygazers even though, for professional astronomers, the drawn-out observations of Kohoutek were quite valuable.

Astronomers thought they had learned a lesson from Kohoutek. Too many astronomers stood outdoors at public “star parties” that year, trying to show a disappointed public a difficult-to-see comet.

Unfortunately, the lesson learned from this comet led astronomers to downplay the next contender for greatness: comet West in 1976. That was too bad, because comet West did not disappoint. It was a magnificent comet! Still, many average skygazers were left out because astronomers remained quiet and the media did not report on it. Thus comet West was not seen and appreciated as it should have been.

Comet Lovejoy (2011) as seen from Santiago, Chile, December 22, 2011. Photo via Y. Beletsky (LCO)/ ESO.

From comet West, fast forward a full 31 years to 2007 and the next truly Great Comet (sidestepping Hale-Bopp). The comet hunter Robert H. McNaught – who has discovered more than 50 comets – discovered it. This 2007 comet is sometimes called the Great Comet of 2007. You’re in the Northern Hemisphere and don’t remember a Great Comet that year? That’s because, due to the inclination and high eccentricity of comet orbits, many are viewable from only one Earth hemisphere or the other. That was the case for comet McNaught in 2007.

Only Southern Hemisphere skygazers had a chance to become enamored of comet McNaught in 2007. Then, just four years later, another Great Comet appeared in Southern Hemisphere skies, comet Lovejoy of 2011. Northerners could only watch these two comets from a distance, through the wizardry of the digital age.

Or they could hitch a costly ride to place themselves under the southern skies.

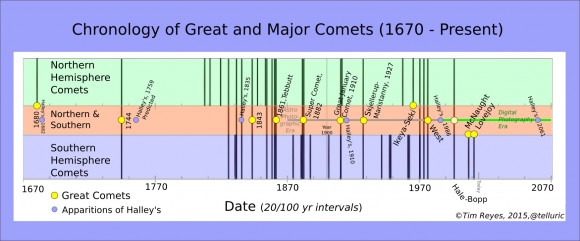

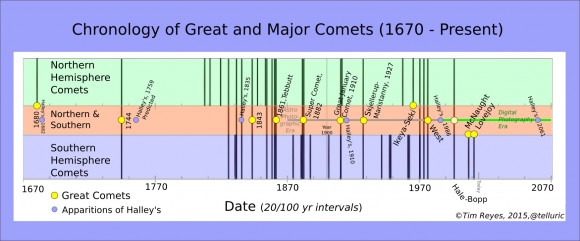

So now consider the following chart which plots the major and Great Comets going back to 1680. Bear in mind that astronomical records appear to have reached a high level of fidelity about 200 years ago. Looking at this data statistically, what does it reveal?

Chronological chart of Great Comets and major comets, 1670 to present. Great Comets are marked with a yellow dot and all comets are displayed relative to their spheres of visibility – north, south or both. Image via T. Reyes/ Harvard University/ Space.com.

On average, every five years, one can expect to see a major comet visible from the Earth. However, the variability around that average is also about five years (one standard deviation).

This means that, on average, a major comet arrives every five to 10 years.

Sometimes the visitations are clustered. A prime example is the years 1910 and 1911, when four major comets crossed the sky.

The data also reveal that Great Comets arrive on average every 20 years. The variability is 10 years, as represented by a standard deviation around the average. So truly Great Comets may be visible from Earth every 20 to 30 years. Some centuries might have two or three (1800s) while others, four or more (1900s).

Great Comet of 1861, also known as C/1861 J1 or comet Tebbutt. Beyond this date, astrophotography began to capture Great Comets and major comets. Illustration via E. Weiß/ Bilderatlas der Sternenwelt.

Statistically, accounting for comet activity over 250 years – 38 major comets – is pretty sparse data, but one can see in the plot a historic trend. It is possible that if data could reveal a leaning towards one hemisphere, it could be an indicator that the Oort Cloud north or south of the ecliptic plane was affected by some object, e.g. a passing star. There is no indication of this in the records.

Does it answer the question? Has the Northern Hemisphere missed out on Great Comets?

There is certainly a recent trend towards the Southern Hemisphere for Great Comets. The data reveal that the long-term trend for both the Southern and Northern Hemispheres is a Great Comet every 25 to 40 years.

But, if you discount Hale-Bopp, then the last Great Comet for the Northern Hemisphere was Comet West, 44 years ago. Even if you consider Hale-Bopp as great, 23 years have passed.

It would seem that the north is statistically ready to receive its next Great Comet. Bring it on!

Comet Hale-Bopp with its prominent dust (white) and plasma (blue) tails. Photo taken from Linz, Austria. Image via E. Kolmhofer, H. Raab/ Johannes-Kepler-Observatory.

Bottom line: The Southern Hemisphere has had two Great Comets in this century: McNaught in 2007 and Lovejoy in 2011. But what about the Northern Hemisphere? Our last widely seen comet was Hale-Bopp in 1996-97. Comet West in 1976 was probably our last Great Comet. We’re due for one!

Read more and see charts: How to see Comet NEOWISE

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2PJeNPz

View at EarthSky Community Photos. | In early July 2020, people are getting amazing shots of comet C/2020 F3 (NEOWISE). It’s not a great comet, but it’s a pretty good one! Alexander Krivenyshev in Guttenberg, New Jersey – of the website WorldTimeZone.com – wrote: “Despite a layer of clouds on the horizon, I was able to capture my first comet over New York City on the early morning of July 6, 2020.” Cool shot, Alexander! Thank you. Here’s how to see Comet NEOWISE.

We’re now treated to a near-constant barrage of wonderful comet photos – including those coming in this week of comet C/2020 F3 (NEOWISE). Most are from experienced astrophotographers, most with excellent skies, employing telescopes and modern cameras and sometimes later creating composites of several images. We now sometimes see comet images from the International Space Station, too. Meanwhile, from the ground and with the eye alone? Yes, NEOWISE is a nice comet. But most will need binoculars to see it. The last two Great Comets – McNaught in 2007 and Lovejoy in 2011 – were mainly seen under Southern Hemisphere skies. Not since Hale-Bopp in 1996-97 has the Northern Hemisphere seen a magnificent comet.

What’s more, some skygazers wouldn’t even classify Hale-Bopp as a Great Comet. In that case, we in the Northern Hemisphere might have to look all the way back to comet West in 1976 – 44 years ago – to find a truly great Great Comet. When will we see the next one?

Let’s consider some of the incredible comets of recent times and historic records, to find out when the Northern and Southern Hemispheres might expect to see the next Great Comet.

A night under the stars and comet Hale-Bopp in 1997. It remained visible to the unaided eye for 18 months, and many in the Northern Hemisphere saw it. Photo via Jerry Lodriguss/ www.astropix.com. Used with permission.

First, how are we defining a Great Comet? There’s no official definition. The label Great Comet stems from some combination of a comet’s brightness, longevity and breadth across the sky.

For purposes of this article, to consider the question of Great Comets of the north and south, and their frequency, we’ll define Great Comets as those that achieve a brightness equal to the brightest planet Venus (magnitude -3 to -4) or brighter with tails that span 30 degrees or more of sky.

We can consider some other major comets, too, those that reached magnitude 1 or brighter – in other words, they became as bright as the brightest stars – with tails spanning 15 degrees or more. These major comets would have been visible long enough for Earth’s citizenry to take notice (some impressive comets have such extreme orbits that they aren’t visible long, and hardly anyone besides astronomers notices them).

Halley’s comet in 1986 seconds before closest approach by the ESA spacecraft Giotto. The inset shows comets as depicted in popular illustration duration the time of Halley’s 1910 apparition. Big difference! Image via Giotto/ ESA.

Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko in the days before its perihelion, or closest point to the sun, in August 2015, as seen by ESA’s Rosetta spacecraft. The image is intentionally overexposed to show the dust jets leaving the comet’s surface during its most active phase. Image via Rosetta/ OSIRIS Image Viewer/ Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research.

Consider, also, that humanity’s ability to view the heavens has completely changed in the last 50 years.

In that time, space travel has become a reality and solid-state electronics have revolutionized photography. Space probes have been sent to comets, most recently the European Space Agency’s Rosetta spacecraft, which spent two years (2014 to 2016) becoming intimately acquainted with comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko.

And the transistor and sensitive solid-state detectors revolutionized astrophotography providing amateurs with observing capabilities far exceeding professionals prior to modern electronics.

Everyone agrees that comet Lovejoy of 2011 was a Great Comet. Unfortunately, it was seen mainly from Earth’s Southern Hemisphere. In this image, comet Lovejoy is visible near Earth’s horizon behind airglow. December 22, 2011, image via NASA astronaut Dan Burbank, Expedition 30 commander, aboard the International Space Station/ Wikimedia Commons.

Comet Lovejoy (C/2014 Q2), photographed January 18, 2015, from Austria. This isn’t the comet Lovejoy that the Southern Hemisphere knew and loved as the Great Comet of 2011. Instead, it’s the rather spectacular comet Lovejoy of late 2014 and early 2015, made famous by the steady advances in digital astrophotography. Photo via G. Rhemann.

The years 1996-1997 were all about Hale-Bopp for comet fans. It was primarily a Northern Hemisphere comet. For weeks on end, Hale-Bopp was a fixture in our western sky, and it probably became one of the most-viewed comets in history.

This comet was indeed a major comet, but a Great Comet?

Nearly all comets have short periods of visibility. Hale-Bopp literally smashed the previous record for longevity in our skies, which had been held for nearly two centuries by the Great Comet of 1811. The 1811 comet remained visible to the unaided eye for nine months. Hale-Bopp was visible for a historic 18 months, truly the Cal Ripken Jr. of comets.

Hale-Bopp was bright early on, nearly but not quite as bright as Venus. The size of its nucleus – the icy core of the comet, hurtling through space – was estimated to be 60 kilometers +/- 20 km (37 miles +/- 12). That makes Hale-Bopp’s nucleus some six times larger than the nucleus of Halley’s comet and 20 times that of Rosetta’s comet, 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko.

Hale-Bopp had a long tail, up to 30 degrees long, but what was visible and bright was relatively a short tail, less than 10 degrees long, for nearly its entire period of visibility. Yes, some former Great Comets did not have 30 degree or longer tails, but those comets were, instead, extremely bright.

Bright generally means as bright as Venus or brighter. Hale-Bopp was not quite that bright. Some Great Comets are visible in daylight, but Hale-Bopp was not.

Finally, probably, we have to concede that Hale-Bopp straddles the edge of greatness.

Comet West as seen on January 11, 1974, and comet Kohoutek (inset) in 1973. Photo via University of Arizona/ Catalina Observatory/ NASA.

In 1973, skygazers were alerted to the early discovery of a comet called Kohoutek. At the distance at which it was discovered and its brightness, astronomers projected that this was going to be a Comet of the Century, perhaps a daylight comet, a once-in-a-lifetime event.

But Kohoutek fizzled. It really disappointed skygazers even though, for professional astronomers, the drawn-out observations of Kohoutek were quite valuable.

Astronomers thought they had learned a lesson from Kohoutek. Too many astronomers stood outdoors at public “star parties” that year, trying to show a disappointed public a difficult-to-see comet.

Unfortunately, the lesson learned from this comet led astronomers to downplay the next contender for greatness: comet West in 1976. That was too bad, because comet West did not disappoint. It was a magnificent comet! Still, many average skygazers were left out because astronomers remained quiet and the media did not report on it. Thus comet West was not seen and appreciated as it should have been.

Comet Lovejoy (2011) as seen from Santiago, Chile, December 22, 2011. Photo via Y. Beletsky (LCO)/ ESO.

From comet West, fast forward a full 31 years to 2007 and the next truly Great Comet (sidestepping Hale-Bopp). The comet hunter Robert H. McNaught – who has discovered more than 50 comets – discovered it. This 2007 comet is sometimes called the Great Comet of 2007. You’re in the Northern Hemisphere and don’t remember a Great Comet that year? That’s because, due to the inclination and high eccentricity of comet orbits, many are viewable from only one Earth hemisphere or the other. That was the case for comet McNaught in 2007.

Only Southern Hemisphere skygazers had a chance to become enamored of comet McNaught in 2007. Then, just four years later, another Great Comet appeared in Southern Hemisphere skies, comet Lovejoy of 2011. Northerners could only watch these two comets from a distance, through the wizardry of the digital age.

Or they could hitch a costly ride to place themselves under the southern skies.

So now consider the following chart which plots the major and Great Comets going back to 1680. Bear in mind that astronomical records appear to have reached a high level of fidelity about 200 years ago. Looking at this data statistically, what does it reveal?

Chronological chart of Great Comets and major comets, 1670 to present. Great Comets are marked with a yellow dot and all comets are displayed relative to their spheres of visibility – north, south or both. Image via T. Reyes/ Harvard University/ Space.com.

On average, every five years, one can expect to see a major comet visible from the Earth. However, the variability around that average is also about five years (one standard deviation).

This means that, on average, a major comet arrives every five to 10 years.

Sometimes the visitations are clustered. A prime example is the years 1910 and 1911, when four major comets crossed the sky.

The data also reveal that Great Comets arrive on average every 20 years. The variability is 10 years, as represented by a standard deviation around the average. So truly Great Comets may be visible from Earth every 20 to 30 years. Some centuries might have two or three (1800s) while others, four or more (1900s).

Great Comet of 1861, also known as C/1861 J1 or comet Tebbutt. Beyond this date, astrophotography began to capture Great Comets and major comets. Illustration via E. Weiß/ Bilderatlas der Sternenwelt.

Statistically, accounting for comet activity over 250 years – 38 major comets – is pretty sparse data, but one can see in the plot a historic trend. It is possible that if data could reveal a leaning towards one hemisphere, it could be an indicator that the Oort Cloud north or south of the ecliptic plane was affected by some object, e.g. a passing star. There is no indication of this in the records.

Does it answer the question? Has the Northern Hemisphere missed out on Great Comets?

There is certainly a recent trend towards the Southern Hemisphere for Great Comets. The data reveal that the long-term trend for both the Southern and Northern Hemispheres is a Great Comet every 25 to 40 years.

But, if you discount Hale-Bopp, then the last Great Comet for the Northern Hemisphere was Comet West, 44 years ago. Even if you consider Hale-Bopp as great, 23 years have passed.

It would seem that the north is statistically ready to receive its next Great Comet. Bring it on!

Comet Hale-Bopp with its prominent dust (white) and plasma (blue) tails. Photo taken from Linz, Austria. Image via E. Kolmhofer, H. Raab/ Johannes-Kepler-Observatory.

Bottom line: The Southern Hemisphere has had two Great Comets in this century: McNaught in 2007 and Lovejoy in 2011. But what about the Northern Hemisphere? Our last widely seen comet was Hale-Bopp in 1996-97. Comet West in 1976 was probably our last Great Comet. We’re due for one!

Read more and see charts: How to see Comet NEOWISE

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2PJeNPz

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire