The origin of digits in land vertebrates is hotly debated, but a new

study suggests that human hands likely evolved from the fins of

Elpistostege, a fish that lived more than 380 million y

This animation shows what Elpistostege might have looked like when alive, and highlights the close similarities in its pectoral fin skeleton to the bones of our human arm and hand.

Image via Katrina Kenny/ The Conversation.

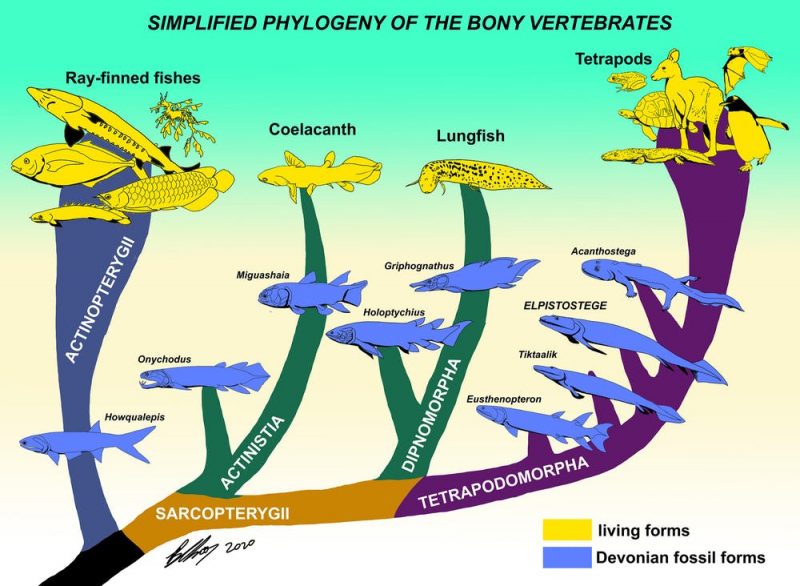

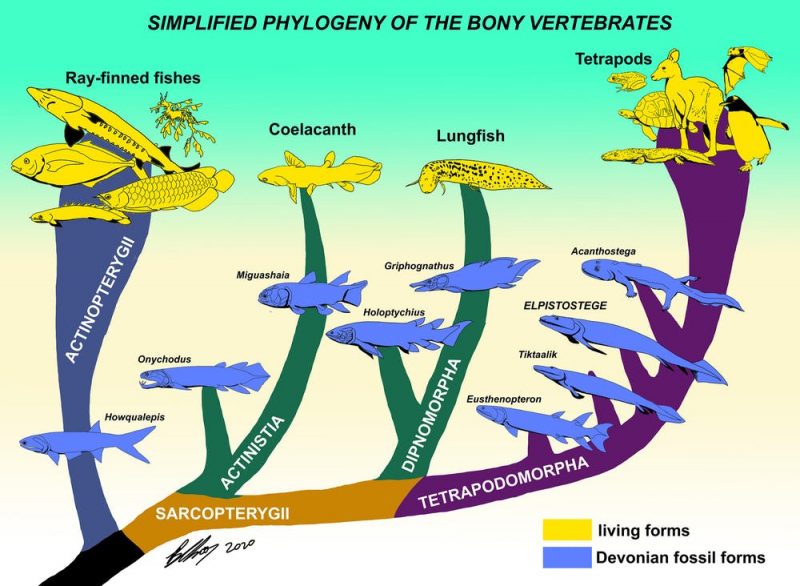

One of the most significant events in the history of life was when fish evolved into tetrapods, crawling out of the water and eventually conquering land. The term tetrapod refers to four-limbed vertebrates, including humans.

To complete this transition, several

anatomical changes were necessary. One of the most important was the

evolution of hands and feet.

Working with researchers from the University of Quebec, in 2010 we discovered the first complete specimen of Elpistostege watsoni. This tetrapod-like fish lived more than 380 million years ago, and belonged to a group called elpistostegalians.

Our research based on this specimen, published today in Nature, suggests human hands likely evolved from the fins of this fish, which we’ll refer to by its genus name, Elpistostege.

Elpistostegalians are an extinct group that

displayed features of both lobe-finned fish and early tetrapods. They

were likely involved in bridging the gap between prehistoric fish and

animals capable of living on land.

Thus, our latest finding offers valuable insight into the evolution of the vertebrate hand.

Elpistostege,

from the Late Devonian period of Canada, is now considered the closest

fish to tetrapods (4-limbed land animals), which includes humans. Image

via Brian Choo/ The Conversation.

The best specimen we’ve ever found

To understand how fish fins became limbs

(arms and legs with digits) through evolution, we studied the fossils of

extinct lobe-finned fishes and early tetrapods.

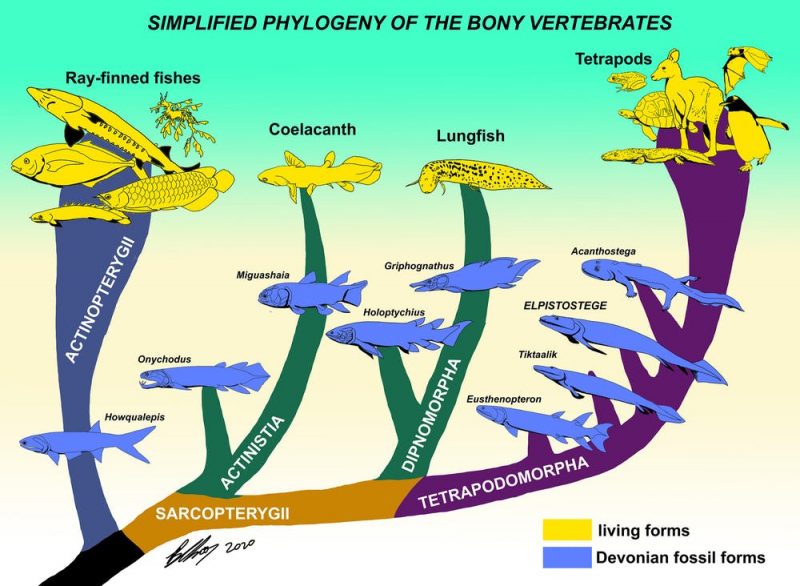

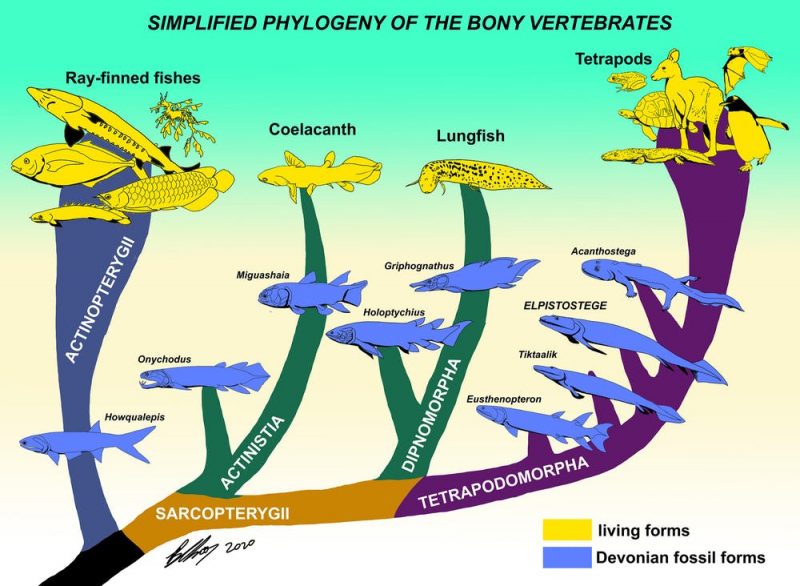

Lobe-fins include bony fishes (Osteichthyes) with robust fins, such as lungfishes and coelacanths.

Elpistostegalians lived between 393–359 million years ago, during the Middle and Upper Devonian times. Our finding of a complete 1.57 meter (5-foot) Elpistostege – uncovered from Miguasha National Park in Quebec, Canada – is the first instance of a complete skeleton of any elpistostegalian fish fossil.

This animation shows what Elpistostege might have looked like when alive, and highlights the close similarities in its pectoral fin skeleton to the bones of our human arm and hand.

Prior to this, the most complete elpistostegalian specimen was a Tiktaalik roseae skeleton found in the Canadian Arctic in 2004, but it was missing the extreme end part of its fin.

When fins became limbs

The origin of digits in land vertebrates is hotly debated.

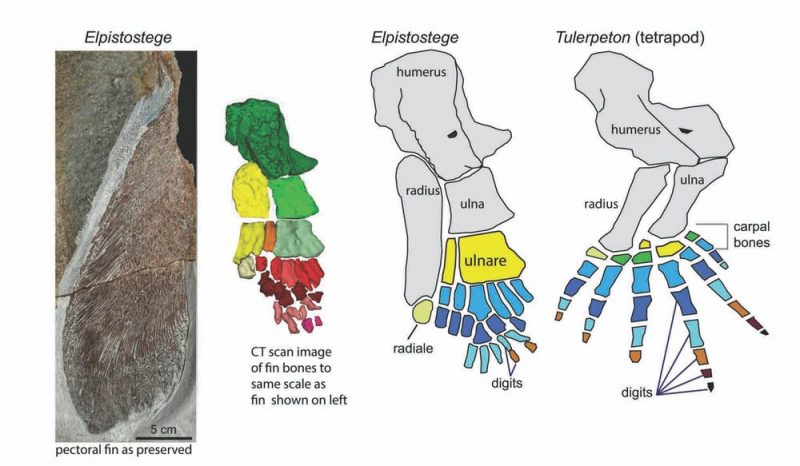

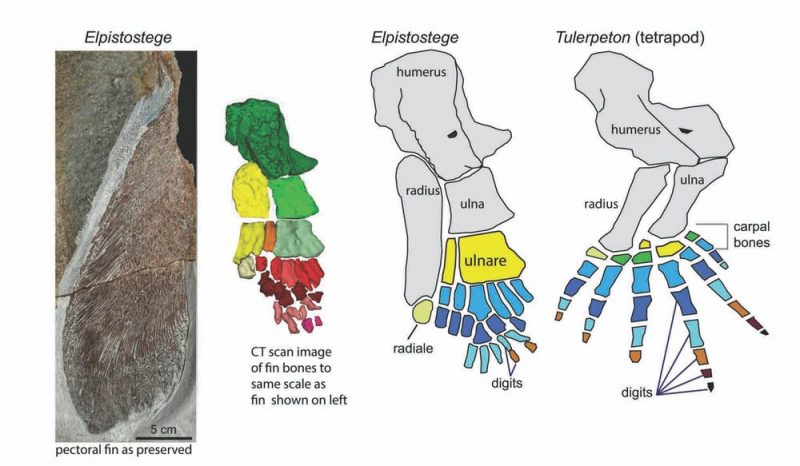

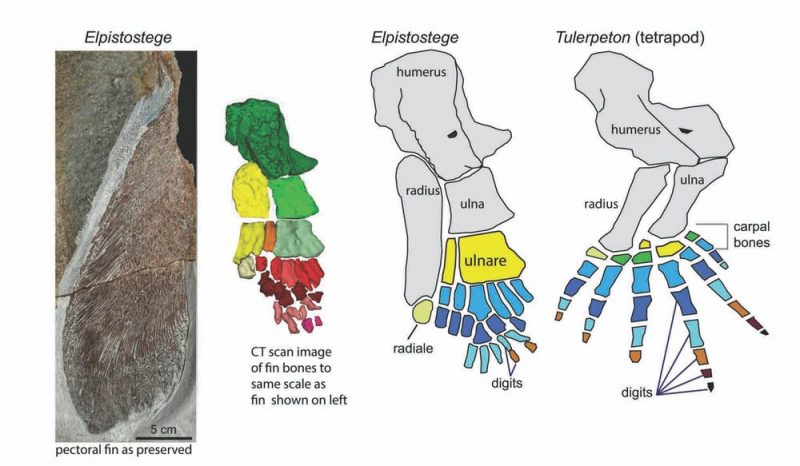

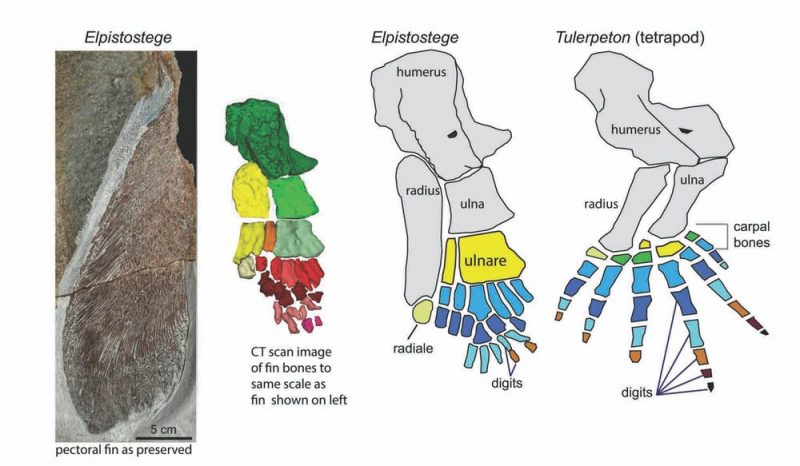

The tiny bones in the tip of the pectoral fins of fishes such as Elpistostege

are called “radial” bones. When radials form a series of rows, like

digits, they are essentially the same as fingers in tetrapods.

The only difference is that, in these

advanced fishes, the digits are still locked within the fin, and not yet

free moving like human fingers.

Our recently uncovered Elpistostege

specimen reveals the presence of a humerus (arm), radius and ulna

(forearm), rows of carpal bones (wrist) and smaller bones organised in

discrete rows.

We believe this is the first evidence of

digit bones found in a fish fin with fin-rays (the bony rays that

support the fin). This suggests the fingers of vertebrates, including of

human hands, first evolved as rows of digit bones in the fins of

elpistostegalian fishes.

The pectoral fin of Elpistostege

shows the short rows of aligned digits in the fin, an intermediate

stage between fishes and land animals such as the early tetrapod Tulerpeton. Image via The Conversation.

What’s the evolutionary advantage?

From an evolutionary perspective, rows of

digit bones in prehistoric fish fins would have provided flexibility for

the fin to more effectively bear weight.

This could have been useful when Elpistostege

was either plodding along in the shallows, or trying to move out of

water onto land. Eventually, the increased use of such fins would have

lead to the loss of fin-rays and the emergence of digits in rows,

forming a larger surface area for the limb to grip the land surface.

Our specimen shows many features not known

before, and will form the basis of a series of future papers describing

in detail its skull, and other aspects of its body skeleton.

Elpistostege blurs the line

between fish and vertebrates capable of living on land. It’s not

necessarily our ancestor, but it’s now the closest example we have of a

“transitional fossil”, closing the gap between fish and tetrapods.

Our new specimen of Elpistostege watsoni measures 5.15 feet (1.57 meters) long from its snout to the tip of its tail. Image via Richard Cloutier/ UQAR/ The Conversation.

The full picture

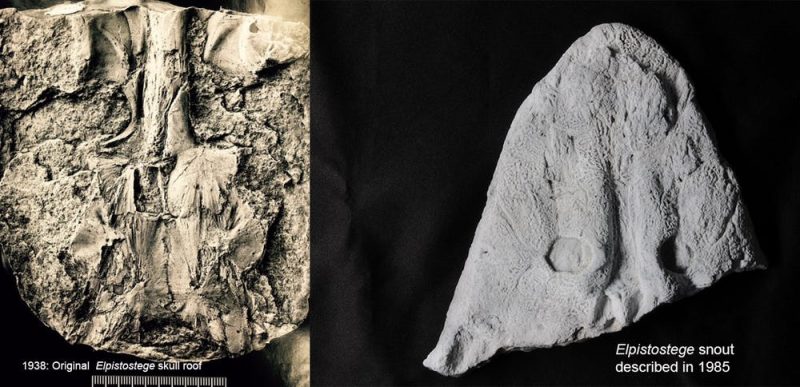

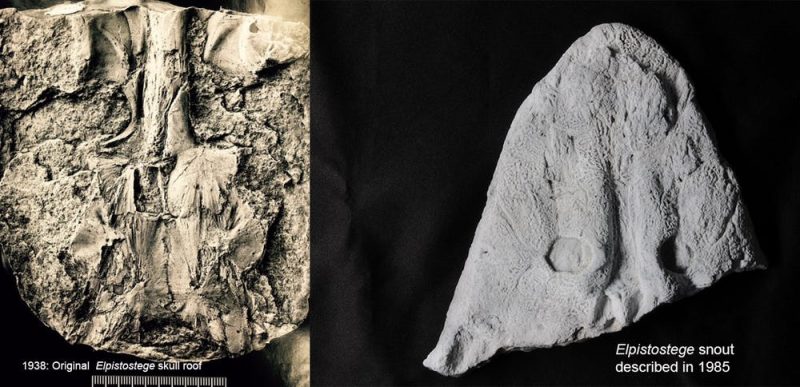

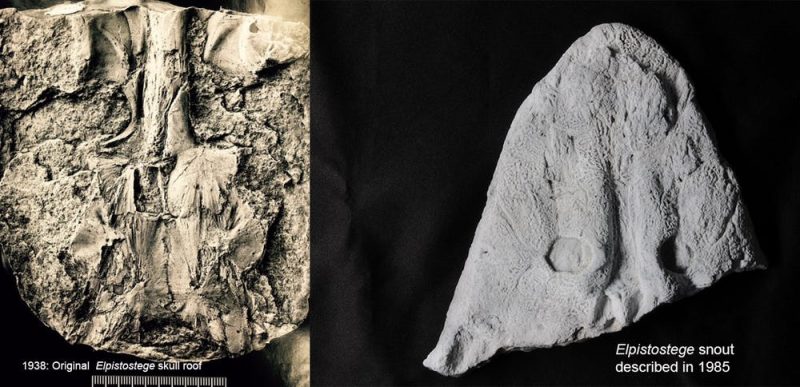

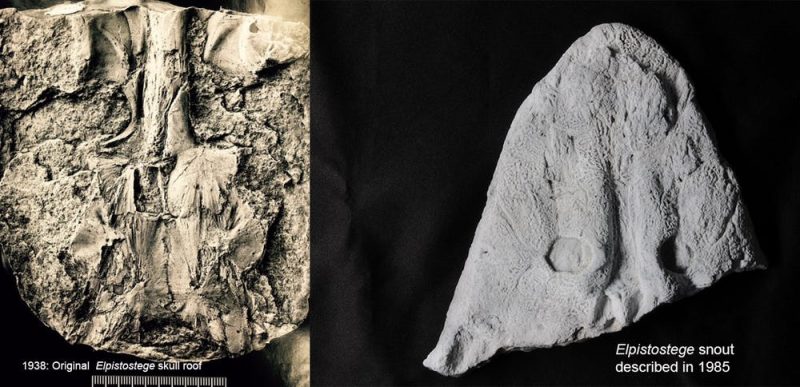

The first Elpistostege fossil, a

skull fragment, was found in the late 1930s. It was thought to belong to

an early amphibian. In the mid 1980s the front half of the skull was

found, and was confirmed to be an advanced lobe-finned fish.

The original finds of the Elpistostege

skull roof (left) and front half of the skull. The new specimen

confirms these all belong to the one species. Image via Richard

Cloutier/ UQAR/ The Conversation.

Our new, complete specimen was discovered in the fossil-rich cliffs of the Miguasha National Park,

a UNESCO World Heritage site in Eastern Canada. Miguasha is considered

one of the best sites to study fish fossils from the Devonian period

(known as the “Age of Fish”), as it contains a very large number of

lobe-finned fish fossils, in an exceptional state of preservation.

John Long, Strategic Professor in Palaeontology, Flinders University and Richard Cloutier, Professor of Evolutionary Biology, Université du Québec à Rimouski (UQAR).

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Bottom line: A new study suggests that human hands likely evolved from the fins of Elpistostege, a fish that lived more than 380 million years ago.

The origin of digits in land vertebrates is hotly debated, but a new

study suggests that human hands likely evolved from the fins of

Elpistostege, a fish that lived more than 380 million y

This animation shows what Elpistostege might have looked like when alive, and highlights the close similarities in its pectoral fin skeleton to the bones of our human arm and hand.

Image via Katrina Kenny/ The Conversation.

One of the most significant events in the history of life was when fish evolved into tetrapods, crawling out of the water and eventually conquering land. The term tetrapod refers to four-limbed vertebrates, including humans.

To complete this transition, several

anatomical changes were necessary. One of the most important was the

evolution of hands and feet.

Working with researchers from the University of Quebec, in 2010 we discovered the first complete specimen of Elpistostege watsoni. This tetrapod-like fish lived more than 380 million years ago, and belonged to a group called elpistostegalians.

Our research based on this specimen, published today in Nature, suggests human hands likely evolved from the fins of this fish, which we’ll refer to by its genus name, Elpistostege.

Elpistostegalians are an extinct group that

displayed features of both lobe-finned fish and early tetrapods. They

were likely involved in bridging the gap between prehistoric fish and

animals capable of living on land.

Thus, our latest finding offers valuable insight into the evolution of the vertebrate hand.

Elpistostege,

from the Late Devonian period of Canada, is now considered the closest

fish to tetrapods (4-limbed land animals), which includes humans. Image

via Brian Choo/ The Conversation.

The best specimen we’ve ever found

To understand how fish fins became limbs

(arms and legs with digits) through evolution, we studied the fossils of

extinct lobe-finned fishes and early tetrapods.

Lobe-fins include bony fishes (Osteichthyes) with robust fins, such as lungfishes and coelacanths.

Elpistostegalians lived between 393–359 million years ago, during the Middle and Upper Devonian times. Our finding of a complete 1.57 meter (5-foot) Elpistostege – uncovered from Miguasha National Park in Quebec, Canada – is the first instance of a complete skeleton of any elpistostegalian fish fossil.

This animation shows what Elpistostege might have looked like when alive, and highlights the close similarities in its pectoral fin skeleton to the bones of our human arm and hand.

Prior to this, the most complete elpistostegalian specimen was a Tiktaalik roseae skeleton found in the Canadian Arctic in 2004, but it was missing the extreme end part of its fin.

When fins became limbs

The origin of digits in land vertebrates is hotly debated.

The tiny bones in the tip of the pectoral fins of fishes such as Elpistostege

are called “radial” bones. When radials form a series of rows, like

digits, they are essentially the same as fingers in tetrapods.

The only difference is that, in these

advanced fishes, the digits are still locked within the fin, and not yet

free moving like human fingers.

Our recently uncovered Elpistostege

specimen reveals the presence of a humerus (arm), radius and ulna

(forearm), rows of carpal bones (wrist) and smaller bones organised in

discrete rows.

We believe this is the first evidence of

digit bones found in a fish fin with fin-rays (the bony rays that

support the fin). This suggests the fingers of vertebrates, including of

human hands, first evolved as rows of digit bones in the fins of

elpistostegalian fishes.

The pectoral fin of Elpistostege

shows the short rows of aligned digits in the fin, an intermediate

stage between fishes and land animals such as the early tetrapod Tulerpeton. Image via The Conversation.

What’s the evolutionary advantage?

From an evolutionary perspective, rows of

digit bones in prehistoric fish fins would have provided flexibility for

the fin to more effectively bear weight.

This could have been useful when Elpistostege

was either plodding along in the shallows, or trying to move out of

water onto land. Eventually, the increased use of such fins would have

lead to the loss of fin-rays and the emergence of digits in rows,

forming a larger surface area for the limb to grip the land surface.

Our specimen shows many features not known

before, and will form the basis of a series of future papers describing

in detail its skull, and other aspects of its body skeleton.

Elpistostege blurs the line

between fish and vertebrates capable of living on land. It’s not

necessarily our ancestor, but it’s now the closest example we have of a

“transitional fossil”, closing the gap between fish and tetrapods.

Our new specimen of Elpistostege watsoni measures 5.15 feet (1.57 meters) long from its snout to the tip of its tail. Image via Richard Cloutier/ UQAR/ The Conversation.

The full picture

The first Elpistostege fossil, a

skull fragment, was found in the late 1930s. It was thought to belong to

an early amphibian. In the mid 1980s the front half of the skull was

found, and was confirmed to be an advanced lobe-finned fish.

The original finds of the Elpistostege

skull roof (left) and front half of the skull. The new specimen

confirms these all belong to the one species. Image via Richard

Cloutier/ UQAR/ The Conversation.

Our new, complete specimen was discovered in the fossil-rich cliffs of the Miguasha National Park,

a UNESCO World Heritage site in Eastern Canada. Miguasha is considered

one of the best sites to study fish fossils from the Devonian period

(known as the “Age of Fish”), as it contains a very large number of

lobe-finned fish fossils, in an exceptional state of preservation.

John Long, Strategic Professor in Palaeontology, Flinders University and Richard Cloutier, Professor of Evolutionary Biology, Université du Québec à Rimouski (UQAR).

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Bottom line: A new study suggests that human hands likely evolved from the fins of Elpistostege, a fish that lived more than 380 million years ago.

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire