The European Space Agency (ESA) and NASA released the first images from the Solar Orbiter (SolO) this week (July 16, 2020), and the images are – as expected – dazzlingly beautiful. They are the closest images taken of the sun so far. Launched on February 10 of this year, SolO’s very elliptical orbit ultimately will carry it periodically closer to the sun than the innermost planet, Mercury. Those very close perihelions – or closest points to the sun – will take several years to achieve, after gravity boosts from Earth and Venus. Meanwhile, in late May and June 2020, SolO swept closer to the sun than Venus, the sun’s second planet, coming within 47 million miles (77 million km) and capturing detail never seen before, including miniature solar flares that the scientists are referring to as campfires.

Solar Orbiter’s elliptical orbit will ultimately carry it closer to the sun than Mercury, or to within 26 million miles (42 million km) from the sun’s surface, or about 0.28 Earth’s distance. Animation via Phoenix7777/ Wikimedia Commons.

The features – in the sun’s outer atmosphere, or corona – are only as wide across as 250 miles (400 km). That’s in contrast to the sun’s diameter of 865,370 miles (1.4 million km). The scientists described the features as:

… a multitude of small flaring loops, erupting bright spots and dark, moving fibrils.

Solar Orbiter captured them in a series of views acquired by several remote-sensing instruments on the spacecraft, between May 30 and June 21, when the craft was roughly halfway between the Earth and the sun – closer to the sun than any other solar telescope has ever been before.

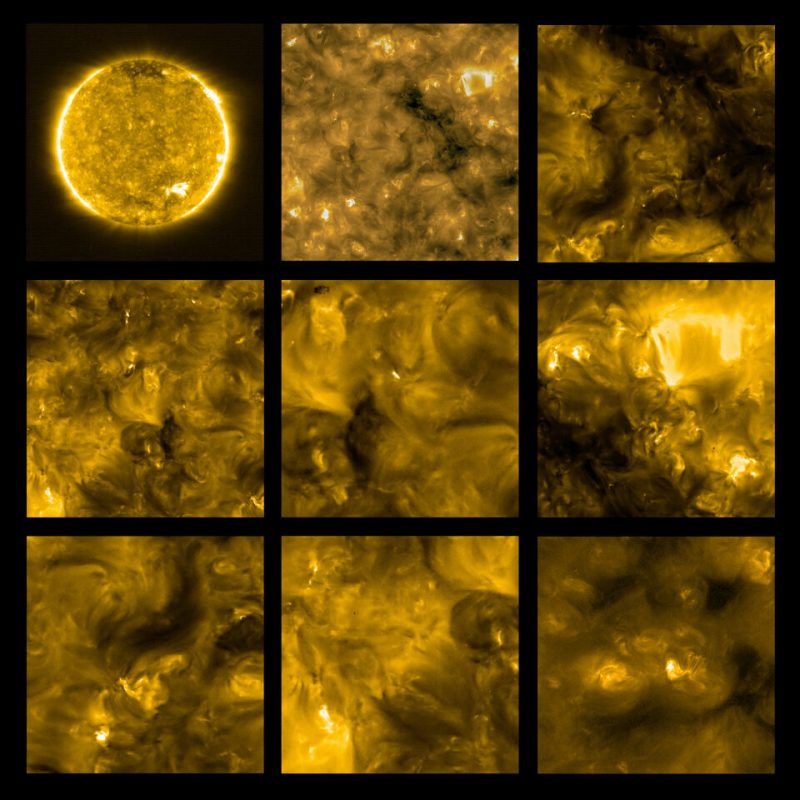

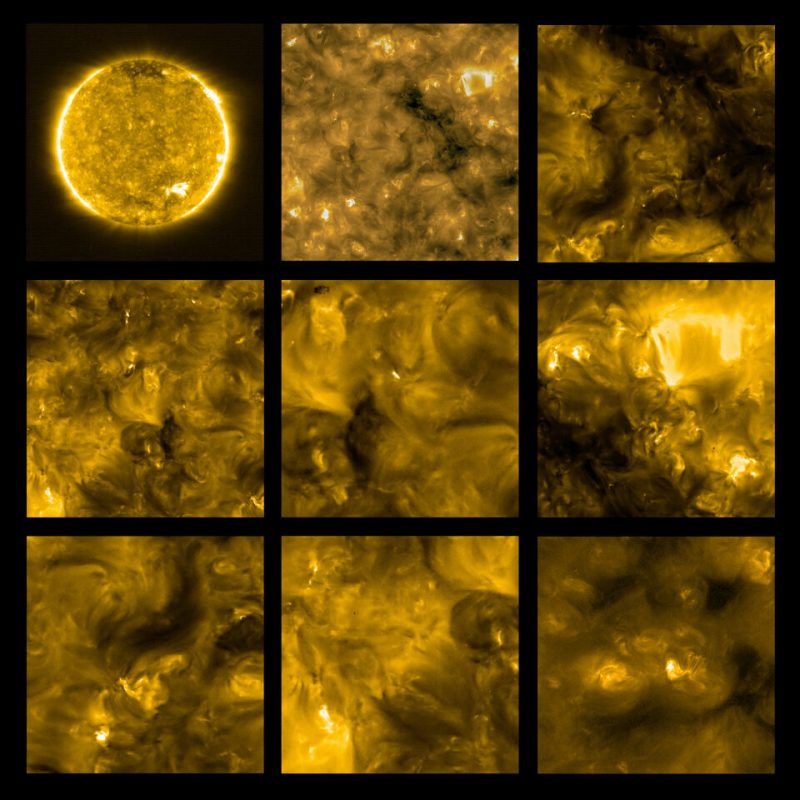

The Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI) on ESA’s Solar Orbiter spacecraft took these images on May 30, 2020. They show the sun’s appearance in the extreme ultraviolet region of the electromagnetic spectrum. Images at this wavelength reveal the upper atmosphere of the sun, the corona, with a temperature of around 1 million degrees Fahrenheit (600,000 degrees Celsius). EUI takes full disk images (top left) using the Full Sun Imager (FSI) telescope, as well as high resolution images using the HRIEUV telescope. Image via ESA.

The scientists compared the campfires to solar flares, which are short-lived eruptions on the sun associated with sunspots and times of high solar activity. There are few flares or spots on the sun now; we’re at a low point in the 11-year solar cycle. When they do occur, solar flares can cause electromagnetic disturbances on Earth, affecting communications satellites and electrical power grids.

The campfires seen by Solar Orbiter, on the other hand, are only a millionth or a billionth the size of solar flares.

However, these features on the sun may affect our local star. Scientists said the campfires might be contributing to the high temperatures of the sun’s corona. The high temperature of the corona – the wispy outer atmosphere of the sun that becomes visible during total solar eclipses – has long been a mystery. The temperature of the corona is more than a million degrees F (600,000 degrees C). That’s much hotter – mysteriously hotter – than the temperature at the sun’s visible surface, which is around 10,000 degrees F (5,500 degrees C).

Why do temperatures soar as you go farther from the center of the sun? That’s one question scientists have long wanted to answer.

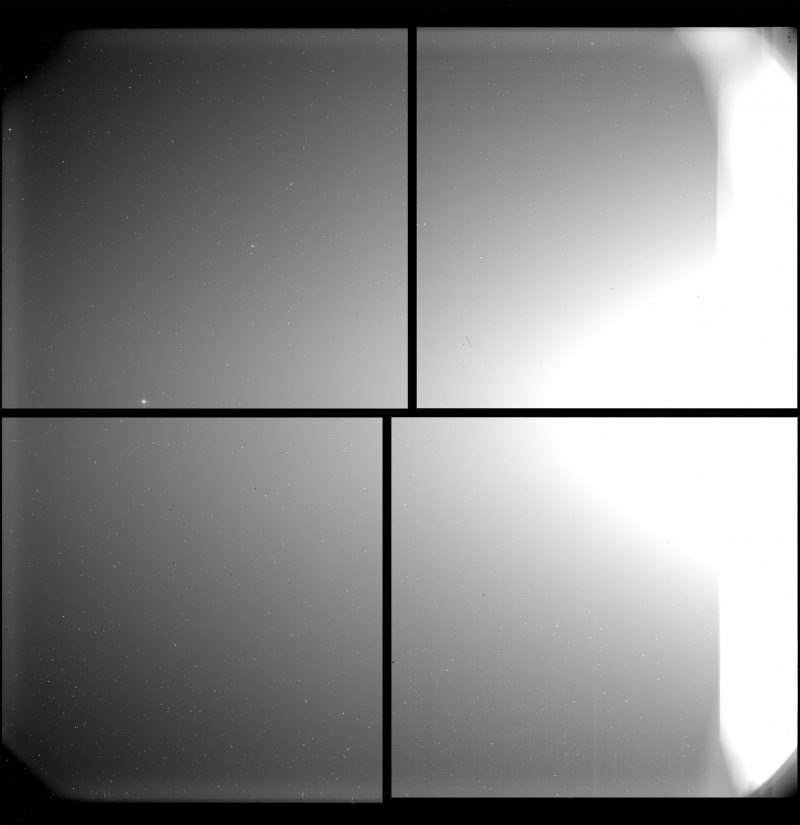

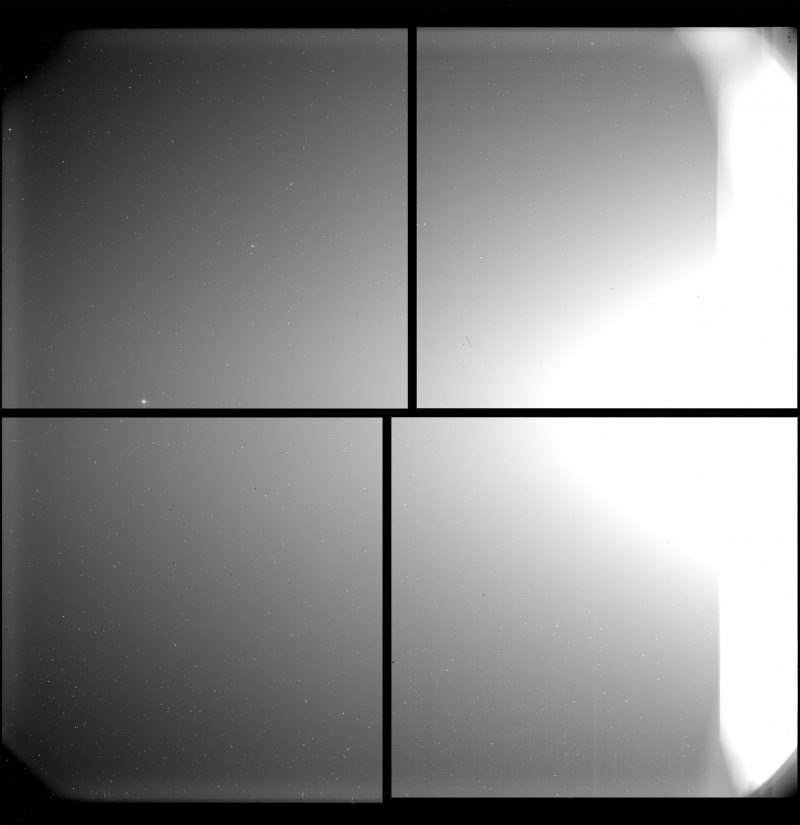

This mosaic is the 1st-light image from the SoloHI telescope. What you’re seeing here is light scattered by electrons in the solar wind. In this view, the sun is to the right of the frame, its light blocked by a series of baffles. The partial ellipse visible on the right is the zodiacal light – what we on Earth sometimes call the false dawn – created by sunlight reflecting off the dust particles that are orbiting the sun. Along the lower edge of the upper left tile, you can see a small dot: the planet Mercury. Image via NASA/ ESA Solar Orbiter.

In addition, the scientists said, the campfire features might be linked to the origin of the solar wind, a stream of charged particles released mostly from the sun’s corona, expanding from the sun and streaming past the planets to some three times Pluto’s distance. You might think of our solar system as a family of planets, but it’s also possible to think of it as a heliosphere, a bubble-like region surrounding the sun created by the solar wind.

Our sun’s heliosphere ends where the interstellar medium – or space between the stars – begins. It’s Solar Orbiter’s job, in part, to explore the heliosphere, and to answer questions about how the sun creates and controls it.

SolO is an international collaboration between ESA and NASA. Over time, the spacecraft’s orbit will be tilted upward out of the plane of the ecliptic, to give it a better view of the sun’s north and south poles. The SolO mission is expected to carry out 22 orbits in 10 years.

Here’s an image from a different instrument aboad Solar Orbiter, called the Metis coronograph. It blocks out the dazzling light from the solar surface, bringing the fainter corona into view. The green images here show what’s seen in visible light, and the red images show what’s seen in ultraviolet light. The scientists said these images (acquired closer to the sun than any before) showed “unprecedented temporal coverage and spatial resolution. These images reveal the two bright equatorial streamers and fainter polar regions that are characteristic of the solar corona during times of minimal magnetic activity.” Image via NASA/ ESA Solar Orbiter.

Bottom line: Solar Orbiter’s new views – released by NASA and ESA on July 16, 2020 – are the closest images of the sun taken so far.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/3eJPQhy

The European Space Agency (ESA) and NASA released the first images from the Solar Orbiter (SolO) this week (July 16, 2020), and the images are – as expected – dazzlingly beautiful. They are the closest images taken of the sun so far. Launched on February 10 of this year, SolO’s very elliptical orbit ultimately will carry it periodically closer to the sun than the innermost planet, Mercury. Those very close perihelions – or closest points to the sun – will take several years to achieve, after gravity boosts from Earth and Venus. Meanwhile, in late May and June 2020, SolO swept closer to the sun than Venus, the sun’s second planet, coming within 47 million miles (77 million km) and capturing detail never seen before, including miniature solar flares that the scientists are referring to as campfires.

Solar Orbiter’s elliptical orbit will ultimately carry it closer to the sun than Mercury, or to within 26 million miles (42 million km) from the sun’s surface, or about 0.28 Earth’s distance. Animation via Phoenix7777/ Wikimedia Commons.

The features – in the sun’s outer atmosphere, or corona – are only as wide across as 250 miles (400 km). That’s in contrast to the sun’s diameter of 865,370 miles (1.4 million km). The scientists described the features as:

… a multitude of small flaring loops, erupting bright spots and dark, moving fibrils.

Solar Orbiter captured them in a series of views acquired by several remote-sensing instruments on the spacecraft, between May 30 and June 21, when the craft was roughly halfway between the Earth and the sun – closer to the sun than any other solar telescope has ever been before.

The Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI) on ESA’s Solar Orbiter spacecraft took these images on May 30, 2020. They show the sun’s appearance in the extreme ultraviolet region of the electromagnetic spectrum. Images at this wavelength reveal the upper atmosphere of the sun, the corona, with a temperature of around 1 million degrees Fahrenheit (600,000 degrees Celsius). EUI takes full disk images (top left) using the Full Sun Imager (FSI) telescope, as well as high resolution images using the HRIEUV telescope. Image via ESA.

The scientists compared the campfires to solar flares, which are short-lived eruptions on the sun associated with sunspots and times of high solar activity. There are few flares or spots on the sun now; we’re at a low point in the 11-year solar cycle. When they do occur, solar flares can cause electromagnetic disturbances on Earth, affecting communications satellites and electrical power grids.

The campfires seen by Solar Orbiter, on the other hand, are only a millionth or a billionth the size of solar flares.

However, these features on the sun may affect our local star. Scientists said the campfires might be contributing to the high temperatures of the sun’s corona. The high temperature of the corona – the wispy outer atmosphere of the sun that becomes visible during total solar eclipses – has long been a mystery. The temperature of the corona is more than a million degrees F (600,000 degrees C). That’s much hotter – mysteriously hotter – than the temperature at the sun’s visible surface, which is around 10,000 degrees F (5,500 degrees C).

Why do temperatures soar as you go farther from the center of the sun? That’s one question scientists have long wanted to answer.

This mosaic is the 1st-light image from the SoloHI telescope. What you’re seeing here is light scattered by electrons in the solar wind. In this view, the sun is to the right of the frame, its light blocked by a series of baffles. The partial ellipse visible on the right is the zodiacal light – what we on Earth sometimes call the false dawn – created by sunlight reflecting off the dust particles that are orbiting the sun. Along the lower edge of the upper left tile, you can see a small dot: the planet Mercury. Image via NASA/ ESA Solar Orbiter.

In addition, the scientists said, the campfire features might be linked to the origin of the solar wind, a stream of charged particles released mostly from the sun’s corona, expanding from the sun and streaming past the planets to some three times Pluto’s distance. You might think of our solar system as a family of planets, but it’s also possible to think of it as a heliosphere, a bubble-like region surrounding the sun created by the solar wind.

Our sun’s heliosphere ends where the interstellar medium – or space between the stars – begins. It’s Solar Orbiter’s job, in part, to explore the heliosphere, and to answer questions about how the sun creates and controls it.

SolO is an international collaboration between ESA and NASA. Over time, the spacecraft’s orbit will be tilted upward out of the plane of the ecliptic, to give it a better view of the sun’s north and south poles. The SolO mission is expected to carry out 22 orbits in 10 years.

Here’s an image from a different instrument aboad Solar Orbiter, called the Metis coronograph. It blocks out the dazzling light from the solar surface, bringing the fainter corona into view. The green images here show what’s seen in visible light, and the red images show what’s seen in ultraviolet light. The scientists said these images (acquired closer to the sun than any before) showed “unprecedented temporal coverage and spatial resolution. These images reveal the two bright equatorial streamers and fainter polar regions that are characteristic of the solar corona during times of minimal magnetic activity.” Image via NASA/ ESA Solar Orbiter.

Bottom line: Solar Orbiter’s new views – released by NASA and ESA on July 16, 2020 – are the closest images of the sun taken so far.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/3eJPQhy

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire