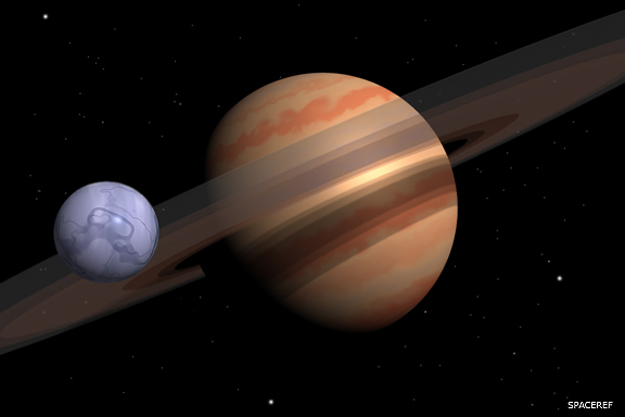

Artist’s concept of a habitable exomoon orbiting a distant exoplanet similar to Saturn. Astronomers have now discovered what may be 6 more exomoons orbiting exoplanets ranging from 200 to 3,000 light-years away. There are hundreds of moons in our own solar system, and some of them have subsurface water oceans. How many similar ocean moons may be out there? Image via SpaceRef/ Astrobiology Web.

Our solar system is filled with hundreds of moons, many more moons than planets. But what about distant solar systems? We now know of well over 4,000 confirmed exoplanets – or planets orbiting distant stars – 4,171 right now, to be exact. Yet there’ve been, so far, still only a few possible detections of exomoons. It makes sense, given that moons of planets tend to be smaller and thus more difficult to find than planets themselves. But now scientists at Western University in London, Ontario, Canada, have announced that they might have spotted six more exomoons!

The potentially exciting findings have been submitted in a new paper to the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, with a preprint version posted on arXiv on June 23, 2020.

The possible moons are not confirmed yet, but the results seem promising. As Paul Wiegert, co-author of the study, noted in a statement:

We know of thousands of exoplanets throughout our Milky Way galaxy, but we know of only a handful of exomoon candidates.

From the paper:

Here we explore eight systems from the Kepler data set to examine the exomoon hypothesis as an explanation for their transit timing variations, which we compare with the alternate hypothesis that the TTVs are caused by an non-transiting planet in the system. We find that the TTVs of six of these systems could be plausibly explained by an exomoon, the size of which would not be nominally detectable by Kepler. Though we also find that the TTVs could be equally well reproduced by the presence of a non-transiting planet in the system, the observations are nevertheless completely consistent with a existence of a dynamically stable moon small enough to fall below Kepler’s photometric threshold for transit detection, and these systems warrant further observation and analysis.

So where are these moons and how were they potentially found?

The moons are in data from the Kepler Space Telescope mission, which ended in 2018. The host planets range from about 200 to 3,000 light-years away, and were discovered by the transits that the planets made in front of their stars, which caused the star’s brightness to dim slightly and briefly. Most exoplanets are found using the transit method. But the moons are much smaller and dimmer, so they are very difficult to detect by any method. Wiegert said:

These exomoon candidates are so small that they can’t be seen from their own transits. Rather, their presence is given away by their gravitational influence on their parent planet.

The six moon candidates are (KOI) 268.01, Kepler 517b (KOI-303.01), Kepler 1000b (KOI-1888.01), Kepler 409b (KOI-1925.01), Kepler 1326b (KOI-2728.01) and Kepler 1442b (KOI-3220.01). KOI refers to Kepler Object of Interest.

So how might these moons reveal themselves?

Usually, the transit of a planet occurs precisely at regular timed intervals, the same as how planets orbit our own sun. But sometimes, that precise timing is actually variable. This means that the gravity of some other body, another planet or a moon, must be affecting it. These variations are called transit timing variations (TTVs). The results fit with what would be expected of exomoons, but could still possibly be explained by other planets in these systems instead. As Fox explained:

Because exoplanets are more massive than exomoons, most TTVs observed to date have been linked to the influence of other exoplanets. But now we’ve uncovered six Kepler exoplanet systems whose TTVs are equally well explained by exomoons as by exoplanets. That’s why we’re calling them exomoon ‘candidates’ at this point as they still need follow-up confirmation.

TTVs were also found for two other exoplanets, KOI-1503.01 and KOI-1980.01, but those are thought to be caused by other planets in the systems instead of moons and were ruled out.

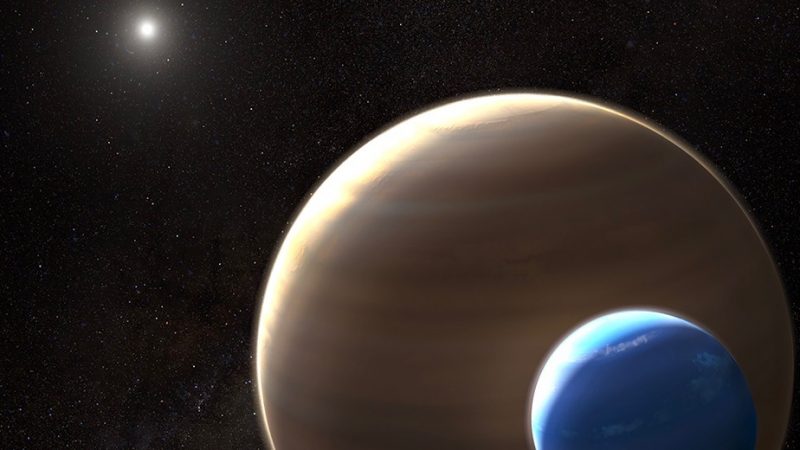

Artist’s concept of the possible huge exomoon orbiting the exoplanet Kepler-1625b, found by the Hubble Space Telescope in 2018. Image via HubbleSite.

That confirmation may have to wait a while, however, since current telescopes can’t do it; it will require telescopes that are being planned and designed, but not built yet. Fox said:

We can say these six new systems are completely consistent with exomoons: their masses and orbits are such that they would be stable; they would be small enough that their own transits wouldn’t be seen; and they reproduce the pattern of TTVs seen throughout the entire Kepler data set. But we don’t have the technology to confirm them by imaging them directly. That will have to wait for further advancements.

It is exciting to contemplate what kinds of alien exomoons are out there. Just in our own solar system, there is a huge variety of these smaller worlds, from gray, cratered and moon-like, to Io, which kind of looks like a pizza and has the most active volcanoes of any object in the solar system, to ocean worlds like Europa, Enceladus and others. The icy moons with subsurface oceans are especially appealing, since they could be habitable by earthly standards. There are several of them in our solar system alone, so how many more might be out there? What kind of life might exist on such worlds? Chris Fox, who made the discoveries, said:

Our own solar system contains hundreds of moons. If moons are prolific around other stars, too, it greatly increases the potential places where life might be supported, and where humankind might one day venture.

Chris Fox at Western University, who discovered the possible new exomoons. Image via CBC.

Fox makes a very good point. Since our own solar system has hundreds of moons orbiting six out of the eight planets, is it not reasonable that many of the planets in other solar systems would also have their own moons? And as we are now discovering, a good number of the moons in our solar system are indeed potentially habitable, with their subsurface water oceans.

In 2018, Fox also discovered Kepler-159d, an exoplanet about the size of Saturn, which orbits its star in only 88 days.

In 2014, another possible exomoon, dubbed MOA-2011-BLG-262 exoplanet-exomoon system, was discovered, where the moon would be less massive than Earth and the planet would be more massive than Jupiter. In 2018, the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) found what may be a huge exomoon orbiting the gas giant planet Kepler-1625b. It’s also still not confirmed yet, but if real, is about the size of Neptune! If the new findings from Western University are any indication – and confirmed – then there may many more exomoon discoveries to look forward to.

Bottom line: Astronomers examining data from the Kepler Space Telescope appear to have discovered six more exomoons. Although the result awaits confirmation, it has the potential to be a big step forward in understanding distant solar systems.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2ZvIc4z

Artist’s concept of a habitable exomoon orbiting a distant exoplanet similar to Saturn. Astronomers have now discovered what may be 6 more exomoons orbiting exoplanets ranging from 200 to 3,000 light-years away. There are hundreds of moons in our own solar system, and some of them have subsurface water oceans. How many similar ocean moons may be out there? Image via SpaceRef/ Astrobiology Web.

Our solar system is filled with hundreds of moons, many more moons than planets. But what about distant solar systems? We now know of well over 4,000 confirmed exoplanets – or planets orbiting distant stars – 4,171 right now, to be exact. Yet there’ve been, so far, still only a few possible detections of exomoons. It makes sense, given that moons of planets tend to be smaller and thus more difficult to find than planets themselves. But now scientists at Western University in London, Ontario, Canada, have announced that they might have spotted six more exomoons!

The potentially exciting findings have been submitted in a new paper to the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, with a preprint version posted on arXiv on June 23, 2020.

The possible moons are not confirmed yet, but the results seem promising. As Paul Wiegert, co-author of the study, noted in a statement:

We know of thousands of exoplanets throughout our Milky Way galaxy, but we know of only a handful of exomoon candidates.

From the paper:

Here we explore eight systems from the Kepler data set to examine the exomoon hypothesis as an explanation for their transit timing variations, which we compare with the alternate hypothesis that the TTVs are caused by an non-transiting planet in the system. We find that the TTVs of six of these systems could be plausibly explained by an exomoon, the size of which would not be nominally detectable by Kepler. Though we also find that the TTVs could be equally well reproduced by the presence of a non-transiting planet in the system, the observations are nevertheless completely consistent with a existence of a dynamically stable moon small enough to fall below Kepler’s photometric threshold for transit detection, and these systems warrant further observation and analysis.

So where are these moons and how were they potentially found?

The moons are in data from the Kepler Space Telescope mission, which ended in 2018. The host planets range from about 200 to 3,000 light-years away, and were discovered by the transits that the planets made in front of their stars, which caused the star’s brightness to dim slightly and briefly. Most exoplanets are found using the transit method. But the moons are much smaller and dimmer, so they are very difficult to detect by any method. Wiegert said:

These exomoon candidates are so small that they can’t be seen from their own transits. Rather, their presence is given away by their gravitational influence on their parent planet.

The six moon candidates are (KOI) 268.01, Kepler 517b (KOI-303.01), Kepler 1000b (KOI-1888.01), Kepler 409b (KOI-1925.01), Kepler 1326b (KOI-2728.01) and Kepler 1442b (KOI-3220.01). KOI refers to Kepler Object of Interest.

So how might these moons reveal themselves?

Usually, the transit of a planet occurs precisely at regular timed intervals, the same as how planets orbit our own sun. But sometimes, that precise timing is actually variable. This means that the gravity of some other body, another planet or a moon, must be affecting it. These variations are called transit timing variations (TTVs). The results fit with what would be expected of exomoons, but could still possibly be explained by other planets in these systems instead. As Fox explained:

Because exoplanets are more massive than exomoons, most TTVs observed to date have been linked to the influence of other exoplanets. But now we’ve uncovered six Kepler exoplanet systems whose TTVs are equally well explained by exomoons as by exoplanets. That’s why we’re calling them exomoon ‘candidates’ at this point as they still need follow-up confirmation.

TTVs were also found for two other exoplanets, KOI-1503.01 and KOI-1980.01, but those are thought to be caused by other planets in the systems instead of moons and were ruled out.

Artist’s concept of the possible huge exomoon orbiting the exoplanet Kepler-1625b, found by the Hubble Space Telescope in 2018. Image via HubbleSite.

That confirmation may have to wait a while, however, since current telescopes can’t do it; it will require telescopes that are being planned and designed, but not built yet. Fox said:

We can say these six new systems are completely consistent with exomoons: their masses and orbits are such that they would be stable; they would be small enough that their own transits wouldn’t be seen; and they reproduce the pattern of TTVs seen throughout the entire Kepler data set. But we don’t have the technology to confirm them by imaging them directly. That will have to wait for further advancements.

It is exciting to contemplate what kinds of alien exomoons are out there. Just in our own solar system, there is a huge variety of these smaller worlds, from gray, cratered and moon-like, to Io, which kind of looks like a pizza and has the most active volcanoes of any object in the solar system, to ocean worlds like Europa, Enceladus and others. The icy moons with subsurface oceans are especially appealing, since they could be habitable by earthly standards. There are several of them in our solar system alone, so how many more might be out there? What kind of life might exist on such worlds? Chris Fox, who made the discoveries, said:

Our own solar system contains hundreds of moons. If moons are prolific around other stars, too, it greatly increases the potential places where life might be supported, and where humankind might one day venture.

Chris Fox at Western University, who discovered the possible new exomoons. Image via CBC.

Fox makes a very good point. Since our own solar system has hundreds of moons orbiting six out of the eight planets, is it not reasonable that many of the planets in other solar systems would also have their own moons? And as we are now discovering, a good number of the moons in our solar system are indeed potentially habitable, with their subsurface water oceans.

In 2018, Fox also discovered Kepler-159d, an exoplanet about the size of Saturn, which orbits its star in only 88 days.

In 2014, another possible exomoon, dubbed MOA-2011-BLG-262 exoplanet-exomoon system, was discovered, where the moon would be less massive than Earth and the planet would be more massive than Jupiter. In 2018, the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) found what may be a huge exomoon orbiting the gas giant planet Kepler-1625b. It’s also still not confirmed yet, but if real, is about the size of Neptune! If the new findings from Western University are any indication – and confirmed – then there may many more exomoon discoveries to look forward to.

Bottom line: Astronomers examining data from the Kepler Space Telescope appear to have discovered six more exomoons. Although the result awaits confirmation, it has the potential to be a big step forward in understanding distant solar systems.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2ZvIc4z

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire