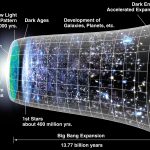

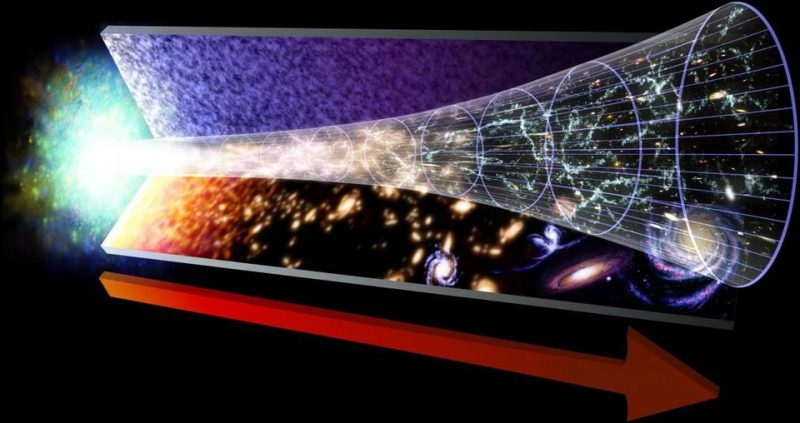

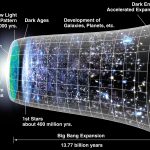

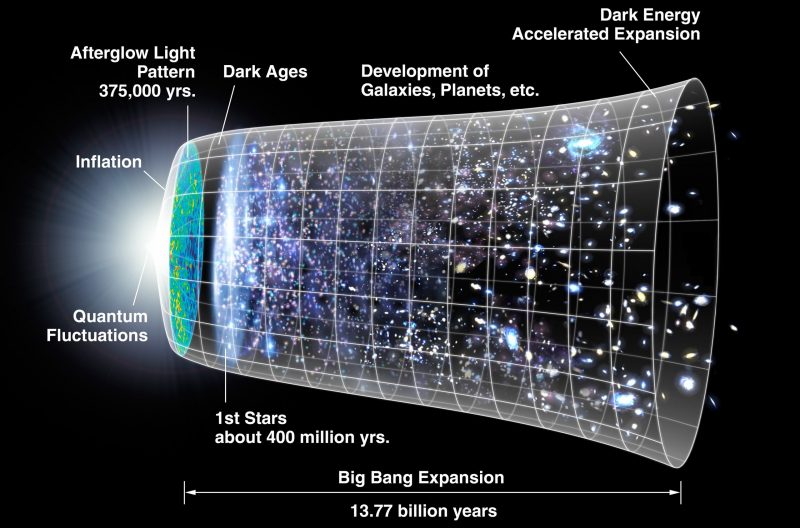

Timeline of the universe, from Big Bang to present day. The far left depicts the earliest moment we can probe so far, when a period of cosmic inflation produced a burst of exponential growth in the universe. For the next several billion years, the expansion of the universe gradually slowed down as the matter in the universe pulled on itself via gravity. More recently, the expansion has begun to speed up again as the repulsive effects of dark energy have come to dominate the expansion of the universe. Read more about this image from NASA.

You’ve probably heard of the Big Bang as the event that gave rise to our universe. You might know most cosmologists believe it occurred some 13.8 billion years ago. It’s hard to fathom that, at the moment of the Big Bang, all of the energy in the universe – some of which would later become galaxies, stars, planets and human beings – was concentrated into a tiny point, smaller than the nucleus of an atom. And it’s not just matter that was born in the Big Bang. In the view of modern cosmologists, matter and space and time all began when that microscopic point suddenly expanded violently and exponentially.

The first atoms are thought to have formed when the universe was around 400,000 years old. Before that, the universe was simply too hot and too energetic to let atomic nuclei capture electrons. The first stars sparkled into life, cosmologists believe, about 250 million years after the Big Bang, and the first galaxies shortly after that.

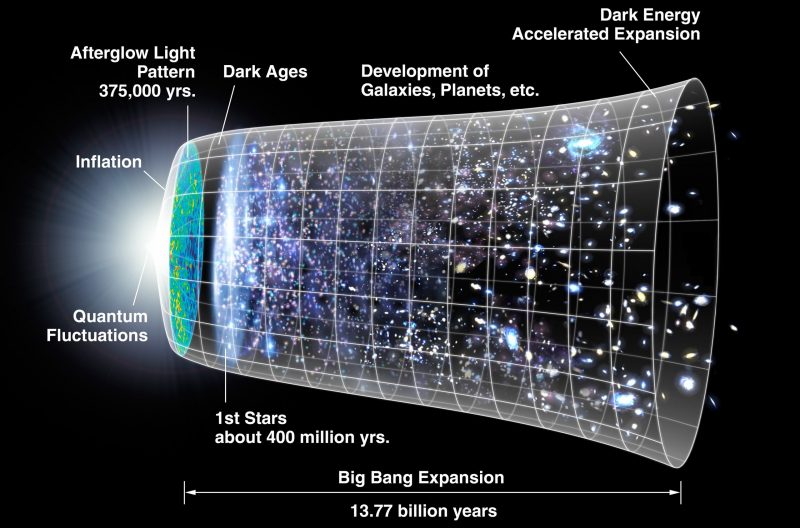

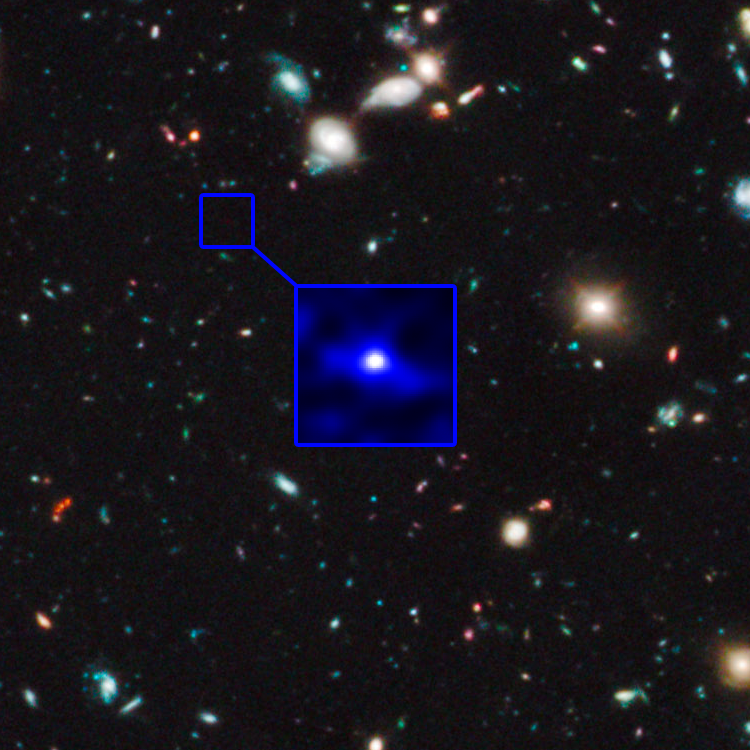

The Hubble Space Telescope captured this image of an exceedingly distant galaxy called UDFj-39546284. This object has a redshift of z~10, meaning that it existed some 480 million years after the Big Bang. Image via NASA/ ESA/ Garth Illingworth/ Rychard Bouwens/ the HUDF09 Team/ Wikimedia Commons.

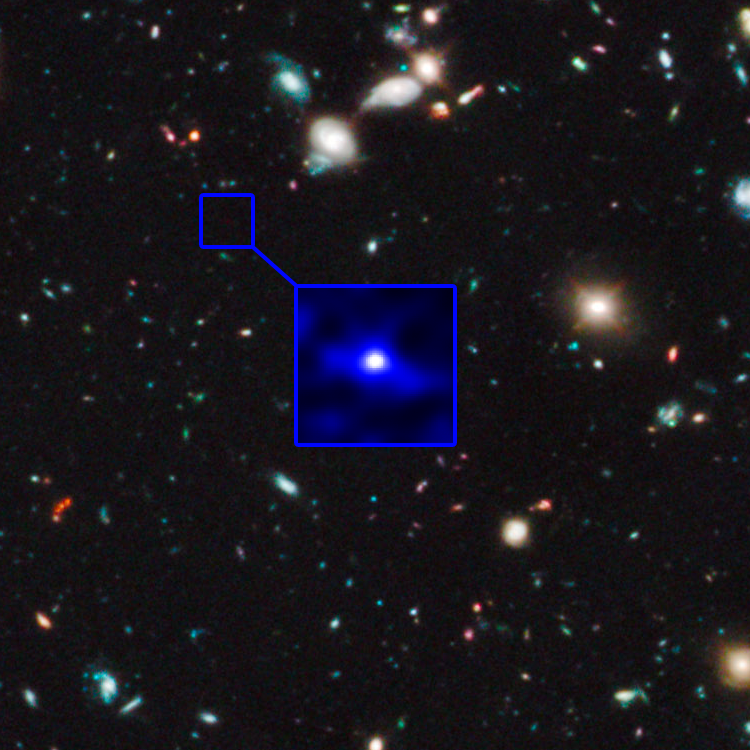

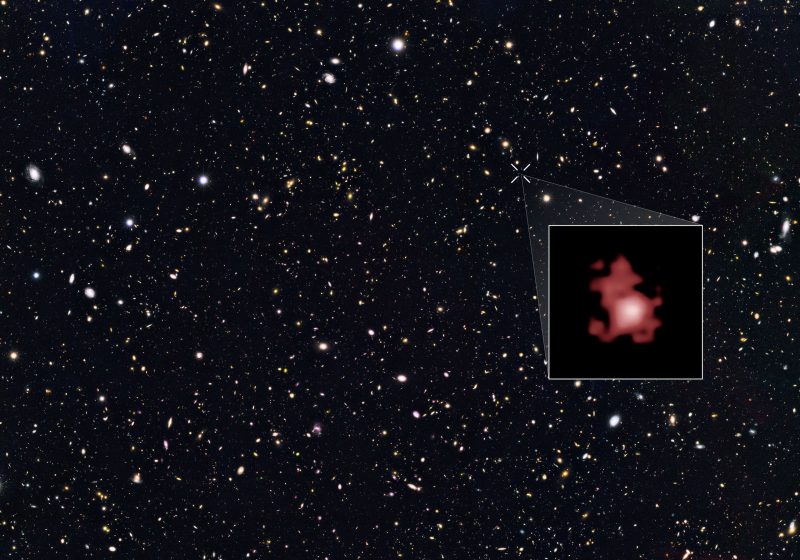

Here’s another exceedingly distant (and therefore old) object, captured by the Hubble Space Telescope in 2016. Galaxy GN-z11, shown in the inset, is seen as it was 13.4 billion years in the past, just 400 million years after the Big Bang, when the universe was only 3% of its current age. The galaxy is ablaze with bright, young, blue stars, but looks red in this image because its light has been stretched to longer spectral wavelengths by the expansion of the universe. Image via NASA/ ESA/ P. Oesch/ G. Brammer/ P. van Dokkum / G. Illingworth/ Hubblesite.

The Big Bang refers to a theory. How could it be otherwise? The current version of Big Bang theory – the one used most by modern cosmologists – is called the Lambda-CDM model. It postulates that our universe began at a specific instant, expanded to be flat (i.e. has zero curvature) and is made up of 5% baryons (i.e. the matter that makes up everything we see – galaxies, stars, planets, people), 27% cold dark matter (hence the “CDM” of the theory’s name) and 68% dark energy.

The Lambda-CDM model further states that the universe is expanding at a rate referred to as Lambda (the Greek letter) and is governed by the principles of Einstein’s General Relativity. The Lambda-CDM model has been spectacularly successful at explaining what we observe in the universe. It makes predictions repeatedly confirmed by observation. But it is not without problems; as with all scientific theories, the Lambda-CDM model continues to evolve.

Now let’s pause a moment, so that we might draw a distinction between the appearance of all that energy in the Big Bang and its sudden expansion. In that sense, the Big Bang was not the event that caused our universe. Rather, it was the event that gave birth to the universe. Why is this distinction important? It’s important because, although science has been able to establish a history of the universe right back to when that tiny point suddenly created our entire cosmos, what preceded it, the reason for that tiny point of energy being there in the first place, is unknown, and may forever be unknowable.

The Big Bang is the theory we have constructed for how the universe we see around us came to be. It does not attempt to answer the most common question we humans ask about the origin of the cosmos: why? And this question likely cannot be answered, because, by definition, whatever caused the appearance of that tiny point of energy, containing the seeds of everything that would ever be, was not of this universe.

Therefore, whatever caused the universe left no evidence of its existence for us to study, no clue as to what it was. It is also likely that, being something completely outside the universe, we would, in any event, be unable to comprehend it. The laws of physics, of motion, of gravity, of electromagnetism, of thermodynamics, simply did not apply at the moment of the universe’s birth because they did not yet exist: they certainly cannot describe the presence and origin of that tiny seed.

That has not stopped cosmologists, who study the history and large-scale structure of the universe, from trying to answer such questions, of course, because that’s the nature of science. Some people attribute the existence of that tiny seed of energy to a god, as humans have invented gods throughout the ages to explain things they could not understand, but there is absolutely no reason for believing that idea, other than perhaps wishful thinking. There is certainly nothing we observe in the history of the universe to suggest that its origin was anything other than a natural event, even if we cannot comprehend it. On the other hand, there’s nothing to suggest the origin of our universe was not caused by a god, either.

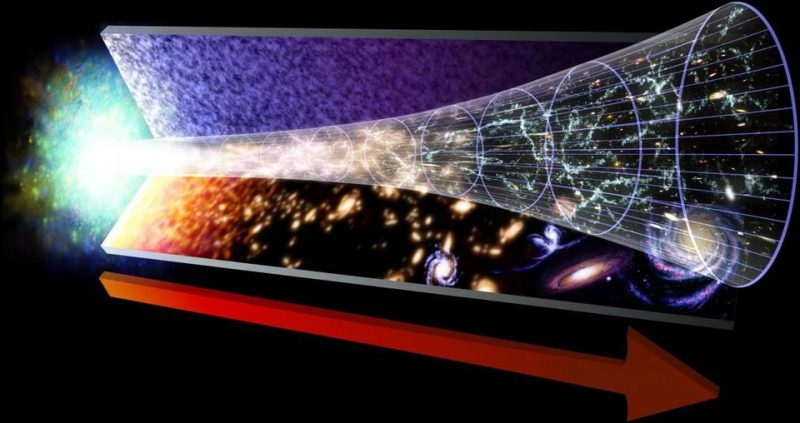

Artist’s representation of the history of the universe and the arrow of time. Big Bang theory implies that time moves in a single direction. However, scientists have discovered that, at the quantum level, in the realm of sub-atomic particles, many processes are what we call “time-reversible”: there is no distinction between past, present and future. Image via Forbes.

The Lambda-CDM model also states that time itself started at the Big Bang, on the basis that if there are no events, there is no time to measure. This raises an old philosophical question of whether time is a human construct or exists independently of us. This question has taxed some of the greatest philosophers and scientists but has never been answered satisfactorily. Still, if we define time as the period which elapses between events, it is fair to say that time started with the Big Bang.

Another common question is: what happened before the Big Bang? That question can have no meaning if we accept the Big Bang was the start of the universe’s clock: it’s like asking what’s north of the North Pole. This answer, while demonstrating the irrationality of asking about a “before”, is not, however, satisfactory to humans accustomed to cause and effect: we reason that if the Big Bang was an event which was the result of something, some change, some instability, there had to be a before. However, that is only in our experience, in the world we are familiar with, where an event always has a cause, and has absolutely no bearing on the universe coming into being because, again, the laws of physics, which in our world govern cause and effect, simply did not exist. And as if to underline how superficial, how biased, our perception of time, scientists have discovered that at the quantum level, in the realm of sub-atomic particles, many processes are what we call “time-reversible:” there is simply no distinction between past, present and future.

It’s also important to realize that, at the moment of the Big Bang, there was no space and there were no dimensions. Space itself, and the dimensions within that space, came into being at that moment, as the bubble of energy expanded. This means that, contrary to what most people believe, the Big Bang was not an explosion. Think of anything exploding, and it explodes into a space, an area, which was there already. But in the case of the Big Bang, there was no preexisting space for an explosion to occur in.

A related question which is often asked is: where did the Big Bang happen? Those who ask this believe you can point at a location in the sky and say, “it happened there.” But the answer to the question is that the Big Bang happened everywhere. It’s just that everywhere existed within that tiny bubble of infinitely-hot expanding energy, because there was literally nothing outside it – no space, no dimensions, nothing. Watch any documentary about the Big Bang and it will show it as a huge explosion, viewed from outside. But such a viewpoint is impossible – there was no “outside”. One cannot, of course, blame filmmakers for this: there is simply no way to portray the Big Bang visually in a way which is scientifically accurate. It’s doubtful we even have the vocabulary to describe it, let alone portray it.

Space itself is believed to have been born in the Big Bang. Artist’s concept via Christine Daniloff/ MIT/ ESA/ Hubble/ NASA/ Phys.org.

If you find it difficult to get your head around the idea of the Big Bang happening everywhere, with no outside, at a particular moment when time started some 13.8 billion years ago, you are not alone. The human brain is not well equipped for dealing with such concepts. Even when Edwin Hubble, in the 1920s, demonstrated that the universe is expanding in all directions, and therefore, if you wind the clock back far enough, all of the universe must have occupied one tiny point, the idea that the universe had a definite beginning, and was therefore not infinitely old, was simply unacceptable to many. Among these who rejected the Big Bang were prominent scientists: Einstein himself denied the idea of an expanding universe. Another scientist who rejected the notion of a universe of finite age was famed British astronomer Sir Fred Hoyle, the man who, more than any other individual, unlocked the mystery of how stars work.

Hoyle gave a series of lectures on BBC radio in the late 1940s and early ’50s, and, on one of these – on the BBC’s Third Programme broadcast on March 28, 1949 – he poured derision on the idea of the universe beginning at a fixed point in time and referred to cosmologists’ description of the event as a “Big Bang.” Unfortunately for Hoyle, the name stuck, and we’ve called this event the Big Bang ever since.

Fred Hoyle. He coined the term “Big Bang” to describe the event in which our universe was born, while explaining a rival theory, the Steady State theory, in a radio talk in 1949 Image via Britannica.com.

Image via ExploringCosmos006.

Hoyle never accepted that the universe had a beginning, even until his death at the age at 86 in 2001. He became the leading proponent of Steady State Theory, which says that the universe has no beginning or end: it constantly regenerates itself, with new matter condensing out of nothing.

Hoyle’s blunt intransigence – he was from Yorkshire, an English county said to be famed for the plain-speaking and directness of its inhabitants – was not lessened by the subsequent success of Big Bang theory, not even after it successfully predicted the abundancies of light elements, such as hydrogen, helium and lithium, in the universe. Nor did he come to accept the Big Bang when Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson discovered the predicted Cosmic Microwave Background, the Big Bang’s dying echo, in 1964. Steady State Theory had predicted none of these things, nor did it have explanations for them.

Nor was Hoyle fazed when Alan Guth constructed the theory of Cosmological Inflation as a refinement to existing Big Bang theory in 1979. Inflation explains why the universe is the same temperature everywhere and is “flat”, amongst other features of the universe not hitherto explained, although it has yet to be observationally completely verified.

Even the year before he died, Hoyle published yet another scientific paper on Steady State theory, but by this time his ideas were completely rejected by most cosmologists. And, sadly for him, they were also rejected by the overwhelming observational evidence for the Big Bang. Steady State Theory just does not work, makes false predictions and is contradicted by what we actually see in the universe. As a hypothesis – lacking supporting observational evidence, it was that rather than a theory, although commonly referred to as such – it essentially died with Hoyle.

Today, the Lambda-CDM Big Bang model is the only theory that makes any testable predictions and that is supported by observations.

Most cosmologists today believe we know the history of the universe back to 10-21 seconds after the Big Bang – that’s 0.0000000000000000000001 seconds. The painstaking piecing together of this history over the last 50 years, although lacking in fine detail as it undoubtedly is, represents humans’ greatest intellectual achievement, our species’ crowning glory. It has been achieved through an unparalleled synthesis of astronomy, astrophysics, cosmology, particle physics, chemistry and other sciences.

But science will not rest until we can push our theories back even further in time, to that exact moment when the universe came into being.

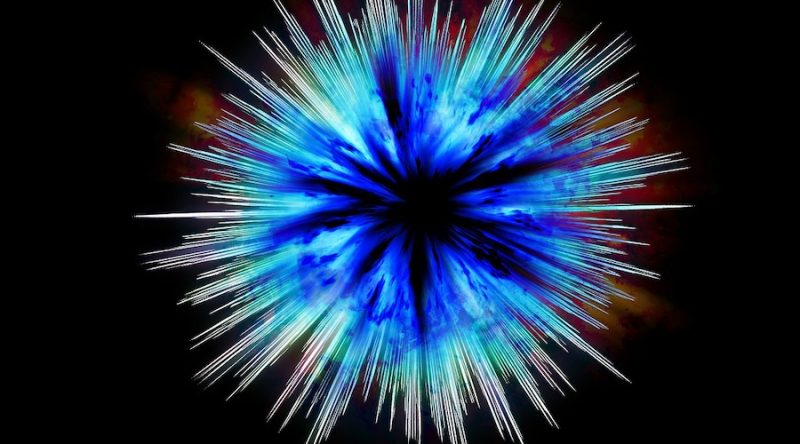

Artist’s concept of the Big Bang, the event now believed to have marked our universe’s birth. If we looked far enough back in time, could we witness the birth of the universe?

Bottom line: At the moment of the Big Bang, all of the energy in the universe – some of which would later become galaxies, stars, planets and human beings – was concentrated into a tiny point, smaller than the nucleus of an atom. And it’s not just matter that was born in the Big Bang. In the view of modern cosmologists, matter and space and time all began when that microscopic point suddenly expanded violently and exponentially.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/3hfGfkR

Timeline of the universe, from Big Bang to present day. The far left depicts the earliest moment we can probe so far, when a period of cosmic inflation produced a burst of exponential growth in the universe. For the next several billion years, the expansion of the universe gradually slowed down as the matter in the universe pulled on itself via gravity. More recently, the expansion has begun to speed up again as the repulsive effects of dark energy have come to dominate the expansion of the universe. Read more about this image from NASA.

You’ve probably heard of the Big Bang as the event that gave rise to our universe. You might know most cosmologists believe it occurred some 13.8 billion years ago. It’s hard to fathom that, at the moment of the Big Bang, all of the energy in the universe – some of which would later become galaxies, stars, planets and human beings – was concentrated into a tiny point, smaller than the nucleus of an atom. And it’s not just matter that was born in the Big Bang. In the view of modern cosmologists, matter and space and time all began when that microscopic point suddenly expanded violently and exponentially.

The first atoms are thought to have formed when the universe was around 400,000 years old. Before that, the universe was simply too hot and too energetic to let atomic nuclei capture electrons. The first stars sparkled into life, cosmologists believe, about 250 million years after the Big Bang, and the first galaxies shortly after that.

The Hubble Space Telescope captured this image of an exceedingly distant galaxy called UDFj-39546284. This object has a redshift of z~10, meaning that it existed some 480 million years after the Big Bang. Image via NASA/ ESA/ Garth Illingworth/ Rychard Bouwens/ the HUDF09 Team/ Wikimedia Commons.

Here’s another exceedingly distant (and therefore old) object, captured by the Hubble Space Telescope in 2016. Galaxy GN-z11, shown in the inset, is seen as it was 13.4 billion years in the past, just 400 million years after the Big Bang, when the universe was only 3% of its current age. The galaxy is ablaze with bright, young, blue stars, but looks red in this image because its light has been stretched to longer spectral wavelengths by the expansion of the universe. Image via NASA/ ESA/ P. Oesch/ G. Brammer/ P. van Dokkum / G. Illingworth/ Hubblesite.

The Big Bang refers to a theory. How could it be otherwise? The current version of Big Bang theory – the one used most by modern cosmologists – is called the Lambda-CDM model. It postulates that our universe began at a specific instant, expanded to be flat (i.e. has zero curvature) and is made up of 5% baryons (i.e. the matter that makes up everything we see – galaxies, stars, planets, people), 27% cold dark matter (hence the “CDM” of the theory’s name) and 68% dark energy.

The Lambda-CDM model further states that the universe is expanding at a rate referred to as Lambda (the Greek letter) and is governed by the principles of Einstein’s General Relativity. The Lambda-CDM model has been spectacularly successful at explaining what we observe in the universe. It makes predictions repeatedly confirmed by observation. But it is not without problems; as with all scientific theories, the Lambda-CDM model continues to evolve.

Now let’s pause a moment, so that we might draw a distinction between the appearance of all that energy in the Big Bang and its sudden expansion. In that sense, the Big Bang was not the event that caused our universe. Rather, it was the event that gave birth to the universe. Why is this distinction important? It’s important because, although science has been able to establish a history of the universe right back to when that tiny point suddenly created our entire cosmos, what preceded it, the reason for that tiny point of energy being there in the first place, is unknown, and may forever be unknowable.

The Big Bang is the theory we have constructed for how the universe we see around us came to be. It does not attempt to answer the most common question we humans ask about the origin of the cosmos: why? And this question likely cannot be answered, because, by definition, whatever caused the appearance of that tiny point of energy, containing the seeds of everything that would ever be, was not of this universe.

Therefore, whatever caused the universe left no evidence of its existence for us to study, no clue as to what it was. It is also likely that, being something completely outside the universe, we would, in any event, be unable to comprehend it. The laws of physics, of motion, of gravity, of electromagnetism, of thermodynamics, simply did not apply at the moment of the universe’s birth because they did not yet exist: they certainly cannot describe the presence and origin of that tiny seed.

That has not stopped cosmologists, who study the history and large-scale structure of the universe, from trying to answer such questions, of course, because that’s the nature of science. Some people attribute the existence of that tiny seed of energy to a god, as humans have invented gods throughout the ages to explain things they could not understand, but there is absolutely no reason for believing that idea, other than perhaps wishful thinking. There is certainly nothing we observe in the history of the universe to suggest that its origin was anything other than a natural event, even if we cannot comprehend it. On the other hand, there’s nothing to suggest the origin of our universe was not caused by a god, either.

Artist’s representation of the history of the universe and the arrow of time. Big Bang theory implies that time moves in a single direction. However, scientists have discovered that, at the quantum level, in the realm of sub-atomic particles, many processes are what we call “time-reversible”: there is no distinction between past, present and future. Image via Forbes.

The Lambda-CDM model also states that time itself started at the Big Bang, on the basis that if there are no events, there is no time to measure. This raises an old philosophical question of whether time is a human construct or exists independently of us. This question has taxed some of the greatest philosophers and scientists but has never been answered satisfactorily. Still, if we define time as the period which elapses between events, it is fair to say that time started with the Big Bang.

Another common question is: what happened before the Big Bang? That question can have no meaning if we accept the Big Bang was the start of the universe’s clock: it’s like asking what’s north of the North Pole. This answer, while demonstrating the irrationality of asking about a “before”, is not, however, satisfactory to humans accustomed to cause and effect: we reason that if the Big Bang was an event which was the result of something, some change, some instability, there had to be a before. However, that is only in our experience, in the world we are familiar with, where an event always has a cause, and has absolutely no bearing on the universe coming into being because, again, the laws of physics, which in our world govern cause and effect, simply did not exist. And as if to underline how superficial, how biased, our perception of time, scientists have discovered that at the quantum level, in the realm of sub-atomic particles, many processes are what we call “time-reversible:” there is simply no distinction between past, present and future.

It’s also important to realize that, at the moment of the Big Bang, there was no space and there were no dimensions. Space itself, and the dimensions within that space, came into being at that moment, as the bubble of energy expanded. This means that, contrary to what most people believe, the Big Bang was not an explosion. Think of anything exploding, and it explodes into a space, an area, which was there already. But in the case of the Big Bang, there was no preexisting space for an explosion to occur in.

A related question which is often asked is: where did the Big Bang happen? Those who ask this believe you can point at a location in the sky and say, “it happened there.” But the answer to the question is that the Big Bang happened everywhere. It’s just that everywhere existed within that tiny bubble of infinitely-hot expanding energy, because there was literally nothing outside it – no space, no dimensions, nothing. Watch any documentary about the Big Bang and it will show it as a huge explosion, viewed from outside. But such a viewpoint is impossible – there was no “outside”. One cannot, of course, blame filmmakers for this: there is simply no way to portray the Big Bang visually in a way which is scientifically accurate. It’s doubtful we even have the vocabulary to describe it, let alone portray it.

Space itself is believed to have been born in the Big Bang. Artist’s concept via Christine Daniloff/ MIT/ ESA/ Hubble/ NASA/ Phys.org.

If you find it difficult to get your head around the idea of the Big Bang happening everywhere, with no outside, at a particular moment when time started some 13.8 billion years ago, you are not alone. The human brain is not well equipped for dealing with such concepts. Even when Edwin Hubble, in the 1920s, demonstrated that the universe is expanding in all directions, and therefore, if you wind the clock back far enough, all of the universe must have occupied one tiny point, the idea that the universe had a definite beginning, and was therefore not infinitely old, was simply unacceptable to many. Among these who rejected the Big Bang were prominent scientists: Einstein himself denied the idea of an expanding universe. Another scientist who rejected the notion of a universe of finite age was famed British astronomer Sir Fred Hoyle, the man who, more than any other individual, unlocked the mystery of how stars work.

Hoyle gave a series of lectures on BBC radio in the late 1940s and early ’50s, and, on one of these – on the BBC’s Third Programme broadcast on March 28, 1949 – he poured derision on the idea of the universe beginning at a fixed point in time and referred to cosmologists’ description of the event as a “Big Bang.” Unfortunately for Hoyle, the name stuck, and we’ve called this event the Big Bang ever since.

Fred Hoyle. He coined the term “Big Bang” to describe the event in which our universe was born, while explaining a rival theory, the Steady State theory, in a radio talk in 1949 Image via Britannica.com.

Image via ExploringCosmos006.

Hoyle never accepted that the universe had a beginning, even until his death at the age at 86 in 2001. He became the leading proponent of Steady State Theory, which says that the universe has no beginning or end: it constantly regenerates itself, with new matter condensing out of nothing.

Hoyle’s blunt intransigence – he was from Yorkshire, an English county said to be famed for the plain-speaking and directness of its inhabitants – was not lessened by the subsequent success of Big Bang theory, not even after it successfully predicted the abundancies of light elements, such as hydrogen, helium and lithium, in the universe. Nor did he come to accept the Big Bang when Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson discovered the predicted Cosmic Microwave Background, the Big Bang’s dying echo, in 1964. Steady State Theory had predicted none of these things, nor did it have explanations for them.

Nor was Hoyle fazed when Alan Guth constructed the theory of Cosmological Inflation as a refinement to existing Big Bang theory in 1979. Inflation explains why the universe is the same temperature everywhere and is “flat”, amongst other features of the universe not hitherto explained, although it has yet to be observationally completely verified.

Even the year before he died, Hoyle published yet another scientific paper on Steady State theory, but by this time his ideas were completely rejected by most cosmologists. And, sadly for him, they were also rejected by the overwhelming observational evidence for the Big Bang. Steady State Theory just does not work, makes false predictions and is contradicted by what we actually see in the universe. As a hypothesis – lacking supporting observational evidence, it was that rather than a theory, although commonly referred to as such – it essentially died with Hoyle.

Today, the Lambda-CDM Big Bang model is the only theory that makes any testable predictions and that is supported by observations.

Most cosmologists today believe we know the history of the universe back to 10-21 seconds after the Big Bang – that’s 0.0000000000000000000001 seconds. The painstaking piecing together of this history over the last 50 years, although lacking in fine detail as it undoubtedly is, represents humans’ greatest intellectual achievement, our species’ crowning glory. It has been achieved through an unparalleled synthesis of astronomy, astrophysics, cosmology, particle physics, chemistry and other sciences.

But science will not rest until we can push our theories back even further in time, to that exact moment when the universe came into being.

Artist’s concept of the Big Bang, the event now believed to have marked our universe’s birth. If we looked far enough back in time, could we witness the birth of the universe?

Bottom line: At the moment of the Big Bang, all of the energy in the universe – some of which would later become galaxies, stars, planets and human beings – was concentrated into a tiny point, smaller than the nucleus of an atom. And it’s not just matter that was born in the Big Bang. In the view of modern cosmologists, matter and space and time all began when that microscopic point suddenly expanded violently and exponentially.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/3hfGfkR

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire