The European Space Agency (ESA) announced on June 15, 2020, that its Solar Orbiter spacecraft – which sped into space this past February in a dramatic night launch – has made its first close approach to our star. It swept as close to the sun’s surface as about 50 million miles (77 million km), or about half the average distance between the sun and Earth. No images yet! The first ones are expected to be released in July. Meanwhile, the scientists say they will:

… test the spacecraft’s 10 science instruments, including the six telescopes on-board, which will acquire close-up images of the sun in unison for the first time.

Today is THE DAY! The day of Solar Orbiter's first perihelion. We are about 77 million km from the Sun's surface, half the distance between Earth and the Sun. No one has ever been closer with a camera to the beast. Read more: https://t.co/3MG3VUovZ7 pic.twitter.com/jG8uSAw2w2

— ESA's Solar Orbiter (@ESASolarOrbiter) June 15, 2020

Solar Orbiter Project Scientist Daniel Müller commented in a statement from ESA:

We have never taken pictures of the sun from a closer distance than this. There have been higher resolution close-ups, e.g. taken by the 4-meter Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope in Hawaii earlier this year. But from Earth, with the atmosphere between the telescope and the sun, you can only see a small part of the solar spectrum that you can see from space.

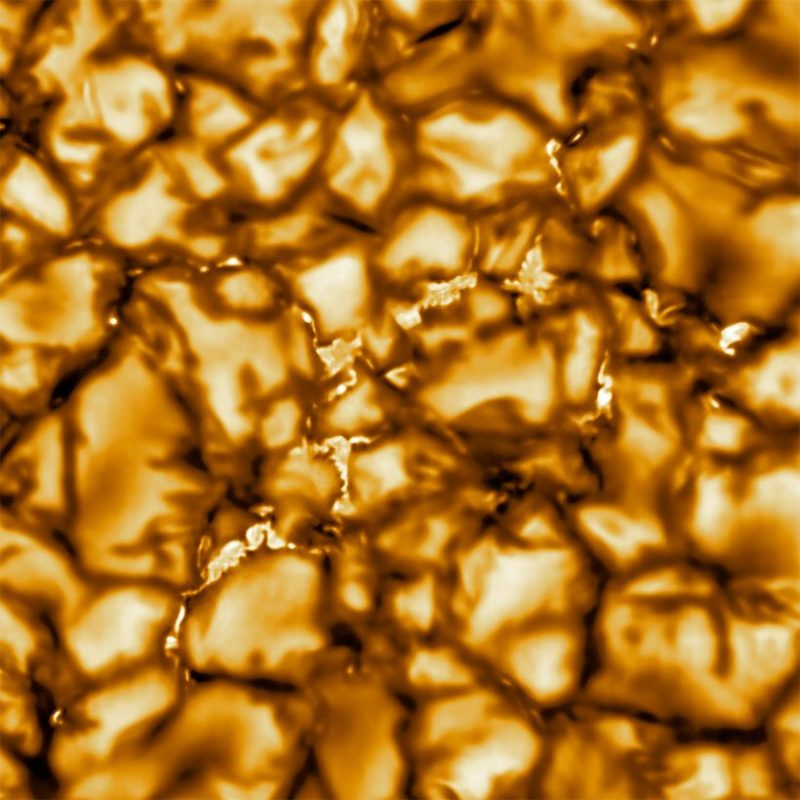

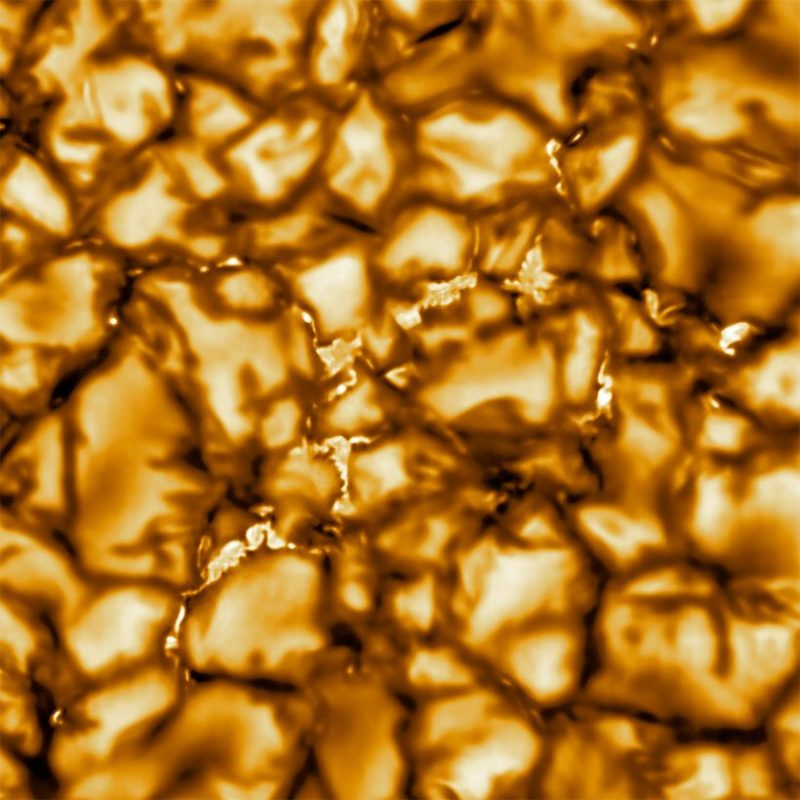

The 1st published image from the Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope in Hawaii. This telescope takes higher-resolution images than Solar Orbiter will, but it can see only a small part of the range of energy emitted by our sun. Image via NSO/ NSF/ AURA.

NASA’s Parker Solar Probe, launched in 2018, makes closer approaches, ESA pointed out. But that spacecraft doesn’t carry telescopes capable of looking directly at the sun. Daniel commented:

Our ultraviolet imaging telescopes have the same spatial resolution as those of NASA’s Solar Dynamic Observatory (SDO), which takes high-resolution images of the sun from an orbit close to Earth. Because we are currently at half the distance to the sun, our images have twice SDO’s resolution during this perihelion.

The sun today (June 15, 2020), via NASA SDO’s Atmospheric Imaging Assembly (AIA). This instrument provides full-disk observations of the sun’s chromosphere and corona in the ultraviolet. In contrast, at ultraviolet wavelengths, Solar Orbiter is expected to see the sun’s surface about twice as clearly as SDO when Solar Orbiter is at perihelion, or closest to the sun.

Solar Orbiter was launched on February 10 of this year. As of today (June 15), its commissioning phase is complete. Now the craft will commence its cruise phase, which will last until November 2021. The spacecraft will continue getting closer and closer to the sun. During the main science phase ahead, it’ll get as close as 26 million miles (42 million km) to the sun’s surface, which is closer than the innermost planet Mercury. ESA said:

The spacecraft will reach its next perihelion in early 2021. During the first close approach of the main science phase, in early 2022, it will get as close as 48 million km [about 30 million miles].

Solar Orbiter operators will then use the gravity of Venus to gradually shift the spacecraft’s orbit out of the ecliptic plane, in which the planets of the solar system orbit. These fly-by maneuvers will enable Solar Orbiter to look at the sun from higher latitudes and get the first ever proper view of its poles. Studying the activity in the polar regions will help the scientists to better understand the behavior of the sun’s magnetic field, which drives the creation of the solar wind that in turn affects the environment of the entire solar system.

Since the spacecraft is currently 134 million km [about 80 million miles] from Earth, it will take about a week for all perihelion images to be downloaded via ESA’s 35-meter deep-space antenna in Malargüe, Argentina. The science teams will then process the images before releasing them to the public in mid-July. The data from the in-situ instruments will become public later this year after a careful calibration of all individual sensors.

Daniel commented:

We have a 9-hour download window every day but we are already very far from Earth so the data rate is much lower than it was in the early weeks of the mission when we were still very close to Earth. In the later phases of the mission, it will occasionally take up to several months to download all the data because Solar Orbiter really is a deep space mission.

Artist’s concept of the European Space Agency’s sun-exploring Solar Orbiter. Launched this past February 9, 2020, the craft made its first close approach to the star on June 15, sweeping as close as about 50 million miles (77 million km), or about half Earth’s distance from the sun. Image via ESA.

Bottom line: Solar Orbiter swept as close as 50 million miles (77 million km) to our sun’s surface on June 15, 2020. New images are being downloaded now and are expected to be released in July. Over the next several years, Solar Orbiter will sweep even closer to our star – closer than the innermost planet Mercury – and obtain very clear images of its surface.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/3cYbCNy

The European Space Agency (ESA) announced on June 15, 2020, that its Solar Orbiter spacecraft – which sped into space this past February in a dramatic night launch – has made its first close approach to our star. It swept as close to the sun’s surface as about 50 million miles (77 million km), or about half the average distance between the sun and Earth. No images yet! The first ones are expected to be released in July. Meanwhile, the scientists say they will:

… test the spacecraft’s 10 science instruments, including the six telescopes on-board, which will acquire close-up images of the sun in unison for the first time.

Today is THE DAY! The day of Solar Orbiter's first perihelion. We are about 77 million km from the Sun's surface, half the distance between Earth and the Sun. No one has ever been closer with a camera to the beast. Read more: https://t.co/3MG3VUovZ7 pic.twitter.com/jG8uSAw2w2

— ESA's Solar Orbiter (@ESASolarOrbiter) June 15, 2020

Solar Orbiter Project Scientist Daniel Müller commented in a statement from ESA:

We have never taken pictures of the sun from a closer distance than this. There have been higher resolution close-ups, e.g. taken by the 4-meter Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope in Hawaii earlier this year. But from Earth, with the atmosphere between the telescope and the sun, you can only see a small part of the solar spectrum that you can see from space.

The 1st published image from the Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope in Hawaii. This telescope takes higher-resolution images than Solar Orbiter will, but it can see only a small part of the range of energy emitted by our sun. Image via NSO/ NSF/ AURA.

NASA’s Parker Solar Probe, launched in 2018, makes closer approaches, ESA pointed out. But that spacecraft doesn’t carry telescopes capable of looking directly at the sun. Daniel commented:

Our ultraviolet imaging telescopes have the same spatial resolution as those of NASA’s Solar Dynamic Observatory (SDO), which takes high-resolution images of the sun from an orbit close to Earth. Because we are currently at half the distance to the sun, our images have twice SDO’s resolution during this perihelion.

The sun today (June 15, 2020), via NASA SDO’s Atmospheric Imaging Assembly (AIA). This instrument provides full-disk observations of the sun’s chromosphere and corona in the ultraviolet. In contrast, at ultraviolet wavelengths, Solar Orbiter is expected to see the sun’s surface about twice as clearly as SDO when Solar Orbiter is at perihelion, or closest to the sun.

Solar Orbiter was launched on February 10 of this year. As of today (June 15), its commissioning phase is complete. Now the craft will commence its cruise phase, which will last until November 2021. The spacecraft will continue getting closer and closer to the sun. During the main science phase ahead, it’ll get as close as 26 million miles (42 million km) to the sun’s surface, which is closer than the innermost planet Mercury. ESA said:

The spacecraft will reach its next perihelion in early 2021. During the first close approach of the main science phase, in early 2022, it will get as close as 48 million km [about 30 million miles].

Solar Orbiter operators will then use the gravity of Venus to gradually shift the spacecraft’s orbit out of the ecliptic plane, in which the planets of the solar system orbit. These fly-by maneuvers will enable Solar Orbiter to look at the sun from higher latitudes and get the first ever proper view of its poles. Studying the activity in the polar regions will help the scientists to better understand the behavior of the sun’s magnetic field, which drives the creation of the solar wind that in turn affects the environment of the entire solar system.

Since the spacecraft is currently 134 million km [about 80 million miles] from Earth, it will take about a week for all perihelion images to be downloaded via ESA’s 35-meter deep-space antenna in Malargüe, Argentina. The science teams will then process the images before releasing them to the public in mid-July. The data from the in-situ instruments will become public later this year after a careful calibration of all individual sensors.

Daniel commented:

We have a 9-hour download window every day but we are already very far from Earth so the data rate is much lower than it was in the early weeks of the mission when we were still very close to Earth. In the later phases of the mission, it will occasionally take up to several months to download all the data because Solar Orbiter really is a deep space mission.

Artist’s concept of the European Space Agency’s sun-exploring Solar Orbiter. Launched this past February 9, 2020, the craft made its first close approach to the star on June 15, sweeping as close as about 50 million miles (77 million km), or about half Earth’s distance from the sun. Image via ESA.

Bottom line: Solar Orbiter swept as close as 50 million miles (77 million km) to our sun’s surface on June 15, 2020. New images are being downloaded now and are expected to be released in July. Over the next several years, Solar Orbiter will sweep even closer to our star – closer than the innermost planet Mercury – and obtain very clear images of its surface.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/3cYbCNy

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire