The first Earth Day in 1972 spurred other countries to support global environmental action. Image via Callista Images/Getty

By Maria Ivanova, University of Massachusetts Boston

The first Earth Day protests, which took place on April 22, 1970 brought 20 million Americans – 10% of the U.S. population at the time – into the streets. Recognizing the power of this growing movement, President Richard Nixon and Congress responded by creating the Environmental Protection Agency and enacting a wave of laws, including the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act and the Endangered Species Act.

But Earth Day’s impact extended far beyond the United States. A cadre of professionals in the U.S. State Department understood that environmental problems didn’t stop at national borders, and set up mechanisms for addressing them jointly with other countries.

For scholars like me who study global governance, the challenge of getting nations to act together is a central issue. In my view, without the first Earth Day, global action against problems like trade in endangered species, stratospheric ozone depletion and climate change would have taken much longer – or might never have happened at all.

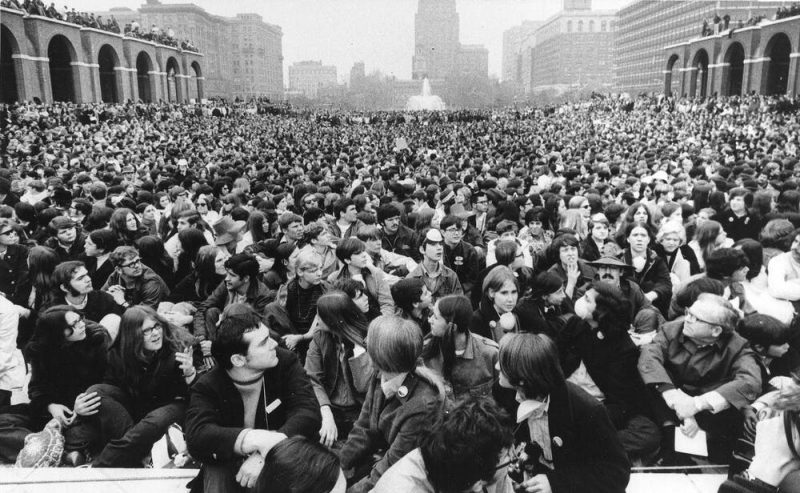

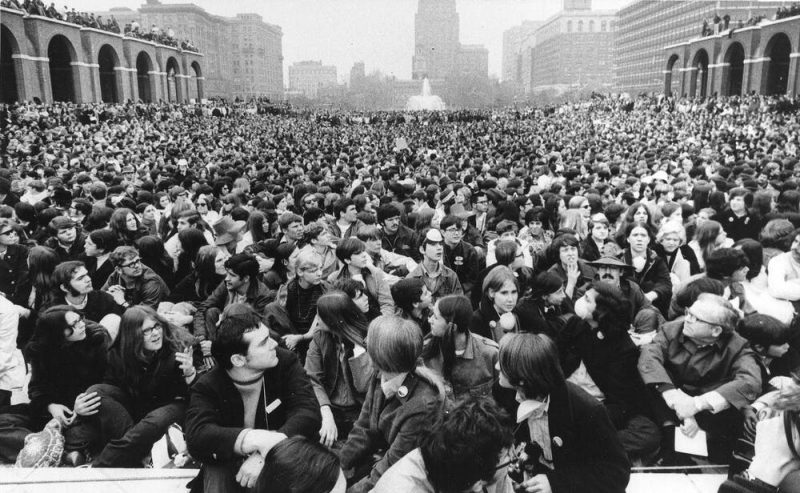

An estimated 7,000 demonstrators in Philadelphia on Earth Day, April 22, 1970. Image via AP Photo

Alarms across the world

In 1970 governments around the world were contending with transborder pollution challenges. For example, sulfur and nitrogen oxides emitted from coal-fired power plants in the United Kingdom traveled hundreds of miles on northerly winds, then returned to earth in northern Europe as acid rain, fog and snow. This process was killing lakes and forests in Germany and Sweden.

Realizing that solutions would only be effective through common effort, countries convened the first global conference on the environment in Stockholm from June 5-16, 1972. Representatives of 113 governments attended and adopted the Stockholm Declaration on the Human Environment, which asserts that humans have a fundamental right to an environment that permits a life of dignity and well-being. They also passed a resolution to create a new international environmental institution.

Contrary to its posture today, the United States was an ardent proponent of the conference. The U.S. delegation advanced a series of actions, including a moratorium on commercial whaling, a convention to regulate ocean dumping and the creation of a World Heritage Trust to preserve wilderness areas and scenic natural landmarks.

President Nixon issued a statement when the conference concluded, observing that…

for the first time in history, the nations of the world sat down together to seek better understanding of each other’s environmental problems and to explore opportunities for positive action, individually and collectively.

Other nations were far more skeptical. France and the United Kingdom, for example, were wary of potential regulations that might hamper the British-French fleet of supersonic Concorde jet airliners, which had just entered operation in 1969.

Developing countries too were suspicious, viewing environmental initiatives as part of an agenda advanced by wealthy nations that would prevent them from industrializing. In response to calls from industrialized countries to curb pollution, Brazilian delegate Bernardo de Azevedo Brito stated:

I do not believe we are prepared to become new Robinson Crusoes.

These are some of the factors that are increasing zoonosis emergence.

Other factors include:

?? Invasive species that carry microbes into new habitats

?? International travel & commerceThe #coronavirus pandemic highlights the need to address threats to nature.#COVID19 pic.twitter.com/c1daucdkBy

— UN Environment Programme (@UNEP) April 1, 2020

A UN agency for the environment

Largely because of U.S. leadership, industrialized nations agreed to establish and provide initial funding for what is arguably the world’s premier global environmental institution: the United Nations Environment Programme. UNEP catalyzed negotiation of the 1985 Vienna Convention and its follow-on, the 1987 Montreal Protocol, a treaty to restrict production and use of substances that deplete Earth’s protective ozone layer. Today the agency continues to drive international efforts on issues including pollution control, biodiversity conservation and climate change.

John W. McDonald, who was director of economic and social affairs at the U.S. State Department’s Bureau of International Organization Affairs, had been circulating the idea of a new U.N. agency for the environment, and had garnered support from the Nixon administration. But creating a new international environmental institution could only happen with financial support from industrialized countries.

In an address to Congress on Feb. 8, 1972, Nixon proposed creating a US$100 million Environment Fund – close to $600 million in today’s dollars – to support effective international cooperation on environmental problems and create a central coordination point for U.N. activities. Recognizing that the United States was the world’s major polluter, the Nixon administration provided 30% of this sum over the first five years.

Samuel de Palma, left, assistant secretary for International Organization Affairs, presents the State Department’s Superior Honor Award to John W. McDonald in 1972 for his role in creating the U.N. Environment Programme. Also shown: McDonald’s wife Christel McDonald and Christian A. Herter, Jr., deputy assistant secretary of state. Image via the archives of Christel McDonald/The Conversation.

Over the next two decades the United States was the largest single contributor to the fund, which supports UNEP’s work worldwide. By the early 1990s, it was providing $21 million annually – equivalent to about $38 million in today’s dollars.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the rest of article here.

Maria Ivanova, Associate Professor of Global Governance and Director, Center for Governance and Sustainability, John W. McCormack Graduate School of Policy and Global Studies, University of Massachusetts Boston

Bottom line: The history of Earth Day.

![]()

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/3buelym

The first Earth Day in 1972 spurred other countries to support global environmental action. Image via Callista Images/Getty

By Maria Ivanova, University of Massachusetts Boston

The first Earth Day protests, which took place on April 22, 1970 brought 20 million Americans – 10% of the U.S. population at the time – into the streets. Recognizing the power of this growing movement, President Richard Nixon and Congress responded by creating the Environmental Protection Agency and enacting a wave of laws, including the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act and the Endangered Species Act.

But Earth Day’s impact extended far beyond the United States. A cadre of professionals in the U.S. State Department understood that environmental problems didn’t stop at national borders, and set up mechanisms for addressing them jointly with other countries.

For scholars like me who study global governance, the challenge of getting nations to act together is a central issue. In my view, without the first Earth Day, global action against problems like trade in endangered species, stratospheric ozone depletion and climate change would have taken much longer – or might never have happened at all.

An estimated 7,000 demonstrators in Philadelphia on Earth Day, April 22, 1970. Image via AP Photo

Alarms across the world

In 1970 governments around the world were contending with transborder pollution challenges. For example, sulfur and nitrogen oxides emitted from coal-fired power plants in the United Kingdom traveled hundreds of miles on northerly winds, then returned to earth in northern Europe as acid rain, fog and snow. This process was killing lakes and forests in Germany and Sweden.

Realizing that solutions would only be effective through common effort, countries convened the first global conference on the environment in Stockholm from June 5-16, 1972. Representatives of 113 governments attended and adopted the Stockholm Declaration on the Human Environment, which asserts that humans have a fundamental right to an environment that permits a life of dignity and well-being. They also passed a resolution to create a new international environmental institution.

Contrary to its posture today, the United States was an ardent proponent of the conference. The U.S. delegation advanced a series of actions, including a moratorium on commercial whaling, a convention to regulate ocean dumping and the creation of a World Heritage Trust to preserve wilderness areas and scenic natural landmarks.

President Nixon issued a statement when the conference concluded, observing that…

for the first time in history, the nations of the world sat down together to seek better understanding of each other’s environmental problems and to explore opportunities for positive action, individually and collectively.

Other nations were far more skeptical. France and the United Kingdom, for example, were wary of potential regulations that might hamper the British-French fleet of supersonic Concorde jet airliners, which had just entered operation in 1969.

Developing countries too were suspicious, viewing environmental initiatives as part of an agenda advanced by wealthy nations that would prevent them from industrializing. In response to calls from industrialized countries to curb pollution, Brazilian delegate Bernardo de Azevedo Brito stated:

I do not believe we are prepared to become new Robinson Crusoes.

These are some of the factors that are increasing zoonosis emergence.

Other factors include:

?? Invasive species that carry microbes into new habitats

?? International travel & commerceThe #coronavirus pandemic highlights the need to address threats to nature.#COVID19 pic.twitter.com/c1daucdkBy

— UN Environment Programme (@UNEP) April 1, 2020

A UN agency for the environment

Largely because of U.S. leadership, industrialized nations agreed to establish and provide initial funding for what is arguably the world’s premier global environmental institution: the United Nations Environment Programme. UNEP catalyzed negotiation of the 1985 Vienna Convention and its follow-on, the 1987 Montreal Protocol, a treaty to restrict production and use of substances that deplete Earth’s protective ozone layer. Today the agency continues to drive international efforts on issues including pollution control, biodiversity conservation and climate change.

John W. McDonald, who was director of economic and social affairs at the U.S. State Department’s Bureau of International Organization Affairs, had been circulating the idea of a new U.N. agency for the environment, and had garnered support from the Nixon administration. But creating a new international environmental institution could only happen with financial support from industrialized countries.

In an address to Congress on Feb. 8, 1972, Nixon proposed creating a US$100 million Environment Fund – close to $600 million in today’s dollars – to support effective international cooperation on environmental problems and create a central coordination point for U.N. activities. Recognizing that the United States was the world’s major polluter, the Nixon administration provided 30% of this sum over the first five years.

Samuel de Palma, left, assistant secretary for International Organization Affairs, presents the State Department’s Superior Honor Award to John W. McDonald in 1972 for his role in creating the U.N. Environment Programme. Also shown: McDonald’s wife Christel McDonald and Christian A. Herter, Jr., deputy assistant secretary of state. Image via the archives of Christel McDonald/The Conversation.

Over the next two decades the United States was the largest single contributor to the fund, which supports UNEP’s work worldwide. By the early 1990s, it was providing $21 million annually – equivalent to about $38 million in today’s dollars.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the rest of article here.

Maria Ivanova, Associate Professor of Global Governance and Director, Center for Governance and Sustainability, John W. McCormack Graduate School of Policy and Global Studies, University of Massachusetts Boston

Bottom line: The history of Earth Day.

![]()

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/3buelym

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire