Composite image of Jupiter and its 4 Galilean moons. From left to right the moons are Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto. The Galileo spacecraft obtained the images to make this composite in 1996. Image via NASA Photojournal.

Even though Jupiter is way out in the outer solar system, you can still see its four largest moons, often called the Galilean moons to honour the Italian astronomer Galileo, who discovered and confirmed them in 1610. If you have binoculars or a telescope, it’s actually fairly easy to see these moons whenever Jupiter is visible.

They may only look like tiny star-like pinpricks of light, but you can observe them all on or near the same plane as they cross – or transit – in front of Jupiter.

Going from closest to Jupiter to the outermost, their order is Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto.

Jupiter and its four Galilean moons as seen through a small telescope. Image via Jean B./ Astronomy.

Fernando Roquel Torres in Caguas, Puerto Rico, captured Jupiter, its Great Red Spot and all 4 of its largest moons – the Galilean satellites – at Jupiter’s 2017 opposition.

Writing at SkyandTelescope.com in June last year, Bob King said:

Etched in my brain cells is an image of a sharp, gleaming disk striped with two dark belts and accompanied by four star-like moons through my 2.4-inch refractor in the winter of 1966. A 6-inch reflector will make you privy to nearly all of the planet’s secrets …

When magnified at 150× or higher [the four Galilean moons] lose their star-like appearance and show disks that range in size from 1.0″ to 1.7″ (current opposition). Europa’s the smallest and Ganymede largest.

Ganymede also casts the largest shadow on the planet’s cloud tops when it transits in front of Jupiter. Shadow transits are visible at least once a week with ‘double transits’ – two moons casting shadows simultaneously – occurring once or twice a month. Ganymede’s shadow looks like a bullet hole, while little Europa’s more resembles a pinprick. Moons also fade away and then reappear over several minutes when they enter and exit Jupiter’s shadow during eclipse. Or a moon may be occulted by the Jovian disk and hover at the planet’s edge like a pearl before fading from sight.

View at EarthSky Community Photos. | Beautiful shot of Earth’s moon – plus Jupiter and its 4 largest moons – on May 20, 2019, via Asthadi Setyawan in Malang, East Java, Indonesia. Thank you, Asthadi!

Like with most moons and planets, the Galilean moons orbit Jupiter around its equator. We do see their orbits almost exactly edge-on, but, as with so much in astronomy, there’s a cycle for viewing the edge-on-ness of Jupiter’s moons. This particular cycle is six years long. That is, every six years, we view Jupiter’s equator – and the moons orbiting above its equator – at the most edge-on.

And that’s why, in 2015, we were able to view a number of mutual events (eclipses and shadow transits) involving Jupiter’s moons, through telescopes.

Starting in late 2016, Jupiter’s axis began tilting enough toward the sun and Earth so that the outermost of the four moons, Callisto, had not been passing in front of Jupiter or behind Jupiter, as seen from our vantage point. This will continue for a period of about three years, during which time Callisto is perpetually visible to those with telescopes, alternately swinging above and below Jupiter as seen from Earth.

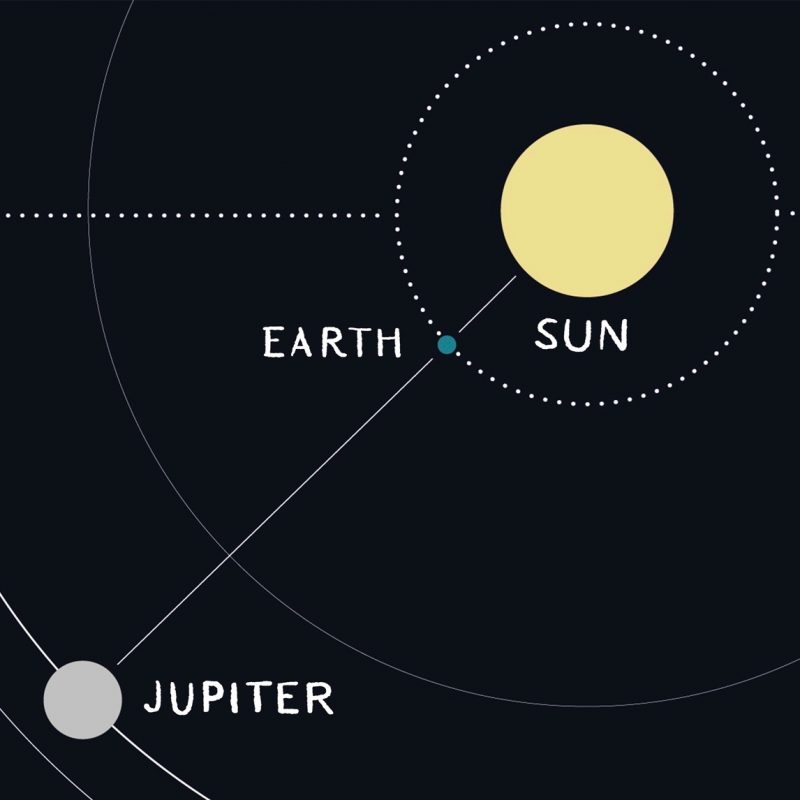

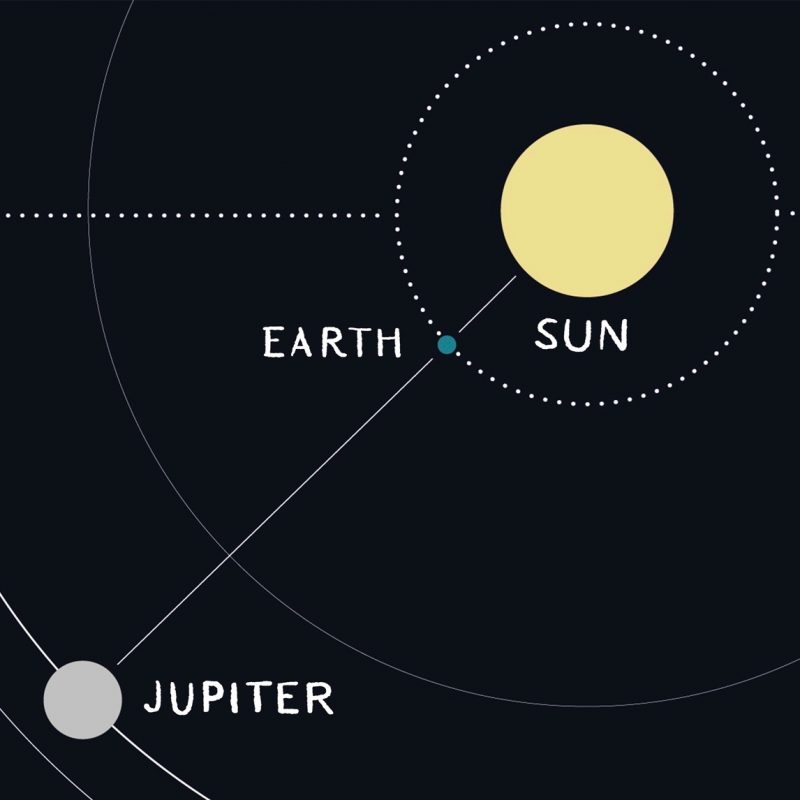

Opposition – when Earth is directly between Jupiter and the sun – is the best time to observe the largest planet and its four Galilean moons. This year, it is July 13-14. Image via EarthSky.

The next eclipse series of Callisto, whereby this moon actually passes behind Jupiter, started on November 9, 2019, and ends on August 22, 2022, to present a total of 61 eclipses. After that, the next eclipse series will occur from May 29, 2025, to June 7, 2028, to feature 67 eclipses.

Right now, Jupiter is at opposition, when Earth is directly between Jupiter and the sun. Opposition is the middle of the best time of the year to see a planet, since that’s when the planet is up and viewable all night and is generally closest for the year. This year, Jupiter is at peak opposition from July 13-14, 2020. So if you get a chance, grab some binoculars or a small telescope and go see Jupiter’s Galilean moons with your own eyes!

Click here for recommended sky almanacs; they can tell you Jupiter’s rising time in your sky.

Bottom line: How to see Jupiter’s four largest moons.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2LhWrFE

Composite image of Jupiter and its 4 Galilean moons. From left to right the moons are Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto. The Galileo spacecraft obtained the images to make this composite in 1996. Image via NASA Photojournal.

Even though Jupiter is way out in the outer solar system, you can still see its four largest moons, often called the Galilean moons to honour the Italian astronomer Galileo, who discovered and confirmed them in 1610. If you have binoculars or a telescope, it’s actually fairly easy to see these moons whenever Jupiter is visible.

They may only look like tiny star-like pinpricks of light, but you can observe them all on or near the same plane as they cross – or transit – in front of Jupiter.

Going from closest to Jupiter to the outermost, their order is Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto.

Jupiter and its four Galilean moons as seen through a small telescope. Image via Jean B./ Astronomy.

Fernando Roquel Torres in Caguas, Puerto Rico, captured Jupiter, its Great Red Spot and all 4 of its largest moons – the Galilean satellites – at Jupiter’s 2017 opposition.

Writing at SkyandTelescope.com in June last year, Bob King said:

Etched in my brain cells is an image of a sharp, gleaming disk striped with two dark belts and accompanied by four star-like moons through my 2.4-inch refractor in the winter of 1966. A 6-inch reflector will make you privy to nearly all of the planet’s secrets …

When magnified at 150× or higher [the four Galilean moons] lose their star-like appearance and show disks that range in size from 1.0″ to 1.7″ (current opposition). Europa’s the smallest and Ganymede largest.

Ganymede also casts the largest shadow on the planet’s cloud tops when it transits in front of Jupiter. Shadow transits are visible at least once a week with ‘double transits’ – two moons casting shadows simultaneously – occurring once or twice a month. Ganymede’s shadow looks like a bullet hole, while little Europa’s more resembles a pinprick. Moons also fade away and then reappear over several minutes when they enter and exit Jupiter’s shadow during eclipse. Or a moon may be occulted by the Jovian disk and hover at the planet’s edge like a pearl before fading from sight.

View at EarthSky Community Photos. | Beautiful shot of Earth’s moon – plus Jupiter and its 4 largest moons – on May 20, 2019, via Asthadi Setyawan in Malang, East Java, Indonesia. Thank you, Asthadi!

Like with most moons and planets, the Galilean moons orbit Jupiter around its equator. We do see their orbits almost exactly edge-on, but, as with so much in astronomy, there’s a cycle for viewing the edge-on-ness of Jupiter’s moons. This particular cycle is six years long. That is, every six years, we view Jupiter’s equator – and the moons orbiting above its equator – at the most edge-on.

And that’s why, in 2015, we were able to view a number of mutual events (eclipses and shadow transits) involving Jupiter’s moons, through telescopes.

Starting in late 2016, Jupiter’s axis began tilting enough toward the sun and Earth so that the outermost of the four moons, Callisto, had not been passing in front of Jupiter or behind Jupiter, as seen from our vantage point. This will continue for a period of about three years, during which time Callisto is perpetually visible to those with telescopes, alternately swinging above and below Jupiter as seen from Earth.

Opposition – when Earth is directly between Jupiter and the sun – is the best time to observe the largest planet and its four Galilean moons. This year, it is July 13-14. Image via EarthSky.

The next eclipse series of Callisto, whereby this moon actually passes behind Jupiter, started on November 9, 2019, and ends on August 22, 2022, to present a total of 61 eclipses. After that, the next eclipse series will occur from May 29, 2025, to June 7, 2028, to feature 67 eclipses.

Right now, Jupiter is at opposition, when Earth is directly between Jupiter and the sun. Opposition is the middle of the best time of the year to see a planet, since that’s when the planet is up and viewable all night and is generally closest for the year. This year, Jupiter is at peak opposition from July 13-14, 2020. So if you get a chance, grab some binoculars or a small telescope and go see Jupiter’s Galilean moons with your own eyes!

Click here for recommended sky almanacs; they can tell you Jupiter’s rising time in your sky.

Bottom line: How to see Jupiter’s four largest moons.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2LhWrFE

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire